| Return to Index |

|

Paper 44 Grand Duke Nicholas at Brighton Pavilion, 1817Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 20th May 2020, Last Changed - 11th February 2025] Figure 1. Grand Duke Nicholas depicted during his visit to Britain in 1817. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 1. Grand Duke Nicholas depicted during his visit to Britain in 1817. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Late 1816 saw a visit to Britain of Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia (1796-1855, see Figure 1), the second in line to the Russian throne. Nicholas would, later in life, go on to become Tsar Nicholas I, his visit to Britain was an opportunity to learn of another European super-power from personal experience. Britain was the home of the Industrial Revolution, steam power fuelled mechanical processes that led to cheaper goods of a higher quality. Mechanisation affected trade on a global scale and it fuelled an Empire; Britain was proverbially the

It's easy, with the disadvantages of hindsight, to miss just how dramatic the societal changes had been in Britain; the Russian state was sensible to take notice. One satirist, commenting on the pace of change, joked (Cumberland Pacquet, 2nd June 1823): The tunes and dances that were reported to have been danced at the ball are:

The Visit of Grand Duke NicholasNicholas was the third of the four sons of Tsar Paul I (1754-1801), Paul in turn was the son of Catherine the Great (1729-1796). Nicholas' older brother Alexander (1777-1825) became Emperor of Russia in 1801 after their father's assassination; it was Alexander who was in power during Napoleon's aborted invasion of Russia in 1812 in which Moscow burnt and Napoleon's Grande Armée was all but destroyed by the cruel Russian winter. Alexander led the counter invasion of France in 1813 and 1814, he personally oversaw victory at the 1814 Battle of Paris. Peace was declared in 1814 and the Congress of Vienna was instigated in an attempt to negotiate a lasting settlement. Tsar Alexander I visited London in person in June 1814, he was greeted by cheering crowds but could only stay for a couple of weeks, he may however have been impressed with what he saw. Some months later Napoleon returned from exile for his Hundred Days of restoration, this triggered an abrupt end to the Congress and led to the 1815 Battle of Waterloo. After that things would be different; Europe had suffered enough of warfare, it was time to rebuild. Nicholas, as the third of the four brothers, was not expected to rule Russia. Alexander's daughters had died when young so it was the second of the four brothers, Grand Duke Konstantin (1779-1831), who was expected to succeed Alexander; Konstantin surprised everyone by renouncing his claim to the throne in 1823 making Nicholas the immediate heir. That was yet to happen in 1817 of course. Nicholas was nonetheless of political significance, he was betrothed to the 15 year old Princess Charlotte of Prussia (1798-1860) in 1814, a marriage that would strengthen the alliance between Russia and Prussia; the wedding would take place in July 1817, Nicholas would first be sent on educational tours of both Russia (May to September 1816) and Britain (November 1816 to March 1817) in preparation.  Figure 2. Silk Mills at Derby, 1809. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2. Silk Mills at Derby, 1809. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The Courier newspaper for the 21st November 1816 reported:

He would then undertake a rapid tour of England and Scotland, the Morning Chronicle wrote that The remainder of the Grand Duke's stay involved yet more travelling and numerous splendid entertainments in London; he left Britain in early March 1817, he was to return to Russia and his own Royal Wedding.

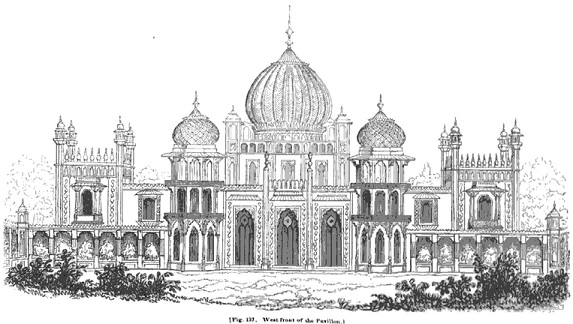

Figure 3. Design for the West Front of the Pavilion from Repton's Red Book, originally 1808.

Figure 3. Design for the West Front of the Pavilion from Repton's Red Book, originally 1808.

The Royal Pavilion at Brighton

George, Prince of Wales (1762-1830) (later King George IV), first visited the seaside town of Brighton in 1783; it was reported of the 21 year old heir to the throne that

The Prince would secretly and illegally marry Mrs Fitzherbert (1756-1837) in late 1785, Brighton had been and remained a suitable place for the couple to spend time together. Rumours of a more substantial building project circulated in 1787; the Caledonian Mercury for the 5th April 1787 dismissed the reports: The Pavilion remained a favourite destination throughout the Prince's life; it was repeatedly enlarged and redeveloped over many years, most famously by the architect John Nash from 1815 onwards; at the date of our 1817 ball it was in a transitional state and was still being developed, it would nonetheless have looked much as it does today - an imperial palace in an Indian style on the south coast of England. The pavilion at Brighton was a favoured place for the Prince Regent to get away from the official obligations and responsibilities of court and family; he could do as he pleased at Brighton.

Princess Charlotte's Birthday Ball, Jan 8th 1817

The Prince hosted numerous parties at Brighton, including a ball at the Pavilion on the 8th January 1817; this event was in celebration of his daughter Princess Charlotte's 21st Birthday and would act as preparation for the Grand Duke's visit the following week. The Oxford Herald (11th January 1817) reported that  Figure 4. The West or Garden Front of The Pavilion at Brighton, 1824.

Figure 4. The West or Garden Front of The Pavilion at Brighton, 1824.

The 1818 Memoirs of Her Late Royal Highness Charlotte Augusta, Princess of Wales, &c. recorded the following of the birthday ball at Brighton: The invitation tickets expressed[around 28 couples]Out of Mourning;the Court sables, consequently, were laid aside. The dresses of the Ladies were peculiarly elegant, many of them splendid; diamonds, rubies, and pearls, being in sparkling profusion. The Court was officially mourning the death of Frederick I, King of Württemberg (1754-1816) at the start of 1817, he was the Prince Regent's Brother-in-law and was husband to yet another Princess Charlotte (1766-1828), the mourning would continue until the following day, the 9th of January (The Courier, 12th November 1816). The courtiers should have been wearing their mourning sables but the Prince ordered that the guests at the birthday ball should not do so; we've written about dancing during court mourning before, you might like to follow the link to read more. This dispensation would not be required the following week for the Grand Duke's Ball, the period of mourning had ended by then. We're informed that the quadrilles at the birthday ball were led by Mrs Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte (1785-1879), she was an American socialite who had married Napoleon's brother Jerome (1784-1860) back in 1803. Their marriage was not a diplomatic success and the couple were divorced under American law in 1815, it had previously been annulled under French law some years earlier; this had resulted in an unfortunate situation in which Jerome had remarried under French law in 1807 and yet Elizabeth remained married to a bigamist under American law until 1815. Elizabeth's replacement (Jerome's new wife) was a daughter of the same Frederick I of Württemberg for whom the court were supposed to be in mourning! Elizabeth's situation had been complicated and perhaps not entirely dissimilar to that of Mrs Fitzherbert, it's possible that the Regent felt compassion for her situation. It hardly seems credible that official mourning was not only suppressed for the ball, but that the diplomatically embarrassing ex-wife of the deceased's son-in-law was also given a position of honour at the event! Other dancers that evening included the Austrian ambassador Prince Esterhazy (1786-1866) and the serving Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh (1769-1822).

The preparations were complete, all was ready for the arrival of the Grand Duke and his entourage the following week.

The Grand Duke's Arrival at Brighton, Jan 15th 1817

Grand Duke Nicholas arrived in Brighton on Wednesday the 15th January 1817, together with a large group of other dignitaries. The Morning Post for the 17th January 1817 reported (in a column with the title  Figure 5. Party in the Pavilion's Music Room, from The Royal Pavilion at Brighton by John Nash, 1826. This room was yet to be constructed in 1817.

Figure 5. Party in the Pavilion's Music Room, from The Royal Pavilion at Brighton by John Nash, 1826. This room was yet to be constructed in 1817.

The Grand Duke Nicholas, and other illustrious personages being expected at the Pavilion yesterday, the 10th Royal Hussars and the 51st Infantry, all Waterloo heroes, were drawn up, forming an avenue between them for carriages to pass, extending from the North gate of the Pavilion, with the colours, bands, drums, trumpets, and fifes of the regiments. The weather was damp, but the concourse of spectators was very great. A few minutes before five o'clock his Imperial Highness and suite passed through the military avenue, the colours waving, and the bands playingGod save the King, while the acclamations of the populace gave additional interest to the scene.

A report in the Public Ledger for 17th January 1817 added in reference to the 15th:

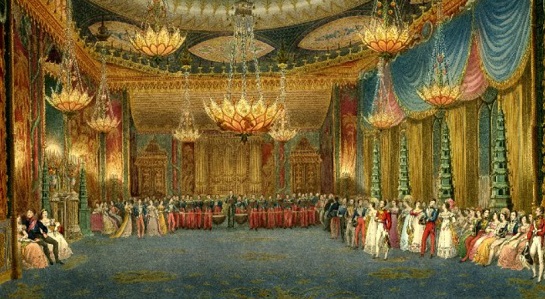

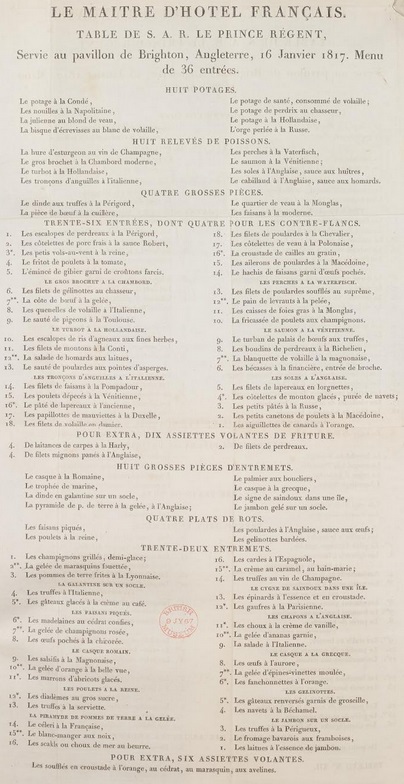

The Grand Ball at Brighton, Jan 16th 1817The Prince hosted his dinner and ball in the Grand Duke's honour on Thursday the 16th January 1817. Forty five guests were invited to the meal, they included the Royal Dukes, the Grand Duke and his entourage, and the major foreign ambassadors. The Prince had previously hired a celebrated French chef to his personal staff, Marie-Antoine Carême (1784-1833), it was Carême who was tasked with preparing the 100+ delicacies that would be served at the banquet. The menu for the event survives within Carême's 1842 Le Maître d'hôtel français (see Figure 6) - it's a wonder that any of the guests were able to dance after such a meal!

The grand ball was held that same evening, the 45 guests from the meal were joined by a large selection of dignitaries and socialites, some were locals but many had travelled for the event. The reports of the ball in the press varied in their detail; for example, The Times newspaper for the 20th January 1817 summarised the proceedings as follows:  Figure 6. Carême's menu for the banquet from his 1842 Le Maître d'hôtel français

Figure 6. Carême's menu for the banquet from his 1842 Le Maître d'hôtel français

The Morning Chronicle for the 20th January 1817 offered a more interesting account of the ball including details of the dancing (which have been emphasised): In compliment to his Imperial Highness, Duke Nicholas, the Prince Regent gave a splendid entertainment at the Pavilion, of a dinner and ball. Some small differences do exist in the accounts of the dancing between the sources. Here's how The Courier described the event (18th January 1817): Towards nine o'clock the company began to assemble for the ball, and in less than an hour almost every individual expected had arrived. The Master of the Ceremonies for the evening was Sir Edmund Nagle (1757-1830), it would be his job to facilitate the dancing; he would go on to be appointed the Groom of the Bedchamber when the Prince Regent became King George IV in 1820. We're told that a group of army officers performed at least some of the quadrilles; presumably the officers had been drilled in the choreographies ahead of the ball, they would be dancing for the enjoyment of the guests with a (presumably) impeccably synchronised performance. The Morning Post newspaper for the 18th January 1817 shared further details again. They listed many of the guests at the ball, and added: Thetout ensemblewas indescribably splendid - the dresses of the ladies were brilliant; a more costly display of ornamental embellishments has been rarely witnessed. Many of the nation's local newspapers carried reports of the Ball too, generally sourced from the London papers. We're told that most of the guests from the Birthday Ball the previous week returned for this grand ball, and that once again British manufactured clothing was to be worn.

After a long night of dancing the company must have been exhausted. The following day (Friday the 17th) was spent idling in Brighton; The Courier (18th January 1817) reported:

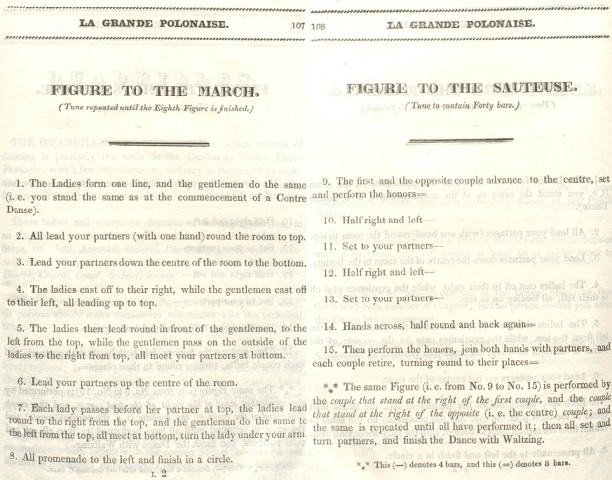

The Prince RegentThe ball was opened before eleven o'clock by the Duke of Clarence and Lady Charlotte Cholmondeley. About thirty couple, with suitable vivacity, followed. Tune, The Prince Regent.(Morning Chronicle) The Duke of Clarence and Lady Charlotte Cholmondeley led off to the admired and lively tune of the Prince Regent.(Courier) Towards ten o'clock the Ball was opened by the Duke of Clarence and Lady Charlotte Cholmondeley, who led off to the inspiring air called The Prince Regent, and about 35 couple followed.(Birthday ball) The accounts of both balls state that this was the initial dance of the evening and that the same pair of dancers led off at both events. We're told that around 35 couples followed for the birthday ball and around 30 for the Grand Duke's ball; this would take quite a long time to dance through and would be tiring for the lead dancers. One of those dancers was the Duke of Clarence, he is better known to history as King William IV, he took the throne when his older brother died in 1830. All of the accounts confirm that it was a lively tune. Several tunes were published under the name The Prince Regent, it's uncertain which was danced at our balls; we've written about the tune in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.  Figure 7. La Grande Polonaise from G.M.S. Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master

Figure 7. La Grande Polonaise from G.M.S. Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master

Polonaise & WaltzThe next was a waltz;...The fifth was a waltz, called and commenced by the Grand Duke. His Imperial Highness, as adopted in Russia, preceded the waltz by a Polonaise march and step, in which the dancers move round the space alloted for the exercise in graceful motion, ere the more intricate varieties of the waltz are pursued....the Grand Duke led off a Polonaise with Miss Seymour(Morning Chronicle) The Grand Duke and the Countess of Lieven joined among the waltzers, and they were much admired for their elegance and grace.(Courier) There was evidently a good deal of waltzing at the ball as indeed there had also been at the birthday ball the week before. Nicholas himself indulged in the waltzing, he danced with the Russian ambassador's wife, Countess Lieven, amongst others. We've written about the couple-waltz in previous papers, the dance had been growing in popularity in Britain since the start of the 19th century, but it was increasingly socially acceptable from perhaps mid 1814 (when Nicholas' brother Alexander famously waltzed in London).

The unusual detail for our ball was that Nicholas followed a Russian convention and preceded the waltz with a

The dancing master G.M.S. Chivers published a brief guide to

Cotillions & Quadrilles... the third, a cotillion ...(Morning Chronicle) waltzes and quadrilles were introduced for about one hour....Several quadrilles were performed by some of the Officers of the 51st Regiment of Light Infantry that were much admired.(Morning Chronicle)

The terms  Figure 8. Waltzing at the Pavilion c.1820. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 8. Waltzing at the Pavilion c.1820. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon TownThen the Duke of Clarence called the second dance of I'll gang nae mair to yon town, which he led off with Mrs Wigram.(Courier) The second dance was called by the Royal Duke I'll gang nae mair to yon town who led off with the same accomplished partner.(Birthday ball) The sequence of the tunes differs slightly across the reports, but this tune was acknowledged to be the favourite of the Prince Regent, it was often called at his balls so it's no surprise that it would be danced at our ball. It featured at both the Birthday ball and the Grand Duke's ball; it had also featured at the Carlton House Ball of 1811 and countless other balls since; it was arguably the most popular dancing tune of the entire Regency period. We've investigated the tune in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. The dance was led off by the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV) and Mrs Selina Wigram (d.1866); Mrs Wigram was married to Robert Wigram (1773-1843), her father (d.1809) had been appointed physician-extraordinary to the Prince back in 1791, he was reported to have regularly attended the Prince for the Brighton season. Selina was presumably known to the royal household; her husband was knighted in 1818, he would inherit his own father's baronetcy in 1830.

The Fairy DanceThe Fairy Dance was next called, and led off by the Duke of Clarence with Miss Seymour.(Courier) The Fairy Dance is another tune that we've studied previously, you can follow the link to read more. We're told that once again the dance was led off by the Duke of Clarence.

Waterloothe fourth a country dance, called Waterloo, which was led off by the Grand Duke and Lady Charlotte Cholmondeley, followed by the Duke of Clarence and the elegant Mrs Wigram.(Morning Chronicle)

There were several tunes in circulation named Waterloo, we've investigated them before in a previous paper.

The TankThe Royal Duke again danced, having called for The Tank.(Courier) Yet again The Tank is a tune we've studied in a previous paper, and once again the dance was led off by the Duke of Clarence. The tune was published in London from around 1809 and was probably composed by Lady Ashbrook.

The White CockadeCountry dances again commenced; the White Cockade ...(Morning Chronicle) The White Cockade was an old tune that had returned to significance in 1814 as the symbol of the resurgent Bourbonist party in France, it was worn by people who chose to publicly distance themselves from the Napoleonist party. We've written about the tune in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

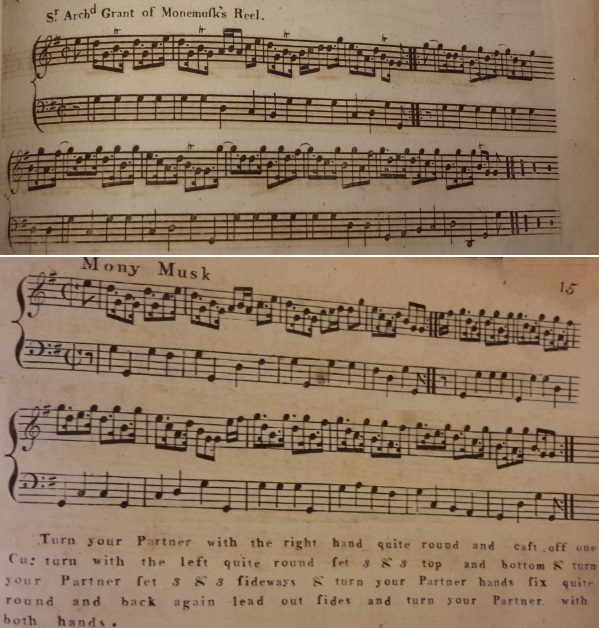

Mony Musk... Money Musk ...(Morning Chronicle) This popular tune is one we've not written about before so shall explore in a little more detail here. The tune was composed by Daniel Dow (1732-1783) and was first issued in Edinburgh under the name Sr Archd Grant of Monemusk's Reel within Dow's c.1778 Thirty Seven new Reells & Strathspeys (see Figure 10). The precise date of Dow's publication is uncertain; there's little doubt that he was the genuine composer (though earlier tunes with a similar melody are known), the date of the composition and publication is variously given as between 1775 and 1780.  Figure 10. Sir Archd Grant of Monemusk's Reel from Daniel Dow's c.1778 Thirty Seven new Reells & Strathspeys (above), and Mony Musk from Francis Werner's Book XVIII for the Year 1785. Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.a.(3.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 10. Sir Archd Grant of Monemusk's Reel from Daniel Dow's c.1778 Thirty Seven new Reells & Strathspeys (above), and Mony Musk from Francis Werner's Book XVIII for the Year 1785. Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.a.(3.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Aside: Dating Dow's collection is challenging. The date is of some interest as his book is thought to thought to have been the first to feature the wordStrathspeyin its title. Dow's earlier work, Twenty Minuets and Sixteen Reels or Country Dances, is known to have been published in 1773 (e.g. as referenced in the Caledonian Mercury, 27th February 1773). The later work can date no earlier than that.

Our tune was first dedicated to Sir Archibald Grant of Monymusk, Aberdeen; identifying Grant is complicated as several generations of Grants shared the same name. He could have been Sir Archibald Grant (1696-1778, 2nd Baronet), or Sir Archibald Grant (1731-1796, 3rd Baronet), or even Sir Archibald Grant (1760-1820, 4th Baronet). Given Dow's preference for youthful fashionables, the youngest Grant seems to have been the most likely dedicatee, he would have been 18 at our estimated publication date of 1778 and would just have received the right to the title

The next known publication of the tune was in London where it was included within Francis Werner's Book XVIII for the Year 1785 under the simplified title of The tune was widely published but it seems not to have been widely danced at society balls; it may of course have been very popular, the name of the tune was certainly known, but it tends not to appear in the few programmes that survive. It was named as being danced at an 1809 ball hosted by the Princess of Wales at Kensington Palace (Morning Post, 29th May 1809), and then at our ball of 1817 in Brighton. It seems to have retained relevance over more than 30 years from first publication in London through to at least our Ball of 1817. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Francis Werner's version from 1785 (see Figure 10) and of one of Thomas Wilson's arrangements from 1809. One curiosity of the various Mony Musk publications is that the minority which include dancing figures tend to feature the same arrangement, the Wilson and Werner figures will (for example) be found to be very similar, despite Wilson's having modernised them according to his own system. For futher references to the tune, see also: Money Musk (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Sir Roger de Coverley... Sir Roger de Coverley ...(Morning Chronicle) Dancing was kept up with great spirit till five o'clock, when the Ball terminated in the true old English style, with the deservedly popular dance of Sir Roger de Coverley, led off by the Duke of Clarence and Miss L Caton.(Birthday ball)

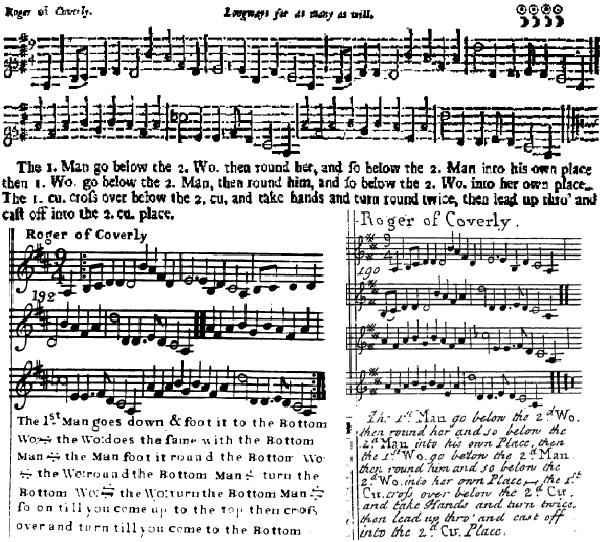

Sir Roger de Coverley was a popular choreographed off-formula country dance in which everybody interacts with everyone else; and as with the Polonaise dance above, the musicians were required to pay attention to the dancing in order to play sufficient repetitions of the tune. Country Dances at this date were almost universally arranged as  Figure 11. Roger of Coverly from Playford's 1695 The Dancing Master, 9th Edition (top); from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2 (left); from Johnson's c.1740 A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (right).

Figure 11. Roger of Coverly from Playford's 1695 The Dancing Master, 9th Edition (top); from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2 (left); from Johnson's c.1740 A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (right).

The origins of the dance are unclear; the tune and title may perhaps be ancient (I have no opinion regarding that debate) but they first appear arranged in a country dance arrangement in the 1695 9th edition of Playford's The Dancing Master under the name Roger of Coverly (see Figure 11, top). The tune, when first published, was arranged in 8 bars of 9/4 rhythm music; the associated dancing figures were those of a fairly standard country dance. There was nothing, at this date, to hint at the success the tune would go on to enjoy in the 19th century.

A new daily publication named The Spectator was launched in 1711, it would have a significant effect. The Spectator wasn't a newspaper as such though it did seek to educate its London readership with philosophical and humorous stories. The eponymous but unnamed The Spectator was sufficiently popular for the main characters to take on a life of their own, the name Sir Roger de Coverly would turn up in print throughout the 18th century as a result; the collected editions of The Spectator were regularly reprinted and widely enjoyed across the 18th century and into the 19th. Our tune appeared in print several times across the 18th century, one example can be found in the first volume of Johnson's c.1740 A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (see Figure 11, right); the Johnson version was identical with that of Playford, both the tune and dancing figures remained the same. A further example can be found in Walsh's c.1718 Compleat Country Dancing Master. A more interesting version can be found published in Charles and Samuel Thompson's c.1764 second volume of their Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (see Figure 11, left); the Thompson edition reprinted the Playford music but it also featured the initial variant of the now iconic dancing figures. It's unclear whether these figures predated the Thompson publication or whether the Thompsons (and their choreographer) introduced the figure themselves; they clearly decided to print a different figure than had previously been in circulation. The Thompsons were aware that the music had been published several times before, but many of their customers might have thought it a new tune named for the infamous character in The Spectator.

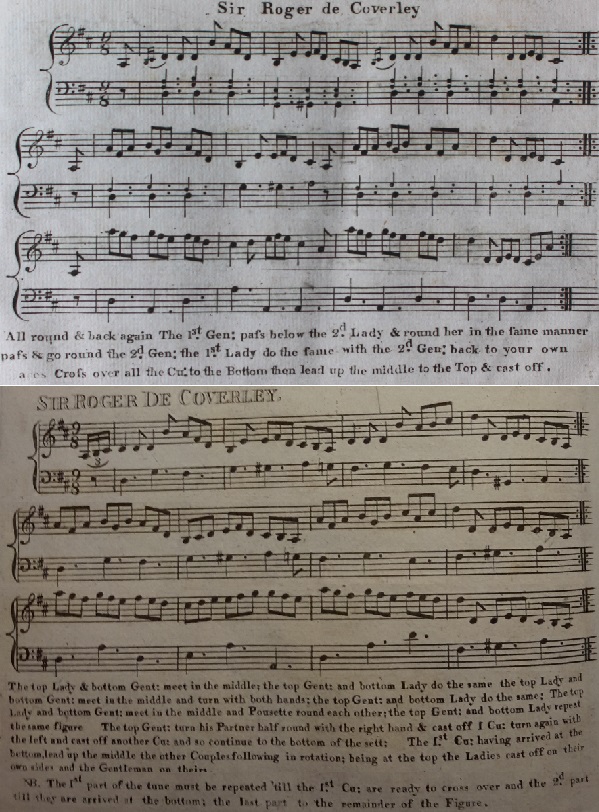

The late 18th and early 19th centuries saw a large increase in the number of music publishers operating in London, several of them reprinted Sir Roger in the early 19th century. The dance was in the process of becoming newly popular as a mixer for use at the end of an evening of dancing. Thomas Wilson in his 1820 Complete System of English Country Dancing wrote of Sir Roger de Coverley that The first of the new generation of 19th century publishers to print the dance was probably William Campbell in his c.1803 18th Book (see Figure 12, top). Campbell normalised the music into a 9/8 time signature (rather than Playford's 9/4 arrangement) and added a third strain of music and a bass line. Campbell's dancing figures were somewhat similar to those of the Thompson publication, though not exactly the same; Campbell's arrangement offers an intermediate version between the Thompson version and the subsequent arrangements that would become better known.  Figure 12. Sir Roger de Coverley from William Campbell's c.1803 c.1803 18th Book (top), and from James Platts's c.1811 25th Number (bottom). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 12. Sir Roger de Coverley from William Campbell's c.1803 c.1803 18th Book (top), and from James Platts's c.1811 25th Number (bottom). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(10.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Approximately concurrent with the Campbell publication was another issued by Joseph Dale in his c.1804 3rd Number. I suspect that Campbell published before Dale but the precise sequence is uncertain and unimportant. Dale's version is of interest as it's essentially a reprint of the c.1764 Thompson arrangement; Dale modernised some of the wording (he used Thomas Wilson in his 1808 Analysis of Country Dancing then offered a new figure for the dance that merged elements of both the Thompson/Dale and Campbell versions, together with new innovations perhaps of his own invention. Wilson also offered some simple country dancing figures for use with the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore, in so doing he identified the tune has having three parts thereby indicating his preference for the Campbell music. He went on to publish the figures with an accompanying score in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room, his music was a minor variation on that printed by Campbell. Yet another variant of the dance was published by James Platts in his c.1811 25th Number (see Figure 12, bottom); Platts published the Campbell music (in 3 parts and arranged with a 9/8 time signature), with a variation on Wilson's dancing figures. The general structure of the dance across these various publishers is in either two or three parts (depending on whether there are two or three phrases to the music). The three sections are approximately as follows:

The dance then iterates with a new leading couple (the original second couple), and continues to repeat until the original leading couple return back to the top.

The Platts publication adds an interesting detail regarding the music:

It's unclear which variant of the dance would have been enjoyed at our ball in 1817, what is clear is that several different variants were known and enjoyed. Further variants would go on to be published later in the 19th century; for example, Chappell published figures in 1838 whereby the second section was replaced with a chain figure, and the third with the leading couple making a static arch for the rest of the company to cast down and through. Many later arrangements feature a For futher references to the tune, see also: Sir Roger de Coverley at The Traditional Tune Archive

La Boulanger... and the Boulanger were called and led off by the Duke of Clarence.(Morning Chronicle) The final dance named as having been used at our ball was La Boulanger, it was another choreographed mixer dance that was similar in nature to Sir Roger de Coverley. The couples would form up in a circle (rather than a longways set) and everyone would dance with everyone else; the musicians had to pay attention to the dancers and repeat the strains as many times as necessary for the movements to complete. The dancing figures associated with La Boulanger were more consistent across publishers than those of Sir Roger though at least two different tunes were published for use with the dance. We've studied La Boulanger in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Conclusion

Our 1817 ball was conducted in a less formal style than the typical London balls we've studied of the preceding two decades. Brighton Pavilion was the Prince's We've studied several historical balls in our recent papers, this one has been the most modern. It's modern in the literal sense (the balls we've studied to-date were held between 1799 and 1816) but also in the sense that it's the most likely to have been recognised by modern regency-dance enthusiasts. Many of the conventions will be familiar to modern ball-going reenactors and enthusiasts:- a variety of different dance styles, some choreographed dances, several mixer dances, use of both modern and ancient (yet fashionable) tunes, newly arrived dance styles that might never have been experienced before, and so forth. The most significant characteristic may have been the prevalence of mixer dances, dances in which everyone interacts with each other; such dances minimised the stuffy precedence rules that might be experienced at court balls, the dancers were inherently each-other's peers; the power-politics of typical country-dances involved couples having to wait for the leading couple to draw them into the dance, the mixer dances towards the end of the evening minimised that formality. Several of the dances may have required the musicians to pay attention to the dancing and to adapt the music in-situ; this is a technique largely lost in the modern era of recorded music, it seems to have been fundamental to how dancing worked back in 1817. A dance like the Waltz required the leader of the orchestra to change the tempo of the music as it was being danced, skill was required to gauge the temperament of the room and to gradually nudge the dancers appropriately.

It's unclear whether the Prince's balls at Brighton had always enjoyed this less-formal arrangement. The style may (or may not) have been new but it was certainly becoming popular; entertainments of a similar nature were increasingly being held around the nation. The old Country Dances were going out of style; free-form Waltzes and choreographed Quadrilles were taking over the ball rooms of the aristocracy, dances in which the performers received an approximately equal share of the entertainment. The dancing masters in London were actively inventing new styles of dancing, some would be adopted by provincial dancing masters around the country. The immediate future of ballroom entertainment would focus on the It's unclear the extent to which Grand Duke Nicholas's visit to Britain influenced his future policy; he left England in March 1817 and travelled home to Russia and his own royal wedding. He became Tsar Nicholas I in 1825 and he ruled in Russia until 1855; perhaps he retained fond memories of his British tour and the time he spent at Brighton as an honoured guest of the Prince Regent. We'll leave this investigation there, if you have any further information to share do please Contact Us, we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2025

All Rights Reserved