|

Paper 45

Programme for a Cotillon Ball, 1799

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 20th July 2020, Last Changed - 1st March 2025]

A cotillon (or cotillion) ball was held in the port city of Bristol in the year 1799. It wasn't an especially important ball, very little is known about it at all, but the programme of dances from the event does survive. This paper will investigate the concept of a Cotillon Ball and attempt to reconstruct the dancing from this specific event.

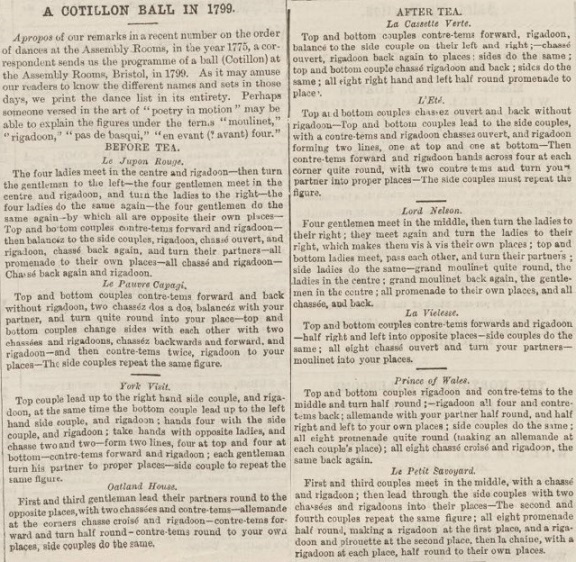

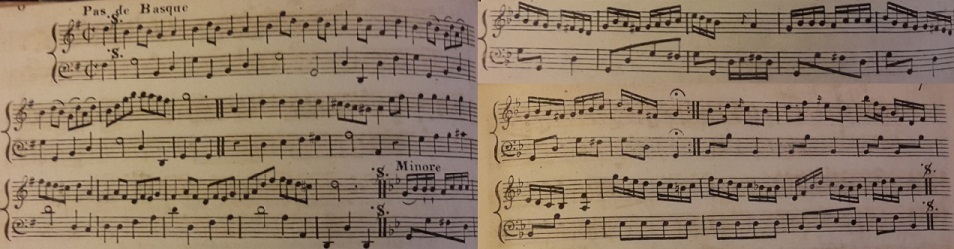

Figure 1. A Cotillon Ball in 1799 from the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for the 11th September 1890. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

An important characteristic of Cotillion dances is that they were choreographed, the dancers were required to know (and ideally have memorised) the figures that would be danced in advance. The figures for the dances used at our event were distributed to the attendees in preparation, probably as a printed sheet, a copy of those figures still survives... after a fashion. Ephemeral matter of this type tends not to be archived, it's used and then disposed of, it's only luck that allows us to investigate this specific event. The extant copy of the figures was printed in transcript form in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette newspaper nearly a century after the event in the year 1890! The programme was printed as a curiosity, the editors considered the event from nearly a century earlier to be a suitable historical amusement for their readership to enjoy; a reader evidently owned an original copy of whatever had been distributed back in 1799, it was offered up to be reprinted, it's that transcript that survives today (see Figure 1).

The dances we'll investigate in this paper are:

The terms Cotillon and Cotillion are, for the purposes of this paper, interchangeable. I prefer to use Cotillion unless quoting a source that does otherwise; other variant spellings for technical terminology will also be found within this paper.

The Cotillon Ball of 1799

The 1890 transcript was printed in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette newspaper for the 11th of September 1890. The port city of Bristol hosted the ball, Bristol is located around 40 miles from the spa town of Bath, it was heavily influenced by the social conventions established at Bath. Bath was, back in the 1790s, arguably the most influential location for social dancing in Britain - visitors to the Spa would arrive from across the nation, they would mingle with people they didn't already know and they would dance together at the town's Assembly Rooms. The Cotillion dance arrived in Britain from France and gained popularity in the mid to late 1760s, it became popular in Bath and subsequently spread across the nation. The success of the Cotillion dance in Britain reached its peak in the 1780s, it then experienced a slow decline towards the end of the 18th century, only to re-emerge in the early 19th century in the less fussy form of the Quadrille dance. Bristol may (perhaps) have retained the Cotillon Ball for longer than many other towns, it was a decidedly old-fashioned dance by the turn of the century, it's moderately surprising that a Cotillon Ball was being hosted in 1799 at all.

The transcript from 1890 (see Figure 1) begins as follows:

Apropos of our remarks in a recent number on the order of dances at the Assembly Rooms, in the year 1775, a correspondent sends us the programme of a ball (Cotillon) at the Assembly Rooms, Bristol, in 1799. As it may amuse our readers to know the different names and sets in those days, we print the dance list in its entirety. Perhaps someone versed in the art of poetry in motion may be able to explain the figures under the terms moulinet, rigadoon, pas de basqui, en avant (?avant) four.

This introduction was followed by a list of four named cotillion dances, with figures, that were described as being before tea and six more that were after tea . A small horizontal rule separates every two dances, this may simply have been for formatting purposes, but it could imply that the cotillions were grouped in pairs (perhaps implying that the same group of dancers would remain together for two complete cotillion dances). It's possible that the original source material included further text now lost: for example, the introduction references pas de basqui steps, a phrase that doesn't otherwise feature within the transcript as we have it. The text that we do have is undoubtedly genuine however; the possibility of minor transcription errors can't be denied, but the terminology and arrangement of the figures is too perfect for it not to be a legitimate late 18th century text. The 1890 editors may not have known what some of the technical terms meant but they faithfully reproduced them. One of the dances is named Lord Nelson, this title helps to date the collection to no earlier than 1798 (the date at which Admiral Nelson received his viscountcy in the wake of victory at the Battle of the Nile); the given date of 1799 for the ball therefore seems both reasonable and likely.

An immediate difference between the description of this Ball and those of other Balls we've studied will be obvious: on this occasion we know the dancing figures that were actually danced, rather than the names of the tunes alone. The previous balls we've studied in our preceding papers consisted mostly of Country Dances , they were unchoreographed dances in which the calling couple were invited to select figures immediately before the dance began; Cotillion dances, in contrast, required synchronised movement from all of the dancers. A Cotillion typically required eight dancers (arrangements for sixteen dancers were uncommon but not unknown) who would move in synchronised patterns; synchronisation required rehearsal, the publication of the figures would be an essential aide-memoire for the dancers, instructions might be kept about the person and used in-situ at the ball itself.

The 1890 introduction began by referencing a previous newspaper column that had in turn referenced events held in 1775; that earlier column was printed in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for the 21st August 1890, it reported the following:

It may interest some to know how their forefathers were wont to enjoy themselves in Bath. The following, under date April, 18, 1775 is recommended by Captain Wade, the M.C., as the programme of amusements for the remainder of the season:-

Monday - The Dress Ball at the New Rooms

Tuesday - Public Tea and Cards at the New Rooms

Wednesday - The Cotillon Ball at the Old Rooms

Thursday - The Cotillon Ball at the New Rooms and Public Tea and Cards at the old Rooms

Friday - Dress Ball at the Old Rooms

Saturday - Public Tea and Cards at the Old Rooms

Sunday - The Rooms to be open alternately for Tea and Walking.

There were evidently two weekly Cotillon Balls held at Bath in 1775; balls of this nature continued to be mentioned in the Bath press throughout the 1780s.

By the early 1780s the Cotillion dances enjoyed at Bath each season would be published in small annual collections. For example, the Bath Chronicle for 6th January 1780 advertised Printed very small and neat for the pocket, FIGURES of all the New and most Fashionable COTILLONS, As danced in the Public Rooms at Bath for one shilling. Two further such collections were advertised in 1781; the Bath Chronicle (12th July 1781) advertised FIGURES of 29 of the most favourite COTILLONS danced at the Public Assembly-Rooms in Bath, may be had of the Printer of this Paper, and of all the Booksellers in Bath, price One shilling ; then (27th December 1781) This Day is published, Price One Shilling, The Third Edition of A Second Collection of COTILLONS, being THIRTY of the most favourite Figures danced at the Public Assembly-Rooms, in Bath. Printed by and for R. Cruttwell, and sold by all the Booksellers in Bath, &c. Of whom may be had, The Third Edition of the FIRST COLLECTION of COTILLONS, being 29 favourite Figures danced in the Rooms at Bath . A third book of figures for use at Bath was published in 1782 (Bath Chronicle, 31st October 1782) and a Sixth book in 1789 (The Times, 11th September 1789). It's unclear how long this convention lasted; the idea of a seasonal collection of dances is one that persisted, most notably with the annual collections of dances issued by such authorities as Francis Werner and Thomas Budd (Budd's annual dance collections continued to be issued into the early 19th century).

By 1792 the interest in Cotillon Balls at Bath was in decline, the Bath Chronicle (6th December 1792) reported: The MASTERS of the CEREMONIES, finding the COTILLON BALLS not so well attended as in former years, and it having been suggested to them that an Alteration in the Entertainments of the Evening would be acceptable, submit the following Arrangements to the Subscribers to that Ball and the Public in general; ... the name of COTILLON BALL be changed to that of FANCY BALL, At which Ladies will be allowed to appear in Hats, or any Mode of Dress (that of Character excepted) which they may think most elegant and becoming. The Ball to commence with a Country Dance, after which there will be one Cotillon only and then Tea. After Tea, a Country Dance, One Cotillon, and the evening to conclude with Country-Dances, and the Long Minuet . Balls consisting entirely of Cotillons were to be phased out, thereafter the Country Dance would be the principal form of entertainment. The Cotillon Ball didn't disappear from Bath entirely in 1792 of course; for example, Mr Deneuville advertised his own First Subscription Cotillon Night in 1794 (Bath Chronicle, 30th October 1794); he promised that Ladies and Gentlemen will be regularly instructed in the Figures and Steps used in Cotillons, Quadrilles, &c. . A year later Mr Mercie advertised (Bath Chronicle, 14th May 1795) that Having lately been in Paris, he likewise teaches the newest Cotillon-Steps, Cotillons, &c. &c. . Occasional references to both the tuition in and dancing of Cotillions sporadically appeared around the country throughout the 1790s and into the early 19th century, only at a far lower frequency than had been known in the 1780s. It's entirely possible that Cotillion Balls continued to be enjoyed nationwide, but as newspaper references to them decline in the early 1790s it seems likely that our 1799 Ball was a late example, it was a form of entertainment that was rapidly disappearing. Individual Cotillion dances would continue to be enjoyed in Ballrooms from time to time in the early 19th Century, an 1807 reference to an entire Cotillion Ball at the Assembly Rooms in Margate exists (Morning Post, 8th October 1807), so too a Cotillion Ball at Bath (Daily Advertiser, 1st February 1808). A Cotillon Ball was also held in Bath in 1806 (Daily Advertiser, 22nd Jan 1806) at which Fourteen cotillions were danced in seven different sets , this sounds similar to our ball of 1799. The 1815 An Epitome of Brighton described a weekly Cotillion Ball as being held at the Castle Assembly Rooms in that city in 1815, they may of course have been dancing something more akin to the Quadrille dance by that date. On a related note, Clementi & Co published some collections of dances in 1810 and 1811 that they described as being Selected for the Cotillion Balls and yet their dances were what later writers would term Quadrilles (we've written more of the Clementi dances elsewhere). These later 19th century cotillion balls seem not to have been cotillions balls of the form that would have been recognised in the late 18th century.

The Cotillion Balls of the late 18th Century

So what was a Cotillion dance, and what was a Cotillion Ball? Such questions are deceptively difficult to answer; most of what we know about Cotillion dancing derives from instruction books published in London c.1770, such texts are incredibly useful but the conventions of the late 1790s may have evolved. In the absence of clear descriptions of how the late 1790s Cotillion was danced we may have to make a few assumptions. We've written about Cotillion dancing in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more about the dance in general; we've also investigated the Cotillions danced at Bath across the 1780s elsewhere; this paper will concentrate on what is most likely to have occurred at our ball. If you want to know about the form of the cotillion, the concept of changes , the steps that were used and the wider context of the dance, you might like to read our other papers to learn more.

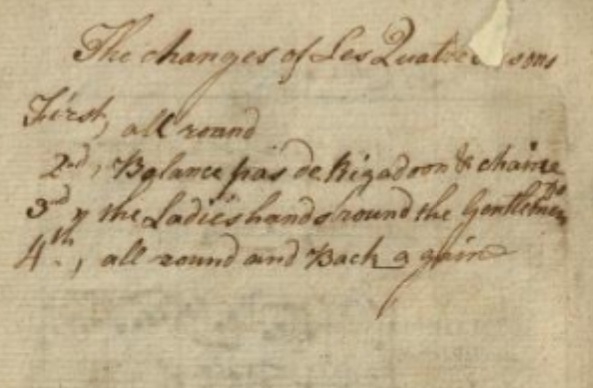

There are a great many things we can't know: how many sets of dancers were there, how long did each dance take to perform, which steps did they use, how well rehearsed were the dancers, were the figures announced as the dance was in progress, was there a walk through of the figures prior to the dance, etc.? We can make some educated guesses however. For example, we know that there were four cotillions to be danced before tea and six after, there's only so much dancing that can be squeezed into a single event - there must have been some concessions to timeliness. If, for example, only a single set of eight dancers were to perform at a time, then it's unlikely that many individuals would receive a chance to perform each dance. It seems more likely that as many sets as were inclined to dance would form-up concurrently and that all would dance at the same time; the figures for all of the dances had presumably been distributed to all of the attendees, more than one concurrent set remains probable for that reason too. When the cotillions were first introduced to Britain in the late 1760s it was common to dance a proscribed sequence of changes , this would result in perhaps a dozen iterations of each dance; that strict formality could be a burden however, it's unclear whether it persisted. Logic suggests that extended arrangements would be unpopular; the formality would tire the dancers and would significantly extend the time it would take to dance all ten cotillions from our ball. Whereas, one c.1770 dance collection that I've studied contained a handwritten set of four changes to be used (see Figure 4), perhaps the owner and their friends felt that three or four iterations were sufficient for them. Numerous cotillion collections included the list of changes to use, but as each list differed in the minutiae of detail, most assemblies must have had their own local conventions; whether they danced four iterations or ten is unknowable, it's likely that our dancers of 1799 would dance whatever was generally considered to be comfortable.

A fascinating poem was published in 1811 that described the cotillion dancing conventions at Bath (The Wonders of a Week at Bath, in Doggrel Address), it offers some insight into the preparation for cotillion dancing that may be relevant to our ball:

...

But enough of these matters; this night there'll be millions

To look at the elegant sets at cotillions;

And really this dance is no trifling concern,

For it takes a dull fellow a fortnight to learn;

They seldom are out, to be sure, for the fact is,

They go to the rooms in a morning to practise,

In a gay dishabille, or, just as it suits,

The girls in their clogs, and the men in their boots:

You'll see with some wonder how earnest they look

Now down at their legs, and now up at their book;

For know, my young Sir, that you'll never succeed in

The dancing cotillions, unless with hard reading;

Both spelling and hopping, 'twont do for a dunce

To try two such difficult matters at once;

...

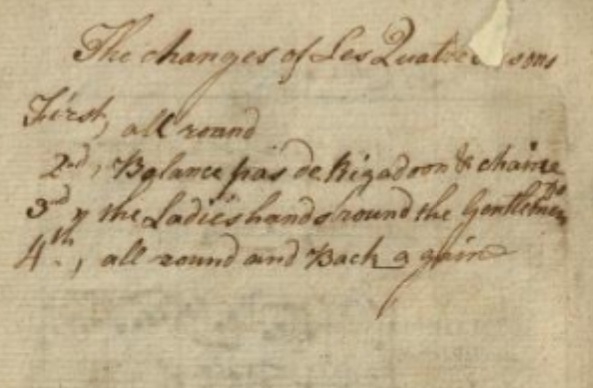

Figure 4. The Changes of Les Quatre Saisons. A hand written collection of four changes for a cotillion dance; the date of the annotation is unknown, it was found within a copy of Mr Siret's c.1770 A set of Cotillons or French Dances.

The implication is that study was required for dancing cotillions, that instructions were issued for the dancers to read, and that informal rehearsal opportunities were available in the mornings for any who needed them (perhaps as depicted in Figure 3). The poem goes on to describe the fictional, but presumably based on genuine experience, injuries that some dancers have sustained while dancing cotillions.

The requirement for rehearsal may have been an unwelcome chore for some. An advertisement from colonial Calcutta referred to the subscription assemblies there recently taking on the name of Cotillion Assemblies (Calcutta Gazette, 27th of October 1791). It continued: it is thought proper to give this public intimation, that Minuets and Country Dances will continue the principal Part of the Amusement, and that Cotillions will seldom or ever be danced, as few will be inclined to go through the Fatigue of Practice previous to the Performance . It's possible that a similar sentiment would have been held at Assemblies across Britain.

A commentator in the early 1780s (Morning Herald, 16th September 1782) complained of unrehearsed dancers at the Hampstead Assembly: He begs leave also to put the Hamstead beaux in mind to perfect themselves in their cotillons before they come into the Ball-room; as it is not only ridiculous, but impertinent in those who pretend to lead down a dance, to make the company wait till they have learnt the figure of it from a book, or have with much difficulty been made to comprehend it by their more accomplished partners! . It's no surprise that some individuals were less well rehearsed than might be hoped for, the problem was clearly endemic. George Keates in his 1779 Sketches from Nature made a similar comment: I must own I am rather sorry to observe, that the COTILLON begins to be introduced into our balls. How far more experience in those dances, may improve us in them, I know not; but I have scarcely yet seen the figure gone through without interruption. . It's likely that by 1799, the date of our ball, the only dancers still actively dancing Cotillions would be those who had danced them over many years and knew what they were doing, that certainly hadn't been the experience of prior decades.

Modern historical dance enthusiasts often expect Cotillion dances to have been Called or Prompted when danced in the 18th century. This is the convention whereby a Master of the Ceremonies (or similar) reminds dancers of the figure of the Cotillion as it is being danced. This seems not to have been the normal convention at the time however. Dance historian Richard Powers has shared an excellent paper demonstrating how the convention of Calling dances seems to have started with the Quadrille dance format in the 1810s. Dancers of the 1790s were expected to memorise the figures of their Cotillions.

Figure 3 shows a cotillion being rehearsed, it's an image dating to 1792. It appears to show a group of people meeting at a town's Assembly Rooms, with the music present, attempting to walk through a dance. There are sheets of paper being held by many of the attendees; it's likely that these sheets have the figures of the dances recorded on them, it may be a sheet of this nature that was the source of the text that was recorded in transcript form in 1890. One of the people depicted will be the dance director, it's unclear which; a group of dancers to the right of the image appear to be successfully dancing a cotillion, a couple towards the centre are attempting to dance an allemande turn, several others are scrutinising their instructions.

Our dancers of 1799 had probably been issued the figures for the cotillion dances in advance and had received the opportunity to rehearse those dances at the assembly rooms (with the orchestra present) prior to the date of the ball. They may have been dancing the same cotillions all season.

Observations on the Figures

The figures that are listed for the Cotillons are reasonable. They're consistent (the same figure seems to use the same amount of music wherever it appears) and they return the dancers back to where they started after each iteration. All seems to be as it should be. We don't have the original music that was associated with each dance, we don't even know how many bars of music should be assigned to each figure (though the use of hyphens as separators do offer a useful clue); there aren't any references to the changes so it's unclear what convention may have existed. Some reconstruction is required.

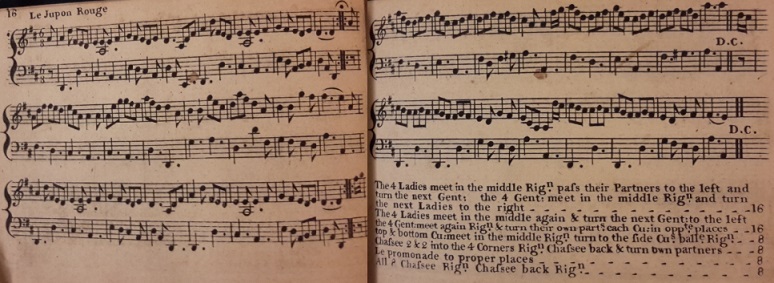

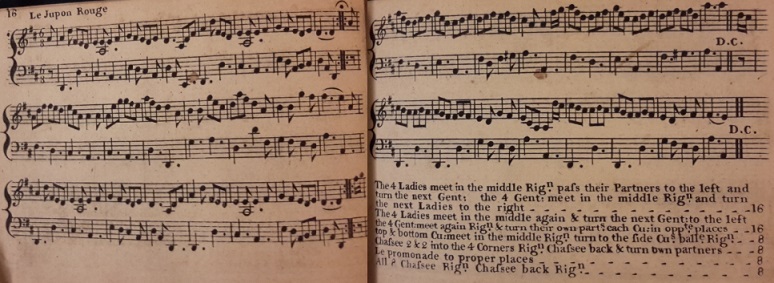

We do however have an incredibly useful cipher by which to interpret the dances; the first dance of the collection is named Le Jupon Rouge, it had previously been published in Thomas Budd's 1781 9th Book (see Figure 5). Budd published both the music and figures for the dance and he explicitly indicated how much music to assign to each figure; Budd's figures precisely match those from our ball (albeit using slightly different wording), it's clearly the same dance. It's curious that a dance first published in a collection for the year 1781 was still being danced in 1799, one might expect such things to be seasonal. The coincidence is useful for us, we can use Budd's exceptionally clear arrangement of the dance to remove most ambiguity from the surviving instructions for our ball; having done that, we can apply similar ideas to reconstruct the remaining dances. Once the timing of the figures has been reconstructed we can search for suitable tunes of a similar shape that might be employed in place of the unknown originals. An important observation is that Budd provided a strain of music in which the changes would be danced, it's therefore reasonable to guess that Changes were also danced at our ball (although the specific list of Changes remains unknowable).

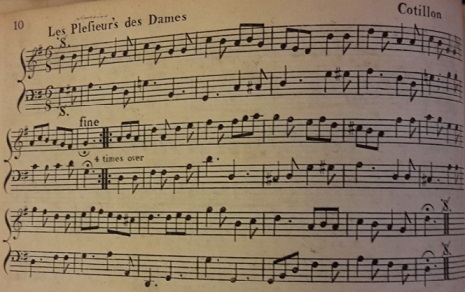

Figure 5. Thomas Budd's version of Le Jupon Rouge from his The Ninth Book for the Year 1781, Twelve Favorite Cotillons and Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.cc.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

It's possible that some of the other Cotillions from our ball had also been published elsewhere, at least one of the names is known from another collection. The most prolific Cotillion publishers of the 1780s were Thomas Budd and Francis Werner; sadly it is difficult to check their collections as so few of their volumes are known still to survive. If currently unarchived copies of their work should be uncovered then we may learn more. Given that one of the dances had previously been published by Budd, maybe several of them had been, it's certainly possible.

We'll now consider each of the dances in turn, estimate how much music is required to dance them, and suggest a possible tune that could be used in a modern recreation of the dance.

Le Jupon Rouge

This dance is especially interesting as it had previously been published in Thomas Budd's 1781 9th Book (see Figure 5), we therefore have both the original musical score and a second explanation of the figures. It was also published, with figures only (no musical score), in the 1784 edition of A Second Collection of Figures to Thirty of the most favourite Cotillons as now Danced at the Assembly Rooms, Bath. It was evidently a popular dance. Budd's tune consisted of four strains of music, the second of which is sixteen bars in length, the others being only eight bars in length. The final eight bars of the second strain were in fact a repeat of the A strain in this particular tune, it could therefore be expressed as a BA pattern. The resultant pattern of the music for the main figure (ignoring the changes ) involved 64 bars arranged in the pattern BA,BA,C,A,D,A. This Cotillion was the single most complex of the entire ball, we're lucky to have an independent arrangement of it.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

What follows is an arrangement of the dance with both the 1799 figures and Thomas Budd's equivalent 1781 figures taken into consideration:

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; Budd's music shows the A strain as being repeated; some of the classical cotillion changes only required 8 bars of music and others 16, the musicians were expected to modify the tune to match the requirements of the dancers. Cotillions traditionally started with a Grand Rond figure, though you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the sequence. |

| BA 1-16 |

The four ladies meet in the centre and rigadoon - then turn the gentlemen to the left - the four gentlemen meet in the centre and rigadoon and turn the ladies to the right . Thomas Budd offers slightly different text and explicitly indicates that these figures are to use 16 bars of music: The 4 Ladies meet in the middle Rign pass their Partners to the left and turn the next Gent; the 4 Gent meet in the middle Rign and turn the next Ladies to the right... 16 bars.

Budd's figures helpfully remove much of the uncertainty we may have had from reading the 1799 text alone. The first four bars involve the four ladies moving forwards (probably with a contretems movement) followed by a rigadon step sequence; the second four bars have the ladies turn the man from the couple that was to the left of their starting position (I'm inclined to suggest that's a two-handed turn towards the left) ending with the lady having moved one position to the left and the man remaining where he started. The following 8 bars repeat the sequence, but with the man moving forwards and then turning the lady on his right (perhaps with a two-handed turn towards the right). At the end of the figure everybody has a new partner and is 90 degrees removed from their starting position.

A contretems and a rigadon are very similar step sequences. The difference is that a contretems moves either forwards or backwards, whereas a rigadon remains on the spot; so two bars forwards with the fancy step, then two bars on the spot facing the person opposite repeating the fancy step. Then four bars to approach the nearest side and two hand turn back into the progressed square. As with most of the terminology, numerous spelling variants exist for these terms, you will encounter several variations within this document alone.

|

| BA 1-16 |

The four ladies do the same again - the four gentlemen do the same again - by which all are opposite their own places . Budd wrote The 4 Ladies meet in the middle again & turn the next Gent to the left, the 4 Gentlemen meet again Rign & turn their own parts each Cu in the oppte places ... 16 bars.

This sequence repeats the first 16 bars of the dance and causes everybody to progress a further 90 degrees around the set, everybody ends with their original partners in the positions opposite to where they started the dance.

|

| C 1-8 |

Top and bottom couples contre-tems forward and rigadoon - then balancez to the side couples, rigadoon . Budd wrote Top & bottom Cu meet in the middle Rign, turn to the side Cus, Balle Rign... 8 bars.

The 1799 text is quite unclear at this point, there's a run-on sentence that makes the phrasing of the dance difficult to understand; luckily Budd removes the ambiguity. The 1799 text specifically indicates to use a contretems and rigadon step when moving forwards (whereas the Budd text is slightly less clear in the step to use); the head couples meet in the middle with these fancy steps, turn 90 degrees to face the person to the side of them, then use the ballance and rigadon steps towards the person now in front of them. This sequence ends with everybody in two lines of four, the outside people are facing towards the middle and the middle people are facing towards the outsides.

|

| A 1-8 |

chasse ouvert, and rigadoon, chasse back again, and turn their partners . Budd wrote Chassee 2 & 2 into the 4 Corners Rign, Chassee back & turn own partners ... 8 bars.

This is the most awkward of the phrases of the dance as the timing is irregular. Everybody performs a chasse ouvert out to the side (typically by taking two hands with the person they're facing, then making two chasse steps away from the centre), and then rigadon ; they then chasse back to return, turn to face their original partners, then two hand turn back to the position opposite to where they started the dance. It's this final turn which is difficult, it might normally be expected to require four bars of music and yet it seems to only have two available; it could be more convenient to omit the chassee back instruction and to simply two hand turn partners in four bars. The figure will be especially difficult for the four centremost dancers as they have to turn 180 degrees away from the side couple in order to face their partner in order to perform a full turn in half the normal amount of music; omitting the chasse back will make the figure much easier for them. I'm inclined to think that there's a minor error in Budd's text that was reproduced into the 1799 text; either that, or that this is a clue that the music is intended to be played quite slowly.

This figure ends with everybody back in the square formation and opposite to where they started the dance.

|

| D 1-8 |

all promenade to their own places . Budd wrote Le promonade to proper places ... 8 bars.

This figure returns the dancers to their home positions. The couples adopt a promenade hold (several variants of which are available, it's quite likely that they would join their crossed arms behind their backs) and return back to their original places. It's likely that they would take four bars to progress 90 degrees around the square (reforming the square as they do so, perhaps acknowledging the couple opposite on arrival), then another four bars to progress the next 90 degrees. We're not told the direction around the square that the promenade should take, convention suggests a counter-clockwise progression.

|

| A 1-8 |

all chasse and rigadoon - Chasse back again and rigadoon . Budd wrote All 8 Chassee Rign, Chassee back Rign ... 8 bars.

This figure is more commonly referred to as a Chasse Croise ; everybody changes place with their partner using two chasse steps to move sideways (differing conventions exist to determine which partner goes in front of the other, ultimately it doesn't matter so long as everybody in the set does the same thing), they rigadon , then return and rigadon .

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

The dance then returns back to the start with the next Change being danced. Dancers may like to alternate which pair of couples move forward during the C phrase of the music, perhaps the head couples lead on the first iteration and the side couples on the second - the instructions don't say to do this, but it was a common convention, especially within the slightly later Quadrille dances.

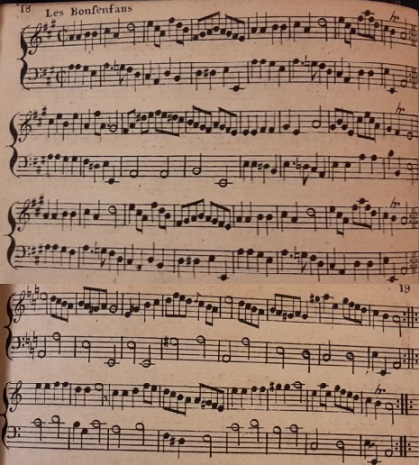

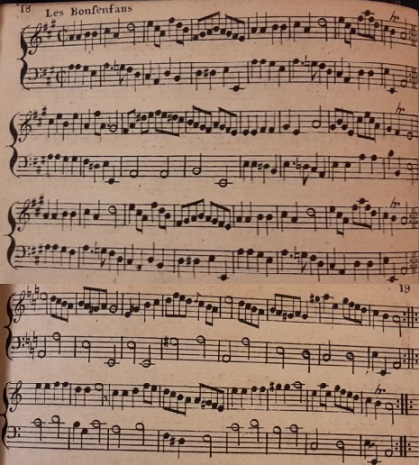

Figure 6. Thomas Budd's Les Bonsenfans from his The Ninth Book for the Year 1781, Twelve Favorite Cotillons and Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.cc.(1.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Neither the 1799 text nor Budd's 1781 text reference the dancing of Changes, this is despite Budd's arrangement quite clearly providing the music in which to do so; it's almost certain that Budd would have expected Changes to be danced. It's less certain that our 1799 dancers would have shared that same opinion, it's possible that they'd have used the initial A strain of music as an introduction and have begun dancing with the B strain - this convention would become an established part of the Quadrille dance a decade or so later, there may have been precedence for it as early as 1799. Several of the cotillions, as we will see shortly, are notably quadrillesque in their arrangement, it's plausible that the later style of dancing would be emerging at our 1799 date.

The 1799 text (as quoted in 1890) contains both hyphens and semicolons as separators, they offer some clue to synchronise the arrangement of figures to music; those clues are imperfect however, Budd was much clearer in his arrangement. The hyphens will prove useful when considering the other dances in the programme but we shouldn't rely on them providing a perfect demarcation of the musical arrangement; if they seem unreliable in the later dances then the evidence from Budd is that they could indeed be in error.

Le Pauvre Capagi

This Cotillion is less easily interpreted than Le Jupon Rouge as we we don't have an independent arrangement to compare it against; nor is the name of the tune known (at least to me) from other sources, so there are no external clues to be found. We'll reconstruct this dance from first principles.

An immediate observation is that the structure of the dance isn't entirely obvious. The figures, as written, involve the head couples enjoying all of the activity; the sequence then ends with the instruction The side couples repeat the same figure . This is an arrangement that may be familiar from Quadrille dancing, London's quadrille dances of the mid 1810s routinely featured activity for the head couples that would then be repeated for the side couples; this could be an argument for omitting the Changes from our Cotillion entirely and dancing it straight-through as though it were a Quadrille dance. The term Cotillion was less widely used at our 1799 date than it had been in the preceding three decades, the term French Country Dance sometimes replaced it; one of the implications of this terminological shift is that the stricter protocols of the old style of Cotillion dancing were going out of fashion, the less fussy Quadrille dance would emerge as the favoured style of dance in the 1810s. We could, therefore, interpret this Cotillion dance a-la-Quadrille . The counter argument to this idea is that Cotillions of the 1770s could feature this same repeating structure but with a Change inserted as and when required, arguments can be made in favour of either arrangement.

Three major arrangements would each make sense. We could arrange the dance as Change-heads-sides (repeat) which is the classic Cotillion arrangement with the main figure needing 64 bars of music; as Change-heads-Change-sides (repeat) which will take less time to dance as the Changes are exhausted faster and the main figure requires only 32 bars of music; or as Heads-Sides (no repeat) which is the typical Quadrille arrangement where the entire dance takes only 64 bars of music. These different structures have implications for the musical arrangement that will be required.

We'll arrange our reconstruction as a regular Cotillion of an earlier date, with Changes included, the main figure will require 64 bars of music. There are many ways the music in turn could be arranged, for our reconstruction we'll use a tune that is also sourced from Thomas Budd's 1781 9th Book named Les Bonsenfans (perhaps that should have read Les Bons Enfans , see Figure 6). We'll modify the repeating structure of the tune so as to result in a BB,C,D,BB,C,D arrangement for the main figure; this particular tune has a 16 bar B strain of music the second half of which is as actually a repeat of the A strain, it could therefore be expressed as a BA,C,D,BA,C,D arrangement.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music, as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

|

| B 1-8 |

Top and bottom couples contre-tems forward and back without rigadoon, two chassez dos a dos

The head couples take 2 bars to contretems forward, then two to return; the contretems is a fancy step sequence that results in the dancer taking two steps forwards, the head couples essentially meet in the middle and then back-out to places. A contretems would often be followed by a rigadon step, but on this occasion it is explicitly omitted. If this were a quadrille dance of the 1810s then the equivalent instruction would be En avant quatre en arriere , an instruction that means essentially the same thing.

The second half of the instruction is slightly less clear as two chassez may refer to two dancers chasseing, or to two chasse steps being taken forwards. It probably implies that the four head dancers approach the person opposite them, pass around each other back-to-back, then return back to places (taking four bars of music in which to do so). This is a common Quadrille dancing figure that might simply be written as Dos-a-dos in the 1810s. Indeed, this entire figure is notably quadrillesque. The figure ends with all eight dancers in their starting positions.

|

| A 1-8 |

balancez with your partner, and turn quite round into your place

The head couples turn 90 degrees to face their partners then perform a 4 bar balancez figure. A balancez is a fancy setting step that keeps the dancer in the same position; it might be a slow step to the right and back again, it might be a longer quadrille style Chasses a droite et a gauche , the main requirement is to take four bars and to return home with the music.

The head couples then turn their partners around in 4 bars of music. This is likely to require a two handed turn, though the instructions aren't clear. The equivalent quadrille instruction of the 1810s might be Balance a vos dames, et tour de deux mains , an expression that is clear about taking two hands with your partner. The figure ends with all eight dancers in their starting positions.

|

| C 1-8 |

top and bottom couples change sides with each other with two chasses and rigadoons, chassez backwards and forward and...

This is the most problematic figure in the dance as the instructions are a little unclear. The sentence structure from our 1890 text implies that there should be further activity squeezed within our eight bars of music, that seems unlikely when the figures themselves are taken into consideration. It's nonetheless possible that an irregular arrangement of the figures-to-music really was intended.

The expression change sides was sometimes used to imply changing places with your partner, but the context on this occasion strongly suggests that the head dancers pass each other and then turn to face each other. This is a relatively fast movement, there are two bars in which to use two chasse steps to pass the opposite dancer by the right shoulder, then two bars in which to turn in to face each other with a twisting rigadon step sequence; this should leave all eight dancers in two straight rows. The head dancers then retreat in two bars into opposite places to where they started, then advance in two bars back again. On this occasion the instruction is Chassez rather than Contretems but the quantity of movement will be the same.

This figure ends with all eight dancers in two straight lines.

|

| D 1-8 |

... rigadoon, and then contretems twice, rigadoon to your places

This figure sequence is the extension of the previous slightly confusing section; the 1890 text places a hyphen between the first rigadon and the rest of the text, thereby implying that the rigadon should be included within the C section of the music. That seems improbable; our arrangement has the rigadon at the start of the D phrase of music. The dancers perform a rigadon for 2 bars, then advance past their opposites (passing right shoulder) using two contretems step sequences (of 2 bars each) in order to get to their original start-of-dance positions, then 2 final bars of music are used in another twisting rigadon step sequence in order to turn back into the set.

This figure ends with all eight dancers in their starting positions.

|

| BACD 1-32 |

The side couples repeat the same figure.

The previous 32 bars of dancing are repeated for the side couples, this time it's the head couples who stand still and watch.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

Alternative arrangements of this dance are clearly possible and you might like to provide your own music to dance it to. We'll go on to discover that several further potentially quadrillesque cotillions were danced at our 1799 ball, you might like to consider arranging this dance as though it were a quadrille of the 1810s.

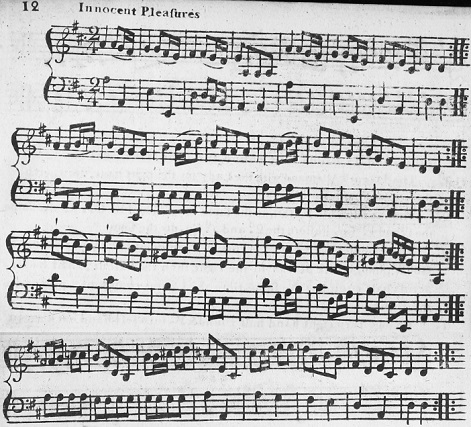

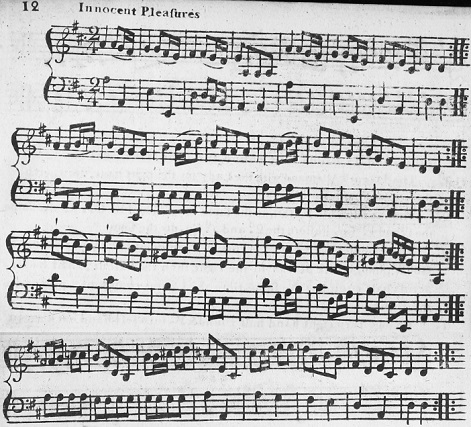

Figure 7. C Feuillade's Innocent Pleasures from Four new Minuets in 3 parts, Six Cotillions, Eighteen Country Dances & 2 Hornpipes for the Year 1782.

York Visit

The third cotillion at our ball was named York Visit, an immediate and unusual attribute of this dance may be evident: it is named in English. Almost all cotillion dances published in Britain were named in French; this doesn't necessarily imply that they were republished from a French original, just that the French origins of the dance form were emphasised in the dance titles. Whereas this dance, together with several others from our ball, is named in English. The name itself is likely to refer to the Duke of York (the second son of King George III); the cotillion after this one in the programme is named for what was then the Duke's official residence at Oatlands House, the possibility therefore exists that both cotillions were named in combination and in reference to a visit to Oatlands, perhaps even in reference to the 1799 Oatlands Fete that we wrote about in a preceding paper.

The dance, once again, features a sequence of figures for the head couples in the cotillion followed by the instruction side couple to repeat the same figure . This dance could therefore be interpreted as a primordial Quadrille dance of the type that emerged in the 1810s; a difference on this occasion compared to Le Pauvre Capagi is that the figure sequence includes simultaneous activity for all four couples. Most quadrilles of the 1810s provided figures for the head couples alone, then repeated it for the side couples, in strict sequence; our cotillion is less quadrillesque than Le Pauvre Capagi; it's most similar in form to a finale quadrille of the 1810s, a finale was the last dance in a set of Quadrilles, they typically involved simultaneous movement for all of the dancers (though not necessarily in each figure). Our Cotillion could be interpreted as a Quadrille or as a traditional Cotillion.

A further oddity of this dance is that the couples are referred to using absolute positional references. The phrases right hand side couple and left hand side couple are used in such a way as to reference an external observer, rather than being relative to the dancers themselves. The uncertainty from this terminology is the location of the observer; they could be located below the bottom couple and be looking up the room, or above the top couple and looking down the room. An argument could be made in favour of either option, the more probable answer is that the observer was at the top of the room facing down; this is traditionally where the band and master of the ceremonies would be situated, it's also the location of the presence in older styles of country dancing, the top most couple in a cotillion are implicitly the leading couple and figures might be arranged from their perspective. Several of the c.1770 cotillion guides hint at this same absolute naming convention. Modern dance instructions tend to use terminology that is relative to the dancers, not to an external observer.

We'll arrange this dance as a regular Cotillion with 48 bars of movement between each Change. For our reconstruction we'll use a tune named Innocent Pleasures sourced from C. Feuillade's Four new Minuets in 3 parts, Six Cotillions, Eighteen Country Dances & 2 Hornpipes for the Year 1782 (see Figure 7); this tune was also named in English. The tune is arranged in 2/4 time signature and shows the individual strains to be repeated, we'll alter that arrangement slightly by repeating the sequence. The repeating structure of our tune (ignoring the Changes) is B,C,D,B,C,D.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music, as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

|

| B 1-4 |

Top couple lead up to the right side couple, and rigadoon, at the same time the bottom couple lead up to the left hand side couple, and rigadoon

The head couples move so as to stand in front of the side couple on their right resulting in two lines of four dancers across the set; they are instructed to lead which implies taking inside hands with the man moving slightly ahead of the lady to lead her into position (he has slightly further to travel). The movement might be conducted with a contretems like step sequence curving towards the side dancers. Upon arrival the head couples perform a rigadon step sequence on the spot facing the side couple; the side couple might like to rigadon at the same time in acknowledgement.

|

| B 5-8 |

hands four with the side couple...

the 1890 instructions are a little unusual at this point, they call for a hands four figure and appear to require a rigadoon in the same strain of music. Combining both actions into the same strain would be awkward, it seems to make more sense for the rigadon to be delayed into the following strain of music. Whether or not the 1890 instructions faithfully reproduced the 1799 text is unknowable, it seems likely that the text is slightly in error.

The head couples join hands with the side couple that they're facing and circle once around.

|

| C 1-8 |

... and rigadoon; take hands with opposite ladies, and chasse two and two; form two lines, four at top and four at bottom

This figure sequence begins with the rigadon step sequence that we've delayed from the previous figure. It then includes a curiously named chasse two and two figure; observant readers may recognise that this is the same term that Thomas Budd used in his version of Le Jupon Rouge to describe a movement that our choreographer termed chasse ouvert . This results in a interesting question: did our choreographer intend a chasse ouvert to be used in this dance (using different but equivalent words in order to do so), or did they understand something different by the term?

A chasse ouvert might be expected to require 2 bars of music (4 bars in our 2/4 time signature music) but we seem to have 6 bars of music to fill, that in turn suggests a more interesting figure may have been intended. When we discussed chasse ouvert in Le Jupon Rouge we were faced with the inverse problem, that dance appeared to require too much movement from the dancers for the amount of music that was available. It's almost as though the instructions for the two dances have been transposed; the long figure from Le Jupon Rouge is needed in this dance and the short figure from this dance is needed in Le Jupon Rouge. That is how we've arranged the two dances for this reconstruction.

Following the rigadon sequence all eight dancers take two hands with the person they're facing and chasse ouvert outwards with two chasse steps; then return with two chasse steps inwards; then drop hands as the two lines of four turn to face each other, everybody moves two steps backwards into two lines of four at the top and bottom of the set.

|

| D 1-8 |

contre-tems forward and rigadoon; each gentleman turn his partner to proper places

Everybody takes a contretems step sequence forwards then performs a rigadon step sequence towards their parter. The four original couples then take two hands with their partner and two hand turn back to their original positions.

|

| BCD 1-24 |

side couple to repeat the same figure.

The previous 24 bars of dancing are repeated with the side couples taking the lead, the lines of four produced at various points in the dance will be up and down the set rather than across the set.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

Alternative arrangements of this dance are possible and you might like to discover your own tune to dance it to.

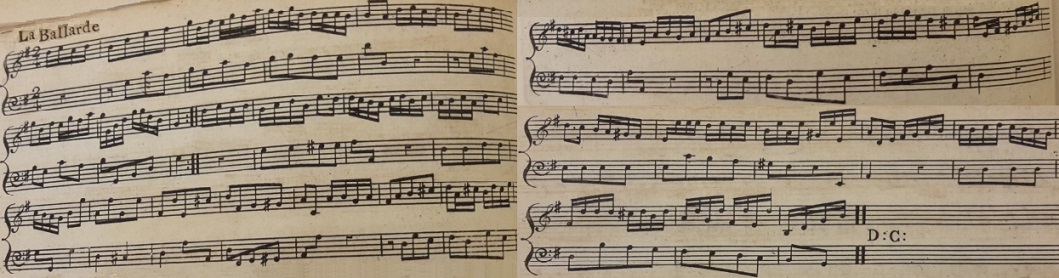

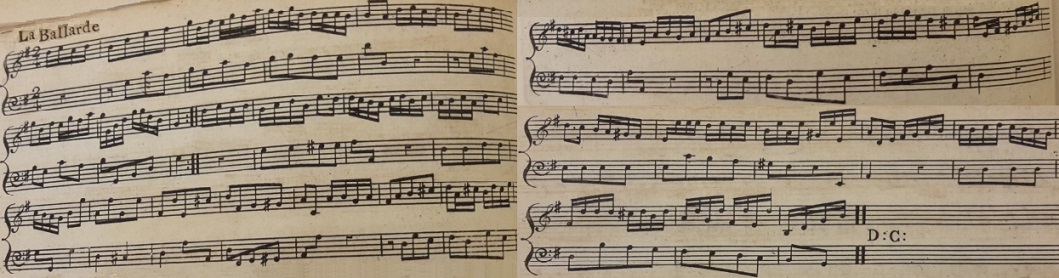

Figure 8. Martin Platts Junior's La Ballarde from Book XXII for the Year 1788, Eight Cotillions & Six Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.52.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Oatland House

This dance was the fourth of the event and the last of the before tea section of the ball. The dance itself is named in reference to Oatlands House near London, the home of the Duke and Duchess of York (the Duke was the second son of King George III). As we speculated above, this dance together with York Visit may have been named as a pair, perhaps in reference to a visit to Oatlands House, potentially even in reference to the 1799 Oatlands Fete that we've studied in a previous paper.

This particular cotillion is a bit of a challenge to reconstruct as the instructions, as preserved, are mildly perplexing. It's likely that the dancers at the event itself would have received tuition in the dances in advance of the ball; the printed text would have been a memory aid, they weren't expected to learn the figures for the first time from that text and would not be misled by any ambiguities within the text. They, unlike the modern interpreter, would not be confused by any unclear or even cryptic instructions within the text.

The primary area of confusion involves the initial lead their partners figure; the term lead usually implies a promenade or queue du chat figure in which the head couples change places in a curving movement; but we're explicitly instructed to use two chassees and contre-tems in order to change places, an instruction that usually implies movement in straight lines. If changing places in a straight line it might be more convenient for the dancers to arrive in opposite positions improper (the man in the lady's position, and the lady in the man's position); whereas the more typical figure would have the dancers arrive in proper positions. The remainder of the dance might be interpreted quite differently depending on how this initial figure is interpreted. It's notable that one of the other cotillions of the evening named L'Ete included a hands across figure that was to be danced with two contretems which implies that our choreographer was comfortable with using a contretems step sequence to proceed around a curved track.

As with several of the preceding cotillions, this one ends with the instruction side couples do the same . This cotillion could therefore be interpreted as a form of quadrille dance in the style of the 1810s, or as a regular cotillion in either 24 or 48 bars of music. We will arrange it as a regular Cotillion in 48 bars of music. The tune we've selected to match it to is named La Ballarde and can be found in Martin Platts Junr's Book 22 for 1788. This tune consists of two strains of music, an 8 bar A strain for the Changes and a 24 bar B strain (see Figure 8); if the figures were arranged to a four part tune then they would involve a repeating structure of B,C,D,B,C,D but for our tune they're simply BBB,BBB. This particular tune begins and ends with a half bar of music, this identifies the tune as being arranged in the gavotte rhythm ; dancers might decide to dance with their steps synchronised on the half bar in the gavotte style.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

|

| B 1-4 |

First and third gentlemen lead their partners round to the opposite places, with two chassees and contre-tems

The head couples have four bars in which to swap places, arriving proper at the other side. The typical approach would be for the two couples to take promenade hold and to cross as couples on the right side of the set (passing each other by the left shoulders) and then curving around into positions; but we're informed to use two chassees and contre-tems to cross. This instruction could be interpreted various ways; it could be two passes of a chaine anglaise , except that this would not involve leading ; it could involve a pousette style movement into the centre of the set and a contretems into places; it could involve a chasse croise ; it could involve the man moving slightly ahead of the lady such that the four dancers almost form a ring moving to the left ending with a contretems step sequence into places.

On balance of probability I suspect that the four dancers should come close to forming a ring; two chasse steps are used to form the ring and to push it half way around to the left, then hands are dropped so that the four dancers can use a contretems step sequence to move into opposite places.

The figure ends with the head couples having swapped places, but remaining proper with the man to the left of the lady.

|

| B 5-8 |

allemande at the corners...

All eight dancers turn to face the person they're adjacent to and use four bars of music to allemande turn in four bars of music. An allemande is a fancy movement in which the dancers interleave their arms in order to turn around each other; various different allemande variants existed, the most common involved the two dancers turning right shoulder to right shoulder, linking right elbows, and joining hands behind their backs (left hand behind their own back, right hand behind their partner's back). They would then circle clockwise around each other using their linked elbows as a pivot, it's a relatively intimate turn.

The figure ends with everybody in the same position they were at when the figure started.

|

| B 9-16 |

...chasse croise and rigadoon

The head couples (or all four couples if you prefer) chasse croise in two bars, this involves a sideways movement in order to change places with your partner; then two bars to perform a rigadon step sequence into the set; then two bars to dechassez back again, and two bars to perform a second rigadon step sequence. Different conventions existed for the chasse croise , some dancers might prefer the lady to pass in front of the man, others might prefer her to pass in front for the first pass pass and for the man to pass in front for the return; it doesn't matter so long as everybody knows the convention that will be used.

The figure ends with everybody in the same position they were at when the figure started.

|

| B 17-20 |

contre-tems forward and turn half round

The head couples use a contretems step sequence to move forwards in two bars of music, then they swap places with the person they're facing in two bars. I suspect this turn would involve taking two hands with the opposite person and turning half around in a clockwise direction. The phrase turn half round is a little confusing; one might suspect it to be a hands four figure rather than a couple figure, but the same instruction in the subsequent Prince of Wales cotillion is quite clearly a couple figure so it's likely to mean the same thing in this dance.

The figure ends with two rows of four dancers across the middle of the set; the side couples remain facing in as they have been for most of the dance, the heads have progressed past their opposites but remain in the centre of the set facing away from the person they have just turned.

|

| B 21-24 |

contre-tems round to your own places

The head couples return home to their original places with two contretems step sequences; the first (in two bars) will take them to their partner's original position, they then turn to face their partners and use one more contretems (in two bars) to pass their partner's right shoulder into their own home positions.

The figure ends with everyone back where they were at the start of the dance.

|

| B 1-24 |

side couples do the same.

The previous 24 bars of dancing are repeated with the side couples taking the lead.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

It is after this dance that the programme scheduled a tea break.

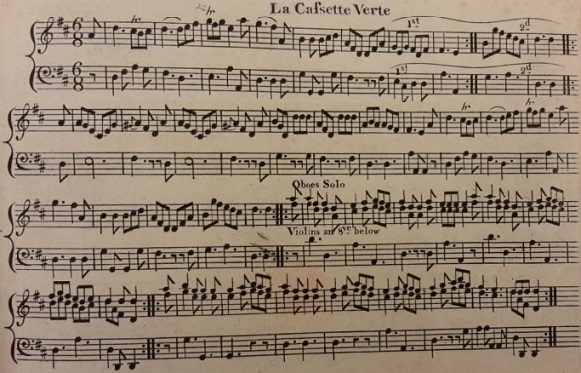

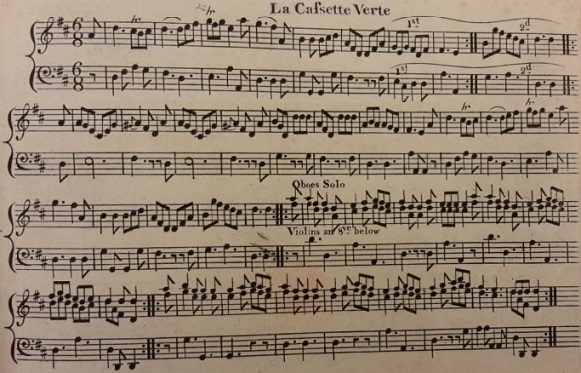

Figure 9. La Cassette Verte from an unnamed c.1785 collection engraved by Thomas Skillern. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, d.64.j ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

It's unclear to me as to whether typical cotillion dancers of the late 18th century would dance with a comprehension of gavotte rhythm or not; the Norwich based dancing master T.B. Bruckfield referenced gavot steps as being appropriate for use in cotillions in his 1787 Eight Cotillons, Eight Country Dances, & Two Favourite Minuets, he described the step as follows:

is very natural, and is the ground-work of the Cotillons; and, is done in making the rounds, courses, and figures, each of them is equal to half a Bar; and, altho' every Step ought to be regulated in its motion, and of an equal distance; yet there are cases in which it is necessary to lengthen or shorten them accordingly, besides which, it is to be observed, that the Minuet Step is sometimes used.

As interesting as this reference may be, it does not indicate that gavotte steps are arranged to the music in an unusual way. Dancers might like to recreate this this dance to a gavotte rhythm.

La Cassette Verte

This cotillion was the first that was scheduled to be danced after tea .

We're lucky that a cotillion tune with the same name as our dance does in fact survive in an undated and untitled c.1785 publication engraved by Thomas Skillern, we can therefore use the Skillern music with our dance (see Figure 9). The copy of the Skillern publication that I've studied has lost its cover, the title is therefore unknown though the contents clearly claim to be engraved by Skillern; the British Library have given this work the invented title of A Collection of 10 minuets for 2 violins and bass, printed in score, and 3 suites of country dances. The Skillern music is perfectly compatible with our dancing figures (though the figures printed by Skillern himself are entirely different); it seems probable that the Skillern tune is what would have been danced at our 1799 event, the compatibility of the arrangement seems too perfect to have been achieved by chance.

The title La Cassette Verte refers to the ministerial green boxes used by the French government, a minor novel of the same name had been published by Monsieur de Sartine in 1779.

The tune engraved by Skillern (as with the example by Budd above) explicitly allocated an A strain of music for use in dancing the Changes for the cotillion, it's therefore reasonable to assume that it would have been danced with Changes at our event of 1799. Skillern's music is in four distinct strains, the second of which is 16 bars long, the others being only 8 bars in length. A single iteration of the figures would take the pattern BB,BB,C,C,D,D for a total of 64 bars of music.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

Our music introduces a minor variation in the last two bars of the A strain when repeated; if an 8 bar change is to be danced then only play the second part of the A strain.

|

| B 1-8 |

Top and bottom couples contre-tems forward, rigadoon, balance to the side couple on their left and right

The head couples use a contretems step sequence to travel forwards meeting in the middle in two bars, then use a further two bars to perform a rigadon step sequence on the spot. The following four bars are a little more confusing; the most likely interpretation is that the four head dancers turn to face the person to their side and balance for four bars. A balance is a setting step, it's typically quite slow and involves a step to the side and a return. The side couples may balance in return if they wish, the instructions do not require them to do so. The later quadrille dances often arranged a balancez as a longer step sequence to the side and back again; a quadrille style of chassez a droite et a gauche could be danced here.

The figure ends with all eight dancers in two lines across the centre of the set; the side couples remain where they started, the head couples have moved forwards and turned to face the nearest side couple.

|

| B 9-16 |

chasse ouvert, rigadoon back again to places

The dancers join two hands with the person facing them and chasse outwards for two bars and perform a rigadon step sequence for two bars; they then chasse back into the middle for two bars, and the head couples retire back to places in two bars.

The figure ends with everyone back where they were at the start of the dance.

|

| B 1-16 |

sides do the same

The previous 16 bars worth of figures are repeated with the side couples leading; this time the line of four dancers will stretch vertically across the set rather than horizontally.

The figure ends with everyone back where they were at the start of the dance.

|

| C 1-8 |

top and bottom couple chasse rigadoon and back

The head couple chasse croise in two bars, perform a rigadon step sequence in 2 bars, chasse back in 2 bars, and rigadon for a further two bars.

The figure ends with everyone back where they were at the start of the dance.

|

| C 1-8 |

sides do the same

The previous figure is repeated for the side couples.

The figure ends with everyone back where they were at the start of the dance.

|

| D 1-8 |

all right hand and left half round

Everybody turns to face their partner and half turns them with the right hand in order to change places in 2 bars of music, they then swap places with the next person they meet using the left hand in another two bars, and repeat two further times. This figure is often referred to as a Chain .

The figure ends with everybody having progressed four places and ending opposite to their original starting positions.

|

| D 1-8 |

promenade to place

Everybody takes a promenade hold with their partner and progresses one place anti-clockwise around the set in four bars of music, then repeat to progress a further place in the remaining four bars of music.

The figure ends with everybody back in their original starting positions.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

A curiosity of this dance is that the 1799 figures from our ball differ to those published by Thomas Skillern. It's clearly possible that a popular cotillion dancing tune might be arranged with more than one set of figures; that convention had always been true of country dances (it's not uncommon to find a dozen sets of figures arranged for the same country dancing tune), the same cannot be said for Cotillion dances however - this example is an unusual exception to the convention.

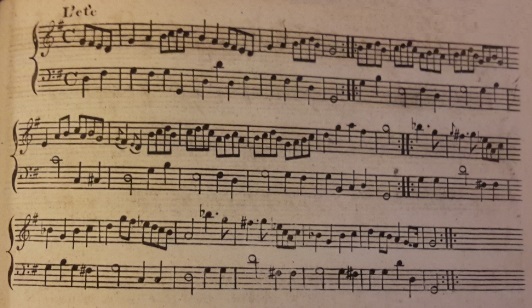

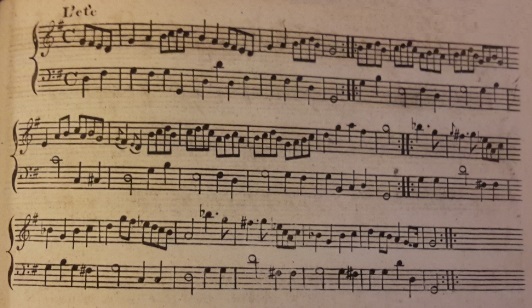

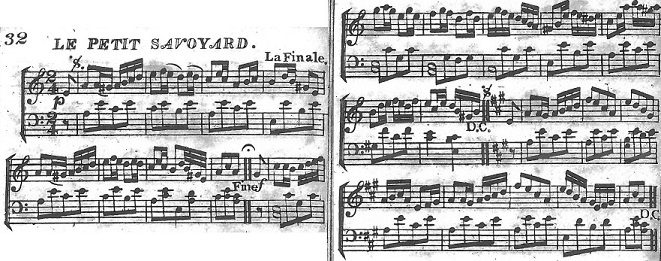

Figure 10. L'Ete from Francis Werner's Book XVII for the Year 1784. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.b.(5.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

L'Ete

This cotillion has a name that might be familiar; a popular sequence of Quadrille dancing figures of the 1810s were known under the same name of L'Ete, they're danced as the second Quadrille in many of the Quadrille sets of the 1810s and beyond. We've described how to dance the L'Ete quadrille figures elsewhere. Our cotillion does not use the figures that would become associated with Quadrille dancing, though several other cotillions had been published that did do so.

A cotillion dance named L'Ete was relatively well known in the 1780s; it was published by both Francis Werner in his Book XVII for the Year 1784 (see Figure 10) and also by Longman & Broderip in their 1786 Book the VI, Twenty Four New Cotillions. These two publications issued the same tune (with minor differences, notably the repeat markers) with similar figures attached. The Werner figures were somewhat similar to the later quadrille dancing figures, the Longman & Broderip arrangement was much more so - one might speculate that the later Quadrille figures were derived from the Longman & Broderip cotillion figures. Our L'Ete cotillion may be entirely unrelated to this family of French Country Dances, but as the name is shared it seems likely that the same tune was intended to be used. Our arrangement therefore uses the tune published by Francis Werner but adapted to the figures from 1799. This tune is a little unusual in that the A strain is only four bars in length.

Our cotillion figures end with the instruction The side couples must repeat the figure , this might offer a reason to arrange the dance as a quadrille of the style popular in the 1810s; we will arrange it as a Cotillion of the style danced in the 1770s. The main figure is 24 bars in length, which when repeated requires a 48 bar tune; using the music we've selected this results in a B,C,AA,B,C,AA structure. This does not match the repeat structure as printed by Werner, but it's closer to the structure printed by Longman & Broderip two years later. Once again the tune is arranged in the gavotte style with a leading half bar of music, dancers may be inclined to dance it to the gavotte rhythm.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

AA 1-4

(repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

Our music has a 4 bar A strain; I suggest that 8 bar Changes are danced throughout rather than 16 bar changes so that the A strain is played twice rather than four times through.

|

| B 1-8 |

Top and bottom couples chassez ouvert and back without rigadoon, Top and bottom couples lead to the side couples, with a contre-tems and rigadoon

The head couples chasse away from each other into the corner in 2 bars of music, and then return in 2 bars; the head couples then lead to the side couple on their right using a contretems step sequence in 2 bars of music, they then perform a rigadon step sequence in 2 bars. The second half of this figure is as described in the York Visit cotillion above.

At the end of the figure the eight dancers are stood in two lines of four across the set.

|

| C 1-8 |

Chassez ouvert, and rigadoon forming two lines, one at top and one at bottom; Then contre-tems forward and rigadoon

All eight take two hands with the person they're facing and then chasse outwards for 2 bars of music, they then perform a twisting rigadon step sequence in order to face their original partners in 2 bars. They will now be in two lines of four at the top and bottom of the set. All eight then advance forwards using a contretems step sequence in 2 bars of music and finally rigadon for two bars.

At the end of the figure the eight dancers are stood in two lines of four across the middle of the set.

|

| A 1-4 |

hands across four at each corner quite round, with two contre tems

All eight dancers turn to face the person to their side forming two groups of four in the process; each dancer joins right hands with the person diagonally across from them in the group of four and then circle once around. The dancers are told to use two contretems step sequences in order to perform that circle; this is an unusual instruction but it should be achievable.

At the end of the figure the eight dancers are stood in two lines of four across the middle of the set just as they had started the figure.

|

| A 1-4 |

and turn your partner into proper places

All eight dancers take two hands with their original partner and turn clockwise back to their original places.

At the end of the figure everybody will be in the positions from which they started the dance.

|

| BCAA 1-24 |

The side couples must repeat the figure.

The previous 24 bars of dancing are repeated with the side couples taking the lead.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

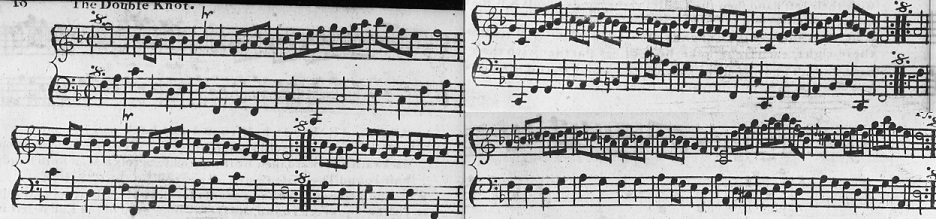

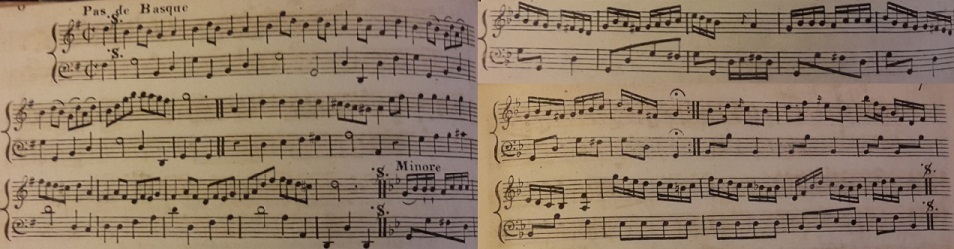

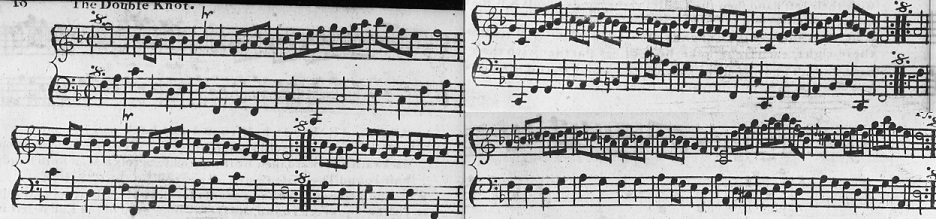

Figure 11. Pas de Basque from Francis Werner's Book XVI for the Year 1783. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.b.(4.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Lord Nelson

This cotillion was newly named at the 1799 date of our event; the honouree, Horatio Nelson, had only received the title Lord Nelson in 1798. The cotillion could have been known by another name at an earlier date but the given title dates to no earlier than 1798.

It's not entirely obvious how the figures for this cotillion were intended to synchronise to the music, our arrangement maps the main figures into 40 bars but alternative arrangements are possible. The music we've selected to accompany the dance is named Pas de Basque (see Figure 11), it was published in Francis Werner's Book XVI for the Year 1783. This tune has four strains of music, each of which is 8 bars in length; the music for the main figure will be arranged with a B,A,CC,D structure. This particular tune includes a passage in a minor key , this was a fairly common characteristic of Cotillion dancing music. An error in Werner's score may be noticed: the C and D strains switch from 4/4 time signature to 2/4 but without making that change clear. It's uncertain whether Werner intended the tempo of the tune to change at that point.

The convention for ending a cotillion could vary across different venues; most of the historical texts fail to address this issue, we're therefore uncertain of which conventions prevailed. Of those texts that do refer to ending the dance most hint that a cotillion would terminate with the last repetition of the main figure, not with a final Change . Nonetheless, some sources do suggest that a cotillion could be terminated with a Change , particularly with a Grand Rond (or Great Ring ). Our arrangement of this dance lends itself to termination with a final 8 bar change such as a ring, the music would end awkwardly without that final A strain. The main figure, in our arrangement, ends in a minor key; the music only returns to the major key with the next Change in the sequence.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

|

| B 1-8 |

Four gentlemen meet in the middle, then turn the ladies to their right; they meet again and turn the ladies to their right, which makes them vis a vis their own places

The four men move forwards and towards the lady to their right briefly acknowledging each other in passing, they two-hand turn that lady and end in her partner's original position in 4 bars of music; the four men then repeat the figure in a further 4 bars.

The figure ends with the ladies remaining where they started, and the four men having progressed into opposite positions from where they started.

|

| A 1-8 |

top and bottom ladies meet, pass each other, and turn their partners; side ladies do the same

The head ladies cross the set briefly acknowledging each other in passing, then two hand turn their partners to end opposite to their starting position in 4 bars of music; the side ladies then do the same in a further four bars of music.

The figure ends with all eight dancers opposite their original positions from the start of the dance.

|

| C 1-8 |

grand moulinet quite round, the ladies in the centre

The four ladies join right hands in the centre of the set, the four men hold their partner's left hand with their own left hand; in this grand moulinet position (approximately the form of a plus symbol + ) everyone rotates once around, the ladies drop hands in the centre and their partners turn them back into the positions from which they started the figure.

The figure ends with all eight dancers opposite their original positions.

|

| C 1-8 |

grand moulinet back again, the gentlemen in the centre

The four men join left hands in the centre of the set, the four ladies hold their partner's right hand with their own right hand; everyone rotates once around, the men drop hands in the centre and their partners turn them back into the positions from which they started the figure.

The figure ends with all eight dancers opposite their original positions.

|

| D 1-8 |

all promenade to their own places, and all chassee, and back

Each couple takes promenade hold with their partners and promenade back to their original positions in 4 bars of music, then each dancer chasse croise s with their partner and back again in 4 bars of music.

The figure ends with all eight dancers back in their original positions.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |

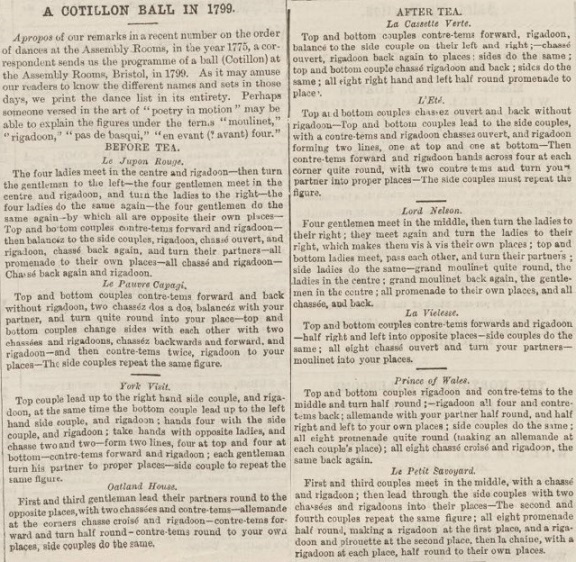

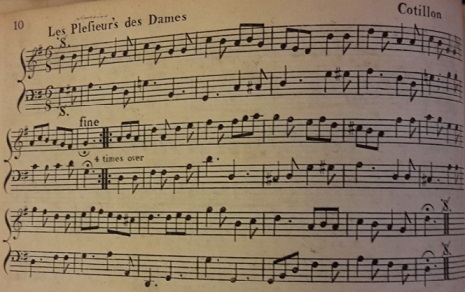

Figure 12. Les Plesieur's des Dames from Francis Werner's Book XIII for the Year 1780. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.c.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

La Vielesse

This cotillion appears to require an unusual number of bars of music, our arrangement uses an 8 bar strain followed by a 12 bar strain for the main figure. Most cotillions (as with most country dances) used music arranged in 8 bar strains, but not all did so. There are examples of published cotillions with 12 bar phrases, 20 bar phrases, and other irregular arrangements. The same was true of a minority of early Quadrille dances too, early arrangements of the La Pastoralle quadrille (for example) required 36 bars of music rather than the more normal 32 bars. Cotillion dances were choreographed such that the dancers had to learn the figures in advance of their performance; the music they were danced to would be similarly pre-determined. A tune with an uncommon structure could be paired with compatible figures to make for a slightly different dance; it's therefore taken a little more effort than usual to find a suitable tune for dancing this cotillion given the exotic structure of the dance. The term fancy dance was sometimes used to describe dances that were carefully arranged to suit the music and that couldn't easily be decoupled; this cotillion may therefore have been considered to be a fancy dance .

The tune we've selected is named Les Plesieur's des Dames (see Figure 12) and is taken from Francis Werner's Book XIII for the Year 1780. It consists of an 8 bar A strain which is notated to be repeated 4 times over followed by a 12 bar B strain. The main figure of the dance will use the music in an A,A,B arrangement. If we include two A strains for a Change then that does indeed involve repeating the A strain four times over. It may be noticed that the repeat markers around the B strain are mismatched, the leading marker implies repetition and the trailing marker doesn't; I find this to be a common occurrence in printed dance music of this date and not something to be concerned about - it could be arranged either way. Our arrangement does not repeat the B strain. The printed music then has a coda which would cause the A strain to be played again, in our arrangement we return to the start of the tune for the next Change in the sequence.

Rearranging a tune to suit the needs of a dance is an acceptable thing to do. As modern enthusiasts we sometimes think of a printed score as being sacrosanct and that it must be played as printed; dancers two hundred years ago did not share this expectation - a score was implicitly modifiable. We've explored this concept in some detail in a previous paper.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

| Musical Strain | Figures |

A 1-8

(optionally repeated) | The Changes; these may be danced in either 8 or 16 bars of music as required. Cotillions usually start with a Grand Rond figure, you can dance whatever sequence of changes you like. Each time the dance repeats it restarts with the next Change in the previously determined sequence.

|

| A 1-8 |

Top and bottom couples contre-tems forwards and rigadoon; half right and left into opposite places

The head couples advance forwards in 2 bars of music with a contretems step sequence, then perform a rigadon step sequence for 2 bars. They then give right hands to the person in front of them them and swap places moving into that person's original position in 2 bars, then give left hands to their partner to change places in 2 bars.

The figure ends with the head couples having swapped places.

|

| A 1-8 |

side couples do the same

The previous 8 bars of dancing are repeated for the side couple.

The figure ends with all four couples opposite to the position they were in when the dance started.

|

| B 1-4 |

all eight chasse ouvert...

All eight dancers move side ways away from their partner into the nearest corner in 2 bars of music, then return back again in 2 bars of music.

|

| B 5-8 |

... and turn your partners

All eight join two hands with their partners and turn clockwise once around in 4 bars of music.

|

| B 9-12 |

moulinet into your places.

The four ladies join right hands in the centre, the four men take their partner's left hand with their own left hand and in this grand moulinet formation rotate half way around before dropping back into their original places in 4 bars of music. The man should guide his partner into place following a curved track such that they arrive facing into the set. It's a relatively fast figure, approximately 2 bars of music are used to push the moulinet half way around, and 2 bars to sweep around into places.

|

| Return to the start for the next Change in the sequence |