| Return to Index |

|

Paper 58 A Selection of Balls from 1808Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 22nd July 2022, Last Changed - 28th November 2023]This paper continues the theme of studying a selection of historical balls that were all held in the same calendar year, this time the year is 1808. The events have been selected based on the quality of information that has been recorded about them; most historical events offer no hope of reconstruction, in a few cases the newspapers recorded sufficient information that we might at least reconstruct a partial play-list of tunes and dances that were enjoyed. It's those fragments of information that we will explore further in this paper. There is no connecting theme to group the events, they're just a selection of balls held by the British aristocracy and gentry in the year 1808. There are so many references worth studying from 1808 that we have split the information into two separate papers; you are currently reading the first paper, the second is available here. The tunes and dances that we'll consider further in this paper are:

Figure 1. Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge c.1808. The Duke was the guest of honour at Mrs Robinson's two balls. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

Figure 1. Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge c.1808. The Duke was the guest of honour at Mrs Robinson's two balls. Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

Two balls held by the Hon. Mrs RobinsonWe'll begin by considering two balls held by the honourable Mrs Robinson within a few days of each other in April 1808. The Morning Post newspaper for the 2nd of April 1808 printed of the first (with dance references in bold): A few days later the Morning Post newspaper for the 7th of April 1808 recorded (once again with dance references highlighted in bold):On Thursday evening, in Privy Gardens, the above Lady gave a magnificent Ball and Supper; the preparations corresponded with her well-known taste and elegance. There were no less than six rooms, each more superbly furnished than the other, thrown open about ten o'clock. The effect was rendered complete by the introduction of rare exotics and sweet-smelling shrubs. About half-past ten the merry dance of[a long list of notables followed]The Ridicule,was led off by the Honourable Mr Townshend and Lady Frances Herries. Among the couples there were the following: Lord James Murray ... Miss Finch Hatton, Lord M. Taylor ... Lady M. Townshend, Mr Montague ... Lady G. Cecil. The above fashionable Lady gave her second grand Ball on Tuesday evening; it decidedly ranked among the most elegant the season has yet produced. A suite of no less than seven rooms were thrown open about ten o'clock; about eleven the dancing commenced. The Ball was opened by Lord Clive and Lady D. Herbert, to the favourite tune of[a long list of notables followed]La Belle Laitiere.Among the couples were:- Marquis of Tweedale ... Lady Fitzroy, Lord Palmerstone ... Lady F. Herries, Lord Forbes ... Miss Cornwall, Mr Montagu ... Miss Thompson. The two events were held five days apart in April 1808. Most of the named guests (they're cropped from the lists above) were different across the two events, this suggests that attendance was limited by the size of the venue and that Mrs Robinson's social circle were distributed across the two events. The hostess was Catherine Robinson (1749-1834), she was a daughter of James Harris (1709-1780) who had married Hon Frederick Robinson (1746-1792) in 1785. She had no children of her own and so, a little unusually, other honoured guests were given the opportunity to lead off the first dance at each of the events. Both events were presumably held at the hostesses home in the Privy Gardens area of Whitehall, we've written of two 1803 balls held there by Mrs Robinson in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. Two tunes have been named as having led off the dancing at these events, we'll study them shortly. The guest of honour at both of Mrs Robinson's balls was the Duke of Cambridge, brother to the Prince of Wales (see Figure 1).

The Duchess of York's Fete at Oatlands

Figure 2. The Duchess of York c.1808. Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. The Duchess of York c.1808. Image courtesy of the Wikimedia Commons.

On Saturday se'nnight a grand Fete was given at Oatlands in honour of her Royal Highness's Birth-day. The preparations were unusually costly. The King, Queen, the Princesses Augusta, Elizabeth, Mary, Sophia, and Amelia; the Prince of Wales; Dukes of York, Kent, Clarence, Sussex, and Cumberland, were present. Indisposition only prevented the Duke of Cambridge from attending. Their Majesties and the Princesses arrived from two o'clock. The Duke and Duchess of York were in waiting to receive their illustrious relatives; from the bottom of the flight of steps leading into the great hall, the Duke escorted the Queen to the grand saloon. After viewing and admiring the improvements made on the lawns, &c. the Royal Party partook of a most sumptuous banquet, served up in a costly service of silver gilt plate. During the time of dinner, the Duke of York's band, in full uniform, played under the veranda on the green. The King wore the Windsor uniform. The Queen and the Princesses were dressed in plain white. His Majesty, it was remarked, looked uncommonly well, and possessed his usual flow of spirits. Their Majesties and the Princesses departed about eight o'clock, escorted, as usual by a party of dragoons. About nine o'clock the fun and merriment took place. The Duchess having ordered the Park gates to be thrown open, the populace (principally composed of the neighbouring peasantry) rushed in, and made the best of their way to the lower part of the house, wherein a vast number of tables were set out with hot fowls, veal, ham, beef, and mutton; together with abundance of strong ale and porter, all arranged with perfect order. After partaking of this good cheer, amagnum bonum(about six quarts) of excellent punch was placed upon each table. The lively notes of the fiddler aroused the lads and lasses about nine o'clock. The tables were instantaneously deserted for the library, where the Duchess led off the first dance called The Labyrinth, with the Hon. Colonel Upton. Her Highness never appeared to better advantage; she is improved in health, and is grown ratherembonpointthan otherwise. The very awkward manner in which the country people paid their respects to the Heir apparent (in their going down the dance) excited the risibility of the Royal Party to an extreme degree. It was not until two o'clock in the morning that the music ceased, and then the company retired. This event was held at Oatlands by and for the Duchess of York, we've written of a similar 1799 event held at Oatlands in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. We read of our event that the Duchess of York led off a dance named The Labyrinth, we'll read more of it shortly, and that the local peasantry had been allowed to attend. We're presented with the lovely anecdote of the awkward fashion in which the country people paid their respects to the Duke of York as they passed him in the dance, they evidently attempted to mimic the courtly conventions of the nobility, causing much merriment for those who observed. We're informed that a good deal of alcohol had already been imbibed by that point, presumably the dancing was conducted with good cheer. Most of the Royal Family had already left before the dancing began, it was just the Duke and Duchess of York who danced, their immediate retinue, and the local populace.

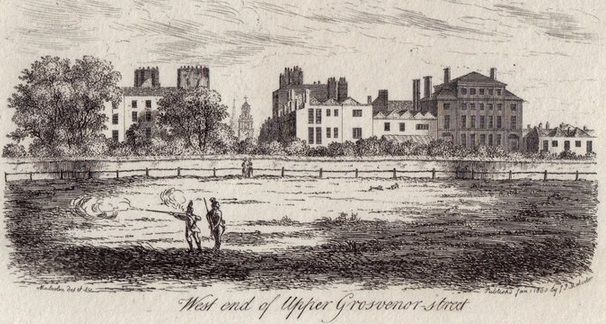

The Hon. Mrs Thomas Knox's Grand Ball and Supper Figure 3. West end of Upper Grosvenor Street, 1808.

Figure 3. West end of Upper Grosvenor Street, 1808.

Three different newspapers all recorded the same event in May 1808. The hostess was the Hon. Diana Knox (1764-1839), the wife of The Honourable Thomas Knox (1754-1840). They had been married back in 1785, their fourth son would have recently turned 18 at the date of the ball. The ball was held in their home on Upper Grosvenor Street, a general view of which can be seen in Figure 3. The Morning Herald for the 19th of May 1808 reported (with dance references in bold): Mrs Knox's Ball and Supper, on Tuesday evening, in Upper Grosvenor-street, was attended by upwards of 400 persons of the first distinction and fashion. The Ball was opened a little before twelve o'clock, by the Hon. Mr. Eden and Lady Sarah Spencer, to the admired Air of[a long list of fashionables followed]Catalani's Waltz, followed by nearly 30 couple in two sets; the Supper was announced soon after two; dancing recommenced at half past three and continued tell seven. Among other distinguished Fashionable we noticed: His Highness the Duke of Gloucester, Duchesses Marlborough, Northumberland, Grafton, and Athol; ... The British Press newspaper for the same day, 19th of May 1808, offered a slightly fuller account with some differing details (and with dance references emphasised in bold): The Hon. Mrs. Knox gave a grand ball and supper on Tuesday night at her elegant house in Upper Grosvenor-street. The preparations for the evening displayed the greatest magnificence. The great hall and staircase were lighted by Roman and patent lamps, fixed upon bronze figures. Five rooms on the ground-floor were appropriated for supper. In the front parlour there was a horse-shoe table, set for 90 persons. The other rooms were arranged in the most effectual manner for the accommodation of the guests. The supper was hot, and served on services of the finest plate; nor was the humble buttock of beef the least admired of the viands, Green peas, new potatoes, and strawberries, were in great profusion, as was every other delicacy of the season. The grand drawing rooms were thrown open. They are hung with embossed pink paper, with a rich gold tissue open border, surrounded with gold mouldings, and lighted by Grecian lamps; the second room nearly to correspond. The front drawing-room was appropriated for dancing; a diamond-cut glass chandelier was suspended from the ceiling; opposite the chimney is a large glass, near ten feet high, in a rich gilt frame; a temporary drapery was put up along the windows, decorated with garlands of flowers. The floor was tastefully chalked in devices, with the shamrock at each angle. Mr Gow's full band was placed in this room. At eleven o'clock the ball was opened by Earl Kinnoul and Lady Sarah Spencer, to the tune of[a list of fashionables followed]The Fairy Dance; the second dance,Miss Johnstone, was led off by the Hon. Mr Eden and Lady Perry; they then dancedTekeli; dancing was kept up with great spirit till past two. At four o'clock the company returned to the ball-room, when dancing was resumed with great spirit. It was six o'clock before they departed, highly gratified with their splendid entertainment. Amongst the company were: His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester, ... The Morning Post that same day, 19th of May 1808, offered yet another account. This final narrative combines details of each of the other two (with dance references highlighted in bold): Given on Tuesday evening, in Upper Grosvenor-street, was attended by 40 of the fashionable world. This elegant Lady's magnificent residence was fitted up for the occasion with an appropriate taste, and illuminated in a style of corresponding splendour. There was nothing novel in the interior decorations but what we have already detailed. Owing to the lateness of the hour when the company arrived, the dancing did not commence until half-past eleven o'clock; the first dance was the[The list of attendees continued]Fairy Dance, led off by the Hon. Mr Eden and Lady E. Spencer; next followed: Several important details emerge from across these accounts. We know that the music was provided by the popular Gow band, that some of the rooms were too hot to dance in, that dancing began somewhere between 11 and 12 at night, that around 30 couples danced across two sets of 15 couples, and that four different tunes have been named as being danced. We also have much of the menu of the supper that was served. The four tunes names were The Fairy Dance, Miss Johnstone, Tekeli and Catalani's Waltz; we've studied three of these tunes in previous papers, we will return to study the fourth shortly. It's fascinating to compare the differences and similarities between these three accounts. It's unusual to find independent descriptions with this level of detail. Some of the reports were evidently wrong with respect to some of their minor details, it's no longer possible to discern which are the most reliable but the disparate accounts are largely compatible with each other. It's reasonable to assume that the same will be true of other ball narratives at a similar date, the published descriptions may be erroneous in small matters but they are probably of sufficient accuracy for our purposes. Perhaps the writer confused the identity of the leading couple, or named one tune as having been danced first where actually it was another... such minor errors are of little significance overall. We've studied another ball of 1809 which also enjoyed multiple descriptions in the press, our findings were similar then too; we'll encounter a further such example shortly below.

Two balls held by the Countess of ShaftesburyLady Shaftesbury (see Figure 4) was born Barbara Webb, she was the daughter of Sir John Webb. She married Anthony Ashley-Cooper (1761-1811), the Earl of Shaftesbury in 1786. Their daughter Lady Barbara Ashley-Cooper (1788-1844) would have turned 20 at around the date at which her parents hosted two balls in 1808, it's likely that the balls were held as her introduction to society. The two balls were held within around two weeks of each other in the summer.  Figure 4. An image believed to be of Barbara, Countess of Shaftesbury.

Figure 4. An image believed to be of Barbara, Countess of Shaftesbury.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 23rd of June 1808 recorded of the first (with dance references highlighted in bold): The Morning Post newspaper for the 8th of July 1808 recorded of the second ball (with dance references highlighted in bold):All the World of Fashion were assembled together on Tuesday night, at her Ladyship's residence in Portland-place. This mansion is extremely well adapted for magnificent fetes. The apartments are numerous, and of lofty proportions. Each room was superbly illuminated with Grecian lamps, at an early hour. The visitors not arriving until after 11 o'clock, the dancing did not commence until 12, when a nouvelle kind of cotillion, called a French Country Dance, was led off by the Hon. Keppel Craven, and Lady Barbara Ashley Cowper, the fair daughter of the Countess of Shaftesbury. Colonel Mercer, followed with Miss Johnstone. Four couple made up the set, the dance attracted great attention, and was warmly applauded even by clapping of hands. The usual English country dances which followed were preceded by two new ones, both composed by a Lady of distinction; one was the[a list of fashionables attending followed]The Runaway,and the name of the other we could not learn. Among the couples that stood up were, Given on Wednesday Evening, was attended by the same degree of eclat as the one preceding. The company were not so numerous, owing, no doubt, to the cards of invitation not having been in general circulation until the morning of the day on which the Entertainment was given. The splendid arrangements which distinguished the first Ball were conspicuous on this occasion. It was half past eleven o'clock, ere the dancing commenced. Lady Barbara-Ashley-Cowper, Miss Johnstone, and two Gentlemen, led off with the French Cotillions, now so much the rage. Country dances commenced about one. The following were among the couples:[a list of fashionables]

These two events both commenced with a new type of Cotillion or French Country Dance. We'll consider what that dance might have been below, it's a fascinating detail however. We're told that this dance at the first ball attracted applause from the audience We're also informed that several Country Dances were enjoyed, notably The Runaway which we'll investigate further shortly. The second ball is reported to have closed with the dancing of reels and strathspeys that were still being danced by the young Lady Barbara until around 7.00am. We've investigated the concept of reels and strathspeys in previous papers, you might like to follow the link to read more.

The Duchess of Bolton's BallThe Duchess of Bolton was Katharine Powlett (1736-1809), she was the second wife of Admiral Harry Powlett (1720-1794) the 6th Duke of Bolton. She hosted a ball at her home in Grosvenor Square (a general view of which can be seen in Figure 5) in 1808 that chanced to be described by two independent accounts in the newspapers. The Daily Advertiser for the 13th of July 1808 wrote (with dance references emphasised in bold):  Figure 5. Grosvenor Square, 1800.

Figure 5. Grosvenor Square, 1800.

The Duchess of Bolton gave a Grand Ball and Supper on Monday evening at her elegant Mansion in Grosvenor-square. Near 300 distinguished Fashionables were present. The preparations on the occasion were in the most superb and elegant manner. The principal drawing-room was fitted up with great taste for dancing. The floor was beautifully chalked; in the centre were her Grace's crest, coronet, and arms; at each corner were vases with flowers, with trophies of war, dancing figures, &c. with a rich Vandyke border; round the room were a profusion of the choicest flowers; from the ceiling were suspended three most costly diamond-cut lustres, side lights, &c. A little before eleven o'clock the Ball was opened by Miss Parry and the Marquis of Tweedale, to the favourite Air of[a list of fashionables followed]Madame Catalani's Waltz.The second dance was led off by the Marquis of Hartington and Lady Louisa Vane to the tune ofthe Runaway,followed by nearly [30?] couple in two sets. The supper, which consisted of all sorts of rich soups, and every delicacy of the season, was announced soon after three o'clock; it was prepared in three rooms on the ground floor; the principal dining parlour, back dinning parlour, and library, where covers were laid for 130. The formal apartment was set apart for the Prince of Wales and a Party who were expected, but were prevented in consequence of His Royal Highness having had the misfortune to sprain his ancle a few days since. Dancing was resumed at half-past four, and continued till nearly eight. The balcony facing the square was tastefully illuminated with variegated lamps. Among the company we noticed: His Royal Highness the Duke of Cumberland, His Royal Highness the Duke of Gloucester, ... The two ladies named as having led off dances are Miss Parry and Lady Louisa Vane. I'm uncertain as to the identity of Miss Parry, I note that the Duchess's mother in law was a member of the Parry family, Miss Parry was presumably a relative. Whereas Lady Louisa Vane (1791-1821) was the Duchess's own grand daughter, it's a little surprising that she led off the second dance rather than the first. The Morning Post newspaper for the 13th of July 1808 wrote of the same event (once again with dance references emphasised in bold): On Monday evening her Grace gave a magnificent ball and supper, at her noble Mansion in Grosvenor-square. The company exceeded two hundred persons, comprising all the rank and fashion that remained in town. The interior decorations corresponded with the well known taste of the Hostess, but then nothing very new was displayed. There were variegated lamps, hung in simple festoons, suspended from balcony windows, which had a pretty effect on the outside of the house. The company beginning to arrive about eleven o'clock, the dancing commenced soon after with[a list of fashionables followed]Prime of Life,a new dance composed by a Lady of distinction; it was much admired. The eldest daughter of the Earl of Darlington led off with the Marquis of Hartington. Fifteen couple followed: among whom were:

This second description names two different tunes as having been danced, it also identifies the leading dancers as being the same couple who were reported to have led the second dance in the Daily Advertiser ( Once again we've observed that where multiple independent descriptions of a ball exist the specific details may vary. There can be little doubt that they describe the same event and that they are generally compatible, but the respective correspondents had a different memory of who led off the dance and which tune they danced to. The correspondents haven't simply made up information about the Ball, they seem rather to have unreliably recalled some of the details that were shared. Exactly who these correspondents were is a matter of speculation, I suspect they could have been minor guests who sought to make a little money by selling details to the newspapers and perhaps also tunes to the music shops. It seems unlikely that a hostess would invite a newspaper reporter to her event deliberately.

The Ridicule / La RidiculeAbout half-past ten the merry dance of The Ridicule was led off by the Honourable Mr Townshend and Lady Frances Herries.(Hon. Mrs Robinson's first ball)

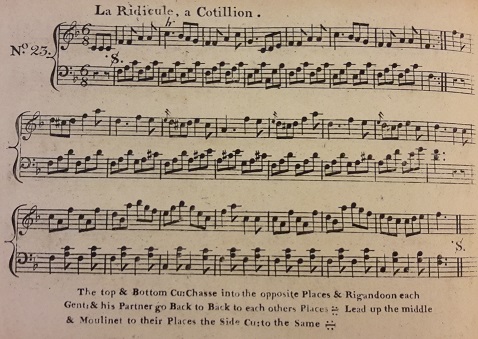

Two tunes or dances circulated around the years 1807 and 1808 under the name  Figure 6. La Ridicule from William Campbell's c.1807 22nd Book. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 6. La Ridicule from William Campbell's c.1807 22nd Book. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The first candidate is a cotillion dance variously named as either

The  Figure 7. The Ridicule from Nathaniel Gow's c.1807 Countess of Dalhousie's Strathspey

Figure 7. The Ridicule from Nathaniel Gow's c.1807 Countess of Dalhousie's Strathspey

The second dance named This all leaves us with a conundrum. Why were two completely different dances circulating under the same name at around the same date? They're not just different tunes under the same name, something not especially unusual, but completely different dance formats. We can only speculate as to a reason. My suspicion is that the Cotillion dance may have emerged first, it's certainly the more unusual of the two dances; one can almost imagine Nathaniel Gow hearing about The Ridicule as becoming popular, assuming the popular tune must have been the unrelated composition by Mrs Robertson, then hurrying that into print and promoting her tune further within the repertoire of the Gow band. However it came to be, both dance tunes were widely published in London approximately concurrently, both must surely have been being danced. Either could have been featured at Mrs Robinson's first ball of 1808.

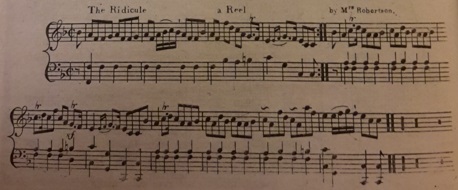

La Belle LaitiereThe Ball was opened by Lord Clive and Lady D. Herbert, to the favourite tune of La Belle Laitiere.(Hon. Mrs Robinson's second ball) The next tune to be named across one of our 1808 balls goes by the name La Belle Laitiere. It's a tune that we have written about before, albeit under a very different context.  Figure 8. The first 8 bars of The Shawl Dance from Steibelt's 1805 La Belle Laitiere (above) and of La Belle Laitiere from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (below).

Figure 8. The first 8 bars of The Shawl Dance from Steibelt's 1805 La Belle Laitiere (above) and of La Belle Laitiere from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (below).

Daniel Steibelt (1765-1823) was the composer of a successful 1805 ballet named La Belle Laitiere, or Blanche Reine de Castille. This ballet was the source of our country dancing tune of the same name. The ballet was performed at the King's Theatre Opera House to great acclaim; the Monthly Mirror magazine in 1805 wrote of it that:

Parisot's shawl dance took on a life of it's own, other performers would go on to perform it on stage elsewhere around the country and the associated score was financially valuable. The music seller Robert Birchall paid £100 to acquire the rights to the ballet (according to the an 1812 writ he issued related to the copyright of the tune that we'll return to in a moment). A country dancing tune circulated from 1805 named La Belle Laitiere, it was inspired by Steibelt's music for Parisot's shawl dance. Several references to the tune being used for social dancing survive from 1805; for example the Morning Post newspaper (27th of July 1805) reported of the Stoke Park Fete that The dance enjoyed at the Robinson ball of 1808 was presumably the tune published by Wheatstone. This tune (or one of the same name) was also engraved on a barrel organ that was advertised for sale in 1808 (Coventry Herald, 9th of December 1808). We've animated a suggested arrangement of the c.1806 version of the dance by Wheatstone & Voigt.

The Labyrinththe Duchess led off the first dance called The Labyrinth, with the Hon. Colonel Upton(Duchess of York's Fete) Our next tune was featured at the Duchess of York's Fete in 1808, we're informed that the dancing opened with a tune named The Labyrinth. This tune is readily identified as it was widely published in London around the year 1808. I've no insight into the composer of the tune but it became known around the year 1807.  Figure 9. The Labyrinth from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (above) and the 1806 Pandean Minstrels in Performance at Vaux-Hall (below). Lower image is courtesy of The V&A.

Figure 9. The Labyrinth from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (above) and the 1806 Pandean Minstrels in Performance at Vaux-Hall (below). Lower image is courtesy of The V&A.

It was danced at several society events from 1807; examples include the Master of the Ceremonies Ball in Ramsgate (Morning Post, 26th of September 1807) and Mr Raikes's Ball of 1808 (Morning Post, 11th of January 1808) where The tune itself was readily available. Most publications of the tune were largely the same, the bass line and repeat markers vary across the publications, as do the suggested dance figures but the tune itself is consistent. The precise sequence of publication is unknown but examples include: Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 5th Number, Goulding's c.1807 9th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1807 2nd Book, Monzani's c.1808 6th Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (see Figure 9), Clementi's c.1808 5th Number, William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book, Kelly's c.1808 New Country Dances for the Year 1808, Dale's c.1808 11th Number, Hime's c.1808 1st Number, Davie's c.1808 18th Number, Cahusac's c.1809 24 Country Dances for the Year 1809 and James Platts's c.1809 8th Number. It was also named in both Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ballroom.

Of those publications the one issued c.1807 by Charles Wheatstone is a little interesting for adding the annotation We've animated a suggested arrangement of Button & Whitaker's c.1808 version (see Figure 9), of Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 version and of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1807 version.

As an aside, the dancing master Thomas Wilson also created a country dancing figure that he namedThe Labyrinthfor the 1811 editions of his An Analysis of Country Dancing publication. It's possible, though I suspect unlikely, that he named his figure for this tune and intended them to be danced together. I suspect however that this was merely a coincidental use of the same name. Nonetheless, modern dancers might like to dance Wilson'sLabyrinthfigure as part of their arrangements for our The Labyrinth tune. For futher references to the tune, see also: Labyrinth (1) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

French Country Dances / Cotillionsthe dancing did not commence until 12, when a nouvelle kind of cotillion, called a French Country Dance, was led off by the Hon. Keppel Craven, and Lady Barbara Ashley Cowper, the fair daughter of the Countess of Shaftesbury. Colonel Mercer, followed with Miss Johnstone. Four couple made up the set, the dance attracted great attention, and was warmly applauded even by clapping of hands.(Countess of Shaftesbury's first ball) Lady Barbara-Ashley-Cowper, Miss Johnstone, and two Gentlemen, led off with the French Cotillions, now so much the rage(Countess of Shaftesbury's second ball)

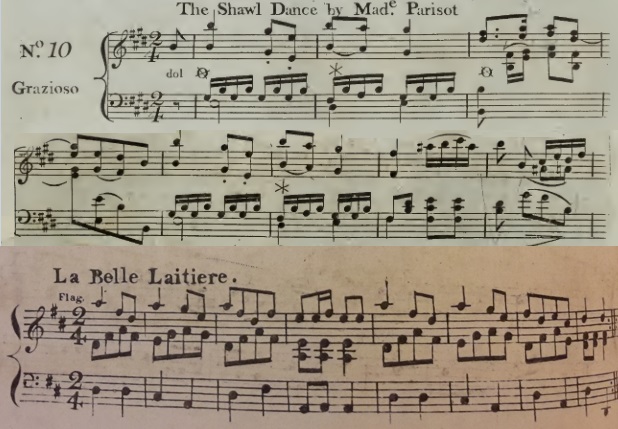

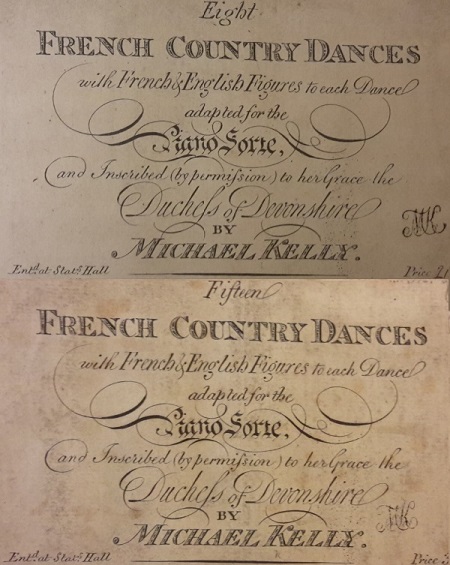

The two Shaftesbury balls of mid 1808 both began with dances variously described as  Figure 10. Two collections of French Country Dances issued by Michael Kelly c.1803

Figure 10. Two collections of French Country Dances issued by Michael Kelly c.1803

The The Cotillion dance declined in popularity across the 1790s however, it had largely fallen from favour by around 1800. It remained known of course, we've already investigated the La Ridicule Cotillion dance of 1807/1808 within this paper, that's an example of a specific Cotillion dance that was still being danced at the date of our balls.

One of the newspapers referred to the dancing of a

Dances referred to as

Our correspondents writing about the two Shaftesbury balls of 1808 seem not to have been dance specialists. Whoever wrote about the first ball didn't understand the term It's worth questioning whether the same specific dance was performed at both Shaftesbury events, or whether the two reports describe two different dances in the same style. The first event was held on Tuesday the 21st of June 1808, the second on Wednesday the 6th of July 1808, approximately two weeks later. The first was clearly a rehearsed performance, the audience were described as having applauded the performers at the conclusion of the dance; it's less clear that the second event also featured a performance. Two of the eight performers at the first ball are also named as having danced in the cotillion dance at the second ball, including the hostesses daughter, though the hint from the second event is that perhaps there were only four dancers involved (which would be very unusual in what was described as being a Cotillion dance, there were probably eight dancers). It seems likely to me that the same group of performers danced either exactly the same Cotillion-like dance at both events, or a minor variation on the same theme. It was probably a polished dance with fancy steps and crisp synchronisation which had been well rehearsed by a squad of friends in the weeks running up to the balls. This can't be proven of course, it's just a probability based on what we do know. It's also likely that there was relatively little overlap between the guests at the two balls, the second set of guests would have been as appreciative of the performers as those at the first (especially with the promise of luxurious exotic fruits to be enjoyed shortly afterwards).

So what might that dance have been? One possibility is that it was a regular Cotillion dance, perhaps even La Ridicule as described above. This is clearly possible. But the dance at the first ball was described as being

Ultimately we're unlikely to ever know exactly what was being danced at our balls, it's just fascinating to discover something out of the ordinary. Moreover, knowing that they were We've animated suggested arrangements of several of Michael Kelly's French Country Dances (see Figure 10) including his c.1804 No 1 or Pantaloon Figure and his No 2 or Chinese Figure.

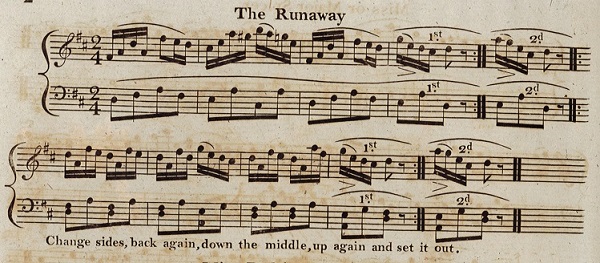

The RunawayThe usual English country dances which followed were preceded by two new ones, both composed by a Lady of distinction; one was the The Runaway, and the name of the other we could not learn.(Countess of Shaftesbury's first ball) The second dance was led off by the Marquis of Hartington and Lady Louisa Vane to the tune of the Runaway, followed by nearly [30?] couple in two sets.(Duchess of Bolton's Ball)

The next tune named as having featured at our 1808 balls was The Runaway, it was described as being a  Figure 11. The Runaway from Skillern & Challoner's c.1808 7th Number

Figure 11. The Runaway from Skillern & Challoner's c.1808 7th Number

The word The tune we're interested in was well published in London between the years of 1808 and 1809. The precise sequence of publication is unknowable but examples include: Campbell's c.1808 1st Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1808 7th Number (see Figure 11), Goulding's c.1808 12th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1808 3rd Book, Monzani's c. 1809 10th Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1809 12th Number, Clementi's c.1809 6th Number, James Platts's c.1809 9th Number, Dale's c.1809 13th Number, Goulding's collection of 24 for 1809, Cahusac's collection of 24 for 1809 and Ball's c.1809 1st Number. It was also named in Thomas Wilson's Treasures of Terpsichore for 1810 and in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ballroom. Yet another version of the tune was published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his c.1810 Morgiana publication. Gow's tune was arranged in a different way to that of the London publications but it's essentially the same melody, it's just in a different key and appears intended to be played a little slower.

We're informed by the correspondent from the Shaftesbury Ball that The Runaway was

In addition to our two balls, the Runaway was also danced at a number of other social events around the year 1808. Examples include: Lord Altamort's Ball at Cambridge (Morning Post, 6th of July 1808) where it was the first dance of the evening and We've animated a suggested arrangement of the Skillern & Challoner version of c.1808 (see Figure 11), the Button & Whitaker version of c.1809 and the Wheatstone & Voigt version of c.1808. For futher references to the tune, see also: Runaway (4) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

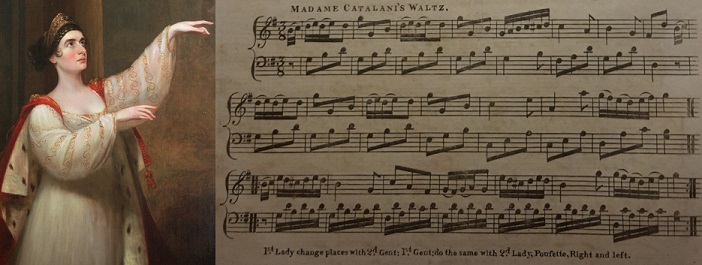

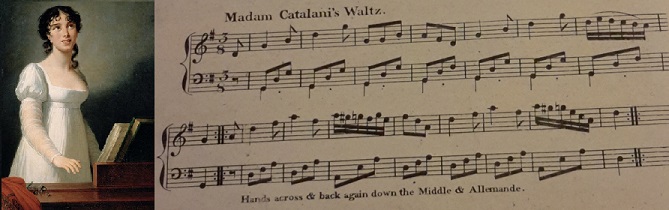

Madame Catalani's WaltzThe Ball was opened a little before twelve o'clock, by the Hon. Mr. Eden and Lady Sarah Spencer, to the admired Air of Catalani's Waltz, followed by nearly 30 couple in two sets(Hon. Mrs Thomas Knox's Grand Ball and Supper) A little before eleven o'clock the Ball was opened by Miss Parry and the Marquis of Tweedale, to the favourite Air of Madame Catalani's Waltz.(Duchess of Bolton's Ball) The next tune to be referenced across our 1808 balls is Madame Catalani's Waltz. This particular tune is difficult to identify as at least four different tunes of that same name all circulated at around the same date. But before we investigate further let's first consider the performer after whom the tunes were named, Angelica Catalani (1780-1849) (see Figure 12). Catalani was perhaps the most celebrated singer of her generation, her performances at the Italian Opera House in London were a sensation, so too was the fee that she was paid to perform there between about 1806 and 1813!  Figure 12. Madame Catalani in Semiramide c.1808 (left) and Madame Catalani's Waltz from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 10th Number (right). Left image is courtesy of the Royal Academy of Music.

Figure 12. Madame Catalani in Semiramide c.1808 (left) and Madame Catalani's Waltz from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 10th Number (right). Left image is courtesy of the Royal Academy of Music.

She was born in Italy and by the age of 16 was performing at La Fenice in Venice. The Prince Regent of Portugal lured her to Lisbon in 1804 to sing at the Italian Opera house there. Her fame grew and she performed in Madrid, Paris and elsewhere. She was signed by the managers of London' King's Theatre Italian Opera House in 1805 for, according to Wikipedia, a salary of £2000 [which was a vast fee]. The Morning Herald newspaper (24th of July 1805) jokingly speculated of her salary:

Madame Catalani was famed as a singer and, as with any stage performer, she would also be required to act in the Theatre's various stage productions. I've not however found any reports of her having danced on the stage, it's therefore a little unusual to find a social dancing tune named in reference to her. Where tunes are named for stage performers it's often because they had famously danced to that same tune; we've previously, for example, investigated Mrs Wybrow's Hornpipe and we've referred to Mademoiselle Parisot's Shawl Dance from La Belle Laitiere above. While it's possible that she did dance to one of the tunes named for her on the stage, this seems unlikely, the tunes were perhaps dedicated to her in her capacity as a celebrated performer. One of the first dated references to a Madame Catalani's Waltz that I can find appears in the Morning Post newspaper for the 6th of July 1807; an advertisement for Lavenu's music shop offered:  Figure 13. Madame Catalani c.1806 (left) and Madam Catalani's Waltz from Joseph Dale's c.1809 14th Number (right). Left image is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 13. Madame Catalani c.1806 (left) and Madam Catalani's Waltz from Joseph Dale's c.1809 14th Number (right). Left image is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

I know of at least four tunes all named Madame Catalani's Waltz that are viable candidates for our tune. In addition to these four were various minor tunes with such names as Madam Catalani's Favorite, Madame Catalani's Fancy and Catlani's Wriggle (such oddities were not widely published and warrant no further investigation). One of our candidate tunes was only (as far as I can discern) published in Hannam's c.1807 4th Number; Hannam was not one of the more significant music publishers and that tune seems not to have been published elsewhere, it's unlikely to have been the popular tune. Another candidate was published in Goulding's c.1811 23rd Number but once again not, so far as I can discern, anywhere else. The Goulding tune is probably not what we're looking for either; besides, Goulding & Co. also published one of the other candidates in their c.1809 15th Number making it a stronger candidate.

The first of our two stronger candidates was published in several works issued in London c.1808; these include Button & Whitaker's c.1808 10th Number (see Figure 12), Clementi's c.1808 5th Number and Walker's c.1808 16th Number. This same tune was also published a decade later in Monro's c.1818 Waltziana. The particular curiosity amongst these publications is that George Walker named the tune

The second strong candidate was published several times in London c.1809. Examples include: Dale's c.1809 14th Number (see Figure 13), Goulding's c.1809 15th Number, Goulding's collection of Twelve Country Dances for 1809 and Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1808 3rd Book. This tune seems to date to a little later than the first candidate but we're operating with estimated dates of publication and there's no certainty as to which came first. It seems likely that where Walker and Clementi were aware of an earlier

I'm unable to say which of the two candidates is more likely to have been danced at our balls of 1808, either candidate is possible. A further publication of interest would be Hodsoll's Collection of the Most Fashionable Country Dances for the Year 1807 which is understood to also contain a tune named For futher references to the tune, see also: Madam Catalani's Waltz at The Traditional Tune Archive.

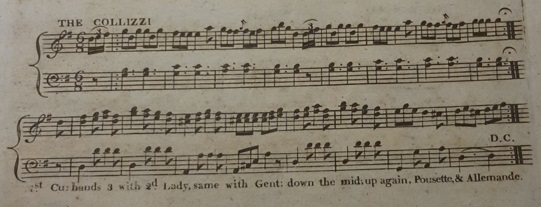

The Collizzi / The ColliggiThe second dance was likewise a new one called The Colizze. It possessed much merit, and had certainly many claims to originality.(Duchess of Bolton's Ball)  Figure 14. The Collizzi from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 12th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 14. The Collizzi from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 12th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The final tune that we found named across our 1808 balls is given as We also lack clues to the identity of the composer of this new tune. It was featured at a ball held by the Duchess of Bolton alongside a tune named Prime of Life, this second tune was probably composed by Miss Bouverie (later Lady Mildmay). We could speculate that Miss Bouverie also composed The Collizzi, there's no evidence for this beyond coincidence so it's just a possibility.

The two musical publications that I've found the tune in are Button & Whitaker's c.1809 12th Number (under the name The Collizzi, see figure 14) and in Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (under the name The Colliggi). The Wheatstone & Voigt publication of c.1806 is interesting as several editions of this work are known to exist, dating these various editions is complicated, the edition that contained The Colliggi may date to as late as 1809. The word We've animated a suggested arrangement of Button & Whitaker's c.1809 version of the dance (see Figure 14) and of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version.

Conclusion

In this paper we've reviewed what's known of seven different balls that were held in Britain in the year 1808. We've encountered several country dancing tunes that were named as having been danced at those events, we've further investigated the six such tunes that we've not studied in previous papers. We've also explored the phenomenon of the French Country Dance as it might have been experienced in 1808, we've considered how it may have helped prepare the nation for the subsequent Quadrille phenomenon of the following decade. We've encountered tunes derived from stage performances, tunes associated with professional bands, tunes composed by a

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved