| Return to Index |

|

Paper 38 Dancing at the Oatlands Fete, 1799Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 27th September 2019, Last Changed - 24th May 2025]The Royal Family held a garden party at Oatlands Palace near London in mid-1799, it was no more important to them than any of the many similar balls and fetes that they would attend each year, but on this occasion several reports of the dancing survive. In this paper we'll consider what we can learn about the dancing at the historical event.  Figure 1. Oatlands House in the early 19th Century. Image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 1. Oatlands House in the early 19th Century. Image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

The Oatlands FeteA royal palace had existed at Oatlands in Surrey since the 16th century, Oatlands was the home of the Duke and Duchess of York at our date of 1799; the occupier, Prince Frederick, Duke of York (1763-1827), was the second son of the monarch King George III and younger brother to the Prince of Wales. Frederick was effectively the Commander-in-Chief of the British armed forces, his wife (the Duchess of York) was Princess Frederica Charlotte of Prussia (1767-1820).

Their home at Oatlands had been seriously damaged in 1794 when a fire broke out in the laundry that then spread to the armoury, 40lbs of gunpowder were reported to have exploded; fortunately the damage was constrained to a single wing and that was rapidly rebuilt. Oatlands remained the home of the Yorks throughout the 1790s, though they removed themselves to Weybridge in 1798 while it was

Our Fete was, however, only one such ball in a packed programme of similar events; The Evening Mail (22nd May 1799) reported on recent balls hosted by the Queen and by the Duke of Cumberland, then added that

The terms

Description of the FeteOur Fete was probably held on Thursday the 29th May 1799 (the accounts differ on the precise date of the event), it was unfortunately a rainy day, many of the open air plans had to be abandoned. Numerous newspapers, in varying detail, carried descriptions of the gathering, one of the first was The Times (1st June 1799) which simply wrote: In defiance of the rain, the Duchess of York's Fete at Oatlands on Thursday was splendid in the extreme. The Royal Family dined in the new apartment, called the Green Room, adjoining to which was the Ball Room; fronting the Thames on the lawn, six Marquees were erected, communicating to each other, where tables were spread for the Nobility. The dinner was served at three o'clock. On the table where the Royal Family were seated was a dish of green pease. During the Dinner, the Duke's band performed martial airs. After the Dessert, the company repaired to the Ball Room. Country Dances were led down by the Duke of Kent and Princess Augusta, to Scotch airs; and continued till eight in the evening; and at ten their Majesties and most of the company took leave of the Royal Highnesses.  Figure 2. Oatlands House seen from the direction of the River Thames. Image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 2. Oatlands House seen from the direction of the River Thames. Image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

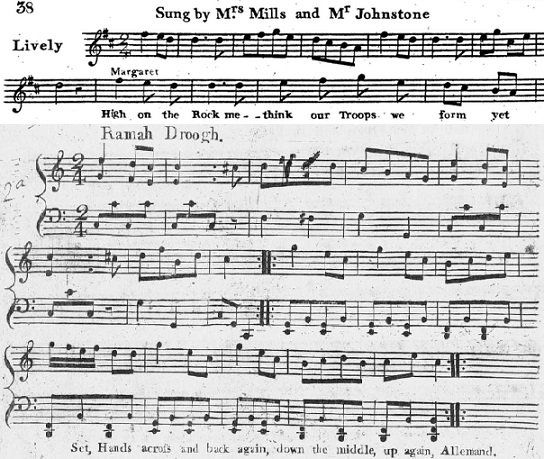

A slightly different angle (and date) was offered by the Salisbury and Winchester Journal a couple of days later (3rd June 1799), several of the incidental details differed: Yesterday the Fete given by the Duke and Duchess of York, to their Majesties &c. at Oatlands, proved a very splendid entertainment; but theal frescopart of the plan, for which the most elegantChampetredecorations had been arranged, was unfortunately prevented by the showery weather. The King, Queen, and Princesses arrived soon after two, where the Prince, and the Dukes of Clarence, Cumberland, Kent, and Gloucester, the Stadtholder, Princess of Orange, and the Foreign Ambassadors, Mr Pitt, Mr Dundas, and a large assemblage of the principal Nobility of both sexes, were assembled, with their Royal Hosts, in the new Saloon, to receive them, while a band of wind instruments were playing military music in the hall. About three, the company sat down to an elegant collation, and in the evening there was a brilliant Ball. The Majesties and the Princesses returned to the Queen's House, about half after eleven last night. For the details of the dancing we'll turn to the Kentish Gazette (4th June 1799), dance references have been highlighted: The day was most unfavourable to this magnificent Fete. It rained the whole day, and all the brilliancy of that part of the entertainment which depended on the weather was lost. Six tents, all corresponding with each other, were erected on the lawns, in which dinner was served to one hundred and sixty of the principal Nobility. The Royal party dined in the Conservatory, and they sat down twenty in number. The Princess of Wales was not present. The wetness of the day not merely made the tents uncomfortable, but the decorations of confectionary were damped on the tables. Nothing could be more superb than the plan of the fete. Though the entertainment was a moderndejeune, the whole was in the stile of an ancient dinner, and both the Ladies and Gentlemen were full drest. The Invitations were confined to the highest order of the Nobility, and the whole was conducted with attention to the most perfect rules of etiquette, the company taking their places according to precedence.  Figure 3. The start of a song from the 1798 Ramah Droog (top), and the Ramah Droogh country dance from George Kauntze's c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes &c..

Figure 3. The start of a song from the 1798 Ramah Droog (top), and the Ramah Droogh country dance from George Kauntze's c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes &c..

Most of the dancing evidently followed a Scottish theme, with a notable Reel of Four being displayed; strict rules of courtly precedence were followed for the dancing with couples taking their place based on their relative rank. Next we'll consider each of the named dances in turn.

Ramah DroogThe Princess Augusta and the Duke of Kent led the two first dances...The first dance was Ramah Droog, Ramah Droog; or Wine Does Wonders was the name of a comic opera by James Cobb that was performed at Covent Garden theatre between late 1798 and early 1800, the associated music was composed by Joseph Mazzinghi and William Reeve - the score is available through Google Books, as is the libretto. The plot involved an adventure in British controlled India; an usurper had risen up and a British military detachment was captured, but after suitable heroics, a little cross dressing and a surprise hangover, the British carried the day. The name Ramah Droog referred to a fortress somewhere in India. Our country dancing tune of the same name was almost certainly derived from the music of the stage production; the Royal family were reported to have watched Ramah Droog at Covent Garden in late 1798 (The Observer, 2nd December 1798).

At least two country dancing tunes named Ramah Droog were published in London c.1800, though one was more widely issued by the music sellers; it's probable that it was this popular variant that was danced at our Fete in 1799. This particular tune was derived from an unnamed song from the opera that was described as being This dance was led off by Princess Augusta and the Duke of Kent. Augusta was the older sister of the King and also the mother-in-law of the Prince of Wales; Prince George and his wife Princess Caroline of Brunswick (the daughter of Princess Augusta) were somewhat estranged at this 1799 date, we're told that Caroline did not attend this Fete. Augusta, as the senior Aunt, and on an occasion where strict rules of precedence were being observed, was invited to commence the dancing. Her partner for this dance was Prince Edward (another brother to the Prince of Wales and our host the Duke of York), he had recently returned from the Americas and had been appointed Duke of Kent only a month prior to our Fete; Edward, 20 years later, would go on to father the future Queen Victoria. I've not encountered references to the tune being used for Country Dancing at any other social events, though it's likely to have been relatively popular after having received Royal patronage at our Fete. The opera remained known into the 1820s and beyond. This was the opening dance of the evening Ball and it's the only tune with no obvious connection to Scotland; adapting popular stage tunes into country dances was a common practice, many of the most successful tunes were borrowed from the stage. This particular tune had a patriotic theme that was likely to resonate, it may have been used in honour of the Duke of Kent who was being celebrated as a war hero. We've animated suggested arrangements of the c.1799 Kauntze version (see Figure 3) and the c.1800 Campbell version.

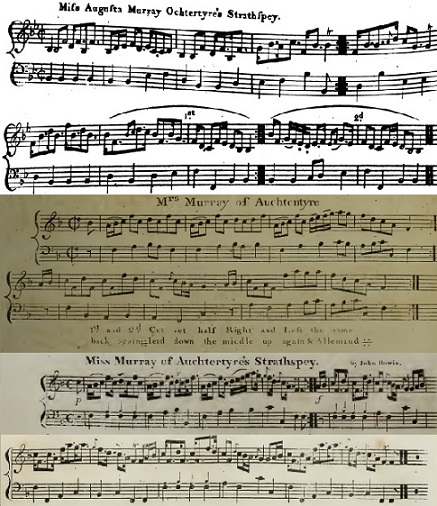

Miss Murray of Auchtentyre's Strathspey... second Miss Murray of Auchentire.  Figure 4. John Bowie's c.1797 Miss Augusta Murray Ochtertyre's Strathspey from Four New Tunes (top); William Campbell's Mrs Murray of Auchtentyre from his c.1797 12th Book (centre); Gow's c.1799 Miss Murray of Auchtertyre's Strathspey (credited to John Bowie) from Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances (bottom).

Figure 4. John Bowie's c.1797 Miss Augusta Murray Ochtertyre's Strathspey from Four New Tunes (top); William Campbell's Mrs Murray of Auchtentyre from his c.1797 12th Book (centre); Gow's c.1799 Miss Murray of Auchtertyre's Strathspey (credited to John Bowie) from Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances (bottom).

Numerous different tunes were circulating around the end of the 18th Century which might perhaps be candidates for the tune danced at our Fete, but one particular candidate was widely published c.1800, it was clearly the popular tune; but as we'll see, even this popular tune is subject to significant confusion spanning its title, provenance, and even touching upon a Royal scandal!

Credit for composing the popular tune was ascribed to (and also claimed by) John Bowie of Perthshire. Bowie published at least four collections of dance tunes that he'd composed himself; he issued a large collection of Reels and Strathspeys c.1789, a collection of four new tunes c.1797, a collection of six and a further short collection of tunes c.1801. I've studied the first three collections, none of them contain our tune; the final c.1801 collection may have contained it, but Bowie described himself when advertising it as

The tune was published several times in London between 1797 and 1799, the first Scottish publication I can confirm was that of the Gows, they included it in their c.1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances under the name Miss Murray of Auchtertyre's Strathspey, they explicitly credited composition to Bowie (see Figure 4, bottom). Bowie himself had published a tune named Miss Augusta Murray Ochtertyre's Strathspey in his c.1797 collection of Four New Tunes (see Figure 4, top), but that tune was entirely different to the tune published by Gow, despite closely matching the name that Bowie himself claimed to be

The very first publication of the popular tune that I can identify was that of William Campbell in London, it was part of his c.1797 12th Book, issued under the name Mrs Murray of Auchtentyre (see Figure 4, centre). It's unlikely that Campbell was the composer as he invariably claimed credit for his own compositions, many of the tunes he issued were first published in Edinburgh so it's likely to have previously circulated there before he published it. Campbell named the tune for Before considering the Royal scandal we should first consider another curious publication of the tune. I'm indepted to Alena Shmakova for pointing out that our tune can also be found in an Edinburgh publication published by N. Stewart named The South Fencible's March. This work is challenging to date, my best guess is that it dates somewhere between 1796 and 1800; as such it could have been Campbell's direct source for the tune... or it could have been published after the tune became successful in London. The British Library date Stewart's publication to the year 1800.

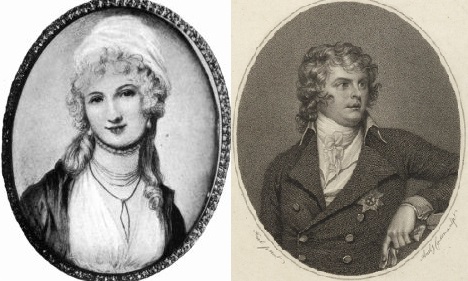

The King's 6th son was Prince Augustus Frederick (1773-1843, see Figure 5), he would later become the Duke of Sussex; he had secretly married Lady Augusta Murray of Dunmore (1768-1830) in 1793, contrary to the wishes of his father and illegally under the terms of the 1772 Royal Marriages Act. His older Brother Prince George the Prince of Wales had done the same thing with Mrs Fitzherbert in 1785, and in both cases the marriages were legally dissolved by the King. The marriage of Augustus and Augusta was formally annulled in 1794 and Lady Augusta Murray was left to raise their son alone. The couple did briefly reunite later in 1799 resulting in a second illegitimate child, followed by a permanent separation. It's possible that Campbell, or some other agent in London, had modified the name of our tune to avoid any implied dedication to the Prince's unofficial bride;  Figure 5. Lady Augusta Murray (left) and Prince Augustus Frederick (right); right image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 5. Lady Augusta Murray (left) and Prince Augustus Frederick (right); right image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

This does raise the intriguing question of why the tune featured so prominently in our Fete of 1799. Surely there was no intended reference to Lady Augusta Murray... but perhaps someone was manipulating events? Was the tune perhaps introduced as a joke? It's unclear (to me) whether Prince Augustus was even in England at our date in 1799, he had been staying in Naples but he had been recalled to London and may have arrived in time to attend our Fete; it's curious that within a few months of the date of our Fete the couple were reunited. Perhaps the Prince of Wales himself championed the tune as a sly prank at the expense of his parents, a cabal of intimates may have been aware that the tune was known by more than one name, and that the original dedicatee may have been named A further anomaly can be found in the tune having yet another name; the Preston publishing company issued it under the name Lady Portmores Reel in their collection of 24 Country Dances for 1800. The last Lady Portmore died in early 1799; there's probably no significance to their name, but it's possible that it was a yet older name for the tune. The tune was may have been composed by Bowie and it might have been dedicated to a Miss Augusta Murray, the evidence seems uncertain; but it certainly was published many times in both London (c.1797-1805) and Edinburgh (c.1799-1805); it was indisputably a popular tune. It remained sufficiently relevant for Thomas Wilson to include suggested figures for the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore, though references thereafter are harder to find. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Wilson's 1809 figures for Mrs Murray to Gow's c.1799 music (composition of which was credited to John Bowie, see Figure 4 bottom), and of William Campbell's c.1797 version (see Figure 4, centre). For futher references to the tune, see also: Miss Murray of Auchtertyre's Strathspey at The Traditional Tune Archive

Reel of FourBetween the second and third dance, their Majesties desiring to see the Highland Reel danced in its genuine purity, a reel was danced by the Marquis of Huntley and Lady Georgina Gordon, Colonel Erskine, and Lady Charlotte Durham, in which they displayed all the elastic motion, hereditary character, and boundless variety of the Scotch dance.

The Reel was a form of dancing particularly associated with Scotland; the music for a Reel is often compatible with that of a typical Country Dance and the dancing involves a mixture of weaving and setting (also known as

The dance might sound simple, but it can be exhausting to dance; the skill is in the fancy stepping, graceful use of the arms, the snapping of fingers, and the whooping and other vocal gymnastics; or, as our correspondent put it, in the  Figure 6. Highland Reel, 1798 (left), and the track of a Reel of Four (right). Left image courtesy of the British Museum, right image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Note the dripping candle wax, the enthusiastic dog and the ladies holding fans.

Figure 6. Highland Reel, 1798 (left), and the track of a Reel of Four (right). Left image courtesy of the British Museum, right image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Note the dripping candle wax, the enthusiastic dog and the ladies holding fans.

On this occasion the King requested that a Reel be danced, several members of the Scottish nobility obliged. The Marquis of Huntly was the first of the party, he was George Gordon (1770-1836) son of the Duke and Duchess of Gordon, he would later become the 5th Duke; George's youngest sister Lady Georgiana Gordon (1781-1853) was the second member of the party, she would go on to become the Duchess of Bedford. Their mother, Lady Jane, Duchess of Gordon was a great favourite of the Prince of Wales, she was credited with promoting Scottish culture in London, and notably Scottish music and dancing. The Marquis was evidently a favourite of the Queen, he led down the two dances following this Reel with her. The third of the dancers was Colonel Erskine (1770-1813), later Major-General Erskine, 2nd Baronet Erskine; the fourth was Lady Charlotte Durham (1771-1816), a recently married daughter of the Earl of Elgin. They evidently performed well; most of the dances at our Ball were Country Dances and would have been danced for the enjoyment of the dancers themselves, whereas this Reel of Four was performed to impress an audience (somewhat like the performance of a courtly Minuet, though in a very different style). The entire event was conducted on a Scottish theme, the inclusion of a Reel would have been highly suitable to the occasion.

Occasional references to the Reel being danced in England exist from at least as early as the 1760s, particularly on stage in Allan Ramsay's The Gentle Shepherd and similar (e.g. Newcastle Courant, 23rd July 1763). Mr Wood, a dancing master from Halifax, advertised that he taught the Reel in 1778 (Manchester Mercury, 6th January 1778); other northern dancing masters began doing so from a similar date. Several London based dancing masters advertised tuition in the Reel from around 1789 (including Mr Wilson, Wills, Jenkins, Le Pulley, etc.); Alexander Wills, for example, advertised that he taught

The popularity of the Reel in London may have grown alongside that of the

The Aberdeen based dancing master Francis Peacock published his Sketches Relative to the History and Theory, but more especially to the Practice of Dancing in 1805, he wrote extensively on the Reel, including detailed information about the steps that might be used. He included an anecdote of London based dancing masters travelling to Edinburgh for tuition in the steps:

The transmission of dance culture wasn't simply in a single direction however, dancing masters from Edinburgh also adopted the various innovations in

The London based dancing master Thomas Wilson also wrote about how to dance the Reel. The final form of his instructions can be found within his c.1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing, a work that had been evolving across the 1810s. Wilson began by describing The Reel would go on to be an important dance in the ballrooms of London's aristocracy over the 15 or 20 years following our Fete. The Reel had grown in significance over several decades, promoted by the members of the Highland Society amongst others, 1799 marked the start of its particular popularity in London. Reels would often be danced towards the end of a society ball of the 1800s or 1810s, a time when many of the company were tiring and only the most enthusiastic of dancers would remain active. Our Fete of 1799 may have been influential in promoting the dance, it would go on to be danced in fashionable assemblies around the country.

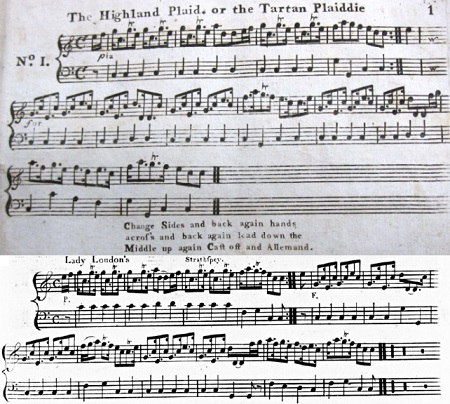

Tartan Plaiddie / Highland Plaiddie / Lady Loudon's StrathspeyThird, The Tartan Pladie, or Lady Lowdon's Strathspey Numerous tunes with names that were minor variations on Tartan Pladdie circulated in the late 18th century, at least a half dozen candidates are readily available; our correspondent has helpfully disambiguated the tune from the Ball by providing the alternative title of Lady Lowdon's Strathspey. This particular tune was widely published in both London and Edinburgh from around the year 1788. The composer of the tune was probably William Gow, Nathaniel Gow credited William (his Brother) as the composer in his 1818 Part First of The Beauties of Niel Gow; the tune had previously been included in Niel Gow's 1788 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. without a composition credit (see Figure 7).  Figure 7. The Highland Plaid, or the Tartan Plaiddie from William Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (above), and Lady Loudon's Strathspey from Niel Gow's c.1788 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels, etc. (below). Upper image courtesy of Cardiff University.

Figure 7. The Highland Plaid, or the Tartan Plaiddie from William Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (above), and Lady Loudon's Strathspey from Niel Gow's c.1788 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels, etc. (below). Upper image courtesy of Cardiff University.

The Gows published the tune in Edinburgh as Lady Loudon's Strathspey, but it was also published in London as The Highland Plaid or the Tartan Plaiddie in William Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book (see Figure 7). The precise chronology of publication is uncertain, Campbell sourced many of his tunes from Edinburgh so it's likely that the Gow publication was issued first; if so, Campbell didn't retain the original name for the tune. His new name of Tartan Plaiddie was already established in London, it was associated with a popular song from a comic opera also named Tartan Plaiddie (the music for which was credited to James Hook) that circulated in 1787. It's possible that Campbell simply picked the name Tartan Pladdie as the title was already known; it's also possible that the Gow tune was used within the stage production without credit, or perhaps even that the Gow claim was erroneous. The tune was evidently popular as it remained in print into the early 19th Century. Other early publications of the tune in London include Thomas Jones's 1789 Ten new Country Dances & three Cotillons and Longman & Broderip's c.1791 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c. (their version was copied from Campbell's publication verbatim, despite their having acted as the publisher for Jones' edition a couple of years earlier). Joseph Dale issued it in his c.1799 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels &c. (Dale's version was copied verbatim from Longman & Broderip, just as their version had been copied from Campbell). The tune was also available in Preston's early 1790s Selection of the most favorite Country-Dances, Reels &c., the precise publication date of which remains uncertain; also as The Highland Plaid in Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys. The London publications of the tune invariably used some variation of Campbell's name, typically The Tartan Plaiddie. The tune was also published multiple times in Scotland; it can be found in John Anderson's c.1789 A Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys, Country Dances, English & French Dances, and in the c.1794 Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol IV that was issued by John McFadyen in Glasgow and is usually credited to James Aird. The Scottish publications retain the original name of Lady Loudon's Strathspey.

The name The inclusion of the tune in this Scottish themed Ball was clearly highly suitable; it was already an old tune by our 1799 date, but despite having circulated for over a decade it was selected and enjoyed. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's c.1788 version of the dance (see Figure 7), and also of Thomas Jones's 1789 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Loudon at The Traditional Tune Archive

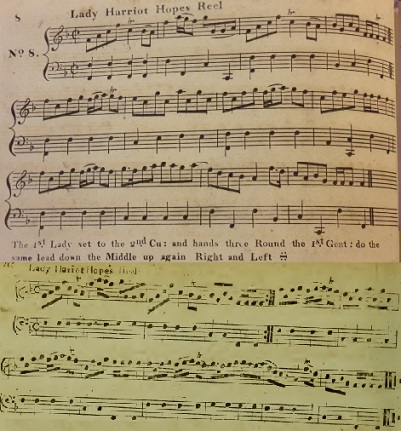

Lady Harriot Hope's Reel... fourth Lady Harriot Hope's Reel.  Figure 8. Lady Harriot Hopes Reel from Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favorite Country Dances (above), and from Bremner's c.1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.e.(5.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 8. Lady Harriot Hopes Reel from Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favorite Country Dances (above), and from Bremner's c.1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.e.(5.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

This tune was published a great many times in both London and Edinburgh, it was clearly an enduring favourite. The earliest publication was probably in 1757 as part of A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances issued in Edinburgh by Robert Bremner (see Figure 8), Bremner's volume was subsequently republished in London in the early 1760s. Thereafter it was published in London in the c.1772 third volume of Rutherford's Compleat Collection of the most celebrated Country Dances and in Thompson's c.1789 Caledonian Muse. It appeared again in Joseph Dale's c.1804 3rd Number, in William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and in Charles Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favorite Country Dances (see Figure 8). Thomas Wilson referenced the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and also printed the music in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. The tune can also be found in both the Goulding and Davie collections of the early 1800s (though I can't provide precise dates of publication). Scottish publications of the tune include James Aird's c.1783 A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, volume 2, John Anderson's c.1789 A Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys, Country Dances, English & French Dances, Robert Petrie's 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels (and then again in his 1799 Third Collection) and Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances.

The identity of the dedicatee, Lady Harriot Hope, isn't entirely obvious, though two strong candidates emerge. The first identification is with

This tune did feature in several royal balls around the turn of the 19th century; for example, it was used at the King's Birthday Ball a few days after our Fete, the Evening Mail (3rd June, 1799) reported We've animated suggested arrangements of Wheatstone's 1806 version (see Figure 8), and one of Thomas Wilson's 1809 arrangements to the Goulding music. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Harriet Hope (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

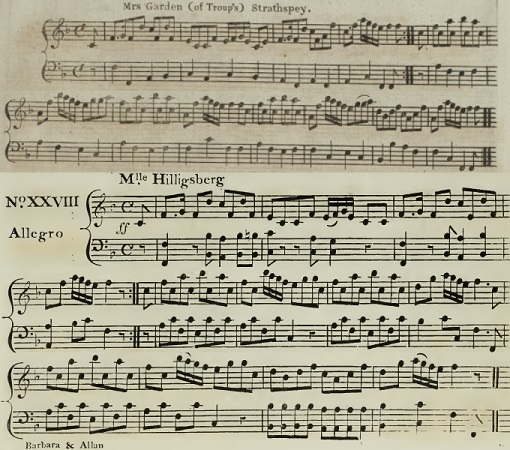

Mrs Garden of Troup's StrathspeyAfter a short interval, in which the company took tea, the ball recommenced, and the entertaining tune of Mrs Garden of Troup's Strathspey, called by the Princess Augusta, was danced twice over by all the set. This tune, requested by Princess Augusta was very popular around the start of the 19th Century; it was composed by Robert Petrie and published in Edinburgh in his 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. (see Figure 9). Petrie worked for the Garden family of Troup House, he dedicated this tune (and also the whole book) to his employer's wife.

The tune was first published in 1796, by 1799 it would appear in several further collections issued in both Edinburgh and London. It was issued in Edinburgh in Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances (on the same page as Lady Harriot Hope and immediately after Miss Murray of Auchtertyre's Strathspey), in Nathaniel Gow's c.1800 Miss Heron of Heron's Reel publication (where it was described as having been  Figure 9. Mrs Garden (of Troup's) Strathspey from Robert Petrie's 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (above), and the Scotch Air from J.H. D'Egville's 1801 Barbara & Allen (below). Upper image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

Figure 9. Mrs Garden (of Troup's) Strathspey from Robert Petrie's 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (above), and the Scotch Air from J.H. D'Egville's 1801 Barbara & Allen (below). Upper image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

Identifying the dedicatee, Mrs Garden of Troup, is a little complicated. The Garden family of Troup House in Banffshire were particularly fond of the names

The tune was probably danced to at several royal balls at around the turn of the century; a tune named Garden of Troop's Reel (note The tune of Mrs Garden of Troup's Strathspey remained popular in London through to about 1807 under a new name and with a new composition credit. James Harvey D'Egville was credited as the composer of the 1801 pastoral ballet of Barbara and Allen, one of the acts involved a Scottish themed dance performed on stage by Miss Hilligsberg, the music for which was our tune of Mrs Garden of Troup's Strathspey (although uncredited as such, see Figure 9). It's unclear whether D'Egville was deliberately appropriating credit for the tune, it was after all a well known tune at that date and the duplication was likely to be recognised. He may have simply used the tune believing that country dancing music was implicitly of common ownership, and not subject to copyright protection; it would take another 15 or so years for that legal theory to be proven wrong. The Cahusacs published the tune in their collection of 24 Country Dances for 1802 under the name Barbara & Allen; whereas Goulding & Co. (and the publishers who copied from them) issued the same tune as Mrs Garden of Troop, or Barbara & Allen in their c.1805 7th Number. John Baptist Cramer even published a Rondo arrangement of the Scotch Air from Barbara & Allen in 1801 (Morning Post, 5th November 1801), he may have done so whilst remaining oblivious to the true origins of the tune.

We're informed that the tune was so popular at our Oatlands Fete that it was We've animated suggested arrangements of the Cahusac version for 1800 and the Preston version for 1800. For futher references to the tune, see also: Mrs. Garden of Troup (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

ConclusionThis event may have been conducted with formal rules of precedence but it was evidently enjoyed by the attendees, without undue ceremony. A Reel of Four was demonstrated and the final dance was performed twice through, this was despite the unfortunate rain that had spoiled so many of the carefully made plans. The theme of the event was predominantly Scottish, but not exclusively so. We're not told who led the band at the Fete. It's likely that at least one of the London based Gow brothers was present in some capacity (either Andrew or John) as someone sent timely information back to Edinburgh, not just for this ball, but for all the Scottish tunes that were becoming popular in London. Nathaniel Gow edited Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances, by Niel Gow & Sons in Edinburgh, the book was advertised for sale from August 1799 and it included the tunes from our Ball in clear consecutive order. That seems unlikely to be coincidental, Nathaniel was taking care to include the popular-in-London Scottish tunes in his publication; perhaps he was in London himself at our date. The Gows were influential in promoting Scottish tunes in London over the following couple of decades; at our 1799 date they seem to have been printing Scottish tunes in-arrears after they were already successful in London, they would soon be ahead of the trend and would publish the Scottish tunes in Edinburgh that would go on to become successful in London. The Gow band would become synonymous with Scottish dancing in London and every hostess would aspire to hire the Gow band for her ball; if they were present at our 1799 Fete then that event may have been significant in promoting their services. This ball was not the first in London to feature a performance of the Reel, but it is the best documented of those that did. This Fete may have been especially influential in promoting the Reel in London, it is certainly evidence of the growing popularity of the Reel and of Scottish themed dancing in general. If you'd like to recreate a Fete of 1799 then the tunes we've identified in this paper are clearly suitable for use, especially if you're interested in a Scottish theme; but we'll leave this investigation here, if you'd like to Contact Us with further information then we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved