|

Paper 32

Copyright Disputes between London's Dance Publishers, 1810s

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 29th September 2018, Last Changed - 7th March 2021]

London's music sellers of the Regency period were increasingly aware of copyright as a mechanism to secure their own competitive advantage. We've investigated the single most interesting dance related dispute in a previous research paper, in this paper we'll consider the testimonial writs from some further cases, and consider what can be learnt about the dance industry of the 1810s from them. A previous paper investigates the 1818 dispute between the music shops of John Charles White (of Bath) and Christopher Gerock (of London), it offers a general introduction into the social dance industry of the 1810s, you might like to read it before continuing here; this paper extends that earlier theme by considering several additional historical complaints between publishers concerning social dance music.

List of Disputes

I've been able to study surviving information from several different copyright disputes of the 1810s, most of which has been preserved by the UK's National Archives. None of these records are complete, but they're fascinating even in their inconclusive state.

The disputes we'll consider are:

In each case the dispute is primarily related to the music for social dancing, though other issues are sometimes referenced. I know of little evidence for copyright disputes between dance publishers prior to the 1810s (excepting the disputes involving John Walsh in the early 18th century); this burst of legal activity is therefore indicative of a wider social change that was enveloping the entire dance industry, we'll investigate those changes in this paper. One minor action is known to have been pursued in 1806 at the Court of Chancery involving a tune from a ballet named Laurette that was adapted into a Country Dance, that dispute failed when the ballet in turn was found to have reused music from an even older source (British Press, 13th February 1806); other similar disputes may have been tried, the industry was evidently starting to consider the question of copyright for dance tunes in the early 19th century.

Country Dance publishing in Britain began in 1651 with publication of the first edition of John Playford's The English Dancing Master; for roughly 60 years the Playford family held an effective monopoly on Country Dance publishing in England, with very little competition from rivals. Over time the infrastructure for printing improved, a broader range of music sellers began publishing social dances. By the mid 18th Century there were several prominent publishers, and by the early 19th century there were dozens of active publishers; as competition between publishers increased, the need to secure competitive advantage became more important, with recourse to law where necessary. The legal disputes between publishers offer some of the most detailed insights into the activities of the dance publishing industry that I know of; that evidence is fundamentally annecdotal in nature, but with six different cases to study there's sufficient information for us to infer some general trends, even if the outcomes aren't always known.

I should also offer a statement of caution - I'm not an expert in historical legal terminology; if you're able to correct any of my inaccuracies in this commentary (or otherwise share additional information), do please Contact Us. With that proviso stated, let's take a look at the material.

The Pattern of Evidence

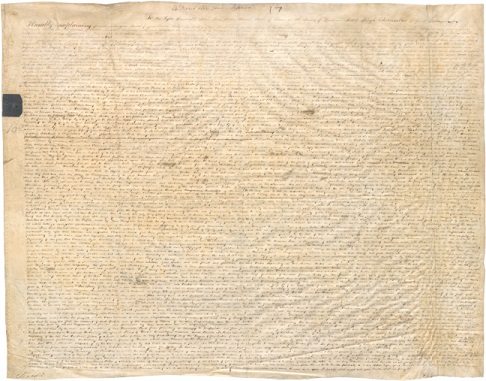

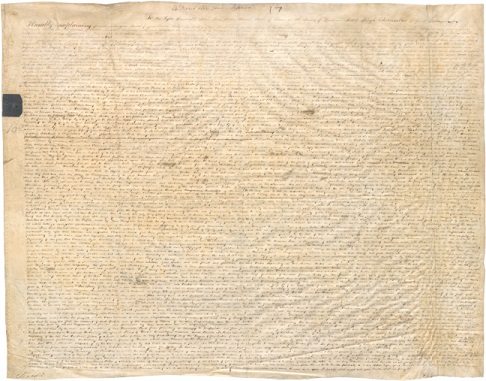

Figure 2. Birchall's writ of complaint, 1812. Image © the National Archives.

The general pattern to the surviving evidence involves both a writ (or bill ) of complaint, and a writ of response; the complaint is issued by the party who considers themselves to be injured (they're the plaintiff ), the response is issued by the defendant. The documents tend to be lengthy and repetitive, they feature compound words (such as hereinbefore , thereunder , notwithstanding , etc.) and legal terminology; there's also a striking aversion to punctuation. Individual sentences might run-on to many hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of words. I imagine that the legal copy-writers were paid by the word!

Transcribing the documents has been a frustrating process and the results are difficult to consume. The documents are, in some cases, amended with extra information or crossing out of existing text, some are damaged, all are sufficiently repetitive that it's easy to accidentally misread sections. A synopsis of each document will be offered rather than a pure transcription (this allows us to gloss over the portions of the documents that have defied interpretation); punctuation has been added to any quotations, including commas and stops, despite a general absence of punctuation in the source documents. The original documents are available for study from the National Archives should you wish to see them for yourself. Figure 2 shows the writ issued by Robert Birchall in 1812, it's approximately of average length at around 4200 words.

In some cases we have surving comentary from other sources that independently describes the disputes, that information is referenced where available.

1. Robert Birchall versus Charles Wheatstone, 1812

The National Archives preserve the writ of complaint issued by Robert Birchall in March 1812 against Charles Wheatstone (see Figure 2). Birchall was the proprietor of one of London's major music shops, he traded in serious musical compositions, rarely venturing to sell social dance collections. Wheatstone ran a less prominent business, we've written about him before; his business had been steadily growing since around 1790, by 1812 he was becoming recognised as a more serious supplier of music and musical instruments.

Summary of the Complaint

Birchall declared that in 1805 Daniel Steibelt had composed a ballet called La Belle Laitiere, or Blanche Reine de Castille; Birchall bought the rights to it for £100. He also declared that in 1808 F. Fiorillo had composed an accompaniment to a ballet called Le Marriage Secret ou Les Habitants du Chene; Birchall bought the rights to it for £84. Birchall had published both of these compositions and considered them to be valuable, they were also performed on stage.

He alleged that Wheatstone had pirated parts of these two compositions for use in Country Dancing collections. Specifically:

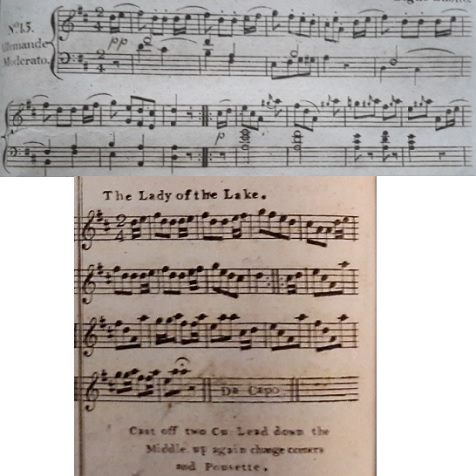

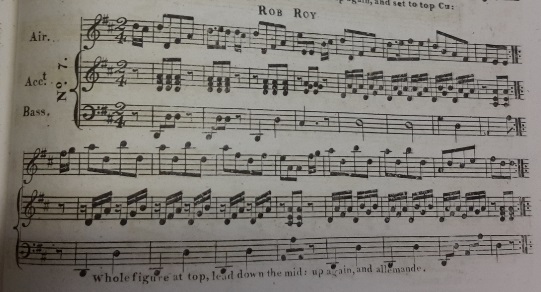

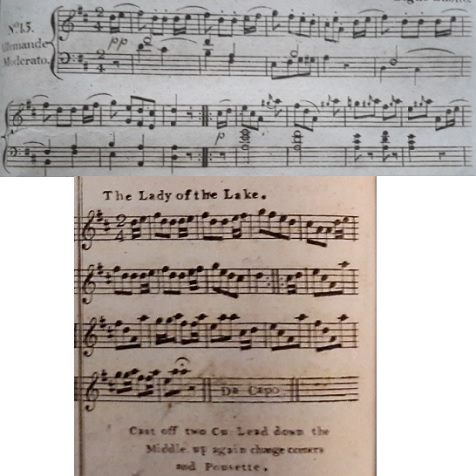

- The Lady of the Lake - Birchall claimed that the entire tune of this name in Wheatstone's c.1811 6th Book was copied from a passage within Le Marriage Secret named No 13 Allemande Moderato (see Figure 3).

- La Belle Laitiere - Birchall claimed that this tune from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 A Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 1st was copied from a passage in his own

La Belle Laitiere, or Blance Reine de Castille named Shawl Dance by Madame Parisot. Birchall claimed that

certain trivial and colorable alterations had been made to his music in order to disguise the source of the tune.

Figure 3. The start of Birchall's No 13 Allemande Moderato, from Le Marriage Secret 1808 (above); and The Lady of the Lake, from Wheatstone's Elegant & Fashionable collection of Country Dances for the Year 1812 (below).

Birchall went on to assert that he had made frequent requests that Wheatstone should cease copying and printing these tunes, and to account for the profits made from those tunes. Birchall claimed that the tunes that were copied were the most popular parts of the larger works, and that his damages in lost sales were therefore quite considerable.

Birchall then explained in the writ that Wheatstone himself had claimed that Birchall was not the proprietor and rightful publisher of the aforesaid several books or compositions hereinbefore mentioned and that he hath not the sole copyright thereof and that the same are not original compositions ; Wheatstone was understood to have believed the tunes to have been composed by third-parties, that he had legitimately acquired the rights to print them, and that there was very little money made from publishing them anyway!

Birchall however charges the contrary thereof, and that the said confederates hath sold large quantities of the said books or numbers, and hath made very considerable profit by selling the said pirated pieces of music contained therein . It is then requested in the writ that Wheatstone and his confederates should full true perfect and distinct answer make, to all and singular, the matters aforesaid to the best of their several and respective knowledge rememberance information and belief ; or alternatively explain by what right he believed he could print the tunes (that is, to proove that the composers named by Birchall were not the true composers of the tunes, or that they had licensed the music to him before selling it to Birchall, or similar).

Analysis

There is no record of a response from Wheatstone, he evidently settled the issue out of court. It's possible that Wheatstone really did purchase the tunes from third parties in good faith; it's also possible that he knowingly pirated them, or perhaps most likely, that he hadn't given the issue of copyright a single thought. Country dance publishers regularly featured stage music within their collections at this date, the industry hadn't considered it to be much of an issue in the past; a copyright dispute may therefore have been something of a surprise. Wheatstone paid a settlement to Birchall.

Figure 3 depicts the start of the passage that Birchall claimed had been copied from Le Marriage Secret, and also the equivalent tune published by Wheatstone (though not the edition referenced in the writ of complaint). The music is clearly the same with only minor modifications, Wheatstone had no defense.

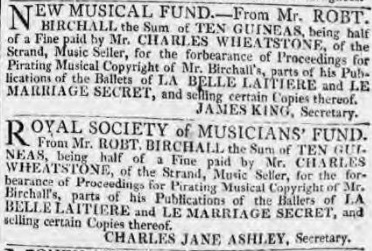

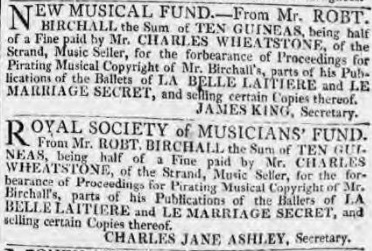

Birchall, perhaps in an effort to deter further such piracy, published a record of his victory in the Morning Chronicle for 20th July 1812 (see figure 4); he took the interesting step of donating half of his damages to the Royal Society of Musicians' relief fund, thereby providing an excuse to reveal the full damages as twenty guineas. The Chronicle recorded a donation From Mr Robt Birchall the sum of ten guineas, being half of a fine paid by Mr Charles Wheatstone, of the Strand, Music Seller, for the forbearance of proceedings for piratical musical copyright of Mr Birchall's, parts of his publications of the ballets of La Belle Laitiere and Le Marriage Secret, and selling certain copies thereof . There were two such announcements printed contiguously, it's unclear whether the money was split between two different funds, or whether Birchall was so keen to have his victory publicised that it was printed twice. Either way, the announcement is likely to have had an impact on the wider music publishing industry - country dancing tunes were no longer implicitly within the public domain, and Robert Birchall was not to be messed with!

Figure 4. Birchall's victory recorded, Morning Chronicle, 20th July 1812. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Wheatstone probably went further than simply paying Birchall damages. Two editions of his c.1806 A Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 1st are known to exist; the later edition contains many changes compared to the first edition, it may have been issued in 1812 as a consequence of this dispute. The later edition, amongst other alterations, removed the problematic La Belle Laitiere tune. I've yet to locate the edition of Wheatstone's Lady of the Lake mentioned in the writ, it's not located within either of the two surviving copies of Wheatstone's c.1811 6th Book that I've studied - it was likely replaced for the later reprints. Figure 3 shows a different edition of the same tune published by Wheatstone for the year 1812.

2. Button, Whitaker & Beadnell versus James Platts, 1814

The National Archives preserve both a writ of complaint issued by Button & Co. in December 1814, and also a writ of response from James Platts issued in February 1815. Button, Whitaker & Beadnell were publishers of a copious collection of Country Dance publications throughout the 1810s, we've written about them before; James Platts was a musician and publisher who had been composing and publishing music since before 1790.

Summary of the Complaint

Samuel James Button and his partners (hereafter simply Button & Co. ) declared that John Whitaker, one of the partners, had composed in 1810 the tune of the comic song Paddy Carey's Fortune or Irish Promotion. Their business owned the song; at time of publication the business was named Button & Whitaker, but by the time of the complaint they were Button, Whitaker & Beadnell, the rights to the song were co-owned by all three of them. They alleged that James Platts had in 1814 printed the music of the song in his 41st collection of Platts original and Popular Dances, with some trifling variations. They claimed that Platts had sold many copies of his publication at a shilling per copy, and that he refused to accept that he had no right to do so.

They asked for Platts to be forbidden from continuing to sell their tune. They also asked for him to explain why he thought he had the right to sell the tune, and how many copies had been sold; they further alleged that the trifling variations in the Platts version of the tune were introduced in an attempt to avoid detection.

Summary of the Response

Platts denied that Whitaker was the composer of the tune, he instead believed the tune to be a minor variation of a certain old piece of music or tune called the Almanack Maker composed by a Mr William Reeve for and sung in the Opera of the Lake of Lausanne . The first four bars of the tune he thought to be identical, and that they were at the heart of the melody. He alleged that Whitaker had knowingly copied the older tune, deliberately adding variations in order to obscure his own reuse of that older tune.

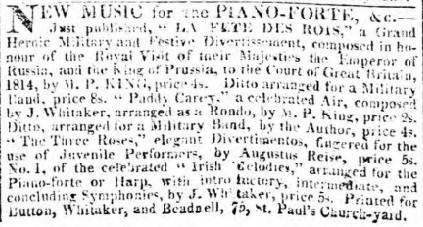

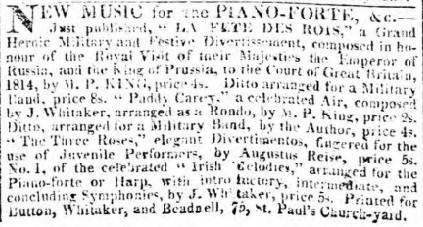

Figure 5. Advertising Paddy Carey, Morning Post, 2nd August 1814. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Platts went on to describe his series of Platts' Original and Popular Dances as a monthly publication, and that the 41st number was issued in or for the month of August one thousand eight hundred and fourteen ; he acknowledged that he had derived his own Paddy Carey from that of Button & Co., but that it was an abridgement - the original being 62 bars of music, the country dance only 16 bars. He added that this Defendant believes that the said Melody or Dance, so published by him as aforesaid, has always been considered by musical men as a fair and bona fide abridgment of the said piece of Music .

Platts admitted that he had copied Whitaker's song, but he denied it to have been composed by Whitaker, and added that the variations he'd introduced were necessary in order to abridge the song into a dance.

Platts admitted to having sold between 180 and 200 copies of the 41st number of his series; three fourths whereof, or thereabouts, he this Defendant hath sold to the Trade at the rate of Eight pence per Number, and the remainder thereof has been sold by this Defendant at the rate of One Shilling per Number ; he added that as the publication contained 6 tunes, most customers bought it out of interest in the other tunes. He further asserted that as Whitaker had fradulently claimed to be the original composer of the tune, Button & Co. had no right to it, and this defendant insists and hereby humbly submits that he hath a good right and title to print and publish the said Melody or Dance, so published by him as aforesaid .

Analysis

The tune of Paddy Carey was in the process of becoming popular in late 1814, sufficiently so that there was likely to be a financial interest for whoever could monopolise sales of the tune.

Whitaker's song had been performed on stage since at least as early as June 1810; a record in The Morning Post for 26th June 1810 mentions a performance of The Beggar's Opera, and that in the course of the evening a variety of songs will be introduced including Irish Promotion, or Paddy Carey's Fortune , the music by Whitaker . By 1813 Button & Whitaker were advertising (Morning Chronicle, 22nd October 1813) The Popular Irish Song, PADDY CAREY, composed and arranged (in Parts) for a Full Military Band, by John Whitaker, Price 4s . Less than a year later they were advertising (The Morning Post, 2nd August 1814, see Figure 5) Paddy Carey, a celebrated Air, composed by J. Whitaker, arranged as a Rondo, by. M.P.King, price 2s; Ditto, arranged for a Military Band, by the Author, price 4s. . These two publications were registered for copyright purposes in July and August of 1814. The New Monthly Magazine reviewed the Rondo in 1814, they described the Air as one of the most sprightly and pleasing we have heard in a long time . By February 1815 (Liverpool Mercury, 10th February 1815) it was popular enough that a regional newspaper could advertise that The Horse Alfred will dance a Pas Seul, to the tune of Paddy Carey .

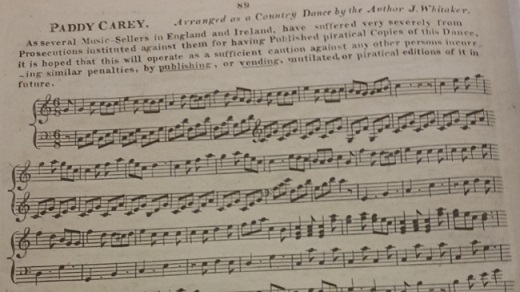

Button & Co would go on to issue their own arrangement of the Paddy Carey tune for Country Dancing, with an elaborate arrangement of figures by Thomas Wilson in the 1816 30th Number of their Selection of Dances, Reels & Waltzes (see figure 6, we've animated an arrangement of it here). They had previously issued a tune named Paddy O Carey in their Thompson branded Country Dancing collection for 1811 (with figures by John Hopkins); this earlier tune seems to have warranted little notice, I can discern no similarity between the tunes other than the name. The new tune would go on to be popular throughout the 19th Century.

Platts' defense is rather interesting. He argued that Whitaker had himself copied the core part of the tune from an earlier work, that abridging a song into a dance was an acceptable thing to do, and that he'd hardly made any money from doing so anyway. He identified the original source as an air from the 1805 Opera Out of Place; or, the Lake of Lausanne, with music by William Reeve. The air in question, Almanak Maker was a popular tune; it was still remembered in 1816 when The Theatrical Inquisitor reviewed the opera, and it triggered a disappointing review in 1808 when The Universal Magazine of Knowledge and Pleasure found another of Reeve's Songs to be a mere copy of it. Whitaker clearly believed his tune to be a new composition, but Platts argued otherwise.

It's uncertain how the case proceeded at court, but Platts is known to have lost (a subsequent dispute mentions Platts' failure, see below; a later edition of Platts' 41st Number replaced the problematic tune with the defiantly named Paddy Carey's Ghost). James Platts went on to issue two fresh writs of complaint of his own; he had his own archive of tunes, so he retaliated in kind - we'll come to Platts' counter claim shortly. Button & Co published their own Country Dancing arrangement of Paddy Carey in 1816 (see figure 6), with the following note attached: As several Music Sellers in England and Ireland, have suffered very severely from Prosecutions instituted against them for having Published piratical Copies of this Dance, it is hoped that this will operate as a sufficient caution against any other persons incurring similar penalties, by publishing, or vending, mutilated, or piratical editions of it in future . It's unclear whether there were other prosecutions involving this tune, their statement may have involved a degree of hyperbole; Whitaker had taken an action against Maurice Hime in Dublin in 1815 over piracy of certain other songs, the Irish reference probably related to that action.

3. James Platts versus Button, Whitaker & Beadnell, 1815

The National Archives preserve both the writ of complaint issued by James Platts on the 6th June 1815, and the writ of response issued by Button & Co. on the 20th June 1815. This complaint is arguably a continuation of the previous action, only this time Platts was seeking redress. The chronology is further complicated by an amendment to the complaint dated to the 12th July 1815; it seems that Platts was a little too hasty in issuing his complaint, he made some unfounded accusations and had to amend his complaint to correct them (after having read his adversaries reply). We have written about this dispute before.

Summary of the Complaint

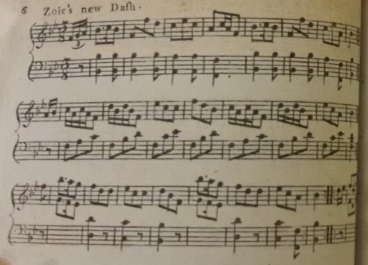

Platts stated that he had either composed or purchased several popular Country Dancing tunes that had subsequently been republished by Button & Co without his authorisation. In 1797 he composed The Zodiac or Zoics New Dash (see figure 7); in 1809 he composed Michael Wiggins and purchased Himley Park from Henry Nicholson for a valuable consideration , and also Ferne Hill or the Tank from Lady Ashbrook; and in 1814 he purchased The Saxon Dance from Mr Bohmer, also for a a valuable consideration . He also complained about a tune called General Kutusoff, though this tune was removed from the writ in the July refresh of the complaint.

Platts listed the publications in which he'd initially issued these tunes; then listed the Button & Co. publications in which the same tunes could be found (sometimes with minor variations or name changes). He charged that all such variations as have been so made by the said Defendants, as well in the names of the said Dances respectively as in the music of the same, have been studiously made by them merely for the purpose of concealing the fact of their having been fraudulently taken from your orator's said compositions, that they might appear as original compositions of themselves, the said defendants .

Platts claimed that a great many copies of the tunes had been published, and that Button & Co. refused to acknowledge his ownership of the tunes. Platts wanted them to be blocked from further publication of the tunes that he owned, and that the sales and profits from those tunes should be enumerated and restored to him.

Summary of the Response

The response addressed each tune in turn.

- In 1806 Button & Purday had printed The New Dash or Zoiac

which these Defendants believe was an old Dance published by several other Music Sellers as much as ten or fifteen years ago including Goulding & Co. amongst others. They had sold 950 copies in their 4th collection (see figure 8), and believed it had been published by many other vendors before Platts claimed to have composed it.

- In May 1811 they published Henley Park in their 16th collection, a tune they believed had previously been published by numerous other vendors including Messieurs Halliday, Cahusac, Wheatstone, Bland and Weller. They didn't believe the tune to be an original composition as it appeared to be derived from a song called You see Sir I'm in haste, and the rest from a song of Charles Didbin's that started with the line

About a hundred years ago . At the time that they published the tune they were ignorant that it was claimed as property by any Person , they had printed 900 copies.

- In February 1812 they published The Tank in their 18th collection. They sourced their copy from

Mr George Walker of Portland Street it was given out by him as the composition of Mr Reeve of Bury in Suffolk . Many other publishers had also published it, including Walker himself; they had printed 1000 copies. They believed that Martin Platts (James Platts' brother, a fellow musician and publisher) had brought it from the continent about four or five years since and it was by a well known amateur . We've studied The Tank in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more of this tune.

- In February 1813 they published Michael Wiggins in their 21st collection. They'd copied it from a Wheatstone publication, though they believed it to be widely published by other music shops too. They'd printed 800 copies, up until the time of their own action against Platts over Paddy Carey; they became aware that Platts claimed ownership of the tune at that time, and

in the hope to settle amicably with the complainant respecting the song called Paddy Carey (the invasion of the copyright as to which they could not permit) desisted from selling the said Dance called Michael Wiggins . They replaced it in their 21st collection with another dance called Calder Fair, and destroyed the plates of such last mentioned Dance which however these Defendants say they did not do from any conviction of the copyright of such said Dance being really in the complainant, but solely for peace sake and to prevent the complainant in the then dispute between them taking umbrage at the Publication . They went on to add that they considered the tune to actually have been adapted from one of Whitaker's tunes named Young Quaker. We've studied this tune in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

- In February 1813 they also printed Prince Kutusoff in their 24th collection. They observed that their tune had no content in common with Platts' General Kutusoff; their tune was sourced from

Mr Nightingale organist to the Foundling Hospital by way of Mr Bates the Engraver , and they had printed 900 copies. They subsequently learned from Mrs Arch one of the firm of Halliday and Company that such last mentioned Dance was claimed as their Property , so they removed it in favour of The Saxon Dance, a tune it transpired that Platts also claimed to own. With respect to General Kutusoff, they considered themselves quite strangers to that Dance and Tune . Platts (we might infer) had not compared the two similarly named tunes to see whether they shared the same content or not! He went on to remove this tune from the complaint. We've studied this tune in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

- They had sourced their version of The Saxon Dance from

Messieurs Clementi and Company without knowing it was claimed as Property by any one , and had printed 1000 copies. They didn't consider it to be an original tune however, it was instead

in part taken from an old foreign air called Ah Ca Ira and also a song composed by Doctor Arne. They further belived that Platts had sometime in the present year One thousand eight hundred and fifteen, a considerable time after these Defendants and other Music Sellers had printed and sold it (and not in or about the year One thousand eight hundred and fourteen as in his Bill untruly alledged), the said complainant did purchase or pretend to purchase for some, but they know not what, consideration of Mr Bohmer in the said Bill named (whom Defendants believe to be an alien in this country) the Music of the said Dance called The Saxon Dance . That is, they believed Platts had no financial interest in the tune at the time that they published it, even if he had since acquired rights to it; and as the product of a foreign national, it was unclear whether the tune was subject to copyright protection in England at all. We've studied this tune on another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

They further explained that they have sold or caused to be sold a great many copies of the respective numbers of the said works at the rate of one shilling per copy as also a great number at eight pence and six pence per copy to the trade. Also, in the course of their said business they have several hundred customers who received music from them upon sale or return, and most of whom have in that manner received the several numbers of their selection of dances and whose accounts are not yet rendered . Therefore they were unable to set forth a full true and particular (or any) account of all the copies of the said several numbers of the said works.

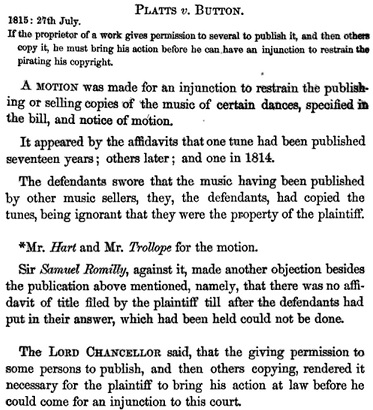

Analysis

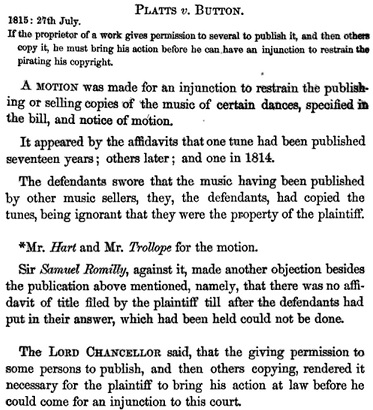

Platts' case was rejected on the 27th July. The Chancery records (see figure 9) mention two factors in this decision: firstly, the defendants had copied the tunes, being ignorant that they were the property of the plaintiff ; and secondly there was no affidavit of title filed by the plaintiff till after the defendants had put in their answer, which had been held could not be done . Platts had been too slow to prove that he owned the copyrights, and (as the tunes were routinely published without a copyright statement) Button & Co. were not to know that they the tunes were property. Platts didn't advertise his ownership of the tunes sourced from Bohmer until April 1815 (Morning Post, 7th April 1815); it's likely, as the defense suggested, that Platts had purchased the publication rights shortly before that date, knowing that the tunes were already widely circulated, and specifically for retaliatory use. It didn't help his case.

Figure 9. Chancery records for Platts versus Button & Co., from Reports of Cases Decided in the High Court of Chancery, Volume 10, 1855

These issues didn't entirely destroy Platts' case, but the complications would need to be decided at law before the judge could issue an injunction. There was also a humorous aside in the courtroom (documented in The Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser for 28th July 1815) in which the judge queried what a waltz was, we've described this exchange before.

Platts didn't completely waste his time in this action however, he had submitted almost the same complaint against Charles Wheatstone on the 12th July 1815 (the same day that the writ of complaint in this case was amended); he still had some time to learn from his mistakes before that second dispute was tried.

Various fascinating details emerge from the Button & Co. testimony. For example, we learn that they were routinely printing between 900 and 1000 copies of their simple dance collections, and they sold hundreds of copies to the trade on a sale-or-return basis; tunes were passed to music publishers almost by word of mouth, and copying was both routine and normalised; we also discover that the origins of dancing tunes can be complicated, they're routinely constructed from fragments of other tunes. The judge in this case avoided having to investigate the origins and creative value of these tunes in any detail, the issue of complexity and creativity within dancing tunes would return to be investigated in the later disputes brought by John Charles White.

One further observation that might be made is that Button & Co. come across, at least to me, as a legitimate business who were attempting to do the right thing. They gave what appear to be honest answers with respect to their sales (the same is less plausibly true for some of the other Defendants), they voluntarily ceased selling any tunes discovered to be subject to copyright, and they produced a lot of new music in-house. We'll see in the subsequent cases that they represented the interests of both music-sellers and music-composers; they were also, from my modern point of view, the vendors of the highest quality country dancing publications the industry had ever known. More can be read about their contributions to country dancing in a previous paper.

4. James Platts versus Charles Wheatstone, 1815

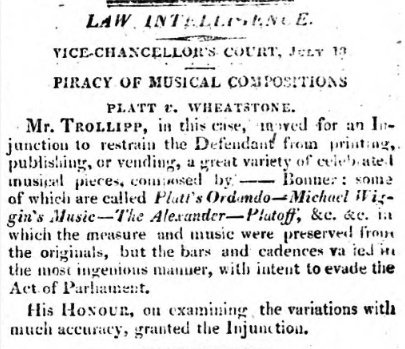

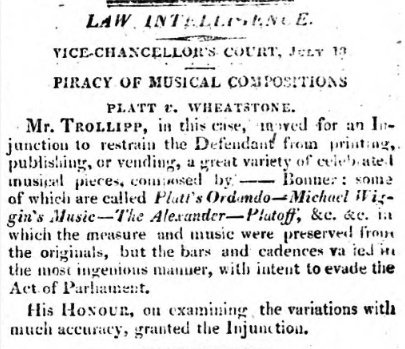

The National Archives preserve both the writ of complaint issued by James Platts on the 12th June 1815, and the writ of response issued by Charles Wheatstone on the 11th October 1815. The complaint has much in common with the complaint Platts issued against Button & Co., though tailored for a different target. An initial injuction was issued against Wheatstone on the 13th July 1815 (The Globe, 14th July 1815, see figure 10).

Summary of the Complaint

Much of the preamble to the complaint was in common with the preceeding case, with Platts claiming ownership of the same collection of six tunes. This dispute added references to three further tunes; in 1814 Platts had purchased rights to Arabella from Mr Bohmer, in April 1815 he'd purchased rights to The Alexander, also from Mr Bohmer, and in 1813 he had himself composed a tune called Miss Platoff.

Platts alleged that Wheatstone had published copies of all nine of these tunes, with trifling variations, and without permission. He wanted Wheatstone to account for his actions, and to be restrained from further publication of his tunes.

Summary of the Response

Wheatstone addressed each of the accusations in turn.

Figure 10. Law Intelligence, from The Globe, 14th July 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

- Wheatstone admitted to having published 150 copies of the tune Michael Wiggins over five or six years in the 1809 19th number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances; he claimed to have done so

with the full knowledge of the said complainant, yet the said complainant did not at any time represent to this defendant that he, the said complainant, had any copyright therein ; and had this defendant known or suspected that the said complainant possessed any copyright in the said tune he would not have printed or published the same . Wheatstone then named many other publishers who had also issued the tune and stated that it was considered as common property . He further believed the tune to be derived from several old songs including A Bachelor leads an easy life , and also from a dance called Young Quaker (which is the same tune that Button & Co mentioned in their equivalent defense).

- Wheatstone acknowledged that he had published 200 copies of The Zoick in the 12th number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances and also in a collection he'd issued around 1797; he copied it

from a printed copy of the same tune bearing the same name and which was printed and published by Messrs J. and W. Lintern of Bath, as this defendant believed, upwards of twenty years ago , he thought the Bath copy predated the 1797 date at which Platts claimed to have composed the tune. He added that he hath ever since continued to sell the same without any copyright being claimed therein by any person or persons whomsoever , as had many other publishers, and he doth not believe that the said complainant hath any copyright in the same .

- In the case of General Kutusoff, Wheatstone had received the tune in manuscript form from a Mr Reynolds (a musician of Bath) in March 1814;

whereupon this defendant soon afterwards printed and published the same, and he believed at the time (and until very lately) that he this defendant was the first printer and publisher thereof . He explained that he had since learned that Skillern & Challoner had printed it in 1813, and that many other publishers had also issued it. Furthermore, not one of the copies which this defendant has seen bore the name of the said complainant or represented that the same complainant, or any other person, had or claimed to have any copyright therein . He thought that the tune was not an original composition, it was instead derived from an old opera the music of which this defendant perfectly recollects although he does not recollect the name . Wheatstone printed around 200 copies of the tune in the 33rd number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances.

- Wheatstone acknowledged that he had printed around 150 copies of Miss Platoff in the 28th number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances, and also in his annual collection of 24 Country Dances for the year 1815. It had previously

been printed and published by almost all the music sellers in London and was considered as property wherein no person claimed any copyright . Once again he thought the tune had been constructed from fragments of older tunes (which remained unnamed), and that he wouldn't have published it had he known it to be under copyright.

- Wheatstone had published 150 copies of The Tank in his 25th number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances. Wheatstone rejected the idea that it

was composed by one Lady Ashbrook , believing instead that it was a Russian tune brought to England around the year 1800; he also believed that a version of the tune had been brought from Germany c.1810 by Mr Louis Spindler, late of the German Legion , and that it had been played by the Band at Ipswich upwards of five years ago, and the same tune was afterwards arranged as a rondo by Mr Harrington of Bury Saint Edmonds, and was first printed and published by Mr Gray of the same place . Moreover, Mr Gray offered the original plates from which the same had been printed by him to this defendant for sale six months ago, but this defendant declined to purchase the same inasmuch as he considerd the same to be of little or no value, the said dance having been printed and published by almost all the music sellers in London .

- In the case of Henley Park, 150 copies had been published in the 20th number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances. He

printed the same from a manuscript copy thereof given to him by a musician at Bath in the year one thousand eight hundred and ten, who represented to this defendant that the same had been composed as a dance for the Bath Rooms in that year . It had gone on to be published by almost all the music publishers in London , and is considered as common property . He offered the same theory of derviation for the tune that Button & Co had offered in their own defense.

- Wheatstone had included the tune Arabella in his collection of 24 Country Dances for the year 1815, and printed around 300 copies. He didn't know that it was subject to copyright, and it was widely published by other music sellers.

- Wheatstone had published 200 copies of The Saxon Dance in Wheatstone's selection of elegant and fashionable Country Dances, Reels Waltzes &c. He sourced it

from a publication thereof under the same name and title by Mr Dale of Cornhill without knowing that it was claimed as property by anyone . It had been published by many of the major music sellers, and Wheatstone believed it to be derived from several older tunes.

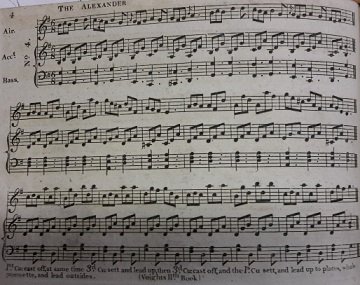

- With respect to The Alexander, Wheatstone was unfamiliar with Platts' version of the tune, but it was

shewn to this defendant by the solicitor of the said complainant, as the rondo called The Alexander, published by the said complainant, yet this defendant hath not examined the same . Platts alleged that Wheatstone had copied the first 24 bars of a much larger work, the rights to which Platts owned. Wheatstone responded that this defendant craves leave to refer to the said publications themselves, when the same shall be produced to this honorable court (this defendant not having examined the same) . Wheatstone did admit to having printed 200 copies of a certain piece of music styled The Alexander , a popular dance arranged as a rondo for the piano forte by Augustus Voight , and a further 200 in the 33rd number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances. Wheatstone asserted that his version of the tune was delivered to him in manuscript, in or about the month of March now last past, by Mr Bevan, as a new air and which at that time had not been printed by anybody, and the same was afterwards arranged as a rondo by the said Augustus Voight for this defendant . Moreover, he hath been informed by Mr Mitchell (music seller in Bond Street) and therefore believes it to be true, that the said complainant declared to the said Mr Mitchell that he, the said complainant, had no copyright in the Alexander printed and published by this defendant, but was only endeavoring to frighten this defendant . Figure 11 shows another tune called The Alexander published by Wheatstone & Voight; it's not the rondo directly referenced in the dispute, but was presumably published under the same name shortly thereafter. We've studied this tune in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Wheatstone went on to explain that he had sold copies of his various publications at the listed prices, but also a great many copies of the same at less than half of such rates . Moreover, in the course of his business he hath several hundred customers who received music from him upon sale or return, and most of whom have in that manner received the several numbers of the said works, and whose account are not yet rendered .

Analysis

Wheatstone took four months to produce his response, during most of which time he was under an injunction to cease publication of the controversial tunes. The response he eventually submitted was somewhat similar to that from the earlier case of Button & Co., he seems to have been familiar with their defense. He emphasised the very issues that had proven to be the most troublesome to Platts in the earlier case: that the tunes were widely printed without a copyright notice, universally considered as unowned, that the origins of tunes were often quite complicated, and that Platts' ownership of the tunes was subject to dispute. He also (I suspect) attempted to limit his risks by claiming an implausibly small distribution of the various tunes, and very little profit therein.

Platts probably was honest in believing that he owned the copyrights to the various tunes; it is true that they were widely printed, but in most cases the earliest edition I can discover is that of Platts himself. It may also be true that Wheatstone believed the tunes to be unowned. Wheatstone routinely copied tunes from other publishers; this seems to have been the general practice amongst country dance publishers, unless there was an explicit copyright statement attached to the tunes to prevent it.

I don't know the outcome of this trial but I suspect that Wheatstone lost. He appears to have ceased publication of two of his regular Country Dancing collections at or around the date of this trial; the 33rd number of Wheatstone's Occasional Repertory of Dances may have marked the end of that series, and I know of no further editions of his 24 Country Dances for the Year xxxx publications after 1815. This seems unlikely to have been a coincidence; even if he had won at court he may perhaps have calculated that the risks of publication were greater than the rewards. He continued to publish Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances in collaboration with Augustus Voigt for a few more years... that is, until he was once again accused of copyright infringement in late 1818 (see below). Figure 11 shows a tune from the surviving publication series which matches the name of one of the disputed dance tunes.

James Platts was also to suffer. He was declared bankrupt in 1816, though he evidently recovered and continued publishing dance music into the early 1820s.

5. John Charles White versus Christopher Gerock, 1818

This trial is different to the preceeding cases in that I've been unable to study any formal documentation from it. Most of the surviving information is derived from the courtroom reports issued in the press, something we've extensively documented in a previous paper. A synopsis of the available information will be offered here, but it's worth referring to our other Paper for more complete information. The case was tried in December of 1818, the plaintiff was White's of Bath and the defendant was Gerock's of London.

Figure 12. More Miseries of Modern Life: Being nervous and cross examined by Mr Garrow, Rowlandson, 1807. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Summary of the Complaint

The Whites of Bath complained that a popular tune they owned named Captain Wyke had been piratically published in London by Christopher Gerock. The tune was a favourite in Bath and immensely profitable, but the sales had collapsed since Gerock had printed his copy of it in London.

Summary of the Response

Gerock admitted to having published 125 copies of the tune, but had not sold many of them; he had received the tune from a Benjamin Payne, a musician from Bath, and believed that several other music shops had published it before he did.

Gerock called upon a whole team of expert witnesses to testify that the tune was not copyrightable by virtue of having been constructed from fragments of several older tunes. John Whitaker of Button & Co. was then brought in by White to assert the counter argument, he stated that the tune was in fact an original composition, and therefore copyrightable.

Gerock's team also offered the argument that a single sheet of music did not constitute a book in law, nor did a manuscript copy of a tune; moreover, the tune was published (and registered for copyright purposes at Stationer's Hall) under a pseudonym. His team further argued that Gerock's version was not a piracy of the plaintiff's work, inasmuch as it materially differed from it, particularly as to the dancing figure accompanying the music .

Analysis

The record of the debates in the courtroom are fascinating. The judge instructed the jury to focus on whether White's tune was sufficiently innovative to qualify for copyright protection, or whether it was something which any person of ordinary industry might cut out from their works and paste together . This defensive argument had been used in several of the proceeding cases, but the trials (at least in Platts versus Button & Co.) had ended without a definitive answer. This time the jury found in favour of White, Gerock was lightly fined.

Figure 13. Cross examination of a witness in a case of Criminal Conversation, 1818. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

This case involved a publisher from Bath taking on the cabal of London publishers, an outsider challenging the status quo. This may have been the first of the actions to determine that a country dancing tune was inherently worthy of legal protection (that may have been determined in Platts versus Button & Co., the record is unclear); it was also the first to offer the dancing figures as being material to the publication, an argument that appears not to have found favour in the court.

It's notable that John Whitaker spoke on behalf of White; he was himself the plaintiff in one of the previous cases, but had also been the defendant in yet another. He had argued against James Platts' tunes being copyrightable by virtue of their having been derived from earlier works, but in this case he argued that dance compositions can be copyrightable despite their similarities to earlier tunes. He perhaps saw White as a kindred spirit; someone who produced new tunes that were of a greater quality than the frankenstein compositions published by much of the industry.

This particular case turned out to be the most significant of the entire collection. It had the potential to be devastating to the whole dance publishing industry; it was widely discussed in the press (unlike the previous cases) and was a resounding victory for White's of Bath. The old certainties about how the industry worked were no longer reliable; popular modern tunes weren't fair game for being copied, they were under legal protection, and the share-and-share-alike mentality of the London publishers would not be a dependable defense in the future. This was only the first of two sister cases, a second trial involving Charles Wheatsone was held a few days later, it was to conclude in much the same way.

6. John Charles White versus Charles Wheatstone, 1818

This trial was a sister case to that of White versus Gerock, it was tried two days after the first case. Once again the only surviving records for it that I've found were printed in the press, they record the events that occured in the courtroom itself.

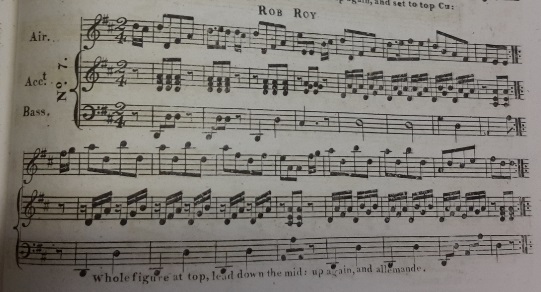

Figure 14. Wheatstone's version of Rob Roy, from the c.1818 Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 13. Image courtesy of the VWML.

Summary of the Complaint

White accused Wheatstone of copying two of his tunes, Lady Caroline Morrison and Rob Roy. These were vended under a cheap form, thereby depriving the plaintiff, who was the author of them, of any advantage arising from the sale of them . White had sold 2300 copies of Lady Caroline Morrison (which was initially called The Wedding Ring) and 800 copies of Rob Roy, the tunes were very popular in Bath. White's father and brother both testified that they were present when the tunes were composed, and John Whitaker once again testified that the tunes were original rather than derived from any existing tunes.

Summary of the Response

Wheatstone's main defense was in the argument that the tunes were not original compositions, but derived from previous works. The judge summarised the case to the jury as follow (Morning Post, 9th December 1818): although to his regret he must acknowledge himself wholly ignorant of the science of music, yet in law he would tell them, that in his opinion, any person taking a number of different bars in music, although every one might previously be found in other compositions, and giving then a new combination, he legally obtained a property in them, to which the law give protection .

Courtroom Drama

An extensive description of the action in the courtroom was published in The British Press on the 9th December 1818. It contains so many fragments of useful detail that it has been transcribed below in full.

Piracy, White v. Wheatstone

This action was similar to that which took up so much of the time of the Court yesterday. The declaration set forth, that the Plaintiff had composed two country dances, called Lady Caroline Morrison , and Rob Roy , in which, by the statute, he had a property for 28 years - but that the Defendant had illegaly pirated them, by which he suffered considerable injury.

Mr SCARLETT, in stating the case, described his client, the son of a music-seller at Bath, as a young man of very great genius. He had devoted himself to the study of music, and had produced several highly-admired country-dances. Two of these, entitled Lady Caroline Morrison and Rob Roy , which were exceedingly popular, and of which, he would prove, the Plaintiff's father had at first sold a great number, the Defendant, a music-seller in the Strand, had thought proper to pirate, by which means the Plaintiff sustained considerable injury. He had, therefore, to protect his property in future, and to recover damages for the loss he had sustained, brought the present action.

The Learned Gentleman then called:

Mr Geo White, the brother of the Plaintiff who deposed that he had seen him compose the two country-dances of Lady Caroline Morrison and Rob Roy .

Mr. John White, father to the Plaintiff, spoke of his son as a most ingenious young man. He had composed 500 country-dances. Of the two which formed the ground of this action, he composed the former in October, 1816, and the latter in February of the present year. Witness sold 4000 of the dance called Lady Caroline Morrison , 2000 in MS and 2000 printed. Of the dance of Rob Roy , he sold 800 in MS.

Mr Munroe proved that he had, by the Plaintiff's directions, caused the two dances to be engraved and printed for his use.

Mr Whitaker, the composer, had compared the edition of the dances published by Mr White with that published by the Defendant. They were precisely alike. The Defendant had evidently pirated them. The compositions were as original as trifles of that kind generally were.

Sir G. Smart looked upon the two pieces to be original, although there might be a similarity, in a particular bar, to some other air. A single bar could not be considered perfect - not less than a phrase, or four bars, could give an idea of a subject. Therefore, though a single bar might be similar to a bar in another composition, he did not think that circumstance destroyed originality.

An old man, who printed the dances for the Defendant, was called to prove the number he had struck off. But, as he could neither read nor write, his evidence was of no service.

Mr SCARLETT said, he had a host of witnesses to call with respect to the originality of the airs, if his Lordship deemed it necessary.

The CHIEF JUSTICE said, the Learned Counsel would have an opportunity of calling any other witnesses he pleased, if the cause in its progress, seemed to call for them.

Mr GURNEY, for the Defendant, regretted that he was not so great an adept in the science of music, as his Learned Friend - but he consoled himself with the hope, that he would, nevertheless, be able to procure a verdict for his client. He would prove, that if the Defendant had committed an error, he had done so unintentionally - since the MS of the dances was handed over to him by a Gentleman whom he would call, and who would state, that neither he nor the person from whom he procured it, were cognisant of any claim set up by Mr White. But the question for the Jury to consider would be, whether these were original compositions? He would call a host of witnesses to prove they were not - that they were compilations from other airs - and, if that were the case, the Plaintiff could not recover. As well might a man say, I have written a fine essay, when he stole one passage from The Spectator , another from The Guardian , and a third from The Rambler , as the Plaintiff in this case lay claim to these dances, as original compositions, if they were only shreds and patches selected from different airs. He then proceeded to call his witnesses.

John Reynolds resides at Bath, and is a musical performer there. He had known the dance called Lady Caroline Morrison , since November 1816, when it was given to him in MS, by a Gentleman. He afterwards performed it in a public assembly. In June, 1818, he gave a copy to Mr Wheatstone. He did not know at the time that the Plaintiff claimed any property in it.

Mr SCARLETT wished the MS to be produced.

Mr CAMPBELL said it had been destroyed.

Witness continued - He recollected the dance of Rob Roy in the last winter, which he also communicated to Mr Wheatstone. He never heard that Mr White claimed any property in it.

Cross-examined - He knew Mr White's music-shop at Bath, and was acquainted with him. He had lived for ten years in Bath, and played at concerts and at the theatre. He did not recollect who the Gentleman was from whom he got the MS. He made a copy from the Gentleman's MS, and returned the original to him. He would not swear that the MS was not marked as White's property. He had seen MS copies of country-dances which were sold by Mr White. Wheatstone occasionally published country-dances, and witness made him a present of two or three. He was not paid any thing for them - neither was his father paid. He never heard that Wheatstone had said he would take his oath before the Lord Mayor that the dances were sent to him amongst others, and that he had paid for them.

Leigh stated, that he was a performer at the Opera-house. Having looked at the country dance of Lady Caroline Morrison , it appeared to him not to be an original composition. The eight first bars were almost precisely the same as a dance in The Forty Thieves . The second part was compiled from The Barber of Seville and Don Giovanni . On examining the dance of Rob Roy , he was decidedly of opinion that it was not original. The first part was built on the air of Will you come to the Bower? . It was the former melody, with a slight variation. It also, in the first part, bore a strong affinity to Astley's Hornpipe . The second part of Rob Roy was made up of bars that had been written a thousand times before. They were quite common. He also held in his hands variations from an old piece, the name of which he did not know, which had evidently been imitated.

Cross-examined - Witness had performed at the Opera for two or three seasons. His instrument was the violoncello. The Barber of Seville came out in the last season. The music was by Rossini. It appeared to him that the music of the country dance Lady Caroline Morrison was in part taken from The Barber of Seville . He did not know the name of the dance in The Forty Thieves , which was also borrowed from - nor could he say what key it was played in. He pointed out the dance in Don Giovanni , from which a part of the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison was selected. A portion of it also resembled an Italian air in The Travellers . Don Giovanni was brought out in the season before last. The music was arranged, in a great measure, by Mr Ayrton. He knew part of the music of Don Giovanni before it was brought out in London. He believed he knew that part which was made use of in the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison , but he was not sure.

Re-examined - There were eight sequent notes, in the second part of Lady Caroline Morrison , precisely the same with an Italian air in The Travellers .

Wm Janson, a Professor of Music, was acquainted with that science for thirty or forty years, and procured his livelihood by it. In his opinion, the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison was not entirely original. With respect to the two first bars, they differed somewhat from the air to which they had been compared. He thought, however, that the person who composed the first part must have been impressed with the recollection of a dance in The Forty Thieves . The bass was nearly the same. The second-part was an imitation of an Italian air in The Travellers . Eight sequent notes were exactly the same as those in the Italian air. The two pieces of music appeared to him to be substantially the same. The dance of Rob Roy was also taken from old music. Part of it was borrowed from a French air, of which it was only a variation. He could not speak positively of any other portion of it.

Cross-examined - Witness had published about 9000 pieces. He did not consider that a person who took the idea of an air from any existing compostition could lay claim to originality of subject - He had never composed a song from a passage in a sonata. He did not think that passages precisely similar were to be found in the works of original composers. Time, he admitted, formed the great difference, with respect to the twelve notes, in the composition of music. If it were not for time, music might be reduced to a mere matter of calculation, according to the notes on the piano or any other instrument. He had seen variations of Rob Roy very like those in the country dance now exhibited. He had sometimes composed variations to old airs, but he did not think that gave him a property in them.

William Wilson deposed, that he had been a Professor of Music for thirty years. He did not consider the country dance of Lady Caroline Morrison to be, by any means, an original composition. The whole subject was taken from The Forty Thieves - but the latter was by far the best dance. The first phrase of the second strain was taken from The Travellers , except the passing or dominant note. The third phrase of the second strain was also taken from The Travellers , except one middle note. The variation of the passing note did not, in the smallest degree, make it an orginal composition. The music he spoke of in The Travellers and Forty Thieves , was older than the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison . He looked upon the dance of Rob Roy as equally destitute of originality. The first strain was entirely taken from the air of Will you come to the bower? . The notes were not precisely the same - but the subject was. A person not skilled in the science, would, if the two airs were played, mistake the one for the other. The ground or fundamental bass both of Will you come to the bower? and Rob Roy , was taken from a French air. With respect to the second part, the first bar appeared to be formed of an air sung by Lingo in The Agreeable Suprise . The second, Of all the flowers , was an adaptation of the air of Sleep on, sleep on, my Kathlane dear! in The Poor Soldier - the third from a country dance, which he himself had composed - and the fourth from a very old air, Prince Eugene's March . He had formed many country dances by compiling, as others had done - but he did not consider them to be original compositions.

Cross-examined - Witness never sold country-dances. He conceived that any person had a right to use compilations of this kind. They did not belong to the individual who only took from different composers. He was acquainted generally with Handel's music. Both in his composititions, and in those of other masters, passages occurred, where the seven notes succeeded each other in regular order.

Joseph Dale had been a composer of music for fifty or sixty years. He did not think the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison was original.

Thomas Bolton, a composer of music, had seen the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison . It was not wholly original - but was formed, in some degree, from an air in The Forty Thieves . The second part was taken from an air in The Travellers . The dance of Rob Roy was not original. It was a variation from a French air. Seven notes out of the eight were borrowed.

Cross-examined - There undoubtedly might be original variations. What he meant to say was, that there were scraps of other compositions in these dances - and that the ground-work was evidently borrowed in both.

This closed the Defendant's case.

Mr SCARLETT called Sir G. Smart again, who stated, that he had written out the two bars of the air in The Travellers , relied on by the Defendant, and they certainly were not similar to those in the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison . The harmony was the same - but the melody, which was every thing in a country dance, was essentially different.

Mr Henry Bishop had arranged the music of The Barber of Seville , for Covent-garden Theatre. He did not think that the second part of the dance of Lady Caroline Morrison was taken from that work. He was of opinion that it was, in a great degree, original.

J.G. Ferrari, a teacher of singing and a composer, had heard the evidence of Sir G. Smart and Mr Bishop, and entirely concurred in it.

Mr SCARLETT was heard in reply. He contended, that all originality consisted in the new combination of old material - and when, by such a combination, a new and striking effect was produced, the person who had succeeded in producing it ought to reap the reward of his ingenuity.

The CHIEF JUSTICE, in addressing the Jury, said, his idea of the law was, that, if a person put together several bars of music, each taken from some old subject, and, by a new combination, produced a new effect, he, in fact, formed a new composition, and acquired such a property in it as was recognised by the Act of Parliament.

The Jury returned a verdict for the Plaintiff. Damages, 5l; costs, 40s.

Analysis

This final case followed the same pattern as the sister case against Gerock, Wheatstone was found guilty for the same basic reasons. Any defense based on the argument that new tunes were constructed from fragments of older tunes was not acceptable in law, new combinations of bars implied a new composition.

It's perhaps worth noting that Wheatstone had once again named his friend Mr Reynolds as his immediate source for music from Bath, Reynolds had previously been identified as the source of the General Kutusoff tune. Reynolds claimed to be unpaid, but as a regular supplier of popular music they must have had some form of arrangement. Wheatstone may have found it convenient to publish popular Bath tunes in London, but that business process was no longer safe.

Well known names from across the social dancing industry had testified both for and against Wheatstone, there was a clear lack of consensus. Many of these people are easily identified: Joseph Dale and Thomas Bolton both ran music shops in addition to composing music; John Whitaker did so too, though he remainded primarily a composer. The names of some of the witnesses in The British Press are slightly suspect; the report consistently misspelled Wheatstone as Whetstone (corrected in the transcript above), and misidentified Louis Jansen as a William Janson; I further suspect that the William Wilson from the report may have been the dancing master Thomas Wilson.

This was the third copyright dispute in which Wheatstone was a defendant. He'd settled the dispute with Birchall, seemingly out of court; it's unclear how the second dispute ended, but he ceased production of two country dancing publication series shortly thereafter; and now he'd lost a third dispute. The timing may be coincidental, but he appears to have ceased production of his remaining country-dancing publication series, Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c., at around this time. It's tempting to assume that he'd given up on country-dancing tunes entirely; he instead focussed on printing new music for Quadrille dancing.

Summary

At the start of the 1810s London had a vibrant dance music publishing industry, popular tunes could be published within collections issued by well over a dozen different music sellers. We've used this extensive overlapping of content as a means to test the influence of the publisher William Campbell in a previous paper; we found, for example, that Campbell had published 96 tunes with names that matched those from the Preston collection, 58 tune names in common with the Cahusac collections, 28 in common with those of Bland & Weller, etc.. If the works of almost any two publishers were compared in this way, significant overlapping content would be found. At the start of the decade such tunes were implicitly considered to be common property, duplication was normal. Some publishers took things a little further; James Platts (for example) probably copied verbatim from the works of Skillern & Challoner between about 1807 and 1809.

Birchall's complaint in 1812 may have been a trigger for change. He (perhaps) took umbrage at one of his serious musical publications being abridged into a mere dancing tune, he fought it and he won. It was already legally established that music was subject to copyright, the 1804 case of Hime verus Dale had found that even a single page song constituted a book under copyright law; Birchall's arguments had little chance of failure under those circumstances. The 1814 dispute between Button & Co. and James Platts was on a similar theme; serious music composed by Whitaker had been adapted into a dance form by Platts, and the court agreed that this was not permitted. James Platts, in retaliation, launched the third trial in 1815, arguing that a half dozen simple country dancing tunes that he owned had been pirated by Button & Co.; he lost that dispute over legal technicalities, but it may have been the first attempt to protect compositions of potentially as little as 16 bars. Platts' argument was tried again in the fourth case, the outcome of which is unclear. The two 1818 complaints from White's of Bath achieved the legal precedent required to confirm that country dancing tunes, no matter how simple, could be considered as works of human genius and fully deserving of copyright protection.

It may be coincidence, but London's social dancing industry was undergoing significant change throughout the late 1810s. Country Dancing fell out of fashion, the Waltz and Quadrille dance forms were taking over. Many of the country-dance publishers who were active at the start of the decade had (as far as can be determined) ceased printing such tunes by the end of the decade: Wheatstone issued his last known collection c.1818, Bland & Weller c.1819; Cahusac c.1821, Skillern & Challoner c.1815; etc.. Publication didn't cease entirely, but far fewer publishers were active at the end of the decade than at the start. It's generally assumed that this change was driven by social pressures in the ballrooms of the aristocracy, but an increased risk of litigation between music sellers may have been a secondary factor. It seems probable that litigation drove Wheatstone from the country-dancing business. The wider industry was also aware of the legal risks, my experience has been that it's easier to find copyright acknowledgements in the dance publications of the late 1810s than in those from the start of the decade.

The problems and risks of unlicensed music printing weren't limited to country-dancing tunes of course. Many of the early quadrille publishers also complained of counterfeit publications; the celebrity publishers took to signing their legitimate offerings as a form of authentication. I'm not aware of any copyright trials being fought over quadrille publications, though records of such disputes may yet surface. White's success in his disputes of late 1818 may have been sufficient to enable publishers to merely threaten each other with litigation, and for disputes to be settled out of court.

I can't prove that the shifting legal landscape forced those music-sellers on the fringes of legality out of business, but the free-for-all mentality of the early 19th century country dance publishers certainly changed; regardless of the cause, things were never the same again. We'll leave this investigation here; if you have any information to add, do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Figure 1. Beware dance piracy. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1. Beware dance piracy. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Birchall's writ of complaint, 1812. Image © the National Archives.

Figure 2. Birchall's writ of complaint, 1812. Image © the National Archives.

Figure 3. The start of Birchall's No 13 Allemande Moderato, from Le Marriage Secret 1808 (above); and The Lady of the Lake, from Wheatstone's Elegant & Fashionable collection of Country Dances for the Year 1812 (below).

Figure 3. The start of Birchall's No 13 Allemande Moderato, from Le Marriage Secret 1808 (above); and The Lady of the Lake, from Wheatstone's Elegant & Fashionable collection of Country Dances for the Year 1812 (below).

Figure 4. Birchall's victory recorded, Morning Chronicle, 20th July 1812. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 4. Birchall's victory recorded, Morning Chronicle, 20th July 1812. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 5. Advertising Paddy Carey, Morning Post, 2nd August 1814. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 5. Advertising Paddy Carey, Morning Post, 2nd August 1814. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 6. Start of the Paddy Carey tune in #30 of Button, Whitaker & Compy's Selection of Dances, Reels and Waltzes, 1816. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 6. Start of the Paddy Carey tune in #30 of Button, Whitaker & Compy's Selection of Dances, Reels and Waltzes, 1816. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 7. Zoic's new Dash, from Book 2nd for the Year 1797, By James Platts. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.11 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 7. Zoic's new Dash, from Book 2nd for the Year 1797, By James Platts. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.11 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 9. Chancery records for Platts versus Button & Co., from Reports of Cases Decided in the High Court of Chancery, Volume 10, 1855

Figure 9. Chancery records for Platts versus Button & Co., from Reports of Cases Decided in the High Court of Chancery, Volume 10, 1855

Figure 10. Law Intelligence, from The Globe, 14th July 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 10. Law Intelligence, from The Globe, 14th July 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Figure 11. The Alexander, from Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 11th, 1816. Image courtesy of the VWML.

Figure 11. The Alexander, from Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 11th, 1816. Image courtesy of the VWML.

Figure 12. More Miseries of Modern Life: Being nervous and cross examined by Mr Garrow, Rowlandson, 1807. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 12. More Miseries of Modern Life: Being nervous and cross examined by Mr Garrow, Rowlandson, 1807. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 13. Cross examination of a witness in a case of Criminal Conversation, 1818. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Figure 13. Cross examination of a witness in a case of Criminal Conversation, 1818. Image courtesy of The Library of Congress.

Figure 14. Wheatstone's version of Rob Roy, from the c.1818 Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 13. Image courtesy of the VWML.

Figure 14. Wheatstone's version of Rob Roy, from the c.1818 Wheatstone's Selection, of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c. Book 13. Image courtesy of the VWML.

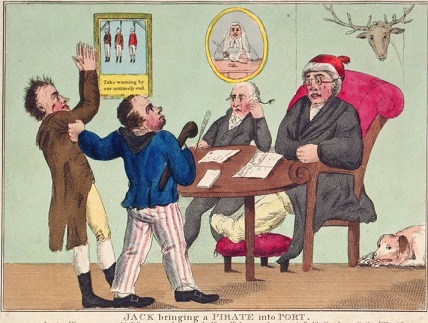

Figure 15. Jack bringing a Pirate into Port, 1804. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich.

Figure 15. Jack bringing a Pirate into Port, 1804. Courtesy of the Royal Museums, Greenwich.

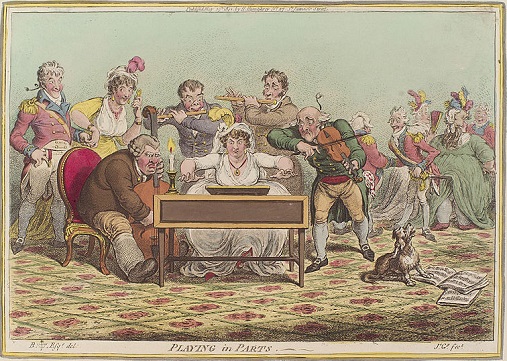

Figure 16. An amateur band, 1801. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.

Figure 16. An amateur band, 1801. Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery.