| Return to Index |

|

Paper 36 Programme for a Second Royal Ball, 1813Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 26th June 2019, Last Changed - 5th September 2023]We've previously shared a paper investigating the dancing at a Royal Ball held at Carlton House in early February 1813. This paper continues the theme by investigating a second Royal Ball that was held at Carlton House, this time on Wednesday 30th June 1813. We'll compare and contrast the dancing at these two events, held just four months apart, you may like to read the earlier paper before proceeding with this one. The tunes we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

Figure 1. The first of the Royal Party to enter the Ball Room was Queen Charlotte, conducted by her son and host, George The Prince Regent, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

Figure 1. The first of the Royal Party to enter the Ball Room was Queen Charlotte, conducted by her son and host, George The Prince Regent, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

The Prince Regent's Ball &c. (Wednesday 30th June, 1813)This Ball was held at the Prince's personal palace at Carlton House in London, several newspapers described the Ball over the days following the event. We're once again lucky that the names of the tunes that were danced have been recorded for posterity. The following narrative is constructed from details printed in The Courier for 2nd July 1813 and also in The Morning Chronicle for the same day; both newspapers printed a significantly similar text, any dance references have been emphasised. The Prince Regent's Entertainment on Wednesday night, though not upon so extensive a scale as the Fete given soon after his accession to the Regency, was yet of the most splendid description. There were between 900 and 1000 persons present, and the dresses were of the most magnificent and costly sort. As it was the wish of the Prince to entertain his guests with as much ease and comfort as possible, the plan was adopted of laying supper in tents for a considerable number, as a cool retreat from the heat of the ball room and state-apartments; and this object would have been completely answered, provided the weather had proved favourable. A covered walk or grove had been provided, branching out right and left, on the entrance from the house to the temporary promenade, occupying the space of the house. It consisted of orange-trees, large branches of ivy, and curious trees, a variety of flowers and exotics, which were brought from Kensington, Hampton Court, and Kew Gardens for the occasion. They were illuminated by a great number of variegated lamps, and four Grecian lamps in the centre on each side. From the quantity of rain, however, that fell during the day, the company were obliged to forego the pleasure of walking in it, the rain having penetrated in several places, although every possible exertion had been made to make it weather-proof. The same was nearly the case with respect to the tents, as but few of the company, in comparison to the number laid for, would venture to sup in them, being fearful of the damp.  Figure 2. The next to enter were the Princesses Elizabeth and Mary, conducted by the Duke of Cambridge, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

Figure 2. The next to enter were the Princesses Elizabeth and Mary, conducted by the Duke of Cambridge, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

At eight o'clock, a party of the 7th Hussars marched into Pall-Mall, and men were stationed in different places to regulate the line of carriages. About the same time a party of Guards, under the command of Col. Clithero, with the Duke of York's band, marched into the Court-yard. The Duke of Cumberland's also attended, and played alternately. Soon after the Prince, conducting the Queen, entered the ball room, followed by the Princesses Elizabeth and Mary, conducted by the Duke of Cambridge; the Princess Charlotte by the Duke of York; the Duchess of York and Princess Sophia of Gloucester by the Duke of Kent. They were attended by the Prince's Officers of State. The Queen took her seat at the upper end of the room in a superb arm chair, attended by her Chamberlain, the Lady in Waiting, &c. The Prince of Orange followed soon after.  Figure 3. Next to arrive was Princess Charlotte conducted by the Duke of York, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

Figure 3. Next to arrive was Princess Charlotte conducted by the Duke of York, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

The second dance called for was Voulez vous danser Mademoiselle? which was led off by the same distinguished characters. Although the Princess Elizabeth did not join in the dance, she appeared to enjoy the amusement extremely, and her usual vivacity of disposition was very conspicuous. The next dance was Mrs McCleod, which Lord Aboyne had the honour of leading off with the Princess Mary, followed by the Princess Charlotte and the Duke of Devonshire. Till this dance was led off the dancers were not very numerous, owing to the crowded state of the rooms, numbers having retired to promenade the State Rooms. In the Octagon Room there was an abundance of the most choice refreshments.  Figure 4. The last of the Royal party were the Duchess of York and Princess Sophia of Gloucester, conducted by the Duke of Kent, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

Figure 4. The last of the Royal party were the Duchess of York and Princess Sophia of Gloucester, conducted by the Duke of Kent, Images courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust

After supper the dancing was resumed, when the following dances were led off by the Princess Mary and the Duke of Devonshire: Miss Johnson, Knole Park, and Lady Montgomery. The whole concluded with The Tank, led off by the Princess Charlotte and the Duke of Devonshire.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 2nd July 1813 featured essentially the same text as both the Morning Chronicle and The Courier, but with the additional detail of the dresses worn by over 50 of the senior lady guests. The descriptions include: The Ball had the misfortune to be held on a cold and wet night in June, the weather (as is so often the case) interfered with the carefully laid plans; but the approximately one thousand guests made the most of the event regardless. The palace was over-crowded due to guests refusing to promenade outdoors, this in turn restricted how many couples could dance; we know of eight dancing tunes that were named in the text, we'll consider them in turn.

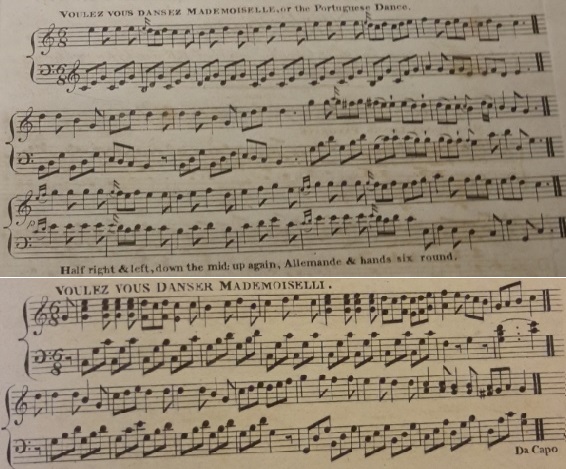

Figure 5. Voulez Vous Dansez Mademoiselle, or the Portuguese Dance, from Button & Whitaker's 1812 18th Number (top), and Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselli from Davie's c.1812 28th Number (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, P.M.84.(9.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 5. Voulez Vous Dansez Mademoiselle, or the Portuguese Dance, from Button & Whitaker's 1812 18th Number (top), and Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselli from Davie's c.1812 28th Number (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, P.M.84.(9.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon TownA numerous band appeared in a recess, and struck up the Royal Family's favourite dance - Gang nae mair to yon town, which was led off by the Princess Mary and the Marquis Cornwallis This dancing tune was the Prince Regent's personal favourite, it was to feature at many of the Balls that he is known to have attended at around this date, often as the opening tune of the evening. On this occasion we're informed that it was not only his favourite, but also that of the entire Royal Family. We've investigated this tune in some detail in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link for further details on this most eminent of Regency era dancing tunes. For futher references to the tune, see also: I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon Town at The Traditional Tune Archive

Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselle?The second dance called for was Voulez vous danser Mademoiselle? which was led off by the same distinguished characters

Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselle? was a tremendously popular tune, it was widely published in London between about 1811 and 1812, and was widely danced at society balls between about 1812 and 1814; the title can feature either the word I can't offer a precise chronology of publication. Some of the earlier music sellers to offer copies include William Dale in his c.1811 18th Number and W. Hodsoll in his c.1811 15th Number, both under the extended title of Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselle, or The Portuguese Dance; whereas Charles Wheatstone and his long term harmonist Augustus Voigt included it in their 1811 6th Book under the shorter title of Voulez Vous Dancer Mademoiselle. Other publications include Goulding's c.1811 23rd Number, Campbell's c.1811 26th Book, Davie's c.1812 28th Number (see Figure 5), Walker's c.1812 30th Number, James Platts c.1812 31st Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 16th Number and Button & Whitaker's 1812 18th Number (see Figure 5). It would subsequently be published in Glasgow in Cunningham's 1814 30th Number. It was also included in both Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room and Thomas Wilson's 1816 A Companion to the Ball Room. Nathaniel Gow included an arrangement of the tune in his Select Collection of Original Dances that was published in Edinburgh in 1815. Some of these publications included suggested dancing figures, where they did each suggestion was different.

Society references to the tune emerge around 1813, one of the more interesting involved yet another Royal Ball (Morning Post, 3rd June 1813) at which As with so many popular tunes, it only enjoyed a brief burst of significance. It would have been widely danced between about 1812 and 1814, less so thereafter. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1811 version, of James Platts's 1812 version and of Button & Whitaker's c.1812 version (see Figure 5). For futher references to the tune, see also: Voulez Vous Danser at The Traditional Tune Archive  Figure 6. Mrs McLeod of Eyre, from William Dale's c.1812 19th Number (top), and the 1809 Mrs McLeod of Rasay's Reel, from A fifth Collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c. (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

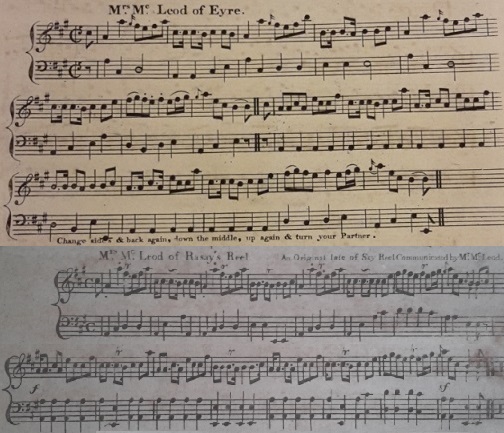

Figure 6. Mrs McLeod of Eyre, from William Dale's c.1812 19th Number (top), and the 1809 Mrs McLeod of Rasay's Reel, from A fifth Collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c. (bottom). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Mrs McLeod of Rasay's ReelThe next dance was Mrs McCleod, which Lord Aboyne had the honour of leading off with the Princess Mary

Dozens of tunes have existed over the years, published both in Edinburgh and London, with names that might perhaps be identified as our Mrs McCleod. Some were named for Miss or perhaps Lady McLeod, some for a McLeod

Our tune appears to have been first published by Nathaniel Gow in Edinburgh in his 1809 A fifth Collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c. under the title Mrs McLeod of Rasay with the added detail that it was an

The first reference I know of to the tune being danced socially involves the Perthshire Hunt Ball for 1810; the Perthshire Courier (8th October 1810) reported of the Ball that

It would take a couple of years more for the tune to become popular in London. It was reported of Lady Caroline Barham's Ball (Morning Post, 22nd June 1812) that For futher references to the tune, see also: Mrs. MacLeod of Raasay (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

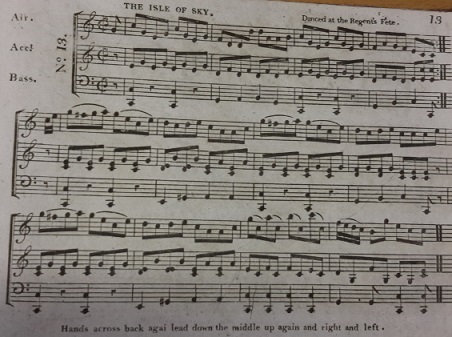

The Isle of SkyThe fourth dance was the Isle of Sky, which was led off by the same distinguished characters  Figure 7. The Isle of Sky, from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1813 Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c., Book 8th; Image courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), EFDSS.

Figure 7. The Isle of Sky, from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1813 Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c., Book 8th; Image courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), EFDSS.

This is a veteran tune of the Scottish dance tradition, widely published in Edinburgh throughout the second half of the 18th Century. It enjoyed a significant burst in interest in London in 1813 and 1814, but it had been known to Londoners from around the start of the 19th Century, perhaps much earlier. Several different tunes do share this same name but there's little room for ambiguity, most of the London publications use the name Isle of Sky to refer to the same tune over some seven or more decades. The tune is thought to be Irish in origin. The earliest publication I can confirm is from Scotland in Robert Bremner's c.1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (this collection is understood to have been issued from Edinburgh in parts over perhaps four years, then aggregated and reprinted in London c.1762). Subsequent publications in Scotland include John Anderson's c.1789 A Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys, Country Dances, English & French Dances, James Aird's c.1794 A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs, Vol IV, Robert Petrie's 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. and Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances.

One of the earlier London publications of the tune can be found in Goulding's c.1803 4th Number; I'm not sure of the publication date of this work, but I suspect that it was probably issued prior to 1805 (Goulding's 8th and 9th numbers seem to reference the 1805 Battle of Trafalgar, anything prior to the 8th number was probably issued prior to October 1805). It can also be found in Robert Mackintosh's c.1803 A Fourth Book of new Strathspey Reels, and also in Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore; it therefore seems probable that the tune was moderately well known in London during the first decade of the 19th Century. The clear evidence of interest arrives in 1813 when at least six publishers issued copies at around the same date; it's impossible to offer a precise chronology, but publications include: Skillern & Challoner's c.1813 19th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's 1813 8th Book (see Figure 7) and Button & Whitaker's 1813 24th Number. It can also be found in Wheatstone's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1814, and in both the Davie and Andrews collections. The Wheatstone & Voigt publication is especially interesting as they add the comment

There are several references to the tune being enjoyed socially; it was featured at two balls hosted by the Marchioness of Abercorn in 1801 (Morning Post 18th March 1801, and The Courier 24th March 1801), at The Duchess of Chandos's Ball in 1802 (Morning Post, 26th April 1802), at Lady Saltoun's Ball in 1803 (Morning Post, 24th March 1803), and at Her Majesty's Ball (Lancaster Gazette, 28th May 1803). It was also danced at the Derby Races Ball for 1813 (Derby Mercury, 16th August 1813) at which For futher references to the tune, see also: Isle of Skye (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Miss Johnston of Huttonhall's ReelAfter supper the dancing was resumed, when the following dances were led off by the Princess Mary and the Duke of Devonshire: Miss Johnson ... This is another tune that we've studied before, clearly a favourite of the Royal Family at around this date. You might like to follow the link in order to learn more.  Figure 8. Knowle Park, from Clementi's c.1809 6th Number; Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.232.a.(19.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

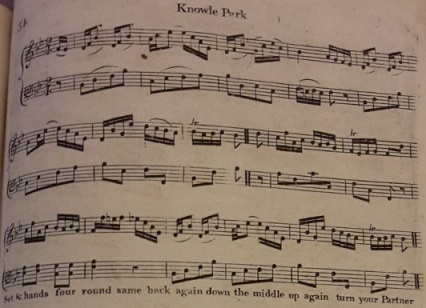

Figure 8. Knowle Park, from Clementi's c.1809 6th Number; Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.232.a.(19.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

For futher references to the tune, see also: Miss Johnston (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Knole Park... Knole Park ...

Knole Park in Kent was the home of the Dukes of Dorset; the Duchess was (according to the Morning Post newspaper) one of the guests at our Ball so it's likely that the tune was introduced in tribute to her. It's possible that she was invited to lead off the dance herself. Arabella Sackville, Dowager Duchess of Dorset (1767-1825) was the widow of the 3rd Duke (1745-1799) and the mother of the nineteen year old 4th Duke (1793-1815). The tune was, according to the Morning Post newspaper (4th of January 1808),

References to our tune emerge around 1807, it was widely published in London between about 1808 and 1810, but seemingly not thereafter. Our 1813 Ball is the only society event that I can confirm the tune was danced at. Another tune of the same name did circulate in the late 1780s in collections issued by Henry Bishop and Mr Smart, our tune seems unrelated to that older tune. Several of the early publications give the name of our tune as Miss Boyn, or Knole Park, it's unclear who London publications of the tune include Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 4th Number (under the name Miss Boyn or Knole Park) and Kelly's New Country Dances for the year 1808 (under the name Miss Boyn); James Platts's c.1808 6th Number, William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book, Button & Whitaker's c.1808 10th Number, Clementi's c.1809 6th Number (see Figure 8), Monzani's c.1809 9th Number, Ball's 1st Number and an unnumbered c.1808 collection issued by Halliday. It was also referenced in Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore. We've animated arrangements of William Campbell's c.1808 version and of Button & Whitaker's c.1808 version. Once again we have found a tune that experienced a brief burst of popularity, it probably remained fashionable for several years. The 1808 popularity of the tune is clearly evident from studying the London tune collections despite the tune remaining largely unknown from other sources, it was even danced at a Ball held by the Countess of Camden in 1808 (Morning Post, 4th January 1808). I know of no further societal references to the tune other than at our Royal Ball of 1813 however. This has potential implications for the more general identification of popular tunes; it's likely that many other tunes that were widely published were similarly popular but that luck has caused many of them not to be referenced in the newspapers. This tune was sufficiently successful that the Royal Family chose to dance to it, perhaps the same may have been true of other frequently published tunes. For futher references to the tune, see also: Knole Park at The Traditional Tune Archive  Figure 9. Lady Montgomries Reel, from Dale's c.1805 6th Number (top), and from Wheatstone's c.1804 2nd Number (bottom); Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

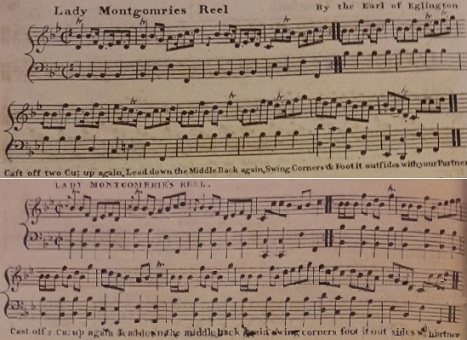

Figure 9. Lady Montgomries Reel, from Dale's c.1805 6th Number (top), and from Wheatstone's c.1804 2nd Number (bottom); Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Lady Montgomery's Reel... and Lady Montgomery.

This tune was tremendously popular in London between about 1805 and 1815, it was published many times and is known to have featured at numerous balls. One of the earlier editions was that of Joseph Dale c.1805 (see Figure 9), Dale credited composition of the tune to the Earl of Eglinton. Hugh Montgomerie (1739-1819), 12th Earl of Eglinton was a Scottish peer with a seat in the House of Lords. He was also a composer, numerous tunes have been credited to him, including an entire c.1796 collection of anonymously published New Strathspey Reels; it appears that he named this tune in honour of his wife Eleonora Montgomerie, Countess of Eglinton. The 1859 Memorials of the Montgomeries record's of Hugh that As far as I can determine this particular tune was first published in London, it was subsequently published in Edinburgh by Nathaniel Gow in his 1817 Part Fourth of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances. It's possible that the tune had found favour amongst the nobility in London before it came to be published by the major music sellers (if so, that's a characteristic we have previously noted when we investigated John Parry's 1810 The Persian Dance). There may be a Scottish publication I've yet to encounter that pre-dates the London publishers but it seems clear that the tune became popular in London before it was widely known in Edinburgh. The very first publication that I can identify was in London, it was issued by Charles Wheatstone in his c.1804 2nd Number (see Figure 9).  Figure 10. Mrs Lawrell's Ball, from The Morning Post, 21st January 1808. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

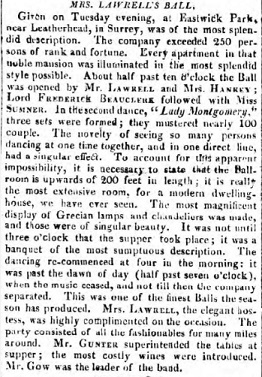

Figure 10. Mrs Lawrell's Ball, from The Morning Post, 21st January 1808. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

It's not possible to offer a precise chronology of publication, examples include: Dale's c.1805 6th Number (see Figure 9), Thompson's 24 Country Dances for 1805, William Campbell's c.1805 20th Book, Skillern & Challoner's c.1806 2nd Number, William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys, Walker's 1807 14th Number, John Paine's 24 Country Dances for 1807, James Platts's c.1808 5th Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1808 10th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1809 new edition of their 1st Book, and elsewhere. It was also listed in both Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and also in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. The subsequent Gow publication of the tune in Edinburgh attached a notice that the tune should be played

The society references to the tune are many. They begin with The Countess of Perth's Ball in 1804 (Morning Post, 24th March 1804) where

So far we've seen the tune danced by around 15 couples, 20 couples, 60 couples across two sets, and 6 couples; the next reference to the tune is really quite extraordinary, it featured at Mrs Lawrell's Ball (Morning Post, 21st January 1808, see Figure 10) at which for

The tune was also featured at the Duke of York's Birthday celebrations in 1810 (Morning Post, 18th August 1810) at which large marquees were erected on the lawn and the Gow band played; It's clear that this tune was a great favourite in the fashionable world. We've animated arrangements of Dale's c.1805 version (see Figure 9) and Skillern & Challoner's c.1806 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Montgomery's Reel (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

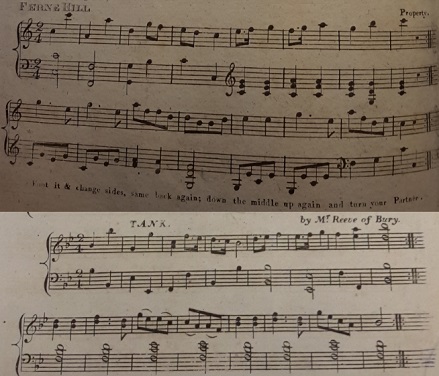

The Tank / Ferne HillThe whole concluded with The Tank, led off by the Princess Charlotte and the Duke of Devonshire. The Tank is an example of a tune that is largely forgotten today, but it has an interesting story and was popular for a few years around the start of the 1810s. The origin of the tune is subject to some debate however, several rival narratives are available.  Figure 11. Ferne Hill from James Platts's c.1809 13th Number (above), and The Tank from George Walker's 1811 26th Number (below). Images © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.t.(2.) and h.925.f. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 11. Ferne Hill from James Platts's c.1809 13th Number (above), and The Tank from George Walker's 1811 26th Number (below). Images © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.t.(2.) and h.925.f. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The first publication of the tune was probably that of James Platts in his c.1809 13th Number under the name Ferne Hill (see Figure 11). Platts didn't identify a composer of the tune but he did note that it was

The Lady Ashbrook in question was Deborah Susannah Flower, Viscountess Ashbrook (c.1780-1810) of Beaumont Lodge in Berkshire, first wife of Henry Jeffrey Flower, 4th Viscount Ashbrook (1776-1847). She died in 1810, shortly after transferring the tune to Platts but before it went on to become popular. The 1847 The Patrician wrote of Lord Ashbrook that Another of the early London publishers was George Walker, he included our tune in his 1811 26th Number under the new name of The Tank, he explicitly credited composition of the tune to Mr Reeve of Bury (see Figure 11). John Reeve of Bury St Edmunds was a moderately successful composer of tunes, he is credited with several from the Gray collection for 1812. Another publisher of the tune can be found in Button & Whitaker in their 1812 18th Number, their 1815 writ of response to James Platts credited Walker as the immediate source for their version of the tune. Charles Wheatstone published the tune both in his 25th Number and in his 1811 6th Book. Wheatstone's legal writ in response to Platts offered a more complicated origin story for the tune; he alleged that it had been composed overseas and had found it's way to Ipswich c.1810, that Mr Harrington of Bury had arranged it as a rondo at around that date, and that Mr Gray of Bury had printed it. Gray himself had allegedly offered the publishing plates for sale to Wheatstone, but Wheatstone refused the opportunity to buy them as the tune was already widely printed and considered to be common property.

The truth of the matter may never be fully known but the 1809 Platts publication does seem to have been the first to have been issued. Perhaps the tune had been played overseas and had found its way back to East Anglia under a new name, thereby confusing the provenance of the tune. The significance of the name Numerous London music shops issued the tune c.1811, we've named a few already. Others include William Dale's c.1811 18th Number, Campbell's c.1811 26th Book, Clementi's c.1811 arrangement in his 23rd Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 16th Number, Nathaniel Gow's edition of 1812 (issued in Edinburgh), and also the similar publications by Halliday, Goulding, Falkner and others. William Powers included it in his A Collection of Fashionable Dances for the Year 1812 that was issued in Dublin. It was also listed amongst the fashionable tunes within Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. Societal references to the tune are infrequent but do extend over several years. In addition to our 1813 Ball it was also danced at a Ball at Stratton in 1814 (Royal Cornwall Gazette, 9th July 1814) and also at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton in 1817 (The Courier, 18th January 1817). It's a fun tune, we've animated an arrangement of James Platts's c.1809 version (see Figure 11), Clementi's c.1811 version, Button & Whitaker's c.1812 version and of Wheatstone & Voigt's 1811 version.

ConclusionEight separate Country Dancing tunes were used for dancing at this Ball, many of them were of Scottish derivation though three were probably English; two of the tunes were in common with the February 1813 Ball that we studied in a previous paper, repeating favoured tunes from one Ball to the next was clearly considered to be acceptable. We've once again found that the tunes featured at a Royal Ball were widely published by the London music sellers, though some tunes were better known than others. Some of the tunes had been in circulation for decades, others were only of recent composition; two of the tunes were probably composed by the nobility, others were named in dedication to the nobility. The arrangement of the tunes can differ significantly from one publication to the next, as too would the suggested dancing figures. If you enjoy recreating historical Balls then the tunes we've investigated here would be highly suitable to use at your own events. An important observation we can draw from this historical Ball is that the weather can interfere with even the best laid of plans; this Royal Ball of 1813 was troubled with heavy rainfall that significantly affected the planned entertainments, but such is life. If you experience rain at your Ball, perhaps you can take comfort from knowing that the Prince Regent experienced a similar disappointment back in 1813! We'll leave this investigation there, if you have any observations to share, do please Contact Us, we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved