| Return to Index |

|

Paper 42 Mrs Beaumont's Grand Balls, Part 2: 1811-1821Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 25th February 2020, Last Changed - 5th September 2023]This paper continues our investigation into the grand society balls hosted by Mrs Diana Beaumont (1762-1831), wife of the Northumberland MP Colonel Thomas Beaumont (1758-1829); you might like to read our first paper before continuing with this one. Mrs Beaumont was born the illegitimate daughter of Sir Thomas Wentworth Blackett, 5th bt., of Hexham and Bretton (1726-1792). She would go on to become one of the richest commoners in England, the society balls she hosted were amongst the most prestigious of the London season.  Figure 1 The Beaumont address at 35 Portman Square, from the Horwood Map of 1792-9.

Figure 1 The Beaumont address at 35 Portman Square, from the Horwood Map of 1792-9.

A brief biography of Mrs Beaumont was provided in Part 1 together with an investigation into the balls that she hosted between 1807 and 1810. This paper continues that theme by considering the Beaumont Balls held between around 1811 and 1821, a period that happens to intersect with the Regency proper. There may have been further Beaumont balls held after 1821; the newspaper based evidence that we rely upon to investigate these events cease to mention any such events after that date. Most of the events were held at the Beaumont's London residence at 35 Portman Square (see Figure 1), it was one of the more aristocratic neighbourhoods of the city. The descriptions of the balls are mostly derived from the London newspapers, the degree of detail varies significantly from one event to the next. We'll discover what we can about the balls from the surviving source material. In so doing we'll observe the shifting trends in social dancing across the 1810s, we'll also discover how international politics might influence the dances of the British aristocracy. The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further within this paper are:

Preparations for 1813The year 1813 would be important for the Beaumonts, they were preparing themselves for several seasons in advance. Their metropolitan property in Portman Square (see Figure 1) may have been large but it wasn't one of the largest such mansions; they regularly hosted around 250 people at their Balls, by 1810 they'd hosted 400 (a number they continued to host into 1811), though it must surely have been a squeeze. The following text was printed in the Morning Post newspaper for 27th April 1811, it describes the limit of what their hospitality could manage:  Figure 2 An affecting scene in Hyde Park or Modern Domestic Happiness from March 1813, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2 An affecting scene in Hyde Park or Modern Domestic Happiness from March 1813, image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Lady of Colonel Beaumont entertained upwards of 400 Fashionables on Thursday evening, in Portman-square. Three drawing-rooms were thrown open about ten o'clock; they displayed all the elegance of modern taste. The great eating-room was set apart for distributing refreshments in; here a noble service of new plate (the appendages to a breakfast table), had a very fine appearence; from the judicious manner in which it was set out, the effect was heightened. Card-tables were placed in the centre room.

This event seems not to have involved dancing, rather it was a crowded reception. Mrs Beaumont and her daughters were increasingly visible; we read in Part 1 of how Captain Gronow in his memoires noted that

It's unclear whether the Beaumonts held balls in 1812 but they were certainly preparing to do so; The Globe newspaper for the 14th August 1812 commented that:

Mrs Beaumont's Rout, 18th March 1813The important event was the 1813 introduction into polite society of their now 17 year old daughter Miss Diana Beaumont. This would involve three major activities, a Rout and two Balls; the Morning Post newspaper for the 20th March 1813 wrote of the first: Portman-square exhibited such a scene of life, and gaiety, on Thursday night, as has seldom been witnessed therein, even at the height of the fashionable season. The Carriages about midnight blocked up all the avenues leading thereto. The entertainment being given for the express purpose of introducing Miss Beaumont, in the circles of high life, for the first time, a more than usual display of brilliancy and ornament was distinguishable. Splendour and taste prevailed in every department of the entertainment. The state apartment exhibited their usual style of decoration, except being modernized and enriched with gold; they were lighted up in an unique manner, with candelabras carrying spiral lamps. There were three chandeliers in the three drawing-rooms, but neither were of modern construction. The refreshments were distributed from the great eating room; ices, confectionary, and fruits, were in great request, and abundance. The party did not break up until three o'clock. Present:-  Figure 3 Mrs Crowdem's Rout 1829, courtesy of Yale University Library.

Figure 3 Mrs Crowdem's Rout 1829, courtesy of Yale University Library.

The Prince and Princess Castelcicala.

This The foreign dignitaries were probably members of the various diplomatic details present in London; the largely English nobility present bore an impressive selection of titles, though many leading socialites were absent. The Beaumonts may have been unlucky, Jane Gordon, the Duchess of Gordon (c.1748-1812) had died the previous year; she had been a prominent member of London's privileged social circles, her children were married into several of the nation's most splendid families; they appear to have been abstaining from social events in 1813 perhaps as a public sign of mourning. It might have been hoped that a suitable suitor would emerge to seek the hand of Miss Beaumont at this event, perhaps someone with a title from a great aristocratic family, or maybe a foreign prince. The details of her subsequent biography remain vague but she seems never to have married, whatever offers may have been made seem not to have been accepted. She retained the name Miss Beaumont into the 1830s, I've been unable to establish much about her life thereafter.

Mrs Beaumont's First Grand Ball, 2nd April 1813The Beaumonts held two balls one week apart in April 1813, both events were held on Friday evenings. Their property was perhaps a little too small for what was planned (despite the enlargement of 1812) and so invitations to the guests were split over two separate evenings. The following description of the first evening was published in The Morning Post newspaper for the 5th April 1813, dance references have been highlighted in bold. Beaumont House, in Portman-square, was opened on Friday evening, to the gay world. This party, although composed of many of the leading titled personages in the fashionable hemisphere, was not to be compared to the splendid assembly held there about two years since. The company did not exceed 300 persons, and it may there fore be called a select circle. The hall, stair-case, gallery, and the three drawing rooms, were lighted up about ten o'clock, with chandeliers, lustres, lamps, and illuminated vases. The apartments on the ground floor, consisting of the library, morning rooms, and banquetting-room, shone with a brilliancy equally resplendent. Dancing commenced withThe Regent's Medley, about eleven o'clock, led off by Mr F Montague and the accomplished Miss Beaumont. Among the couples were:  Figure 4

Figure 4 Tea, Coffee and Chocolate. 1786 (top left), 1762 (bottom left), and 1805 (right). All images courtesy of Yale University Library. Prince Koslovsky - Lady E. Cecil... Question that are sometimes asked of the dancing at these balls include how old the dancers were and what their martial status was. I thought it might be interesting to consider those questions for the partners named above, most of whom can be identified with a reasonable degree of certainty. They were probably:

Mrs Beaumont's Second Grand Ball, 9th April 1813The second of the two Beaumont balls of early 1813 was described over two editions of The Morning Post newspaper. The following narrative is from the edition for the 12th April 1813, dance references have been emphasised in bold. Beaumont-house, in Portman-square, was again opened to the world of fashion, on Friday evening. The same splendour, taste, and spirit prevailed, as is usual at all the Lady's entertainments. The utmost magnificence preponderated, throughout all the state apartments, in respect to the costly articles in bijutry and or-moulu. On one floor there were exhibited no less than five drawing-rooms, all correspondently furnished with the riches of almost every age and country. The ball-room, that beautiful apartment, was illuminated with peculiar brilliancy; the floor was chalked with groupes of dancing figures; i.e. Bacchantes, &. At an early hour arrived his Royal Highness the Prince Regent, accompanied by Colonel Bloomfield. About the same period came the Duke of Clarence, and Miss Fitz-Clarence. To these may be added, the Royal Dukes of Cambridge and Gloucester. At eleven o'clock, the ball was opened with a new dance calledThe Isle of Franceby Lord James Hay and the accomplished Miss Beaumont. Among the couples who followed were:-  Figure 5 Examples of dancing on chalked (or perhaps water-coloured) floors, 1818 (above) and 1816 (below). The Beaumonts had images of dancing figures chalked on their floor in 1813. Both images courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 5 Examples of dancing on chalked (or perhaps water-coloured) floors, 1818 (above) and 1816 (below). The Beaumonts had images of dancing figures chalked on their floor in 1813. Both images courtesy of the British Museum.

Mr Wentworth Beaumont - Lady Charlotte Graham The narrative continued on the 14th April 1813: Dancing ceased for about an hour, at two o'clock. The company then adjourned to the supper-tables. Here a most sumptuous display indeed was made; there were no less then six supper-rooms, all fitted up in the most beautiful and appropriate manner. Each table was brilliantly ornamented with trophies of war and peace; emblems emblematic of the arts and sciences; the costume of all the civilized nations on earth, exemplified in waxen images, modelled for the fete expressly. In short, were we to attempt any thing like a full description of the scene, it would occupy a space much greater than our limits would admit of. Suffice it to say, that, what with the plate, and the china, displayed, and the brilliancy of the lighting up of the tables, the effect was grand in the extreme. To render the coup doeil complete, about two hundred beautiful women (for the major part of the females were really beautiful) sat in such prominent situations as to be seen in every part without the least difficulty. The supper, we need not add, was most excellent; the wines abundant, and all of the rarest kinds. The desert, fruits, and confectionary, were equally deserving of panegyric; the Duke of Clarence spoke raptures of them. The music re-commenced with Spanish dances at half-past three o'clock; French figures succeeded. The whole concluded at seven o'clock in the morning, with reels and strathspeys. A dejeune followed.... [4 Marquisses, 6 Marchionesses, 8 Earls, 11 Countesses, 8 Lords, 45 Ladies, 2 Sirs, 1 General, 3 Captains, 1 Count, 17 Messrs, 15 Mistresses, 18 Misses]. The guest list for this ball was the most impressive to date, the Prince Regent was present in person along with three Royal Dukes (his brothers). The dancing was led off by three of the Beaumont children and the entertainments were on a scale even more lavish than in previous such balls. We can attempt once again to identify the age and marital status of the named dancers:

Christmas FestivitiesThe Beaumonts split their time between their estates in Yorkshire and the London season. They had two main properties in the north, one at Hexham Abbey and the other at Bretton Hall (see Figure 6); Christmas of 1813 found them at home at Bretton. They hosted a ball there that would be described in The Morning Post for the 10th January 1814 as follows, dance references are once again in bold:

Figure 6 Bretton Park, 1830. Image courtesy of ancestryimages.com.

The magnificent seat of Colonel and Mrs Beaumont, near Wakefield, has been the scene of much elegant festivity. Dinners, concerts, and card-parties have been held there in regular succession since the eve of Christmas-day. Last week a splendid ball and supper were given, to which all the neighbouring Nobility and Gentry were invited. A new and spacious room was opened, for the first time, built by Mr Jeffrey Wyatt, who has lately renovated the whole interior of the mansion. We're once again reminded of the Beaumont's fabulous wealth; their Yorkshire neighbours must have been aware of the the Beaumont's having hosted the Royal family the previous summer, this event would be of a similar scale to those of their London balls. The Beaumonts had even brought the most celebrated country-dancing band with them from London, that of the Gows (led, presumably, by John Gow). It must have made an impact!

Further events for 1814The newspapers could be fickle, they might dedicate many column inches to one event and barely mention another; so it was for the rest of 1814, mere hints of activity are alluded to.

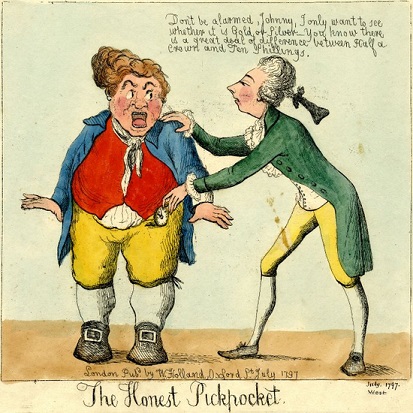

The Morning Chronicle for 27th April 1814 wrote:  Figure 7 The Honest Pickpocket, 1797. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 7 The Honest Pickpocket, 1797. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Morning Chronicle for the 17th May 1814 wrote: This event is of some interest; two of the most prestigious bands in London were involved in two different rooms, one (presumably led by John Gow) for country dancing and the other (presumably led by Edward Payne) for waltzing; this is the first clear reference to waltz dancing having been enjoyed at a Beaumont ball.

Events for 1815

The Morning Post for the 13th April 1815 recorded another Beaumont Rout, sadly the event clashed with a different society event on the same day; they wrote: The Beaumonts also hosted a ball in October 1815 following the Doncaster Races (Morning Chronicle, 14th October 1815). Their major event for the year was a grand ball that was held on the 1st of June 1815, the Morning Post newspaper (3rd June 1815) recorded of it (with dance references once again in bold): One of the most magnificent balls the season has produced, took place on Thursday evening in Portman-square, at the superbly fitted up residence of Col Beaumont, in Portman-square.  Figure 8 Ormolu lights with lustres of a style that might have been used by the Beaumonts, c.1790, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 8 Ormolu lights with lustres of a style that might have been used by the Beaumonts, c.1790, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Lord Algernon Percy - Miss Mary Anne Beaumont... [2 Duchesses, 3 Marquisses, 3 Marchionesses, 9 Earls, 8 Countesses, 9 Lords, 28 Ladies, 6 Sirs, 1 General, 1 Captain, 13 Messrs, 4 Mistresses and 4 Misses].

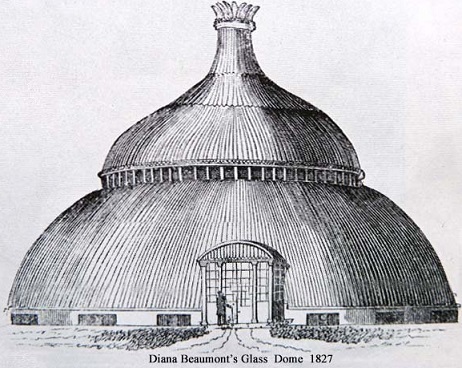

A recurring observation from the Beaumont Balls is their splendid arrangement of exotic fruits. This may have been a particular lure, a guest might accept an invitation based purely of the promise of fresh fruit. The Beaumonts had constructed large The named dancers for the first country dance on this occasion were probably:

Grand Ball in 1817

The newspapers recorded in early April 1816 that Mrs Beaumont would be hosting another ball on the 15th (Morning Post, 2nd April 1816), but accounts of the event itself seem not to have been published. Similarly vague statements were printed regarding an event in April 1817 (Morning Chronicle, 23rd April 1817):  Figure 9 A Quadrille being danced, possibly in a private home, image courtesy of the New York Public Library

Figure 9 A Quadrille being danced, possibly in a private home, image courtesy of the New York Public Library

A Grand Ball held on the 19th May 1817 was described in detail, the following text is from the Morning Post newspaper for the 21st May 1817 (dance references are emphasised in bold): This was the first of the Beaumont balls to explicitly feature quadrille dancing, it's also the first for which the inclusion of Country Dances is uncertain - they may not have been danced at all. The named quadrille dancers are of a less identifiable class than those of previous Beaumont balls, it's difficult to discern with any certainty who many of them were. Quadrille dances were choreographed performances, the dancers were expected to have memorised the figures in advance; perhaps the more aristocratic dancers had yet to memorise the Quadrilles. Perhaps these eight dancers had spent time together rehearsing the figures of their Quadrille, they may have been close friends who regularly danced together.Mrs Beaumont's Grand Ball in Portman-square, on Monday evening, was upon the most magnificent scale. The noble drawing rooms, the range of apartments below, the hall, and staircase, put on all their attractions. The ball was opened at eleven o'clock, with Quadrilles, in the principal room, the floor of which was decorated with trophies (naval and military), emblems of music, &c. encircled by mosaic borders. Among the couples were -

A further observation we might recall is the cruel anecdote shared by Captain Gronow in the first part of this paper; Gronow quoted Mrs Beaumont as having told him that

Balls held between 1818 and 1820

The Morning Post for the 31st March 1818 recorded that  Figure 10

Figure 10 The hot and succession housesat Bretton Hall, where the Beaumonts grew their pineapples and the other exotic fruit served to their guests in London; it was demolished in 1833 after Diana's death. Image courtesy of bretton-hall.com Two newspapers reported on a Ball held on the 9th June 1818, neither provided much detail. The Morning Post for the 11th June 1818 printed a report which seems very similar to earlier descriptions they'd published of Beaumont balls: This distinguished fashionable Lady gave a superb Ball and Supper on Monday evening, in Portman square. The drawing-rooms put on all their attractions at ten o'clock. Dancing commenced at eleven with quadrilles, in which Miss Mary Anne Beaumont greatly shone. A sumptuous supper was arranged, at two o'clock, in the Great Banquetting-room, on the ground-floor, with a desert matchless in every respect, consisting of a profusion of pine apples, grapes, peaches, and apricots, all brought from the Colonel's hot and succession-houses, erected on the grounds of Briton-hall, in Yorkshire. In the centre of the table stood a gold epergne of great value; it was illuminated by twelve pair of branches, carrying three lights each. The dancing concluded with waltzes. About 400 persons were present The Morning Chronicle for the 9th of June 1818 placed the event on the following day, and wrote: Mrs Beaumont gave on Tuesday evening, one of the grandest balls of the season, at her mansion in Portman-square; the whole suite of apartments on the drawing-room floor were thrown open, they were decorated with a profusion of pots of the choicest flowers, and were most brilliantly illuminated. The principal drawing-room and the adjoining one, were appropriated for dancing, the floors of each were beautifully chalked, in the centre of each was suspended a costly cut-diamond lustre, side lights, &c. The ball commenced soon after eleven o'clock. The supper, which was of the first description, was announced at one, it was prepared in the grand parlour, the library, and two other rooms, where covers were laid for nearly 400. The merry dance recommenced at half-past two and continued till nearly six yesterday morning. To enumerate the company would be to name all the leading and distinguished fashionables in town. The Morning Post for the 20th May 1819 wrote of another ball: A very splendid Ball was given on Monday evening by the above Lady, to 500 fashionables, at her elegant residence in Portman-square. The very fine apartments in that noble mansion were brilliantly lighted up. Dancing commenced at a quarter past eleven, with quadrilles, led off in capital style by the Misses Beaumont. A similar pattern repeated itself in 1820, both newspapers reported on what was now considered to be an annual ball, but with notable editorial differences. The Morning Post for the 10th of June 1820 wrote: In Portman-square, on Thursday evening, a splendid Ball was given. The three drawing rooms were fitted up for the occasion with infinite taste; two for dancing, and one for refreshments.  Figure 11 Regency Fete, or John Bull in the Conservatory, 1811. Image courtesy of Yale University Library

Figure 11 Regency Fete, or John Bull in the Conservatory, 1811. Image courtesy of Yale University Library

Whereas, the Morning Chronicle on the 12th June 1820 wrote: Mrs Beaumont opened her splendid mansion in Portman-square, on Thursday night, with one of the most brilliant fetes of the present season. Seven hundred persons of distinction had been invited, and there were nearly that number present. The house was crowded with beauty and fashion, in every part, even to the corridors. The grand drawing room, fronting the square, was prepared for the ball. The banquet was served upon magnificent services of massive silver plate, in the front and back drawing rooms on the ground floor. It was a stand-up supper, and the tables, which were loaded with the choicest viands, were continually replenished. Pines, nectarines, peaches and grapes, in the utmost abundance, having been brought from the Colonel's very extensive hot-houses, at his seat in Yorkshire. The illuminations were most brilliant, and the company did not retire till between four and five o'clock.

Mrs Beaumont's Grand Ball, 1821The last Beaumont Ball to be described in detail was held in 1821; there may have been subsequent balls, but the newspapers appear not to have written about them. The Morning Post for 23rd of May 1821 wrote: The above fashionable Lady gave her Annual Ball and Supper, in Portman-square, on Monday evening, in the same style of magnificence as usual. The Morning Post had been complaining of the lighting at the Beaumont Balls for a couple of years at this point, the Beaumonts were yet to adopt the modern miracle technology of gas lighting, they were depicted as being a little old fashioned in consequence. Gas based lighting was a new (and dangerous) technology in the 1810s, there were seven gasworks servicing London alone by 1822, several mansions had already adopted the technology.

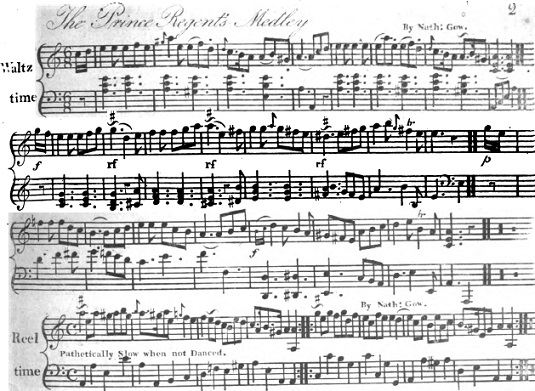

Figure 12 The Prince Regent's Medley from Nathaniel Gow's 1811 The Marquis of Queensberry's Medley

Figure 12 The Prince Regent's Medley from Nathaniel Gow's 1811 The Marquis of Queensberry's Medley

The Regent's MedleyDancing commenced with The Regent's Medley, about eleven o'clock, led off by Mr F Montague and the accomplished Miss Beaumont(First 1813 Ball) The second dance was The Regent's Medley, when Miss Beaumont again took the lead with Lord Sunderland.(Second 1813 Ball) This tune was used at both 1813 Beaumont balls, the second of which was attended by the Prince Regent in person, the tune was presumably used in tribute to the Prince himself. Miss Diana Beaumont (the eldest of the Beaumont daughters) was now 17 and was being introduced to fashionable society, she led off the dancing at both events with a suitably eligible partner. Medley dances usually combine two different tunes together, typically a Strathspey and a Reel; these longer arrangements lend themselves to a more complicated dancing figure than does the typical Country Dance, figure sequences with five or more parts might be introduced. Such arrangements are popular amongst modern dancers, but they tended not to be danced so often two hundred years ago; they were unforgiving dances, the first couple might be exhausted by the effort of dancing down a set to such a lengthy tune. If a medley were danced then it might be the most memorable dance for an entire Ball.

A tune named

Nathaniel Gow published a tune in Edinburgh named

What is certain is that a tune of this name was danced at several society balls. The first such reference is from Mrs Calvert's Ball (Morning Post, 13th May 1811) in 1811 where it was described as

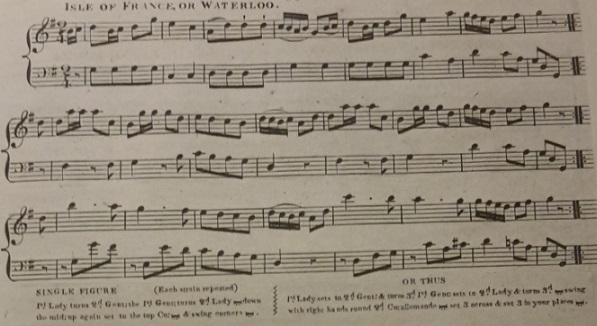

I don't know of any suggested dancing figures having been published for use with this tune. If you decide to dance it you might like to select a new arrangement of  Figure 13 Isle of France, or Waterloo with Figures by Thomas Wilson, from Button & Whitaker's c.1816 30th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 13 Isle of France, or Waterloo with Figures by Thomas Wilson, from Button & Whitaker's c.1816 30th Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Isle of FranceAt eleven o'clock, the ball was opened with a new dance called The Isle of France by Lord James Hay and the accomplished Miss Beaumont(Second 1813 Ball)

The name A tune named Isle of France was published in numerous London dance collections from around 1815, two years after the date of our ball, it seems not to have been widely known in 1813. If the 1815 tune was the same tune danced at the Beaumont's 1813 ball then perhaps it was composed by someone personally known to the Beaumonts. Our Beaumont ball is the only society event at which a tune of this name is known to have been danced, perhaps the Beaumonts were responsible for promoting it. The tune was published numerous times under the name Isle of France, then from mid 1815 it acquired the new name of The Waterloo Dance. Several tunes circulated under that name in the immediate aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo, it's unclear whether there's any significance to our tune having been thus renamed. The new name may have given the tune a new popularity as anything themed around the victory at Waterloo was liable to sell. Publications of the tune in London under the original name include: Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1815, Dale's c.1815 22nd Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1815 10th Book, Hodsoll's c.1816 25th Number and James Platts's 1816 48th Number. It was also published in Clementi's c.1817 24th Number under the name Waterloo Dance, and in Button & Whitaker's c.1816 30th Number under the name Isle of France, or Waterloo (perhaps they had recognised that the tune was already in circulation under another name see Figure 13). We've animated suggested arrangements of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1815 version of the dance, of James Platts's 1816 version, Button & Whitaker's 1816 version (with figures by Thomas Wilson, see Figure 13) and of Clementi's c.1817 version.

Figure 14 This c.1807 image derives from an anonymously printed piece of music of uncertain date which is simply titled "Fandango".

Figure 14 This c.1807 image derives from an anonymously printed piece of music of uncertain date which is simply titled "Fandango".

Spanish DancesThe music re-commenced with Spanish dances at half-past three o'clock(Second 1813 Ball) Quadrilles, waltzes, and Spanish dances, were introduced.(1821 Ball)

It's not entirely clear what would have been understood by the phrase

It's possible that the variant of Country Dancing known in London as Spanish Country Dancing was introduced. This style of dancing seems to have been invented (perhaps just promoted) in the mid 1810s by a dancing master named Edward Payne, it's unclear how successful these dances were. The Beaumonts would hire Payne's band for their 1814 ball and could easily have done so in 1813 too; it's entirely possible that Payne taught the assembled company his new style of

French Figure Dances... French figures succeeded(Second 1813 Ball)

The concept of a

Reels and StrathspeysThe whole concluded at seven o'clock in the morning, with reels and strathspeys.(Second 1813 Ball) ... and concluded with reels, at half past six o'clock.(Christmas 1813 Ball) the evening concluded with reels and strathspeys.(1815 Ball)

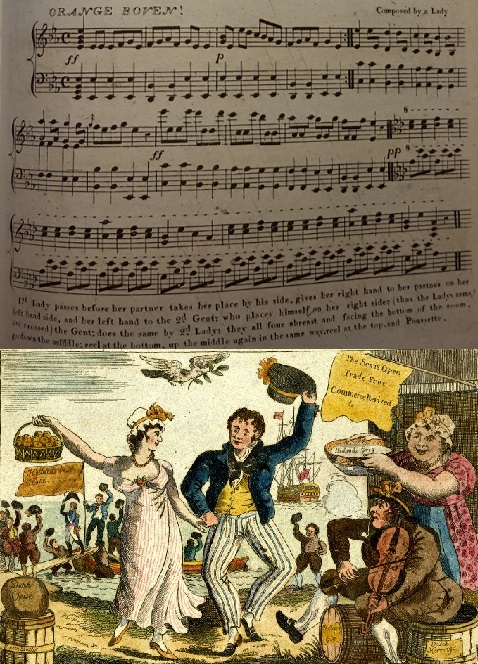

We've studied the concept of  Figure 15. Orange Boven! from James Platts' c.1814 40th Number (top); an 1814 print subtitled Jack Jolly jigging to the tune of Orange Boven celebrating peace (bottom). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 15. Orange Boven! from James Platts' c.1814 40th Number (top); an 1814 print subtitled Jack Jolly jigging to the tune of Orange Boven celebrating peace (bottom). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED; lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Orange BovenThe ball was opened at eleven o'clock, with the new dance Orange Boven, by Mr Stanhope and Miss Beaumont. Two sets followed, of twenty-five couple in each.(Christmas 1813 Ball)

The term The term may have been old but it was rarely used in England prior to the end of 1813 - the date at which the Netherlands rebelled from Napoleonic France. The French authorities in Amsterdam were being deposed in the aftermath of the October 1813 Battle of Leipzig, a new and popular Dutch government was in the process of emerging under the current Prince of Orange (1772-1843). The Dutch used the phrase as a slogan that promoted national pride. The title of the tune therefore had significant political and patriotic implications. The British public were anticipating peace in Europe (see Figure 15), they were also celebrating a French defeat; perhaps they were also aware of a potential union forming between the royal houses of Hanover and Orange, the hereditary Prince of Orange (1792-1849) was the leading candidate to wed Princess Charlotte (1796-1817) (the couple would be formally engaged in 1814, though the union never came to fruition).

Jingoistic political slogans such as Orange Boven and White Cockade (which we'll consider below) were ubiquitous in 1814 as Napoleon's empire was visibly crumbling; it's no surprise that a tune circulated with this name at around this date. The challenge for us is that there wasn't just one tune, there were actually a dozen or more different tunes all named Orange Boven that were published in London at about the same c.1814 date. There's no reliable way to predict which tune was used at our Ball. Searching for the phrase Orange Boven in one of the Newspaper archives I use yields a mere 10 instances of the phrase in print between 1750 and the end of October 1813, then 82 for the remainder of 1813, and a further 90 for 1814. The phrase went from being almost unprinted to being widely used within a single month. In addition to dances there were also songs and poems titled All of the London music shops that were still issuing Country Dances collections will have had a tune of this name within their portfolio; a few of the shops printed the same tune but there is insufficient commonality between them to read much significance into this. Some of the tunes were first printed in 1815 or 1816, such tunes are unlikely to have been used at the Beaumont ball; it's possible that the Beaumont tune was never published at all. Tunes named Orange Boven include:

Tunes named Orange Boven were danced at some society events; in addition to our Beaumont ball an example also featured at the Ball at Beddington House (Morning Post, 11th January 1814) at which The nature of social dancing in London was beginning to change from around the start of 1814, a new mood seems to have emerged that gained momentum into 1815 and beyond. The reports of society balls in the press became less likely to name country dancing tunes, or even to refer to country dancing at all; they're more likely to refer to waltz dancing or generic unspecific dancing. This in turn reduces our ability to investigate such references as were printed beyond that c.1814 date. If tunes were popular then they may still only be known from a single reference (with a few notable exceptions some of which we'll encounter below). Country Dancing didn't cease, but it did become a less conspicuous element of society balls.

The SicilianThe dancing was resumed at three, with the Sicilian dance(Christmas 1813 Ball) We've studied this tune in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. The Sicillian was a tune that was thought to be new but had actually been danced since around 1769.

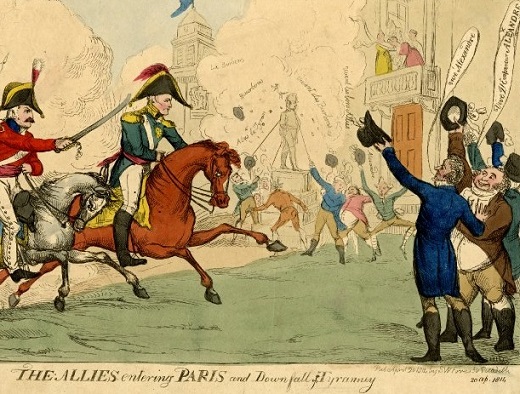

The Couple WaltzThe two principal drawing-rooms were appropriated for dancing in, the first for country dances, the other for waltzes. Mr Gow's and Mr Payne's bands attended.(1814 Ball) After the country dances, waltzes were introduced....After supper waltzing took place(1815 Ball) Waltzes were danced, at the same time, in the adjoining room, which was tastefully fitted up.(1817 Ball) The dancing concluded with waltzes.(1818 Ball) Quadrilles, waltzes, and Spanish dances, were introduced.(1821 Ball)  Figure 16 Field Marshall Blücher and Tsar Alexander entering Paris on the 31st March 1814, the war-weary townsmen wear White Cockades in their hats to welcome them. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 16 Field Marshall Blücher and Tsar Alexander entering Paris on the 31st March 1814, the war-weary townsmen wear White Cockades in their hats to welcome them. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The waltz as a form of music had been known in Britain since around the year 1790; the dance arrived in Britain around 1800 (though its origins are much older), we've written about The Waltz in another paper - you might like to follow the link to read more. The dancing at the Beaumont balls was changing and 1814 seems to have been the pivotal year, Waltzing increasingly replaced Country Dancing at their events thereafter. Their 1814 ball involved Country Dances and Waltzes being enjoyed concurrently in different rooms, by 1817 the country dancing had almost disappeared from their events entirely. 1814 was the year in which the Waltz couple-dance arrived at the Beaumont balls, it was also (arguably) the year in which it conquered London; a delegation of foreign princes led by the Tsar Alexander of Russia visited London in June 1814, the Waltz was widely danced at the society events that the dignitaries attended. Dancing the Waltz may, at least at first, have been seen as a celebration of victory and peace. Napoleon had been removed from office shortly before the date of the Beaumont ball, a celebratory mood would have been in the air. The peace in Europe didn't last of course, 1815 would see a resurgent Napoleon and the Battle of Waterloo; but the dancers of 1814 weren't to know that. Britain's empire fought wars around the world, Europe may have been the primary theatre of action but it wasn't the only such arena. The Anglo-American War of 1812 was still being fought in 1814, any celebration of general peace was therefore a little premature; but the European war held the bulk of the British public's attention - peace in Europe was of great significance to the British public. The celebratory mood was genuine and the waltz dance may have been an expression of that mood.

The White CockadeThe ball was opened at half-past eleven o'clock with The White Cockade, by Lord Hotham and Miss Beaumont. About fifteen couple followed.(1814 Ball)

This was the last of the named tunes to be danced at the 1814 ball, it was led off by the now 18 year old Miss Diana Beaumont and the 19 year old Beaumont Hotham (1794-1870), 3rd Baron Hotham. The tune selected was another with significant political implications; a

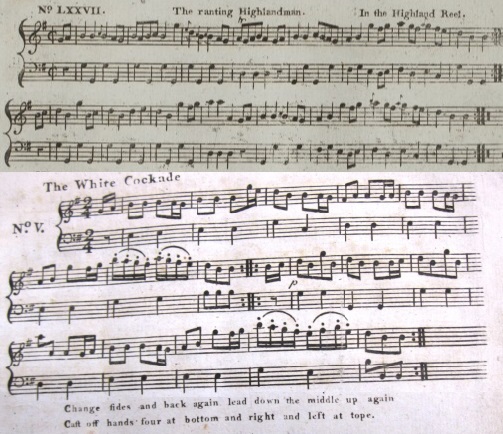

The  Figure 17 The Ranting Highlandman from Thompson's c.1789 Caledonian Muse (above) and The White Cockade from Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (below).

Figure 17 The Ranting Highlandman from Thompson's c.1789 Caledonian Muse (above) and The White Cockade from Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (below).

As the allied forces fought through France in early 1814 the populace of the captured areas would wear the white cockade almost as a symbol of surrender; for example, the Irish publication Saunders's News-Letter for 22nd January 1814 reported:

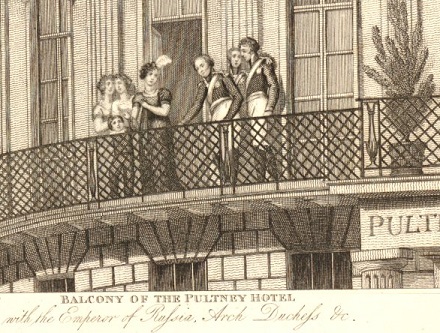

The French monarchy were deposed in 1793 as part of the French Revolution. The last Bourbon King had been Louis XVI (1754-1793), he was guillotined in early 1793. His surviving son, Louis Charles (1785-1795), was considered by the monarchists to be the legitimate Louis XVII; he died of illness, some suggest poison, in 1795. On his death his Uncle, Louis Stanislas Xavier (1755-1824) (the brother of the former King), claimed the title of Louis XVIII for himself. He lived in exile in England between 1808 and 1814, he joined his younger brother (the future Charles X (1757-1836)) and nephews in doing so. The younger Bourbon princes, nephews of Louis XVIII, were regular guests at London's society events; the 37 year old Duke of Angouleme (1775-1844) and the 35 year old Duke of Berry (1778-1820) were present at the second of our Beaumont balls of 1813. The various European powers supported different candidates to rule France following the removal of Napoleon; some favoured Napoleon's son, others favoured one of Napoleon's generals, Britain supported the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy; the French public wore their white cockades in approbation for that restoration. History is rarely that clean of course; the Bourbon loyalists were responsible for a counter-revolutionary movement in 1795 known as the An existing tune named White Cockade had become popular in London back in the late 1780s; this tune had remained in print almost continuously thereafter through to 1814 when it suddenly became important. This tune was widely republished in 1814. In addition to our Beaumont ball it was also danced at such society events as: the Duchess of Montrose's Ball (Morning Post, 30th June 1814), the Fete at Wanstead House (Morning Post, 1st July 1814), the Ball at Stratton (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 9th July 1814), Lady Carrington's Ball (Morning Post, 14th July 1814), Lord Boringdon's Ball (Morning Post, 17th February 1815) and A Ball aboard his Majesty's ship Prince (Hampshire Chronicle, 24th July 1815). It was genuinely popular in 1814, the perfect tune to match the public mood.  Figure 18 Tsar Alexander on the balcony of the Pultney Hotel in Piccadilly, June 1814. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 18 Tsar Alexander on the balcony of the Pultney Hotel in Piccadilly, June 1814. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

This tune may have been popular in the 1780s but its origins were somewhat older. The first publication of the tune under the name White Cockade that I can identify was issued in London in David Rutherford's c.1764 Complete Collection of 200 Country Dances, Volume 2; its origins are a little more complicated however. It would reappear in William Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (see Figure 17); Campbell routinely published tunes that would go on to be popular with the other London publishers, he wasn't the first to print this tune but he did trigger further interest. It was then published in Thompson's c.1790 New Collection of Twelve favourite Cotillons and Twelve popular Country Dances, Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1790, the Preston, Campbell and Skillern collections of 24 Country Dances for 1790 and in Longman & Broderip's c.1791 First Book. It can also be found in Scottish publications such as the c.1794 fourth volume of Aird's collection, in Thomas Calvert's c.1799 collection and in Niel Gow's 1802 Repository of the Dance Music of Scotland, Part 2. Back in London it would be published in one of Dale's c.1800 collections, Andrew's c.1806 10th Number, Goulding's 1814 32nd Number, twice in Thomas Wilson's 1816 A Companion to the Ball Room, in James Platts's c.1815 46th Number, in Button & Whitaker's c.1815 29th Number and in Monro's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1817. It would also be published in Edinburgh in Nathaniel Gow's c.1814 The King Shall Enjoy his own again, and in several c.1820 Quadrille collections.

Wearing of the We've animated suggested arrangements of William Campbell's c.1788 version (see Figure 17), James Platts's c.1815 version, and of John H. Gow's 1821 Quadrille arrangement. For futher references to the tune, see also: White Cockade (1) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

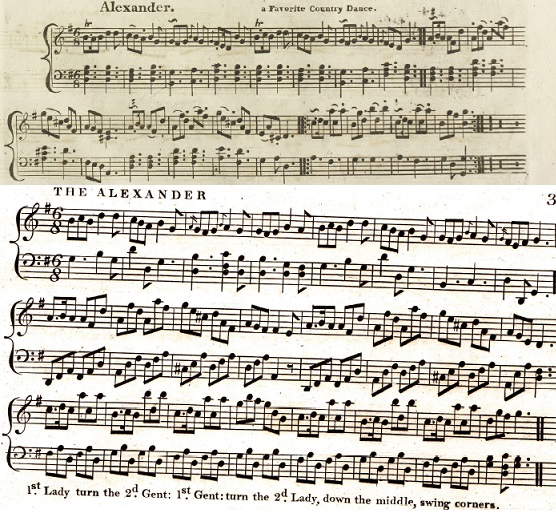

The AlexanderDancing commenced at eleven o'clock, led off with the new and favourite tune of Alexander, by the Earl Percy and Miss Beaumont.(1815 Ball) This was the last of the named tunes (that is, a named tune for which we know the name) to be used at a Beaumont ball, it was led off by the now 19 year old Miss Diana Beaumont and the 30 year old Earl Percy. The dedicatee for the tune is readily identified as Tsar Alexander I of Russia (1777-1825), the hero of the 1814 Battle of Paris that ultimately forced Napoleon to abdicate. He triumphantly entered Paris at the end of March 1814 (see Figure 16). The Parisians had reason to be alarmed, Alexander's critics expected revenge for the Grande Armée's invasion of 1812 and the Firing of Moscow; but the transfer of power was (after the fighting was over) surprisingly orderly - Alexander brought peace rather than retribution.  Figure 19 Alexander in Nathaniel Gow's 1816 Marquis of Tweeddale's Favorite (top) and in Hime's c.1815 22nd Number.

Figure 19 Alexander in Nathaniel Gow's 1816 Marquis of Tweeddale's Favorite (top) and in Hime's c.1815 22nd Number.

Tsar Alexander and his entourage visited London (see Figure 18) in June of 1814 ahead of the 1814-1815 Congress of Vienna, he was accompanied by his sister the Duchess of Oldenburg (1788-1819), the King of Prussia (1770-1840), the Chancellor of Austria (1773-1859) and Marshall Blücher (1742-1819) amongst others. 1814 was a year of celebration for Britain, the Tsar's visit marked arguably the peak of excitement but it wasn't the only such event; the Our tune emerged c.1814 though its origins remain mysterious. The publisher James Platts claimed in his copyright disputes of 1815 to have purchased the rights of a rondo named The Alexander from Mr Bohmer in April 1815; he further alleged that Charles Wheatstone had simplified the tune into a Country Dance for his 1815 33rd Number. Wheatstone refuted the claim, he testified that the tune had been composed by a Mr Bevan. I've been unable to locate copies of either of their publications in order to confirm these claims; you can read more about their copyright disputes in our paper on that subject. Rondo arrangements of tunes tended to be published after a country dance had already become popular, rather than the other way around, so the chronology is a little suspicious.

Surviving copies of the tune are available from several sources including: Hime's c.1815 22nd Number (see Figure 19), Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1816 11th Book and Monro's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1817. A version was also published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his 1816 Marquis of Tweeddale's Favorite publication where it was described as The tune was danced at our Beaumont ball in 1815, it was also danced at The Marchioness of Camden's Ball a few days later (Morning Post, 7th June 1815) and at Nathaniel Gow's Ball in Edinburgh in March 1816. I'm unable to confirm use of the tune at any other society events. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Hime's c.1815 version (see Figure 19) and of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1816 version.

QuadrillesThe ball was opened at eleven o'clock, with Quadrilles(1817 Ball) Dancing commenced at eleven with quadrilles, in which Miss Mary Anne Beaumont greatly shone.(1818 Ball) Dancing commenced at a quarter past eleven, with quadrilles, led off in capital style by the Misses Beaumont.(1819 Ball) Quadrilles, waltzes, and Spanish dances, were introduced.(1821 Ball) The nature of the Beaumont balls changed quite significantly from 1817 when the Quadrille dance become the favoured form of entertainment. The Quadrille tended to offer a shorter burst of excitement than did a traditional Country Dance, something which a group of (usually) eight dancers would enjoy together. The Quadrille is something we've written about in other papers, you might like to follow the link to read more about the First Set of Quadrilles.

ConclusionWe've seen significant changes emerge from the Beaumont ballroom over the course of less than a decade. Their balls of 1813 were similar to those held over the preceeding decade (as studied in our preceding paper), they mostly consisted of Country Dancing with Reels, Strathspeys and a few novelty dances included. The celebratory year of 1814 saw the introduction of the Waltz followed in 1817 by the Quadrilles; the older style of dancing was largely replaced thereafter. We've also seen tunes of patriotic significance being danced; these tunes were able to command interest at a time when dance tunes were less likely to be named (that is, at a date when the public were perhaps less interested in knowing the names of the tunes). It's uncertain whether the Beaumonts continued holding balls into the 1820s, they may have done so but the newspapers tend not to mention them. The Beaumont's children were growing older of course, the imperative to have them find suitable partners may have waned over time.

The Beaumont Balls that we've investigated over some 20 or so years will have been representative of similar events held around the country by other hosts; the Beaumonts were fabulously wealthy and their balls were correspondingly glamorous, the tunes and dances enjoyed will have been danced elsewhere at similar dates. If you'd like to dance them at your own We'll leave this investigation here. If you have more information to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved