| Return to Index |

|

Paper 46 F. J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on DancingContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 22nd August 2020, Last Changed - 30th December 2021]The Norwich based dancing master Francis Joseph Lambert (1782-1849) published a fascinating little book on dancing in 1815 (see Figure 1); this paper contains a full transcript of Lambert's book, together with a brief commentary on his life and work. Lambert's treatise offers one of the most detailed descriptions of the use of Steps in English social dances of the early 19th Century, it is therefore of significant interest to anyone seeking to recreate the more elite style of dancing of the Regency period.  Figure 1. F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing

Figure 1. F.J. Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing

Index to the TreatiseLambert's Treatise on Dancing did not contain an index or table of contents; the following index is provided as an aid to locating pages of particular interest within the work, the names of the sub-sections have been invented for this purpose. They are not part of the original publication.

Francis Joseph Lambert (1782-1849)

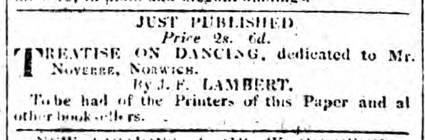

Aside from being the author of our Treatise, relatively little is known of Lambert. He was for many years the business parter of Francis Noverre (1773-1840) who was in turn the nephew of the celebrated Parisian ballet master Jean-Georges Noverre (1727-1810). Lambert dedicated his Treatise to his dear friend Francis; the content of the work was heavily influenced by the Noverrean style, the dedication went so far as as assure the reader that the text (which was addressed to Noverre) had  Figure 2. Lambert's advertisement for the book, from the Norfolk Chronicle the 9th December 1815. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

Figure 2. Lambert's advertisement for the book, from the Norfolk Chronicle the 9th December 1815. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

A brief biography of Lambert is available on-line courtesy of the Norfolk Record Office. The city of Norwich, at our date, was one of the largest cities in England; its walls had enclosed more territory in the middle-ages than those even of London, it was reputed to be England's second city; it was prosperous with a rich mercantile population. Norwich was the ideal location for a dancing master with impressive connections (and ambition) to teach genteel manners to the children of the wealthy. The academy of Francis Noverre and Francis Lambert was evidently successful, they remained in business together until c.1822 when Noverre entered into partnership with his own son. Lambert taught independently from this date. Lambert continued to advertise dance tuition into the 1840s, he eventually died in 1849.

Lambert advertised the publication his book in late 1815; a brief insert in the Norfolk Chronicle on the 9th December 1815 reads:

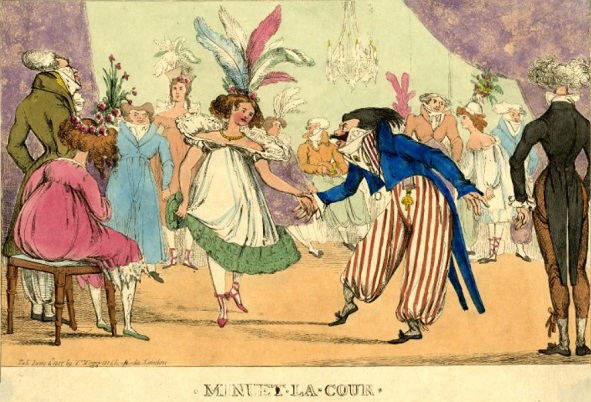

The Social Dance Industry of 1815Lambert's book was published in Norwich rather than London. The content of the book is quite different to those that were being published in London at around the same date; contemporary publications by such dancing masters such as Thomas Wilson, Edward Payne and John Cherry tended to focus on the perfection of the Country Dance, whereas Lambert's book detailed the correct use of Steps in French dances such as the Minuet.  Figure 3. The Devonshire Minuet, 1813. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. The Devonshire Minuet, 1813. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The London publishers rarely referred to Minuet dancing at this date, the Minuet had fallen from favour around the end of the 18th Century. Lambert explained (page 33) that

The Minuet was occasionally danced in the 1810s despite its reputation for being formal and old-fashioned, references to examples are scarce however. They were certainly danced at the formal balls at the Mansion House in Dublin, an example danced by Miss Wood and The Duke of Sussex was recorded in The Star newspaper for the 8th April 1817, such events seem to have been the exception. Formal minuet dancing required an entire room to politely watch as a single couple demonstrated their Minuet dancing prowess with well practised grace. Carefully orchestrated precedence rules governed who would dance and in what sequence, the Minuet balls of the late 18th Century might last for many hours with the guests presumably waiting in polite silence throughout. The Minuet's fall from prominence remained recent however, the general populace sometimes thought that it remained a favoured dance of the aristocracy. Thomas Wilson declared in the 1811 3rd edition of his Analysis of Country Dancing that

The public of the early 19th Century were increasingly aware of the use of

French Country Dancing in the form of Cotillions, Quadrilles and other dance variants were increasingly popular in 1815. The Quadrille would begin it's rise to ubiquity from 1816, the term

Lambert offered some observations with respect to the Country Dance:

Another curiosity involves Lambert's definition of the term Fancy Dance. This otherwise vague term is known from other sources, Lambert gave it a meaning (page 37) which is more generally useful: Lambert's Treatise is especially interesting in so far as it provides context for the use of steps in historical social dancing. They're most relevant to figure and fancy dances, less relevant to the typical social dances of the ball and assembly rooms. A polished dancer will have a repertoire of steps available to them but wont necessarily employ them while dancing; they will however be graceful in all of their movements, especially in polite company.

Text of Lambert's 1815 Treatise on Dancing

At the time of writing copies of Lambert's book are relatively hard to find; there are no copies available on the Internet and the copy that was once at the British Library has a status of What follows is a transcription of Lambert's book. It's reproduced as faithfully as I could achieve, with spelling, italics and punctuation as in the original. Page numbers have been emphasised, the text for the page is immediately below the page number (which thereby acts as a title), blank pages have been omitted. Where lines are split across more than one page an ellipsis has been added to both pages, this ellipsis is not in the original text. If a word is split across more than one line then it has been recombined in this transcription, potentially pulling the second part of a word onto the preceding page. An index to the treatise exists at the top of this document.  Figure 4. Francis Noverre (1773-1840), Lambert's business partner and the dedicatee of his book.

Figure 4. Francis Noverre (1773-1840), Lambert's business partner and the dedicatee of his book.

[page i]TreatiseOn Dancing. By F.J. Lambert Norwich Price 2s. 6d. Norwich: Printed and Sold by Bacon, Kinnebrook, And Co. [page iii]To Mr. Noverre, Norwich.Sir, In dedicating the following Treatise to you, I do but render tribute where it is justly due; since whatever merit may be attached to it, derives its source from yourself, who first impel'ed and facilitated the progress of my professional acquisitions, and with the consciousness that no one can justly tax with flattery a mere acknowledgement of benefits received, which benefits have been conferred in a manner that could not but deeply impress a mind possessing a common portion of generous or grateful sentiment. The pleasure of having an opportunity of publicly acknowledging my obligation ... [page iv]... to your much-esteemed friendship to me, is an object of first consideration in publishing this Treatise, as well knowing that whilst the merit it may contain is due to you, and deficiency must as justly be attributable to me alone. Your professional reputation is too firmly founded to suffer from, but may possibly be extended in some measure, by the circulation of some useful precepts, which have been honored with your approbation.

I am, Sir,

[page 1]IntroductionDancing is an amusement which all classes resort to upon occasions of festivity. It is considered a fine recreation, as it invigorates the body and contributes much to health: all countries have a particular attachment to this amusement; the most barbarous nations, even from any impulse of pleasure, express their joy by dancing. The origin of this art is not ascertained: we read instances of it in the writings of Moses; but like other arts, dancing was then rude and uncultivated, and as civilization increased so they were improved. In Greece likewise, which was at that time the most polished nation in the world, dancing was in great repute, though not ...[page 2]... so much esteemed among the Romans. The perfection which this art has risen to, has made it a fashionable accomplishment: a certain knowledge of it is requisite to almost all persons, as there are times when it is necessary to form one in the country dance, and a person never feels so aukward as upon this occasion, if he cannot conduct himself in a proper manner. The aukwardness of one person will throw a whole dance into confusion; and besides the annoyance to others, it shews a total ignorance of this polite accomplishment. The object of learning to dance is not to acquire the most difficult movements of the feet. The entrechat, pirouette, and other showy steps are only fit for the stage; to see a person capering like an opera dancer in the crowd of a country dance, would be ridiculous. We are not to imagine this style of dancing beautiful, because it is difficult: this is not the criterion of good dancing. The object to be attained is an ...[page 3]... easy carriage of the body, and a graceful management of the arms and head: all outré movements ought to be avoided - the dancing is elegant when it is natural, unaffected, and easy. *Monsieur Noverre has very justly observed,La Poésie, la Peinture et la Danse ne sont, ou ne doivent être qu-une copie fidèlle de la belle nature.Good dancing is not distinguished by the feet only, it is by the whole management of the body, the manner of presenting the hand, the using of the arms, &c. a person that dances well in this respect will be graceful in a room, and will be distinguished upon all occasions. The attainment of this must be of more importance than the practice of the most difficult movements of the feet. Judges of dancing are not dazzled by the execution of difficult steps - so much more is necessary to form a good dancer. When the attention is ... * Lettres sue la Dance par M. Noverre, ci-devant Maitre des Ballets, à Paris. [page 4]... wholly given to the feet, the most important and necessary part of it is disregarded, which is the management of the body. In slow dances, such as the minuet, the attention is given to the arms and head, and if they are gracefully managed, the dignity and elegance of it is more striking than the execution of the most difficult steps. The practise of dancing more calculated for the stage than an assembly-room, is fit only for a stage dancer; as the course of practice for this, is to turn out the hips, knees, and feet too much to look well in walking. Stage dancers may, in general, be known by this; the outward position of their knees and feet renders their appearance mechanical and inelegant; therefore this theatrical style ought to be avoided. The intention and use of the dancing room is to improve the manners and external appearance; the etiquette of it obliges a respectful behaviour; the courtesy and bow is observed on entering and quitting the room, and the frequent ...[page 5] Figure 5. The Dancing Lesson, Part 6, 1824. Image courtesy of the Yale University.

Figure 5. The Dancing Lesson, Part 6, 1824. Image courtesy of the Yale University.

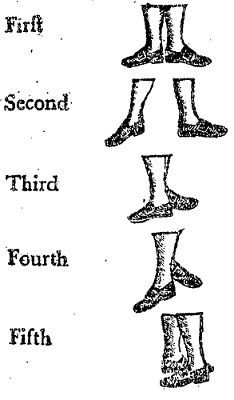

Dancing is not acquired to any great perfection without an early application to it. Children from five to eight years of age can move their limbs more nimbly, and with greater ease to themselves, than at any other time; and when they have acquired an active use of them, they always retain it, and as they gain strength they acquire an animated style and perfection which pupils do not who begin at a more advanced age; their limbs are strongly set, and ... [page 6]... consequently there is more difficulty in acquiring that active use of them; there is a certain stiffness in their dancing, which is not overcome without considerable application and pains. The progress which young children make at the age of five and six, appears slow, if nothing more is considered than merely learning a number of steps. It would be wrong to push them too forward at that age, especially if they are weakly, for it is putting them beyond their strength, and they acquire bad habits, which are not afterwards easily eradicated: those who are stronger will bear to be put more forward, with less danger, but it is not necessary; a good foundation is of much more importance, because as they gain strength, they will execute difficult movements with ease and in every respect well. By a moderate course of practice the limbs are strengthened, but too much exertion, at so tender an age, has the contrary effect, as it weakens and displaces the ankles and other joints, which are too ...[page 7]... much pressed upon. Children that are weakly and rickety ought to be begin dancing at an early age, as natural defects, as well as acquired ones, may be very much remedied by a proper attention and course of practice. There are few children that are exempt from some defect or other in their construction: one foot may turn in too much, the shoulders too high, or one of them higher then the other; defects of this kind may be attributed, in a great measure, perhaps to bad nursing, and are therefore acquired ones. If a child is allowed to stand too long without support, and encouraged to walk when it is but just able to stand, the joints and limbs, which are flexible and yielding in the infant state, get bent or wrung; and when a defect is perceived, it is considered a natural one, and no more means are used to remedy it. Defects are easily contracted at this age, and it once time confirms their position, it is too late to correct them. It is probably that most defects are acquired ones; and ...[page 8]... yet there are two which are so common that they seem to be natural. It is what the French call being either jarreté or arqué. A person is said to be jarreté, when the hips are straightened and inwards, the knees large and so close that they touch, and even join together, when the feet are distant one from the other. A person who is jarreté, forms nearly the figure of a triangle from the knees to the feet; there is a largeness and bulk in the interior of the ankles, and a considerable elevation of the instep. The contrary defect is observed in a person who is arqué; the hips are widened and the knees opened, so that from the hips to the feet, these parts describe a line which forms in some manner the figure of an arch. Persons so constructed have, besides long and flat feet, an exterior jutting-out ankle. Two defects so directly opposite prove at once that lessons which suit the one would be injurious to the other. The course of practice necessary for a person who is jarreté, is to observe a continual ...[page 9]... bending of the knees, keeping the hips as much outwards as possible; by this means the parts that are too close together, are removed. A person who is arqué requires to have the knees, which are too distant from each other, brought closer together. To dance or walk well it is necessary for the feet to turn outwards, but the natural form is the reverse: observe young children, and they walk with their feet quite straight, therefore the contrary position is purely invention. Defects are frequently contracted by a wrong method of practising to turn out the feet. In sitting the heels should be together, and the knees as well as the feet ought to turn outwards; if when the heels are together, the knees are kept close, with the feet turned out, the ankles are forced forward, and have a jutting-out appearance: where the shoulders are very forward, care should be taken, after dancing, or any warm exercise, to flatten them; the joints and muscles relax from warmth, and being loosened will more easily yield; ...[page 10]... as the body cools, the limbs become firmly set, and retain a good or bad position. We observe in the labouring classes, the shoulders very forward and round; this may be attributed more perhaps to their manner of holding themselves, than to their laborious employment. When warm, they throw themselves into a lounging easy posture until they have rested and cooled themselves; the muscles are relaxed and unstrung, as it were, and the joints readily yield: from habits of this kind they become round shouldered, and frequently deformed.It is not my intention, nor is it necessary to minutely describe all the various movements, steps, and dances, that are taught in schools; such a work would be rendered unintelligibly tedious to any pupil, and would defeat my intention, which is to benefit those who are learning or may have learned to dance. I have therefore merely selected certain familiar movements and ...  Figure 6. The five positions, from S.J. Gardiner's 1786 A Definition of Minuet-Dancing

Figure 6. The five positions, from S.J. Gardiner's 1786 A Definition of Minuet-Dancing

[page 11]... steps, which may be easily comprehended, and which are the foundation of dancing. The different dances which are taught must be soon forgotten after leaving school; they can only be retained by masters who are in the habit of shewing them; yet it is necessary that pupils should learn them, as the art cannot be attained but by such practice. I shall not attempt to burthen the memory with a description of what is more calculated to be shewn than described. My object is, to impress upon the mind, certain rules and observations, which if attentively considered and practised, will not fail to give a chaste and unaffected style, and an easy and graceful carriage.[page 13]TreatiseThere are five different positions of the feet, from which various movements and steps are made: The first position is formed by placing the heels together with the feet not more turned, than is necessary to keep the body steady.By placing the right foot to the side in a line with the left heel, keeping the knee straight and the toe pointed and just touching the ground so as to steady the body, which is wholly supported upon the left foot, the second position is formed. Bring back the right foot, placing the heel in the hollow of the left, in the centre, ... [page 14]... with the right foot well turned out, and the third position is formed.To form the fourth position, move the right foot forward from the third position, in a straight line, keeping the knees quite straight, with the toe pointed and merely resting upon the ground, the whole weight of the body being upon the left foot. Bring back the right foot, placing the heel to the left toe, observing to turn out the foot, keeping both knees straight, and the weight of the body upon both feet, and the fifth position is formed. The same is to be observed is making them with the left foot. In making movements the positions must be strictly attended to. Steps are composed of different movements, such as the Coupé, the Assemblé, the Glissade, the Jetté, and the Changement de jambe. There are other movements, which I shall have occasion ... [page 15]... to notice, but which have no particular name - they are common and familiar to all; such as the hop, walking upon the toes, &c. It will be seen that the above movements are each differently made.To make the Coupé, when the knees are bent slide the right foot forward flat upon the ground to the fourth position, from the first, third, or fifth position, wherever it may be, the Coupé may be made to the side or backward; if to the right, slide the right foot, keeping it flat, to the second position, finishing with the left heel raised; if it is made backward with the right foot, it must be brought to the first position, and whilst the knees are bent, slide it backward to the fourth position, finishing with the left heel raised. In making the Coupé, observe to keep the foot flat - the style is theatrical and effected when it is made with the heel raised. [page 16]The Assemblé is a spring from one foot upon both, place the right foot to the second position, balancing the body upon the left, and in springing from the ground, bring the right foot to the fifth or third position, falling upon both toes and flattening the feet immediately afterwards; to make the Assemblé backwards, the movement is made from the second position, throwing the right foot behind the left, to the fifth position instead of forward.There are several ways of making the Glissade; to make it to the right, place the right foot forward to the fifth position, when the knees are bent, slide very quickly, the right foot with the heel raised to the second position, by means of a gently spring from the left foot, bringing it at the same time behind the right, marking the fifth position; to make it to the left, begin with the left foot. The same movement may be made by changing the feet; place the left foot forward to the fifth ... [page 17]... position, slide the right foot from behind the left, to the second position, bringing the left to the fifth position forward; or if the right foot is at the fifth position before, in sliding it to the second, finish with the left foot forward - by that means the feet are changed. The Glissade should be particularly attended to; the style is very peculiar, and the movement itself so useful in dancing, that it cannot be too well known. It requires great expression; the movement should be firm, pointed, and well marked.The Jetté is made from the first, second, third or fifth position; it is by throwing the body from one foot upon the other. Place the right foot to the fifth position, and the knees being bent, make a gentle spring off the left foot, throwing the body forward with the right, to the fourth position; to continue the movement, the left foot is brought to the first position, and the spring is made from the right foot.  Figure 7. Madame Duval dancing a Minuet at the Hampstead Assembly, 1822. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 7. Madame Duval dancing a Minuet at the Hampstead Assembly, 1822. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

[page 18]To make the same movement backward, the foot is thrown to the fourth position behind, instead of forward.The Changement de jambe is merely changing the feet from the third or fifth position. Bend the knees, and in springing from the ground, change the feet from the third or fifth position behind, to the same position forward. In describing the above movements, it is seen how necessary it is to observe well the different positions, and as they are the foundation from which steps and movements proceed, they must be correctly made. Beginners do not perceive and are much embarrassed to distinguish the difference between movements and steps; in order therefore to render this more clear, I will arrange a few steps and confine myself to the movements which have been described. [page 19]Make a Jetté forward with the right foot, and an Assemblé with the left foot, forward to the fifth position; this is a step in two movements, composed of the Jetté and Assemblé; to repeat the same step, observe the same movements, beginning with the left foot.Make a Glissade to the right, from the fifth position, and an Assemblé with the right foot, finishing at the fifth position behind; this is another step in two movements, composed of the Glissade and Assemblé Make two Jettés forward, the first with the right foot, the second with the left, an Assemblé with the right foot to the left position, and a Changement de jambe; this is a step in four movements, composed of two Jettés, an Assemblé, and a Changement de jambe. Make an Assemblé with the right foot ... [page 20]... behind to the fifth position, a Changement de jambe, a Jetté forward with the left foot, and an Assemblé forward with the right foot; this is another step in four movements.Make three Glissades plain to the right, keeping the right foot forward at the fifth position, a Changement de jambe, three Glissades back again to the left, and an Assemblé with left foot behind to the fifth position; this is a step in four movements to the side and back again. In the foregoing pages I have given the foundation of dancing, at least that part of it which regards the mechanical movements of the feet. I have endeavoured to shew how steps are composed of different movements, so that the difference between then may be clearly distinguished. Those which I have described may be called French steps, as they are composed of such movements as are used in the French steps. [page 21]The French have given names to particular movements and steps, and in many cases the names of them express what they are and how they are made; the Glissade from glisser, to slide, the Jetté from jetter, to throw, the Changement de jambe, a change of the feet, &c.Scotch steps are in four or eight movements; the most useful of them is the step forward in four movements, which is used in forming the figure of the reel. The first movement is made by walking forwards with the right foot to the fourth position; the second movement by placing the left foot behind the right to the fifth position; the third is another walk with the right foot to the fourth position; and in the fourth movement the left foot is brought forward to the fourth position, at the same time making a hop upon the right foot; the left remains raised from the ground, ready to make the same step. [page 22]Irish steps are in three or six movements, and as they are very similar, I shall only describe one of them, which will be sufficient to give an idea of the nature of those steps.The step forward, or circle step, is in three movements; you walk forward with the right foot to the fourth position, in making the first movement, and immediately afterwards the left foot is brought forward to the fourth position and raised from the ground, the whole weight of the body being placed upon the right. In making the second movement you hop upon the right foot, at the same time bringing the left over the right instep. The third is made by repeating the last movement. Having given a description of the different kinds of quick steps, so that their particular style and composition may be distinguished, I shall now merely take notice of some few, which I shall have occasion ... [page 23] Figure 8. The Le Pas Grave minuet step, 1777. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 8. The Le Pas Grave minuet step, 1777. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

As the following steps may not be familiar to all, I will endeavour to describe them. These are the Sissonne, the Bouré, the Pas-grave, and minuet step forward. The three last are slow steps, used in the minuet: there are several ways of making the Sissonne. The single Sissonne is a step in two movements. The Sissonne à l'Anglaise (or double Sissonne) is in three movements; it is made forward, backward, to the side, and obliquely. To make the single Sissonne forward, the first movement is an Assemblé with the right foot to the fifth position, at the same time bending the knees, and as you straighten them again, life the left foot from behind, placing it at the second position, and making a hop upon the right foot, which ... [page 24]... in the second movement. To continue the step, make the Assemblé forward with the left foot, and the hop on the right. To make it backward, the Assemblé is made behind to the fifth position, instead of forward. To make this step to the side and obliquely, you do not change the foot, by making a step alternately with the right and left foot, but join as many steps as may be necessary together, with whichever foot you may begin with. In order to understand this more thoroughly, make a few single Sissonnes to the side. If the step is made to the left, the Assemblé is made with the right foot forward to the fifth position, observing to bend the knees as the foot falls to the ground; as you make the second movement, place the right foot to the second position and hop upon the left; it is seen by this, that the right foot is a proper situation to continue the step. To make it obliquely, observe the same movements, only make the step in an oblique direction.[page 25]The Sissonne à l'Anglaise (or double Sissonne) differs from the single in having three movements. After the Assemblé, which is the first movement, you hop twice instead of once. Observe that the two last movements are made exactly as quick again as the first, so that although there are three movements in it, it take no more time to make than the single step in two movements. In every other respect the double Sissonne is varied like the single.The Bouré is a step in three movements, and it may be made in any direction, like the Sissonne. It is always a step in three movements. The first is a Coupé, the other two are walking upon the toes. Observe, that the movements of it are regular and equal in point of time. To make two Bourés en avant (forward), begin with a Coupé with the right foot, and walk upon the toes two movements, finishing with the right foot flat upon the ground at the fourth position, and the ... [page 26]... left heel raised to the fourth position behind. Bring the left foot to the first position, and make the Coupé forward, with the accompanying two movements upon the toes. To make the Bouré en arriere (backwards), the Coupé is made from the first position to the fourth position behind, and the movements upon the toes, walking backwards to the same position.The Pas-grave is perhaps one of the most difficult steps which is used in the minuet, by reason of its particular slowness; but if it is well danced it adds much to the dignity of the minuet. It cannot be danced by any but very forward pupils. It may be attempted, and the mechanical movements may be executed, but it would only tend to point out the defects of the dancer, as it requires that firmness and elegance of manner which cannot be expected in young pupils. There is besides the Pas-grave forward, the single and double; but as these steps are difficult and ... [page 27]... ill calculated to be understood from description, I shall confine myself to a description of the Pas-grave forward only, which step I shall have occasion to mention by way of example hereafter. There are four movements in it; the first of which occupies the first bar of the music. You begin the step from the fifth position; to make the first movement bend the knees, and afterwards in straightening the left knee again, raise the right heel, keeping the knee bent and the toes upon the ground; this is the first movement. In the second, the right foot is raised from the ground and placed at the fourth position. The third and fourth movements are made by rising upon the right foot, and bringing the left forward to the fourth position.The minuet step forward consists of a Coupé and a Bouré forward, and in a division of the time in making it. Although there are but four movements, this step ... [page 28] Figure 9. A View of the Ball at St James's on her Majesty's Birth Night, 1782. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

Figure 9. A View of the Ball at St James's on her Majesty's Birth Night, 1782. Courtesy of the Royal Collection Trust.

What I have already described relates to the management of the feet only, which is the least part of dancing. I will in the following pages give rules for the management of the arms and head, which is not ... [page 29]... only the most necessary and important part of the art, but the most difficult to be attained. The observations that are made to pupils respecting this are only thought of by them when in the dancing-room, and even then so indifferently, that they scarcely understand what is said to them; the reason is, they think it of no consequence, and that the execution of steps is alone worthy of their attention and practice. It requires study and particular attention to be able to manage the arms gracefully in dancing; and as the importance of it is not seen, the study of it becomes dry and uninteresting, and consequently it is but too much neglected. The management of the body upwards is of more consequence in dancing than the most practical knowledge of the use of the feet. A person cannot be said to dance well unless he excels in this particular. In order to acquire it, great attention should be given to the minuet and to the courtesy or bow. I will endeavour to describe ....[page 30]... the positions and movements of the arms by some observations upon the minuet.Those who are not acquainted with this dance would not understand it by description only, and to others it is not necessary. I shall merely therefore introduce it as exemplary to the use of arms. After the bows and courtesies at the beginning of the minuet, you prepare in the first movement of the Pas-grave or minuet step forward, to give the hand, and in the second movement it is presented; the gentleman always taking the lady by the hand. It is understood that the first movement of the minuet step is very slow; the movements of the feet govern those of the arms, and consequently the movement of the arms is equally slow and regular. In the first movement of the Pas-grave, as you bend the knees let the arm gently fall, inclining the hands inwards, by bending or rounding the elbow; during this movement, as you straighten the left knee again, ... [page 31]... raise the elbows, inclining the hand still nearer the body, and as you make the second movement of the Pas-grave, present the hand to your partner. In making the steps to give the right hand after the figure of the minuet, observe the same movement of the arm, in the Pas-grave, but in the three following movements of this step the arm remains still. In the first movement of the minuet step which immediately follows the Pas-grave, continue to raise the arm gradually, keeping the elbow as high as the hand, and inclining the hand rather inwards, so as to give a roundness to the arm. The thumb should rest upon the fore finger, keeping the other fingers loose, the body upright, and the shoulders well drawn back, with the head turned to the right, in order to see the person who is dancing with you. As you approach your partner, raise the hand and give it, and in quitting raise the arm and bring it round to the side upon a line with the body, keeping the elbow a little round and the ...[page 32]... hand inclining downwards; here let the arm fall by degrees until you reach the corner where the left hand is given. Throughout the minuet keep the arms round and the hands rather inwards; in giving both hands, the arms remain still during the Ballancé; but in the first movement of the Pas-grave or minuet step forward, both arms fall as you bend the knees, and in the second movement begin raising them, observing the same direction as for the right hand. As you approach your partner in the step forward, continue to raise both the arms, keeping the head turned to the right and the left arm more raised than the right in opposition to the head. In the bow and courtesies at the end of the minuet, keep the arms round and the elbows away from the sides.The rules which I have here given for the use of the arms are not confined to the minuet alone; if they were, the recollection ... [page 33] Figure 10. The Minuet La Cour, 1817. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 10. The Minuet La Cour, 1817. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

I will next give some general rules for the arms and head. It has already been observed, that the most difficult part of dancing to be attained is to be able to manage the body upwards. This consists in the opposition of the head, arms and feet. Whenever the right or left arm is raised, or the head is turned to the right or left, there is a reason for it, but if this is not understood by pupils, they raise indifferently the right or left arm, and as they do not see themselves when dancing, ... [page 34]... they are not aware of the effect of it; but those before whom they are dancing are immediately struck with the aukward appearance of a person when dancing, if the proper arm is not raised. That pupils may not be subject to such errors, let them attentively consider and make themselves acquainted with the following rules:The arm is placed in opposition to the head and foot. If you are making a side step with the right foot upon a straight line, the left arm should be raised, the right arm placed to the side, and the head turned well upon the right shoulder. Here the left arm is placed in opposition to the head and to the right foot. If the same step is afterwards made back again with the left foot, the right arm must be raised, the left placed to the side, and the head turned to the left. Here the same opposition of the arm, head and foot exists. The body should incline a little towards the foot that you are dancing with; this ... [page 35]... gives strength and animation to the step, besides you lose the balance of the body, if it is not perpendicular when one foot is raised from the ground. If a step is made upon an oblique line to the right or left, and there is reason to raise both arms, the arm which is raised the highest depends upon the foot which the step is made with. In order to see this more clearly, make four double Sissones with the right foot obliquely to the left, raise the left arm in opposition to the right foot, turn the head to the right in opposition to the left arm, and raise the right arm, only observing to keep it lower than the left. Here the left arm is placed in opposition to the head and the right foot; the position of the arms is the same as in the minuet in giving both hands. Finish by making a Changement de jambe, and as you change the foot so change the arm and the position of the head. There are many steps which do not shew so pointedly the effect of the opposition of the arms and head. The ...[page 36]... Glissade does not, because in making this step the feet are scarcely raised from the ground, and both feet are moving nearly at the same time; therefore in steps of this description, the arms are only raised, in those dances which are composed of several; they are then used to form the different figures. It appears from the above rules that the foot governs the arms, and the arms the head, as the head is placed in opposition to the arm; and yet there is an exception to this rule in the minuet. When the right hand is given the head is turned to the right in order to see the person who is dancing, but in this instance the position of the arm is peculiarly adapted to that dance; for although the arm is raised, the hand is no higher than the elbow, so that it does not prevent you from seeing your partner, to whom the attention should invariably be directed. If the hand was raised higher than the elbow, which it is upon all other occasions, it would have an aukward appearance; ...[page 37]... the person dancing would seem to look at his own hand, instead of the person with whom he is dancing. These observations upon the management of the arms cannot be too much impressed upon the minds of pupils; they may from the knowledge of them practice the use of the arms with as much facility as the feet. The figures of Cotillons and fancy dances are formed by the arms, and if they are not well managed, the effect which the figure ought to have is lost, and the aukwardness of a pupil, not a good dancer in this respect, would be very conspicuous.A fancy dance in four, five, six or any other number, is composed to a certain piece of music; the steps are well adapted to the style of it, there is the same connection and subject, and if the dance is well composed, it appears so interwoven with the music, that a step or figure could not be taken away, without spoiling the dance. If there is a pause in ... [page 38] Figure 11. The

Figure 11. The Hands Acrossfigure, a detail from the 1819 An Election Ball. The figure is not being performed following Lambert's advice. Image courtesy of the British Museum. In the country dance the attention should be given more to the management of the arms than to the feet, because the ear will naturally adapt easy movements suitable to the tune; the only attention that is necessary with respect to the feet is, to have them well turned out and pointed, that they may not incommode those who are dancing, and to move them exactly in time to the music. It is not the feet that are looked at, it is the whole carriage; persons are distinguished by this for their genteel and elegant style. The hands across, which is a singular figure in itself, shews the management of the arms and head to great advantage. When you present the right hand, turn the head ... [page 39]... and look at the person to whom the hand is given, and observe the opposition of the arm to the head; the left arm is raised much higher than the right, and in giving the left hand raise the right in opposition to it. The effect of this is striking, but if the hand is carelessly given, without looking at the person, and the contrary arm hanging down, the figure has no expression or effect, and the dancing is inelegant.I cannot close these observations without earnestly recommending to pupils to consider the intention and use of the dancing-room. The object of learning steps and dances is perhaps the least part of it. It is to improve the carriage and give a confidence in entering and quitting a room; and to attain this the courtesy and bow are constantly attended to; the practice of them deserves more serious attention than any other part of the dancing lesson. Pupils are well aware of the ... [page 40]... attention which masters give to this; and as they are distinguished marks of good breeding through life, surely the practice of them is of the first importance.

ConclusionLambert's text is a fascinating insight into an aspect of Regency era dancing that most authors were reluctant to write about. It not only offers an insight into the movements and steps that might be taught to children in the dancing-room, it also offers a direct insight into the tuition of the great Noverre dynasty of dancing masters. If you enjoy recreating the dances of the Regency era then an important and apparently contradictive issue arises: Lambert considered a repertoire of Steps to be an important accomplishment for the polished dancer, but acknowledged that they were not especially important to the most popular social dance form of the day. If you enjoy Regency era Country Dancing (whether in longways sets or in squares) then the Steps to be used when dancing weren't predetermined, individual dancers would do whatever came naturally with no attempt to synchronise those steps across an entire ballroom. The more important consideration was the general carriage of the body itself, especially that of the head and arms, and how one interacted with the other dancers. Lambert recommended a baroque style of movement for all social dances, the arms and head should be moved in opposition to the movement of the legs and feet. We've investigated the subject of embellishment in Regency era social dance in more detail elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. Lambert's style was not universal of course, dancers two hundred years ago didn't dance in a single consistent and proscribed fashion. Moreover, most dancers would not acquire the degree of perfection recommended by Lambert and the other elite dancing masters. If you want to recreate Regency era social dances following Lambert's advice then a focus on the graceful use of the arms and head will be of more importance than a precise and perfected use of the feet, if you prefer to recreate the dances in a different way then that's fine too - Lambert wasn't the appointed spokesman for his generation! We'll leave this investigation there; if you know more then do please Contact Us, we'd love to hear from you. |

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved