| Return to Index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paper 47 British Dance Fans, 1789-1822Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 4th November 2020, Last Changed - 31st March 2024]

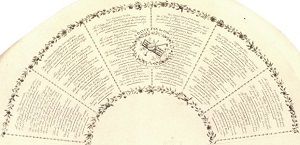

Hand fans were an essential accessory to the Ball Room of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In this paper we'll consider their purpose and investigate the phenomenon of  Figure 1. Edward Payne's 1817 Quadrille Fan

Figure 1. Edward Payne's 1817 Quadrille Fan

The Myth of a

|

| Details | Contents |

|---|---|

| Eighteen of the Most Favourite Country Dances,

with their proper figures adapted to each as performed at Court, Bath, &c., 1789 [advertised by L. Sudlow in December 1789]  |

The Bastille [probably also in Prestons's 24 Country Dances for 1790],

La Malbro [also in Budd's 12th Book for 1784], The White Cockade [also in Campbell's c.1788 3rd Book], Theodore [also in Werner's 16th Book for 1783 where it is arranged as a Cotillion], What a Beau your Granny Was [also in Thompson's c.1790 12 New Cotillions and 12 Country Dances], New German Spa [also in Budd's 13th Book for 1784], La Belle Catherine [also in Werner's 18th Book for 1785], Mrs Casey [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1788], Poor Jack [probably also in Prestons's 24 Country Dances for 1790], Patty Clover [probably also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1789], Union Dance, Lady Charles Spencer's Fancy [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1779], Nottingham Races [also in Thompson's c.1780 Compleat Collection, volume 4], Tartan Pladdie [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1788], La Fete de Village [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1778], Capt Mackintosh's Fancy [probably also in Prestons's 24 Country Dances for 1789], Astley's Hornpipe [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1785], Money Musk [also in Werner's 18th Book for 1785] As the title suggests, these genuinely were some of the most favourite country dances at the time of publication, most are known from several other sources. |

| Fourteen new Country Dances for 1791,

with their proper figures as performed at Court, Bath, and all polite Assemblies, 1790 [advertised by E. Sudlow in December 1790]  |

Revolution de la France,

The British Flag, The Westminster Election, Amazonian Archers, No Taxes, The New Parliament, The Greenwich Pensioner, The Shrubery, Bucks of Europa, The Triple Alliance, The Ultimatum, Baroness Nagel's Fancy, The Target As the title suggests, these dances seem to have genuinely been new. They may have been composed and arranged specifically for publication on this fan. If so, it's unclear how musicians would be expected to perform the tunes; if someone called for such a tune then it wouldn't already be known. |

| Eighteen of the Most Favourite New Country Dances, c.1791 [probably late 1790 or early 1791]  |

Duke of Clarence's Fancy [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures],

The Harriot [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1787, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Payne's Jigg, Dibdin's Fancy [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Whim of the Moment [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures], Sir Alexander Don, Duncan Gray [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1790], The Haunted Tower [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Waltz [also in Longman & Broderip's 18 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], The Birth Day [also in Longman & Broderip's 18 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Kiss me Sweetly [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1790, with slightly different figures], Dreary Dun [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1790, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Captain McLean [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1790, with slightly different figures and minor changes to the score], Jem of Aberdeen [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1790], Miss Dykes Fancy, The Highland Club, Garthland [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1790], The Fife Hunt [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791, with slightly different figures]

Most of the content for this fan is derived from publications that were issued around the end of 1790 (that is, |

| Ten Country Dances, Four Strathspeys, And Four Reels, For The Year 1792, c.1792 [probably late 1791 or early 1792]  |

Morgan Ratler [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1790],

Money in both Pockets [known from many sources], The Welch Dance [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Tippoo Saib [possibly from Smart's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Maggie Lawder [possibly from Smart's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Duchess of York's Fancy or the Prussian, Cymro'blee or the Welch Question [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], The Siege of Belgrade [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Prince of Wales's Fancy [possibly from Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Lady Catherine Stewert's Fancy [probably from Smart's 24 Country Dances for 1791], Lady Loudon's Strathspey [also in Anderson's c.1789 Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys], Mrs Donaldson's Strathspey [also in Anderson's c.1789 Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys], Mrs Baird of Newbyth's Strathspey, Duchess of Gordon's Strathspey [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791], Jenny Sutton's Reel [probably from Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1791], The Edinburgh Castle Reel [probably from Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1791], The Gloster Reel [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Sir Alexr Don's Reel [probably from Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1791] Most of the Country Dances on this fan were very well known and were genuinely popular; the Strathspey tunes are curious as they omit any suggested dancing figures. In several cases the direct source of the dance (both the tune and figures) can be identified. |

| Princess Frederica Fan #1, c.1791  |

The Royal Flight [also in Cahusac's 12 for 1792],

Margate Assembly [also in Preston's 24 for 1792], Shuter's Hornpipe, The Prussian [also in Cahusac's 12 for 1792], Miss Bentick's Fancy [also in Cahusac's 12 for 1792], Pauvre Madelor [also in Preston's 24 for 1792], Duchess of York's Fancy, Money in both Pockets [also in Cahusac's 12 for 1792], Ca Ira [also in Thompson's 24 for 1792], The Russian Tippet [also in Preston's 24 for 1792], Miss Rowly's Fancy [also in Cahusac's 12 for 1792], Champ Mars [also in Thompson's 24 for 1792], The happy Lass [also in Preston's 24 for 1792] Most of the tunes in this collection were issued |

| Princess Frederica Fan #2, December 1791 [the date is on the fan]  |

No Song No Supper [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792],

Tippoo's Defeat [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Duchess of York's Fancy, The Russian War [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], The New Year's Gift [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Datchet Bridge [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Tippoo Saib [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Le Champs de Mars [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Caen Wood Dance [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Pauvre Madelor [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Cupid's Frolic [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1792], The Surrender of Calais [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], The Masked Rout [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1792], The Welch Question [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792], Prussian Marriage, The Welch Dance [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1792] Most of the tunes in this collection were issued |

| Ten of the most favorite Country Dances & Five Cotillons, March 1793 [issued by John Cock & Crowder, the date is on the fan]  |

La Malbro [also in Budd's 12th Book for 1784],

New German Spa [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1786], Money Musk [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1786], What a Beau your Granny was [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1789], The Bastille [perhaps in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1790], The White Cockade [perhaps in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1790], Mrs Casey [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1788], Captn Mackintosh's Fancy [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1789], The Storace or Gamon's Frolick [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1789], Astley's Hornpipe [also in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1784], Vouz Lordonnez, La Belle Jeannette, La Dame Francaise, L'Amour Fidelle, The Monaco The Country Dances on this fan seem to have been genuinely popular tunes that had been in circulation for much of the preceding decade, most are known from many sources. The five cotillions (listed last) are harder to source; some of the tunes are known from other sources but the origin of the figures remain to be discovered. A message on the fan reveals that it was published on the 1st of March 1793. |

| The New Caricature Dance Fan, November 1793 [issued by Stokes, Scott & Croskey, the date is on the fan]  |

O Dear what can the Matter be [also in Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1794],

Duke of York at Valenciennes, Duchess of Gordon's Reel [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Royal Meeting [probably in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1794], Prince Apolphus Fancy [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Primrose Girl [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], Trip to Margate [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Musicians Flight to America [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Sprigs of Laurel [probably in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Pad, The Duke of York's Fancy [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], Trip to Dunkirk, Little Farthing Rushlight [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794, with minor differences], Brighton Review [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794]

A message on the fan reads |

| New Country Dances for the Year 1794, c.1794  |

Miss Stewart's Reel,

The Hop Ground [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Duke of York's Fancy [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Royal Kentish Bowman [I have seen another exact match of this dance in an unidentified c.1794 collection], Oscar & Malvina [perhaps in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1793], The Prussian Festival, The Princes Fancy, Lady Shaftesbury's Fancy, Lady C. Campbell's Reel [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Sprig of Laurel [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], The Mountaineers, Miss Sutherland's Reel, The Children in the Wood, Lord McDonald's Fancy [also in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1794], Plymton's Delight [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1794] The copy of this fan leaf that I've studied had never been cut, instead a fan mount was painted around it; what survives today is arguably a painting. This fan is probably the fan advertised by S. Ashton in 1794 (The Times, 28th February 1794) but as no manufacturer's mark can be seen the fan's identity is uncertain. |

| The New Dance Fan for 1797, November 1796 [the date is on the fan]  |

Miss Stewart Senton's Reel,

Miss Douglas Brighton's Jigg, Countess of Sutherland's Reel [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1797], Mr Oliphant of Condie's Strathspey [music available in Bowie's 1789 Collection of Strathspey Reels], Honble Charles Bruce's Reel [music available in Bowie's 1789 Collection of Strathspey Reels], Little Peggy's Love, Fontainblau Races [music available in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1787] Miss Biggar's Strathspey [music available in Bowie's 1789 Collection of Strathspey Reels], The Irish Volunteers [perhaps in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1785] Watson's Reel, Miss Smith's Delight, A Trip to Glasgow, Wedderburn's Reel, Leap Year [perhaps in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1793] Galloway House [music available in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1787] Davy's Locker [also in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1797] A message on the fan reveals that it was published on the 1st of November 1796. The content is unusual as the tunes, in most cases, aren't known to have been popular, nor were many of them new for 1797. The content appears more random than usual. |

| A Dance Fan for 1798, c.1798 [issued by S. Ashton & Co]  |

The Brunswick [music available in Campbell's 1795 10th Book]

The Fisher's Hornpipe [music available under many names from many sources, eg Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1790 as Blanchard's Hornpipe] Lord Hume's Reel [music available in Hime's Country Dances for 1799] Del Caro's Hornpipe [music available in Longman & Broderip's c.1795 5th Selection] Drops of Brandy [music available in Campbell's c.1796 11th Book] The Chosen Few, or The Rowing Match [music available in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1795] The Village Maid [music available in Campbell's c.1786 1st Book] Miss Bentick's Fancy [music available in Campbell's c.1791 6th Book] The Royal Quick Step [music available in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1796] The Isle of Skie [music available in Campbell's c.1792 7th Book] Dusty Miller [music available in Campbell's 1795 10th Book] New German Waltz [music available in Campbell's 1795 10th Book] Lads of Dunce [music available in Thompson's c.1765 2nd Volume of 200] Ask Again [music available in Feuillade's 4 New Minuets, etc. for 1782] Bonny Lads [music available in Goulding's 24 Country Dances for 1797] Jenny's Baubee [music available in Campbell's c.1794 9th Book] Pr. Edward's Fancy [music available in Campbell's c.1793 8th Book] The Merry Wives of Windsor [music available in Smart's c.1798 Collection of New & Favorite Country Dances] Coll Mackay's Reel [also in Campbell's 1795 10th Book] Ally Croaker [music available in Campbell's c.1794 9th Book] St Bride's Bells [music available in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1755] Savage Dance [music available in Werner's 1784 17th Book] Duke of Glocester's Reel [music available in Campbell's 1795 10th Book] Light and Airy [music available in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1766] Marquis of Huntley's Highland Fling [music available in Jenkin's 1797 New Scotch Music] Lord Macdonald's Reel [music available in Campbell's c.1793 8th Book] Mogg at the Wadd [probably Moll in the Wadd, music for which is available in Campbell's c.1797 12th Book] Cosby's Delight Blanchard's Reel Swaffham Dance Taffy's Fancy Pr. Willm of Glocester's Favourite [also in Campbell's 1795 10th Book] Cumberland Reel [music available in Campbell's c.1791 6th Book] Jack Latten [music available in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1791] Coll Macbean's Reel [music available in Longman & Broderip's 24 Country Dances for 1789] The dances named on this fan lack any music, they only have a list of suggested figures. They were mostly well known tunes that professional musicians would have been expected to know. Most of these tunes are known from multiple collections of the period. Indeed, this fan is unusual in that most of the named tunes were very well known; a customer who purchased this fan might have a reasonable expectation of enjoying a successful dance calling experience (the same is much less true for any of the other fans). In most cases I can't identify the specific source of the figures, they may have been choreographed specifically for this fan. It's curious that many of the tunes had been in circulation for several years, presumably they retained popularity, there's no suggestion that they were new for 1798. |

| The New Egyptian Dance Fan for 1799, c.1798 [probably late 1798 or early 1799]  |

British Navy New Reel, or Nelson's Fancy thro the Nile [probably also in Norman's 24 Country Dances for 1799],

A Trip to Alexandria [also in Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1799], General Lake's Waltz [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Royal Volunteers [also in Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Croppies Lie down [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], London Beauties [also in Rolfe's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Toulon Fleet, Sweating Doctor, Scotch Fencibles [also in Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Gipsey Hat [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Sir Sidney Smith's Escape, Little Patty [also in Rolfe's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Windsor Camp [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Turkish Allmand [probably also in Norman's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Target Reel [probably also in Norman's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Village Hop [also in Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1799], The Stranger, Buonaparte's Expedition [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Knight's of Malta [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Irish Invasion [also in Skillern's 24 Country Dances for 1799] This Fan borrowed heavily from dance collections published in London |

| Nelson & Victory 18 new Country Dances for 1799, c.1798 [probably late 1798 or early 1799]  |

North Sea Fleet [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799],

Margravine's Waltz [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Paddy O'Boderam [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Croppies lie Down [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Greenwich Ball, Pas Russe or the Russian Dance [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Fantocinis[?] Hornpipe, Military Fete [music available in Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Sprigs of Laurel for Admiral Nelson [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Ladies down the Middle[?], Blue Beard [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Scotch Milita Reel [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Diddelot Reel [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Straw Bonnet [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Miss Stuarts Reel [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Lord Duncans Reel [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Drops of Whiskey [music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799], Irish Devil [this tune is better known as Go to the Devil and Shake Yourselfor Bow Vow, music available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1799]

The image of this fan that I've worked with is unclear, a few of the titles are particularly difficult to read and may have been transcribed incorrectly. What's clear is that the vast bulk of the content derives from the Preston collection of Country Dances for 1799. A message on the fan reads |

| Country Dance Fan for 1802, c.1802 [probably late 1801 or early 1802]  |

The image of this fan that I've worked with is too small to transcribe. It evidently has music and figures for 16 dances on it. |

| Country Dance Fan for 1803, c.1803 [probably late 1802 or early 1803]  |

Mr Otto's Whim [also available in Thomson's 24 Country Dances for 1803]

A Trip to the Clouds [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Ld Guilford's Whim [also available in Gray's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Sr Francis Burdet's Victory [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Middlesex Election [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Capt Sowdens Fancy [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Madame Recaimers Waltz [also available in Gray's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Monsr Garnerins Flight [also available in Gray's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Rattling Morgan [also available in Gray's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Beggar Girl [also available in Thomson's 24 Country Dances for 1803] The Poney Race Picnicks Waltz [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Widow and no Widow [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] The Pilot that Weather'd the Storm [also available in Thomson's 24 Country Dances for 1803] Union new Waltz [also available in Fentum's 24 Country Dances for 1803] A Trip to Preston Guild [also available in Gray's 24 Country Dances for 1803] |

| The New Roscius Country Dance Fan for 1805, 1804 [advertised in December 1804]  |

Female Volunteers [another tune of this name was circulating at this date but I've not identified the source of the tune on this fan],

Lord Grantham's Whim [also available in Campbell's c.1804 19th Book], The Humours of Dublin [also available in Campbell's 24 Country Dances for 1787], The Young Roscius [several tunes of this name were circulating at this date but I've not identified the source of the tune on this fan], The Arch Duke Charles's Waltz [also available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1805], Mrs Wybrow's Waltz, The Humours of Cork [also available in Preston's 24 Country Dances for 1805], Round the World for Irish [better known as the Irish tune Round the World for Sport, available in numerous collections including Corri Dusek & Co's c.1800 A Collection of Strathspey Reels], Earl Moira's Nuptials [several tunes themed around Lord Moira were circulating at this date, notably Lord Moira's Welcome to Scotland, but I've not identified this tune], Female Jockey [A different tune named The Female Racer is in the Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1805], The Goe, Coll Bryl or One of the Temple Young Roscius was a child actor born in 1791, he was a minor celebrity in 1805. The fan includes a variety of tunes some of which were published for 1805, others are older or of uncertain provenance. This fan was advertised for sale in the Morning Post newspaper for the 13th December 1804. |

I've yet to find evidence of Country Dance fans being published after about 1806, interest in them may have waned. The convention by which the top couple (or top lady) would select the tune and figures to be danced hadn't changed but perhaps the willingness of the public to purchase these fans had. We're in the realms of conjecture at this point, but perhaps a sufficient number of ladies had called a dance from her fan, only to be embarrassed by the professional musicians not having heard of the tune before, that their willingness to purchase more such fans had faded.

My impression is that the 24 Country Dances for the Year X publications were falling from favour around the start of the 19th century; music publishers invested ever decreasing effort into their production, many such dances involved a combination of tune and figure that weren't even compatible! If fan producers copied those same tunes then their clients might be unimpressed with the results. The better quality Country Dance publications took the form of numbered sheets issued monthly by music shops rather than cheap annual collections, the "for the year" suffix was no longer especially relevant to dancers. Dancers, perhaps, were more interested in tunes and dances that were genuinely popular in London, rather than the tunes that publishers hoped would become popular in the following season. Newspapers increasingly named the tunes being danced by the aristocracy and travel across the nation was an ever improving experience, ladies who purchased the dance fans would be more aware as time went by that the fans did not in fact reflect the figures as danced as court, etc.

that they appeared to claim; this may have hastened the end of both the country dancing fan and the annual collections.

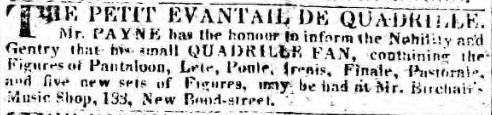

Figure 8. Advertisement for Edward Payne's fan, Morning Post, 24th February 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 8. Advertisement for Edward Payne's fan, Morning Post, 24th February 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Approximately a decade after the Country Dance fan seems to have fallen from interest a new phenomenon arose: a Fan that assisted the user to dance Quadrille dances. There may be a naive similarity between the Quadrille and Country Dance fans, in reality they're as different from each other as the dances themselves.

The Quadrille was a new dance form that gained popularity in London c.1816; it had evolved out of the Cotillion dances (which had been popular in the later 18th century), the Quadrilles were catapulted to significance in the wake of the Regent's Fete of July 1816. The challenge of the Quadrille is that it was a choreographed dance form, the dancers had to have memorised several sequences of figures prior to the performance. The later 1810s saw a plethora of Quadrille dances being issued, each with its own set of figures; social dancers struggled to keep up. A convention of Calling

or Prompting

of Quadrille dances would subsequently emerge as the 1810s progressed, that took a while to become conventional however. The Quadrille fans offered a more immediate solution - the figures of the quadrilles were printed on them such that dancers could refer to their fans while dancing at a ball.

The Quadrille fans were successful and at least one design saw multiple editions. The Country Dance fans of the 1790s were issued by fan manufacturers, the Quadrille fans of the 1810s were issued by dancing masters (or at least by authorities on Quadrille dancing). We can speculate that the Country Dance fans may have been used by a leading lady when selecting a dance; the Quadrille fans in contrast could be used by any dancer, it's possible that every dancer in the set would use a copy.

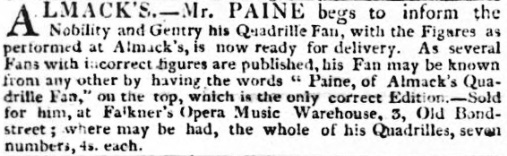

Figure 9. Advertisement for James Paine's fan, The Courier, 31st May 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 9. Advertisement for James Paine's fan, The Courier, 31st May 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Two different Quadrille fans were advertised in London from approximately the same date. The dancing master Edward Payne (1792-1819) advertised the first from early 1817 (Morning Post, 24th February 1817, see Figure 8): Mr Payne has the honour to inform the Nobility and Gentry that his small Quadrille Fan, containing the Figures of Pantaloon, L'ete, Poule, Trenis, Finale, Pastorale, and five new sets of Figures, may be had at Mr Birchall's Music Shop

. Edward Payne was probably the first authority in London to publish the first set of Quadrilles, he had been teaching them prior to the 1816 Carlton House ball that seems to have made them popular; he may even have rehearsed the performers for that event. An advert published for Dovey's Haberdashery (Morning Chronicle, 17th May 1817) indicated that they had the new Quadrille Fan

available for sale, they presumably saw a market for Payne's fan.

Payne's fan must have been somewhat successful as a few months later his rival James Paine (1779-1855) (leader of the orchestra at Almack's Assembly Rooms) published his own equivalent fan (The Courier, 31st May 1817, see Figure 9): Mr Paine begs leave to inform the Nobility and Gentry his Quadrille Fan, with the Figures as performed at Almack's, is now ready for delivery. As several Fans with incorrect figures are published, his Fan may be known from any other by having the words

. Paine's claim that Paine, of Almack's Quadrille Fan,

on the top, which is the only correct Edition.several Fans with incorrect figures

existed suggests that further quadrille fans may have been in circulation that are no longer known, Payne's may not have been the only such fan.

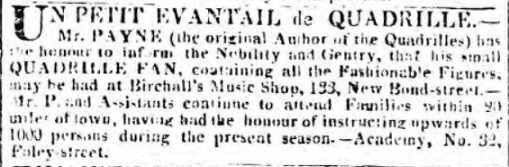

Edward Payne responded with a further advertisement for his fan (Morning Post, 4th June 1817, see Figure 10) in which he described himself as the original author of the Quadrilles

and added that Mr P. and Assistants continue to attend Families within 20 miles of town, having had the honour of instructing upwards of 1000 persons during the present season.

. The figures offered by Paine and Payne were very similar; Payne's tended to be more detailed (he was a dancing master after all), whereas Paine's tended to be a little vague (he was a musician rather than a dancer); but it was Paine's as danced at Almack's

arrangements that went on to be the more successful; subsequent editions of Payne's publications would evolve his figures to better match those of Paine. You can read more about how to dance the first set of Quadrilles in our paper on that subject. The irony, which we'll discover when studying Paine's fan below, is that the Quadrilles as danced at Almacks in 1817 seem not to have been consistent with the Paine's own publications - his as danced at Almack's

slogan may not have been as straight forwards as it seems.

Figure 10. Second advertisement for Edward Payne's fan, Morning Post, 4th June 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 10. Second advertisement for Edward Payne's fan, Morning Post, 4th June 1817. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The year 1818 saw increased interest in Quadrille Fans. An advertisement published in the Cheltenham Chronicle (3rd September 1818) promised that they could be purchased from Mrs Cooper's Harp and Piano-Forte Repository, they were presumably available elsewhere around the country too. James Paine had published his 10th set of Quadrilles in May 1818 (Morning Chronicle, 19th May 1818), he issued a new edition of his Quadrille Fan to accompany it. Paine continued to advertise his new Quadrilles and his Quadrille Fans into 1819 (eg Morning Post, 6th July 1819); the same year saw J. and D. Slowan, Book and Music Sellers, Newcastle advertise Paine's Quadrille Fan

as being available for purchase. The fans were increasingly available around the country. A further Fan containing 12 sets of Quadrilles was published in London in 1820, seemingly without reference to either Paine or Payne, though the contents were derived from Paine's publications.

The dancing master Thomas Wilson advertised his own Quadrille Fan from early 1822 (Morning Post, 14th January 1822) on a completely new design. The earlier fans had listed the figures of the Quadrilles as a memory aid; Wilson's fan included information on how to perform the figures of the Quadrilles. He explained that it contained: Diagrams of all the Quadrille and Cotillion Figures, with lines in each figure to follow (correctly drawn from life in practical performance), alphabetically explained in English, with the technical terms; the whole selected and arranged from the Quadrille and Cotillion Panorama, by T Wilson; calculated expressly to refresh the memory as well of the scientific performer as learner.

. Wilson may have been a little late to the market however, by 1822 the interest in new choreographies was beginning to wane; a handful of well know sets of Quadrille Figures were increasingly used as the 1820s progressed. Moreover, a convention of Calling

or Prompting

of Quadrille figures had arisen in the Assembly Rooms; dance historian Richard Powers has shared an excellent paper investigating the phenomenon. The era of new and varied figures was largely over by the mid 1820s, I know of no further Quadrille fans published thereafter.

We've investigated two different varieties of dance fan in this paper. The Country Dance fans seem to have been novelties, possibly intended to assist a leading lady to Call a successful country dance; the Quadrille fans aimed to help any dancer remember the choreographed routines of the most popular quadrille dances. The Country Dance fans proliferated in the 1790s and early 1800s, the Quadrille fans in the late 1810s; both were likely to be relatively affordable and were aimed at ordinary

dancers. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of copies of these fans will presumably have been produced, yet surviving examples are exceptionally rare today; in some cases only a single copy is known - presumably the owners of these fans used them and over time they wore out.

We've presented all of the examples of these fans that we know of; if you have access to further such fans, or have any other information to share, then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved