| Return to Index |

|

Paper 52 A Selection of Balls from 1809Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 27th September 2021, Last Changed - 21st March 2022]This paper continues a theme that we've explored in several previous papers by investigating historical balls held by members of the British aristocracy within a single year, this time we'll study balls of 1809. We'll review the surviving descriptions of five separate balls, in each case we have a brief description of the event that was printed in newspapers shortly after the date of the ball. We'll discover what we can of the tunes and dances named therein.  Figure 1. Woburn Abbey c.1841, home of the Duchess of Bedford and venue for the first ball, image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 1. Woburn Abbey c.1841, home of the Duchess of Bedford and venue for the first ball, image courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

We've previously studied a ball hosted by the socialite Mrs Beaumont in April of 1809, you might like to follow the link to read more of that event. That ball featured the popular country dancing tunes of Michael Wiggins, the Fairy Dance and Lord Cathcart, together with a performance of a Boleros and La Boulangere. We'll discover similarly fashionable tunes of 1809 in this paper. The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

The Duchess of Bedford's BallThe Globe newspaper for the 9th of January 1809 printed a report of the Duchess of Bedford's Ball held at Woburn Abbey (see Figure 1) in Bedfordshire. The Duchess was Georgiana Russell (1781-1853) (see Figure 2), a daughter of the influential Duchess of Gordon. Georgiana had married the Duke of Bedford (1766-1839) back in 1803, the venue was the Duke's family seat of Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire. The Globe newspaper reported (with dance references highlighted in bold):  Figure 2. The Duchess of Bedford, 1807. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. The Duchess of Bedford, 1807. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Woburn Abbey was enlivened on Thursday evening, by the most splendid ball and supper ever given in that noble Mansion. The roads were covered during the day with the carriages of the Noblemen and Gentlemen from the neighbouring seats, conveying their families to the festive scene; a large proportion of the company were also from London. Every arrangement that taste and fancy could devise, and liberality command, was made to give effect to the brilliant scene. The entrance hall and grand stair-case were lighted in the most tasteful and splendid style. The servants, dressed in the state liveries which they wore when his Grace was Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, were arranged to receive the visitors; these liveries are uncommonly superb. The grand Ball-room was decorated with wreaths of flowers, reflecting mirrors, Grecian lamps, &c. &c. The floor was chalked beautifully, in the Grecian style. The most delightful bands of music were provided.

The first dance of the evening was led off by Anna Russell (1783-1857). She was the recently married wife of Francis Russell (1788-1861), he was the Duke's oldest son from his first marriage. Anna was only 2 years younger than Georgiana, the hostess. The Ball was probably held in celebration of their marriage of August 1808. Several curious details emerge from this report, the detail that I find most striking is the reference to Only one tune was named as having been danced at the event, Lauretta. We'll review what is known of this dance shortly.

Hon. Mrs Drummond's Ball Figure 3. The Pillory, Charing Cross in 1808, image courtesy of the V&A Collection.

Figure 3. The Pillory, Charing Cross in 1808, image courtesy of the V&A Collection.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 15th of April 1809 reported on a ball held by the Hon Mrs Drummond. The Drummond family were bankers. Mr Drummond can perhaps (it's a little tentative) be identified as Robert Drummond. Back in 1805 the Morning Post newspaper (13th January 1805) had reported that: A very elegant Ball and Supper were given on Thursday night by Mrs Drummond, of Charing-Cross. In the interior decoration of the very tastefully fitted up residence nothing was wanting to render the entertainment attractive in every respect. A suite of rooms, three in number, were appropriated for dancing, cards, &c. Each apartment was illuminated by Grecian lamps, and bell lights. Precisely at eight o'clock the dancing commenced with Flora McDonald, a new dance, first introduced a few evenings since at a ball given in Cleveland-square by Lady Mary Drummond; it is a very lively and spirited tune. The ball was opened by the young Duke of Dorset and the beautiful Miss Drummond. The Earl of Aboyne danced with the Hon. Miss Arden, and Mr Drummond with Lady Kinnoul. Two sets were formed in the second dance, I'll mak ye fain to follow me. A very sumptuous banquet the company, mustering about 150 persons, partook of about midnight. The dancing afterwards re-commenced, and was kept up until five o'clock in the morning. Reels were danced; they were given with the trueHighland flingby Mr Stewart of Greenock; Mr Drummond, of Inverness; and another Gentleman, whose name we could not learn.

The ball was opened by the

Lady Campbell's BallThe Morning Post newspaper for the 26th of June 1809 reported on a Ball held by a Lady Campbell. She was Lady Elizabeth Campbell, wife of Major General Dugald Campbell of Auchinbreck (1742-1809), a serving officer out in India. The General had remained in India at the date of the ball along with their sons (he would die just a few months later in 1809). Their daughter, also named Elizabeth Campbell, had married Thomas Eyton (1777-1855) in December 1808, this ball may have been held in celebration of their wedding. The Morning Post reported (with dance references highlighted in bold):  Figure 4. Devonshire Place and Wimpole Street, 1799. Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Figure 4. Devonshire Place and Wimpole Street, 1799. Image courtesy of The British Museum.

On Friday evening, in Wimpole-street, a splendid ball and supper were given by the above Lady. It was attended by almost all the rank and fashion in the metropolis. The preparations corresponded to the well known taste of the accomplished hostess. The house was lighted up with chandeliers and lustres. About eleven o'clock, the dancing commenced with The Self, led off by Sir William E???? and Miss Macleod. Next followed[a list of 7 couples]At the hour of two in the morning the company partook of a sumptuous entertainment; at three the dancing was resumed with Sir Roger de Coverly called for by Mrs Malcolm, the spirited sister of Lady Campbell. Scotch Medleys, Reels and Strathspeys, out of number, succeeded; they occupiedthe light fantastic toeuntil half-past eight o'clock. So late an assembly has not been known since the days of the late Mrs Walker, of Masquerade celebrity.

This particular ball was hosted at Lady Campbell's home in Wimpole Street, a general view of the street can be seen in Figure 4. The ball was reported to have ended at half-past eight in the morning, a time so late that it had

Our ball of 1809 included a dance that we've written about before named Sir Roger de Coverly. This was a veteran dance that had seen a renewal of interest in the early 19th century, several variants of the dance were published at around this date. It was often danced at the end of an event, it's curious that we find it danced at this ball part way through the night. We've also investigated the concept of

Lady Saltoun's Ball Figure 5. The Crescent, Portland Place 1822, image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 5. The Crescent, Portland Place 1822, image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 1st of July 1809 carried a report of a Ball held by Lady Saltoun. Lady Saltoun (d.1851) was the surviving wife of Alexander Fraser the 16th Lord Saltoun of Abernethy (1758-1793). The ball may have been held to introduce Eleanora, their oldest daughter, to society. The Morning Post recorded (with dance references highlighted in bold): On Thursday last, in Portland-place, Lady Saltoun gave an elegant Ball and Supper. The company exceeded 200 fashionables of distinction. In the interior decoration there was nothing peculiarly[a list of 7 couples.]nouvelle. Grecian lamps and chrystal lights were used. The dancing commenced at half past eleven o'clock with The Self, led off by Lord James Murray and the Hon. Miss Frazer. Next followed:- We've studied some of the dances from this ball before. Fight about the Fireside was a popular tune dating back to (at least) 1767, we've also written of Reels and Strathspeys and the German Waltz elsewhere, you might like to follow the links to read more. Lady Saltoun had hired the celebrated James Gunter (1731-1819) to cater for the event, Gunter was a pioneer in the production of ices and ice creams.

Master of Ceremonies Ball, RamsgateThe final event we'll study in this paper is a little different, it was a Ball held by Mr Le Bas the Master of Ceremonies at the resort town of Ramsgate. On this rare occasion we have two different reports covering the event. The Kentish Gazette for the 29th of September 1809 recorded (with dance references highlighted in bold):  Figure 6. Ramsgate, seen from the West Pier, c.1825. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 6. Ramsgate, seen from the West Pier, c.1825. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Morning Post, also on the 29th of September 1809, reported (with dance references highlighted in bold):The Master of Ceremonies Ball, on Tuesday night, at Ramsgate, was a bumper, and more brilliant than any which the visitors of the Isle of Thanet have honoured him for many seasons past. Mr Le Bas's annual ball was given last evening. It far excelled the preceding one last year in brilliancy. The Assembly-room was fitted up with appropriate and tasteful embellishments; the band of music was well chosen and select; and the other arrangements, such as were calculated to afford the most perfect and satisfactory accommodation. The company began to arrive at half-past nine o'clock; at ten dancing commenced with minuets. The Duchess of Manchester led off the first country dance, The Marquis Huntly, with Colonel Macniel. Next followed Lady John Campbell, Col . Lumley; Lady Virginia Murray, Capt James. So numerous were the company, that four sets danced. The second dance was a new Scotch Medley, called for by Lady J. Campbell; this being a composition of the celebrated Niel Gow, in praise of the House of Argyle, it was a great favourite. The fairy feet and exquisite symmetry of a great proportion of the female dancers, were calculated to kill the admiring gazer. The country dances succeeded by strathspeys, &c. The Duchess of Manchester, in winding the nimble mazes of the Highland reel, charmed every one by the lovliness of its fascinations. About half-past one the music ceased, and at two o'clock the assembly broke up. Minor differences clearly exist between the two texts. They're largely consistent but the variations are an important reminder that we can't consider (any) published ball records to be entirely error free.

The second text, that of the Morning Post, begins with a string of unimportant banalities that could have been recorded of any ball. It then continued with the unexpected information that the Ball commenced with the dancing of Minuets. Minuets were rarely danced at this date, we've written more on this topic elsewhere, their being danced at Ramsgate hints at a formality normally associated with dancing at Court. The report goes on to reference a composition by Both newspapers focus their attention on the Duchess of Manchester. One records that her retinue arrived after the first country dance had begun, the other hints that she may have missed the minuet dancing. In both cases the public interest is in the country dance that she led off and in her partner for that dance. She evidently led the dancing of Reels, Strathspeys and Medleys.

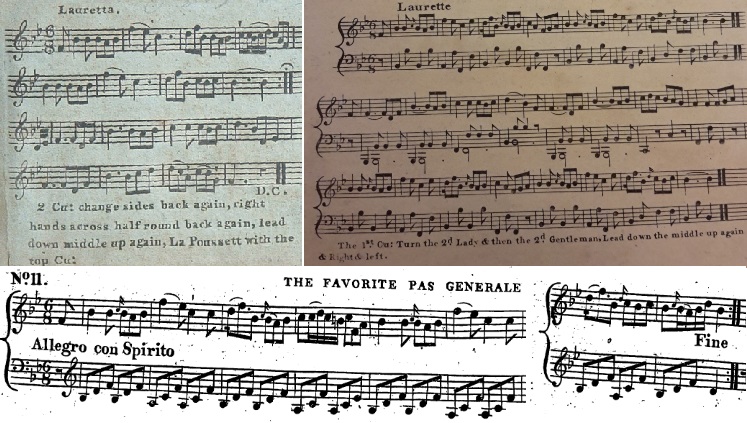

LauretteThe ball was opened by the Marchioness of Tavistock and Mr Whitbread, to the tune of Lauretta, and followed by at least fifty couple.(Duchess of Bedford's Ball) The first tune we'll investigate was named Lauretta, it is (probably) the tune more correctly known as Laurette. This identification isn't certain, arguments could be made to identify it as one of two different tunes, Laurette is the more probable of the two candidates. This more likely tune was adapted from an 1803 grand ballet by Henry Smart (1778-1823) that was also named Laurette, a copy of the score is available on the web courtesy of the Petrucci archive. The 11th movement in the ballet, a tune named as The Favorite Pas Generale (see Figure 7, bottom) was adapted into a Country Dance and published by several music shops in London between roughly 1804 and 1805. The Country Dance took the first eight bars from that movement and added an additional strain that seems not to be derived from the Ballet. Example publications of the tune include Dale's c.1804 4th Number (see Figure 7, top right), Davie's c.1806 13th Number, Walker's c.1805 10th Number and the Thompson collection of 24 Country Dances for the Year 1805 (see Figure 7, top left); the first two were published under the name Laurette, the Thompson publication issued it as Lauretta (matching the name used at our ball).  Figure 7. Lauretta from Thompson's Twenty Four Country Dances (for the Year 1805) (top left); Laurette from No 4. Dale's Collection of Reels and Dances c.1804 (top right); and the first 8 bars of The Favorite Pas Generale from Laurette, A New Favorite Ballet by H. Smart, 1803 (bottom).

Figure 7. Lauretta from Thompson's Twenty Four Country Dances (for the Year 1805) (top left); Laurette from No 4. Dale's Collection of Reels and Dances c.1804 (top right); and the first 8 bars of The Favorite Pas Generale from Laurette, A New Favorite Ballet by H. Smart, 1803 (bottom).

The other tune it could perhaps be identified with was a Country Dance derived from the 1801 ballet named Laura and Lenza by Charles Didelot (1767-1837). Several such tunes were in circulation; Archibald Duff, for example, would publish a tune derived from the ballet that he named Lauretta c.1812 in his Part First of A Choice Selection of Minuets, Favourite Airs, Hornpipes, Waltzs &c.. Duff's tune is unlikely to have existed (or at least to have been known) at the 1809 date of the Ball but other tunes derived from the same production could have been featured. It's perhaps notable that Thomas Wilson, in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore publication, provided a long list of dancing tunes that were popular at that date, he included both Laura and Lenza and Laurette within that list, thereby indicating that the names were associated with distinct tunes. It seems more likely that Henry Smart's Laurette ballet was commercially valuable. This was sufficiently true for a copyright action to be brought against the publishers of a Country Dance derived from the ballet in early 1806. The details of the dispute are only partially recorded, there are many details that aren't clear, what follows is the resolution of the dispute as recorded at the Court of Chancery in the British Press newspaper for the 13th of February 1806: Mr Agar, this day shewed cause against a motion of Mr Romilly, for dissolving an injunction of the Court, by which the Defendants (we could not, from the pleadings, collect their names) were restrained from selling a certain musical air. The Plaintiff had purchased of the composer, Mr Smart, the copy-right of the music of the ballet ofLaurette, and the Defendants, it was alleged, had infringed upon the right of publishing the same, which he had, for a valuable consideration, thus exclusively acquired, by selecting the most admired part of the music, and printing it, to the great prejudice of the sale of the ballet. The country dancing tune under dispute may have been the tune from our ball. The publication in question evidently included twelve country dances, that could have been Dale's 4th Number (see Figure 7, top right), any such identification is only circumstantial however. If it was the Dale publication then the defendants were being a little disingenuous; their version was indeed twenty-four bars long, but the final eight bars match the first eight, so the part that was copied was two-thirds of the tune, not one-third as reported; if one considers the bass line separately from the melody then a one-third argument can be made, but it's a little tenuous. All that can be said for certain is that a tune from the ballet was sufficiently popular that the copyright owner went to chancery to protect their rights; and they lost, as the tune in question was shown in turn to have been borrowed from another even older source! This dispute could have been the first case involving the copyright of a country dancing tune to be disputed in early 19th century London, we've written of several further disputes in another paper. The growing copyright uncertainty around country-dances in the mid 1810s may have hastened the demise of the entire country dance publishing industry, this dispute involving Laurette may have paved the way for that subsequent turmoil.

We're informed that at the Bedford ball some fifty couples followed the leading couple down the country dance. The dance was led off by the hostess's daughter-in-law, Anna Russell (1783-1857) (who would later become the next Duchess of Bedford ) and Mr Whitbread (possibly a relative of Samuel Whitbread (1764-1815) the Member of Parliament for Bedford). Fifty couples are an uncommonly large number of participants for a country dance, the hosts must have had a large room available to dance in. The tune was also featured at a Ball of 1807 (Morning Herald, 9th of May 1807) held by Mrs F. Pigou where it was reported: We've animated a suggested arrangement of Dale's c.1804 version (see Figure 7), of Davies' c.1805 version and the Thompson version for 1805 (see Figure 7).

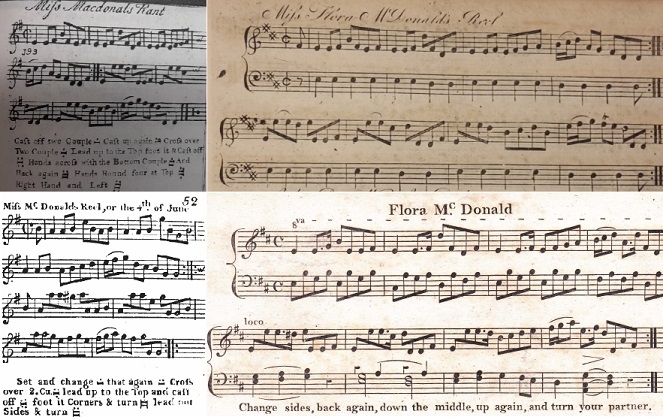

Miss Flora McDonald's ReelPrecisely at eight o'clock the dancing commenced with Flora McDonald, a new dance, first introduced a few evenings since at a ball given in Cleveland-square by Lady Mary Drummond; it is a very lively and spirited tune.(Hon. Mrs Drummond's Ball) We're informed by our correspondent that the dance named Flora McDonald was new in 1809 having been first introduced just a few days earlier. It may indeed have been new to the London fashionables that year and it would go on to be widely published in London throughout the years 1809 and 1810, the tune was much older however. It had been published at least as far back as the 1750s and the title referenced an event of the year 1746. It must have been popular over several decades, there may have been dancers present at the Ball who were well aware of the tune's antiquity.  Figure 8. Miss Macdonald's Rant from Rutherford's c.1756 Compleat Collection of 200 of the most admired Country Dances (top left); Miss Flora McDonald's Reel from Bremner's c.1758 third part of A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top right); Miss McDonalds Reel, or the 4th of June from the c.1781 2nd volume of Longman & Broderip's Compleat Collection of 200 favorite Country Dances, Cotillons and Allemands (bottom left); and Flora McDonald from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 9th Number (bottom right).

Figure 8. Miss Macdonald's Rant from Rutherford's c.1756 Compleat Collection of 200 of the most admired Country Dances (top left); Miss Flora McDonald's Reel from Bremner's c.1758 third part of A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top right); Miss McDonalds Reel, or the 4th of June from the c.1781 2nd volume of Longman & Broderip's Compleat Collection of 200 favorite Country Dances, Cotillons and Allemands (bottom left); and Flora McDonald from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 9th Number (bottom right).

The earliest publications of the tune that I can find were both issued in London in the 1750s; John Walsh published it in one of his volumes of Caledonian Country Dances (I've failed to track down which) under the name The 4th of June and Rutherford issued it in the c.1756 first volume of his Compleat Collection of 200 of the most admired Country Dances under the name Miss Macdonalds Rant (see Figure 8, top left). It would be issued in Edinburgh shortly thereafter in the c.1758 third part of Robert Bremner's A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances under the name Miss Flora McDonald's Reel (see Figure 8, top right). It was this third title that would go on to be most closely associated with the tune. The historical Flora Macdonald (1722-1790) to whom the titles allude is readily identified. She famously assisted the fleeing Bonny Prince Charlie (1720-1788) after his defeat at the April 1746 Battle of Culloden, the prince was said to have dressed as her maid as they travelled together. The alternative title of The 4th of June probably refers to the 4th of June 1746 when the fourteen Jacobite Colours (military banners) that had been captured at Culloden were ceremoniously burnt at Edinburgh's Mercat Cross by the city hangman. The 4th of June was also the Birthday of the monarch, King George III; the date of the flag burning may have been selected for that reason. The title of the tune held clear Jacobite (arguably anti-Jacobite) allusions. The Caledonian Mercury newspaper for the 5th of June 1746 wrote of the previous day's bonfire: Yesterday, at Noon, fourteen Stand of Rebel Colours displayed, and supported by John Dalgleish the Hangman, as chief Bearer, and thirteen Chimney-sweepers his Assistants, were carried down in Procession from the Castle to the Cross, (escorted by a Detachment of Col. Lees's Regiment) where a Bonfire was prepared, and amidst a numerous Crowd of Spectators were burnt by the Hands of the Hangman, with Sound of Trumpet and loud Huzzas from the Populace, after reading the Orders for that Effect, in presence of the Honourable Sheriffs of Edinburgh, who attended the Ceremony, with the Heralds in their Robes, and the Constables with their Battons. The tune would go on to be published on several further occasions in both London and Edinburgh prior to its rediscovery in 1809. It was printed in Edinburgh in the c.1761 second part of Neil Stewart's A Collection of the Newest and Best Reels under the name Miss McDonald's Reel; then in London in both the Bride collection of 24 Country Dances for 1769 and in the c.1781 2nd volume of Longman & Broderip's Compleat Collection of 200 favorite Country Dances, Cotillons and Allemands (under the compound title of Miss McDonalds Reel, or the 4th of June, see Figure 8, bottom left); then once again in Edinburgh in Alexander McGlashan's 1786 A Collection of Reels (as Miss Macdonald's Reel) and in Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances (as Miss Flora McDonald's Reel). Then, in 1809, it would appear amongst the collections of almost all of London's principal music sellers; examples include (in no particular order): Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 9th Number (see Figure 8, bottom right), Walker's c.1809 21st Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number, James Platts's 1809 12th Number, Dale's c.1809 15th Number, Ball's c.1809 1st Number, Goulding's c.1809 16th Number, Davie's c.1810 21st Number, Monzani's c.1810 12th Number, William Campbell's c.1810 25th Book, and the Fentum, Wheatstone, Preston and Bland & Weller collections of 24 Country Dances for 1810. It would also be referenced in Thomas Wilson's Treasures of Terpsichore for 1810. The tune was evidently popular in 1809, Lady Mary Drummond must have been thrilled to have been credited as being responsible. In addition to our Drummond Ball it would also be featured as the second dance at Mrs Leigh's Ball and Supper (Morning Post, 24th May 1809); I expect, given the publishing frequency of the tune, that it was a great favourite for the season. We've animated suggested arrangements of Button & Whitaker's c.1809 version, Campbell's c.1810 version, Platts's 1809 version and Skillern & Challoner's 1809 version (see Figure 8, bottom right). For futher references to the tune, see also: Miss Flora McDonald's Reel at The Traditional Tune Archive.

I'll make you be fain to follow meTwo sets were formed in the second dance, I'll mak ye fain to follow me.(Hon. Mrs Drummond's Ball)

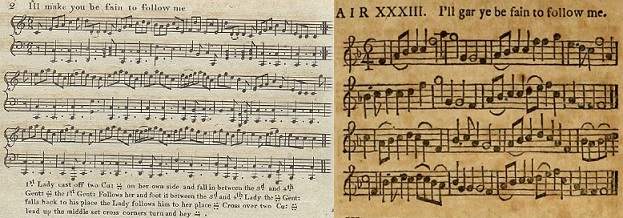

This tune is readily identified as being a popular air that was known (especially in Scotland) throughout the 18th century. The first publication of the tune that I can identify was printed as a song in London within the 1731 The Highland Fair or Union of the Clans by Mr Mitchell under the title Air XXXIII. I'll gar ye be fain to follow me (see Figure 9, right). The Traditional Tune Archive offers some earlier sightings of the tune in manuscript sources, it's better known today as the title for a c.1790 song by Robert Burns. The first arrangement of the tune as a dance that I can find was issued in London in the 1744 second volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances under the name  Figure 9. I'll make you be fain to follow me from William Campbell's 1798 13th Book (left) and I'll gar ye be fain to follow me from the 1731 The Highland Fair or Union of the Clans (right). Left image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Figure 9. I'll make you be fain to follow me from William Campbell's 1798 13th Book (left) and I'll gar ye be fain to follow me from the 1731 The Highland Fair or Union of the Clans (right). Left image courtesy of the National Library of Scotland.

Publication of the tune then moved to Edinburgh with the c.1758 third part of Robert Bremner's A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances as I'll make you be fain to follow me (the name that went on to stick with the tune). This arrangement of the tune differed slightly from that of the earlier publications but once again it was clearly the same tune. It would also appear in the c.1761 second part of Niel Stewart's A Collection of the Newest and Best Reels or Country Dances, as a song within David Herd's 1776 Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, etc. and in Robert Mackintosh's c.1796 A 3d Book of Sixty Eight New Reels and Strathspeys Also above forty old Famous Reels. Thereafter Niel Gow included it in his 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances and the Newcastle based Abraham Mackintosh published it in his c.1805 A Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Jigs &c.. The London publishers rediscovered the tune around the end of the 18th century, it would reappear in London's dance collections throughout the following decade. Publications included William Campbell's 1798 13th Book (see Figure 9, left) and the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1799. It would also appear in Bland & Weller's 24 Country Dances for 1800, Davie's c.1802 5th Number, Goulding's c.1803 3rd Number, Cahusac's 12 Country Dances for 1803, Dale's c.1804 3rd Number, Andrew's c.1805 9th Number, Walker's c.1806 11th Number, William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and in Broderip & Wilkinson's 1806 A Selection of the most Admired Dances, Reels, Waltz's, Strathspeys & Cotillons. It would also be referenced by name in Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and in Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ballroom.

The tune was also danced at fashionable balls throughout the first decade of the 19th century. Examples include the Countess of Leicester's 1800 Ball (Caledonian Mercury, 27th March 1800), Mrs Thellusson's 1801 Ball (Morning Post, 18th June 1801), Lady Cathcart's 1802 Ball where it was led off by Lady Murray (Morning Post, 12th March 1802) and Mrs Knox's 1802 Ball (Morning Post, 19th March 1802). The Queen hosted a Ball in 1803 which featured the tune (Lancaster Gazette, 28th May 1803). The King hosted a Fete at Frogmore in 1804 (in honour of the Duke of York's birthday) that once again featured the tune (Evening Mail, 20th August 1804), it reported that

The word

The most consequential publication of the tune (from the point of view of the London market) was that of William Campbell in 1798, Campbell was probably the first of the new wave of publishers to issue the tune (see Figure 9). Campbell included an unusual dancing figure in his version in which two dancers The tune had probably passed its peak of fashion by the date of our 1809 ball but it certainly remained known. We've animated suggested arrangements of Campbell's 1798 version (see Figure 9), of Preston's 1799 version and of Cahusac's 1803 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: I'll Mak' Ye be Fain to Follow Me at The Traditional Tune Archive.

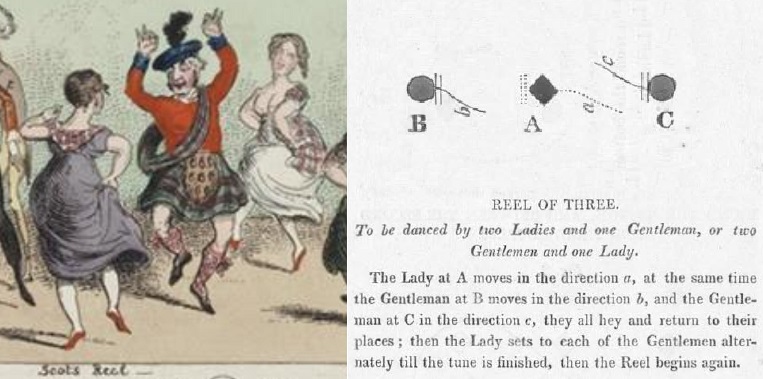

Reel of ThreeReels were danced; they were given with the true "Highland fling" by Mr Stewart of Greenock; Mr Drummond, of Inverness; and another Gentleman, whose name we could not learn.(Hon. Mrs Drummond's Ball) Scotch Medleys, Reels and Strathspeys, out of number, succeeded; they occupied "the light fantastic toe" until half-past eight o'clock(Lady Campbell's Ball) Reels, strathspeys, and German waltzes, concluded the night's amusement.(Lady Saltoun's Ball) Her Grace the Duchess of Manchester ... dances remarkably well, but excels in Scotch reels, which she introduced after the country dances, and in the rapid, various and short steps of which she certainly displayed the greatest agility and execution.(Master of Ceremonies Ball, Ramsgate)  Figure 10. A Reel of Three, detail from La belle assemblée, or, Sketches of characteristic dancing, 1817 (left). Thomas Wilson's Reel of Three from the 1811 3rd edition of Analysis of the Ball Room (right). Left image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

Figure 10. A Reel of Three, detail from La belle assemblée, or, Sketches of characteristic dancing, 1817 (left). Thomas Wilson's Reel of Three from the 1811 3rd edition of Analysis of the Ball Room (right). Left image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

The Reel was a Scottish form of dancing that was routinely danced in the ballrooms of London's nobility from the late 1790s. We've previously written of the Reel of Four and the general uncertainty regarding Scottish themed dancing in other papers, you might like to follow the links to read more. The first of our 1809 balls evidently included a Reel of Three that was performed by three gentlemen, we've not investigated this specific variant of the Reel before so will do so here (see also Figure 10).

The Reel dancing at our various events will have differed in the specifics but they're likely to have been danced with a degree of enthusiasm that would entertain the rest of the assembly. The Reel of Three was said to have been danced

The Reel of Three is likely to have been danced very much like a Reel of Four, it would include a mixture of The Reel, whether danced by groups of three, four, or perhaps even more dancers, was very much a part of the fashionable world of the early 19th century. A party of three or four dancers performing while everyone else watches (or at least kept out of the way) brings to mind the Minuet dancing traditions of the later 18th century... except that the Reel is a very different dance form! There are several excellent reconstructions of Regency era Reel dances available through Susan de Guardiola's website, you can find her interpretation of Wilson's New Reel of Three there.

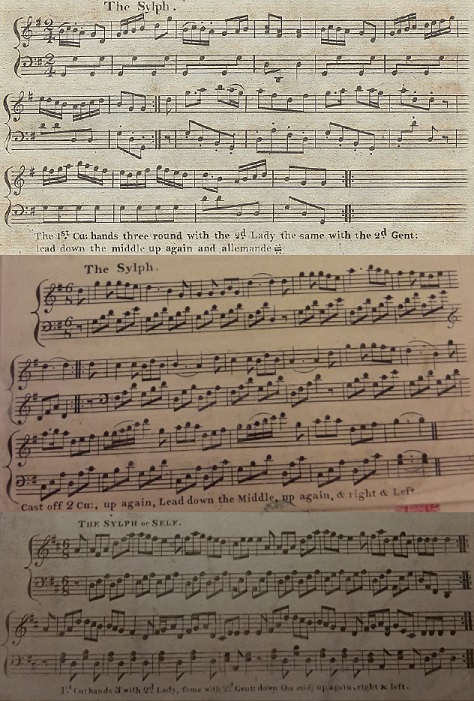

Figure 11. The Sylph from William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book (top); The Sylph from William Dale's c.1809 16th Number (middle); and The Sylph or Self from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number (bottom).

Figure 11. The Sylph from William Campbell's c.1808 23rd Book (top); The Sylph from William Dale's c.1809 16th Number (middle); and The Sylph or Self from Button & Whitaker's c.1809 13th Number (bottom).

The Self / The SylphAbout eleven o'clock, the dancing commenced with The Self(Lady Campbell's Ball) The dancing commenced at half past eleven o'clock with The Self, led off by Lord James Murray and the Hon. Miss Frazer.(Lady Saltoun's Ball)

One of the few tunes that is known to have been danced at more than one of our 1809 balls was the immensely popular The Self. This tune is a little tricky to investigate as there were three different but similarly named tunes all circulating in London at around the same date (see Figure 11). Two of the three tunes were issued under more than one title, it's likely that the publishers themselves were confused between them. Our tune was variously published as both

Our tune was the most popular of the three (as measured in both publication frequency and social references) but it was not the first of the three to appear. The first of the three tunes was probably the tune issued under the name The Sylph by William Campbell is his c.1808 23rd Book (see Figure 11, top). This tune was also published by the Goulding publishing house under the pluralised name of The Sylphs in both their c.1808 12th Number and their collection of 24 Country Dances for 1809. This first tune would then disappear for a year or so before reappearing under the name New Sylph in Wheatstone's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810 and in Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1811 6th Book. There's a degree of irony in what was probably the first of the three tunes being later republished as the The other two tunes appeared at approximately the same time, I can't with any certainty place a chronology on them. We'll first consider the other of the The Sylph tunes. This tune was only, as far as I can discern, published as The Sylph. It appeared in William Dale's c.1809 16th Number (see Figure 11, middle) and also in Davie's c.1809 22nd Number. The oddity with this tune was that the second strain of music consisted of 12 bars, the Davie publication identified four of them that would typically be omitted when danced. This tune would also appear in Andrews's c.1810 26th Number and in Bland & Weller's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810. Several of these publications would also include The Self, these two tunes would have been unambiguous and distinct to the purchasers of those publications. We've animated a suggested arrangement of William Dale's c.1809 version of this dance.

Our tune was the most frequently published of the three, once again it's impossible to place a precise chronology on those publications. Several publishers issued it unambiguously under the title The Self, examples include William Dale's c.1809 16th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1809 4th Book and in Davie's c.1810 23rd Number. Some issued it explicitly (and probably wrongly) as The Sylph including James Platts's c.1809 13th Number and Skillern & Challoner's c.1810 10th Number. The publishing house of Button & Whitaker even issued it under the compound title of The Sylph or Self in their c.1809 13th Number (see Figure 11, bottom), this was presumably in recognition of the ambiguity over the tune's intended name. The slightly later publications tended to use the title of The Self, examples include Goulding's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810, Bland & Weller's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810, Wheatstone's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810, Fentum's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1810 and in Logier's c. 1810 3rd Number. Thomas Wilson also referred to The Self by name in his Treasures of Terpsichore publications for 1810 and 1811. It's likely that The origins of our tune are unknown. Jonathan Blewitt published a rondo arrangement of the tune in 1809 (Morning Post, 18th July 1809) but it's unlikely that he was the original composer. Rondo arrangements were generally created from tunes that were already popular rather than the other way around. All three of our tunes seem to have experienced a sudden spark of interest, have remained popular for perhaps two to three years, then faded away again. I know of no social references to our tune being danced either before or after 1809. Edward Payne would go on to reference a tune named The Sylph in his 1814 New Companion to the Ballroom though which of the three tunes he was referring to is unclear. For futher references to the tune, see also: The Self [2] at The Traditional Tune Archive.

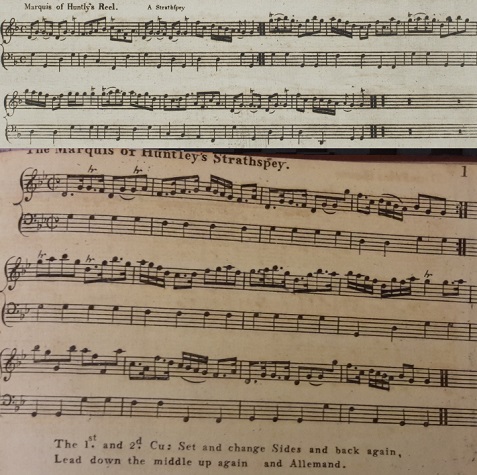

Marquis of Huntly's Reel / Marquis of Huntly's Strathspey Figure 12. Marquis of Huntly's Reel from William Marshall's 1781 A Collection of Strathspey Reels (above) and The Marquis of Huntley's Strathspey from Longman & Broderip's c.1793 Third Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c. (below).

Figure 12. Marquis of Huntly's Reel from William Marshall's 1781 A Collection of Strathspey Reels (above) and The Marquis of Huntley's Strathspey from Longman & Broderip's c.1793 Third Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c. (below).

Her Grace the Duchess of Manchester...led off to the merry tune of the Marquis of Huntley's reel. Her grace danced with Captain MacNeil, next to her, Lady Virginia Murray with Counsellor O'Dedy, Lady Campbell with Colonel Payne, &c. &c.(Master of Ceremonies Ball, Ramsgate)

This is another tune that is easy to identify but is mildly puzzling. The tune was composed by William Marshall (1748-1833) and published in Edinburgh in his 1781 A Collection of Strathspey Reels (see Figure 12). Marshall added The tune would be republished many times in Scotland over the next twenty or so years, either under the given name or as the Marquis of Huntly's Strathspey. It appeared in the c.1783 second volume of James Aird's A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs and in Alexander McGlashan's 1786 A Collection of Reels. These first few publications retained Marshall's name for the tune, later publications tended to prefer the alternate title of the Marquis of Huntly's Strathspey. Later examples include Joshua Campbell's c.1789 A Collection of New Reels & Highland Strathspeys, in John Anderson's c.1789 A Selection of the most Approved Highland Strathspeys and in Neil Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots slow Strathspeys and Dances. It would also appear in the 6th volume of McFadyen's A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs and in John Anderson's Budget of Strathspeys, Reels & Country Dances (they were issued at uncertain dates). Robert Mackintosh included it in his c.1803 A Fourth Book of New Strathspey Reels as did Archibald Duff in his 1812 A Choice Selection of Minuets, favourite Airs, Hornpipes, Waltzs &c.. The curiosity is that despite the tune's evident popularity in Scotland it seemed barely to have been published in London. The only London publication of the tune that I can confirm was that in Longmap & Broderip's c.1793 Third Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c. (see Figure 12). If there was any doubt over the popularity of the tune it might be dispelled by the fact that several London publishers attempted to provide the tune to their customers around 1809; Joseph Dale included a tune named The Marquis of Huntley's New Strathspey in his c.1808 12th Number, Monzani & Co. published a tune that they named The Marquis of Huntley's Strathspey in their c.1809 9th Number. These two tunes were not the Marshall tune. There can be little doubt that the Marshall tune was what was being danced socially however, the incredibly successful London based Gow band would surely have played the Marshall tune as they themselves had published it in Edinburgh. If any other Scottish themed tune was proving popular in London then they most likely would have published it in Edinburgh, they routinely did so for other such tunes. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Longman & Borderip's c.1793 version (see Figure 12). For futher references to the tune, see also: Marquis of Huntly's Strathspey (1) (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

Lady Charlotte Campbell's Strathspey & Lady Charlotte Campbell's ReelThe second dance was a new Scotch Medley, called for by Lady J. Campbell; this being a composition of the celebrated Niel Gow, in praise of the House of Argyle, it was a great favourite.(Master of Ceremonies Ball, Ramsgate)

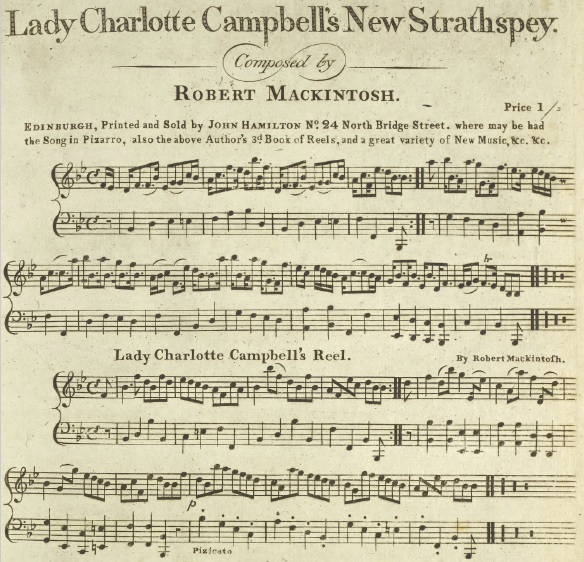

Identifying the tunes danced as a medley at the Ramsgate ball is a challenge. An initial anomaly immediately arises: the medley was described as being both  Figure 13. Lady Charlotte Campbell's New Strathspey and Reel from Robert Mackintosh's c.1800 publication of the same name.

Figure 13. Lady Charlotte Campbell's New Strathspey and Reel from Robert Mackintosh's c.1800 publication of the same name.

The next clues to note are that the tune was described as a

Yet another clue might be found in the dance having been called for by Lady John Campbell. Her identity isn't entirely obvious, she could have been Lord John Campbell's ex-wife Elizabeth Campbell (d.1818), they had been divorced in 1808 however (on the grounds of his adultery) so it seems unlikely that she would be referred to as Lady J. Campbell under such circumstances. The other strong candidate was the sister of both the 6th Duke and Lord John Campbell, she was Lady Charlotte Campbell (1775-1861). Charlotte had married Colonel John Campbell in 1796 (he had died earlier in 1809), as a widow she very well might have been described as Combining all of these clues together leads to one candidate medley that is more likely to have been danced at our ball than any other, the two tunes being Lady Charlotte Campbell's Strathspey & Reel. These two tunes weren't entirely new, they date back to around the year 1800, and they weren't by Niel Gow, they were instead composed by Robert Mackintosh (though Gow did publish both tunes in 1802). They were however dedicated to Lady Charlotte Campbell, presumably the same lady who called for the medley and a ranking member of the House of Argyll. This identification isn't certain of course but I've yet to find a more likely pair of candidates. They were also a somewhat successful pair of tunes in London at around our date.

The first known publication of our candidate tunes was in Edinburgh by Robert Mackintosh in a work named Lady Charlotte Campbell's New Strathspey (see Figure 13). The precise date of publication isn't known but it was likely to have been around the year 1800, it was certainly no earlier than 1796 as it advertised Mackintosh's 1796 3rd Book of Reels on the cover. Mackintosh described himself as the author of both tunes. Publication of the tunes would shortly follow in London; the Strathspey was included in Milhouse's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1801 (under the name Lady Charlotte Campbells Fancy) and also in Robert Mackintosh's c.1803 4th Book (Mackintosh and his band having been in London at around this date). The Gow family published both tunes back in Edinburgh in their 1802 Part Second of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Tunes, Strathspeys, Jigs and Dances. Meanwhile, and back in London, Joseph Dale issued both tunes in his c.1806 7th Number (and the Reel for a second time in his c.1809 15th Number). Goulding & Co. issued the Strathspey in London in their collection of 12 Country Dances for 1808, John Anderson issued both tunes in Edinburgh in his c.1810 Budget of Strathspeys, Reels & Country Dances. Both tunes were also referenced by name in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ballroom. An extraordinary reference to the medley also exists from 1805 where it featured at Mrs Du Pre's Masquerade (Morning Post, 20th May 1805), it was reported that: There was a degree of confusion surrounding the medley in London however, many other tunes with similar names were also in circulation at around the same date. Around a dozen other tunes variously named as Lady Charlotte Campbell's Strathspey, Lady Charlotte Campbell's Reel, or similar, were printed in either London or Edinburgh between the 1780s and 1820s. One such example was even composed by Nathaniel Gow. If a member of the public wanted to buy our medley they were liable to end up with sheet music for one of the other similarly named tunes! Ultimately the identity of the tunes danced at the Ramsgate Ball remains unknown. The medley we've identified as the best candidate wasn't new in 1809, it had even been danced for nearly 2 hours at a London Ball of 1805, but it may not have been widely known. It wasn't composed by Niel Gow but was by a celebrated Scottish musician and had been published by Gow a few years earlier. It was however dedicated to a senior member of the Argyll family and was probably called for at our ball by Lady Charlotte Campbell herself. If you can identify a better candidate medley then do please contact us as we'd love to know more! We've animated a suggested arrangements of Milhouse's 1801 version of the Strathspey, Goulding's 1808 version of the Strathpsey and of Dale's c.1809 version of the Reel. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Charlotte Campbell's Strathspey (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive and Lady Charlotte Campbell's Reel (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

ConclusionWe've investigated five balls from 1809 in this paper along with seven tunes or dances that were enjoyed at them. Many of the tunes and dances were of Scottish derivation though at least one was derived from the London stage. In several cases there is evidence that the London music sellers were themselves confused about the tunes, several issued alternative tunes under the same or similar names; this perhaps hints that the music buying public expected to be able to buy tunes they had only heard referenced by name (potentially in the same newspapers in which we find the surviving references in today). If you would like to recreate a ball of 1809 then the tunes and dances that we've encountered here would be very suitable to feature at your event. If you have anything further to share about these tunes and dances then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved