English Regency Dances, Costumes, Balls, Etiquette, Lessons and Music

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

| Return to Index |

|

Paper 66 A Selection of Balls from 1807Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 3rd Nov 2023]This paper continues a theme that we've previously studied in earlier research papers. Specifically, this paper investigates a selection of historical balls that were held by the British aristocracy in the year 1807. The events that we'll be studying were all, by chance, discussed in the British newspapers that year. The fact that they were referenced in the press explains how we are able to investigate them today. The only theme that connects these various events is that they were described in the press, and that the descriptions were sufficiently detailed that we can recover some interesting details of the original events. In each case we will discover a partial list of the tunes and dances that were enjoyed, we'll then go on to study those tunes further below. The tunes and dances that we'll consider further in this paper are:

Figure 1. Lady Vernon a portrait c.1790, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1. Lady Vernon a portrait c.1790, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Lady Vernon's BallWe'll begin by considering a ball held in April of 1807 by Lady Vernon (see Figure 1). Lady Jane Venables-Vernon (c.1746-1823) was the second wife of George Venables-Vernon, 2nd Lord Vernon (1735-1813) of Sudbury Hall in Derbyshire. The ball was held at their Park Place address in London, it was ostensibly held in celebration of the Baron's birthday. The ball may in practice have been an opportunity to present their daughter Georgiana to society, she would go on to marry the Honourable Edward Harbord (1781-1835) a couple of years later in 1809. The Morning Post newspaper for the 22nd of April 1807 wrote of the ball (with dance references highlighted in bold): On Monday evening, in Park-place, Lady Vernon gave an elegant Ball and Supper to a large circle of fashionables. The fete was given in honour of Lord Vernon's Birth-day. The magnificent family mansion, second to none in the kingdom, was fitted up for the occasion with more than usual taste and splendour. The floor of the ball-room was painted in water colours by a first rate artist. In the centre of the floor appeared the family arms richly emblazoned. Owing to the Marchioness of Headfort's Concert, and several other fashionable parties, given on the same evening, the company did not begin to arrive till eleven o'clock. About a quarter past eleven the dancing commenced, the ball being opened by Earl Percy And Miss Vernon, to a new tune calledMother Goose, being a selection from the overture to the favourite Pantomime of that name. Among the couples which followed were:- There is much of interest in this passage. First we learn that the dance floor had been painted with watercolours in preparation for the dancing, this is a convention that we have written about before. It was more common to decorate ballroom floors with chalk imagery (which would be destroyed as the dance proceeded), I imagine that a watercolour design would survive a little longer. We also learn that many of the guests attended a concert earlier in the evening hosted by the Marchioness of Headfort; this is not only evidence that guests might attend more than one event of an evening, but also that the hosts might coordinate with each other. One particular tune is named as having been danced at the event, Mother Goose, we'll return to consider that tune in more detail shortly. Next we're informed that there was an attempt to create a second longways set for country dancing. There was insufficient space in which to do so however. We don't know how many couples were able to dance, it's likely to have been between twelve and twenty; there were evidently more guests willing to dance than there was space available in which they could do so. The guests danced throughout much of the night, pausing only for supper around 3am.

Lastly we're told of a particularly memorable Reel of Three being danced by three gentlemen towards the end of the night. The dancers were the 20 year old Henry Fox-Strangways (1787-1858), the 22 year old

Thomas Hay-Drummond, 1785-1866 and the 22 year old Hugh Percy (1785-1847). We've described the Reel of Three in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. It was evidently danced on this occasion with some enthusiasm and energy, we're informed that it was given

Lady Scott's Ball and Supper

Our next event was hosted in June 1807 by Lady Scott. There were several ladies with the title  Figure 2. Viscount Trafalgar c.1807, image courtesy of the University of Glasgow.

Figure 2. Viscount Trafalgar c.1807, image courtesy of the University of Glasgow.

Lady Scott gave a grand Ball and Supper, last night, at her elegant house in Leicester-square. The arrangements were in the highest style of elegance. The Grand Hall was brilliantly lighted by variegated lamps. Supper tables for 120 were laid out in the parlours, and another table, for sixty persons, in the front drawing room. They were set out in the greatest splendour, and lighted by silver branches, and the most beautiful wax vases, with wax lights, which had a most brilliant effect, being the first of the kind invented to resist the heat of a candle. A superb triumphal arch, supported by fancy figures, was placed on the table; various pastry ornaments, were judiciously placed at distances, and had an elegant effect. The curious wax vases, and the arrangements of the table, were executed by Mr Cooke, of Suffolk-street. Three superb drawing-rooms, lighted by diamond-cut-glass lustres, and or-molu branches, bearing lights, displayed the elegant paintings of Sir Joshua Reynolds, with which those superb apartments are adorned. The floor of two of the drawing-rooms were chalked; the one representing aparterre, and the other a Mosaic pavement. A band of music was placed in one of the anti-chambers. At twelve o'clock the ball was opened by the lovely Miss Scott, and Viscount Trafalgar; Miss Scott was elegantly dressed in apple-blossom crape, with garlands of roses, and was joined in a Cotillon by Count Misnard, the Chevalier Boublanc, Miss Walsh Porter, and Miss Boughton; after which followed the new dance, called The Wood Daemon; in which Lady Sarah Spencer and Lady Charlotte Nelson joined. At one o'clock the company sat down to a supper, consisting of soups, and every delicacy of the season; the choicest wines graced the festive board in abundance. There were upwards of 500 persons present; amongst whom were- Once again we read that particular care was invested into the decoration for a ball, this time it's the lighting that was of special merit. Lady Scott is reported to have had the first use of a newly invented variety of wax lights. Two rooms were chalked for dancing, a third held the band. The supper table was elegantly decorated too. Two of the Royal Dukes were in attendance at the ball, Lady Scott evidently had high connections.

Two dances are mentioned as having been enjoyed during the course of the evening. The first was described as being a The second dance to be named was The Wood Daemon, we'll investigate that tune further shortly.

Lady Hume's Ball and Supper Figure 3. Lady Hume a portrait, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Lady Hume a portrait, image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Our next ball was held in July of 1807 by Lady Hume. She was Lady Amelia Hume (1751-1809), the wife of Sir Abraham Hume (1749-1838). The first dance was led off by their eighteen year old second daughter Amelia Hume (1788-1814) together with the 22 year old Hugh Percy (1785-1847) (who entirely exhausted the other dancers at Lady Vernon's ball above). The ball was held at their Berkeley Square address in London. The British Press newspaper for the 3rd of July 1807 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): Lady Hume gave a grand Ball and Supper, on Tuesday night, at her house in Hill-street, Berkeley-square, which were numerously attended. The grand stair-case was lighted by patent lamps, on Egyptian pyramids. The grand ball-room displayed great taste in its arrangements; it was lighted by a superb lustre, with diamond-cut drops and icicles. Lights inor-molubranches were placed on elegant stands; three supper-rooms, on the ground floor, were set out with great elegance; in the first was a horse-shoe table for one hundred persons; valuable China vases, withbouquets, were on the tables, and curious figures intermixed between them;Mother Goosewas well executed in wax. In the other two rooms tables were set out for one hundred more, and the whole lighted by silver branches, bearing lights. The supper was hot, and consisted of every delicacy of the season. At twelve, the ball was opened by Earl Percy and Miss Hume, to the favourite air of The Fairy Dance. After which, Earl Kinnoul and Lady Townshend, the Hon. Captain Hay, and Miss Evelyn, danced the merry dance of Fight about the fire side. At two o'clock the company came down to supper, and at three returned to the ball-room, when dancing recommenced, with Drops of Brandy. It was half past five when the company separated, amongst whom were:- His Royal Highness the Duke of Cambridge, Prince Esterhazy; Duchesses of Northumberland, Gordon, Bedford, Leeds, and Rutland; Marchionesses of Salisbury, Ashburnham, Carhampton, Camden, Dowager Essex, Barrymore, and Talbot; Ladies Townshend, M. Cotton, Smith Burges, G and E Cecil, Glynne, and Metcalf.

On this occasion we're informed once again about the quality of the lighting, also the impressive horseshoe of tables arranged for the guests to dine from. Once again we find a reference to Amelia Hume, who led off the first dance of the evening, would go on to marry John Cust (1779-1853) in 1810. He would go on to become the first Earl Brownlow in 1815, sadly Amelia died in 1814.

Brighton Pavilion BallOur next event was held at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton in August of 1807, under the auspices of the Prince of Wales and his brothers. We've previously studied balls held at Brighton Pavilion in both the years 1808 and 1817, you might like to follow the links to read more. The Daily Advertiser newspaper for the 17th of August 1807 wrote of our event (with dance references highlighted in bold) that:  Figure 4. The Corridor, Royal Pavilion, c.1820. Image courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts

Figure 4. The Corridor, Royal Pavilion, c.1820. Image courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts

The most splendid Entertainment that ever was given at this place, was that at the Pavilion last night, and at which upwards of three hundred distinguished personages were present. Among whom we were only enabled to notice the following:- We read that a whole suite of rooms were used for our ball and that the Egyptian Gallery was employed as the temporary ballroom. The first dance of the ball was led off by the 36 year old William Craven (1770-1825) with either the approximately 10 year old Mary Seymour (c.1798-1848), or her sister the nearly 12 year old Horatia Seymour (1795-1853). They were both daughters of Lord Hugh Seymour (1759-1801) and proteges of Prince George's mistress Mrs Fitzherbert (1756-1837). The Prince had attempted to broker a guardianship proposal for Mary in 1802 following her father's death, if accepted he pledged £10000 to Mary upon her coming of age. It's a little bizarre for a ball to have been opened by a child. We've previously written of a ball held at the Royal Pavilion in 1817 (some 10 years later) that was also opened by, in all probability, Mary Seymour. Our ball was opened to the tune of Off She Goes, we'll investigate that further below. Only twenty couples were involved in the dancing on this occasion as that was all that the room could hold.

Wentworth House FeteOur final event was held in October of 1807 in celebration of Lord Milton's coming of age. It was held in the Yorkshire estate of Wentworth House. The young lord was Charles Wentworth-Fitzwilliam (1786-1857) and the venue was the magnificent Wentworth Woodhouse near Rotherham. The ball was opened by his mother, Lady Charlotte Fitzwilliam (c.1750-1822) with William Cavendish (1790-1858) (later Duke of Devonshire). The Morning Post newspaper for the 26th of October 1807 wrote of the event (with dance references in bold):  Figure 5. Wentworth Woodhouse c.1828 from A Complete History of the County of York by Thomas Allen. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5. Wentworth Woodhouse c.1828 from A Complete History of the County of York by Thomas Allen. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The grand Fete and Ball given at Wentworth House on Tuesday, in celebration of Lord Milton's coming of age, was the most splendid entertainment ever witnessed in Yorkshire. The arrangements for the accommodation of the guests were completed in a most extensive style.

For this event we're given some colourful details about the attendees. Several of them were representatives of prominent families from around the country, most of the 1100 or so guests consisted of land owners from around Yorkshire. Apparently We're only informed of a single country dancing tune that was enjoyed at this event, Madame Catalani's Waltz, we've studied that tune before in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. We will now turn our attention to the named tunes that have been encountered from across our various events.

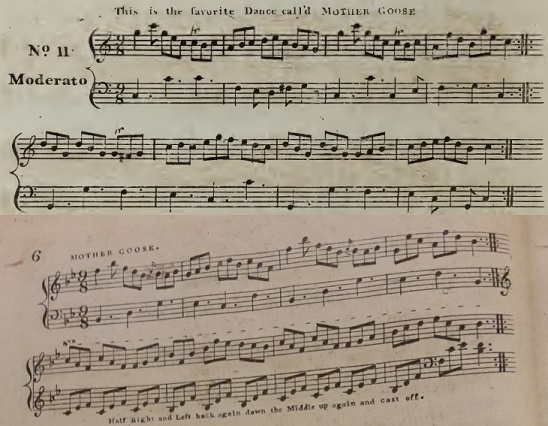

Mother GooseAbout a quarter past eleven the dancing commenced, the ball being opened by Earl Percy And Miss Vernon, to a new tune called Mother Goose, being a selection from the overture to the favourite Pantomime of that name.(Lady Vernon's Ball)  Figure 6. The Mother Goose tune from Ware's score to the pantomime (upper) and Mother Goose from Kelly's New Country Dances For the Year 1808 (lower).

Figure 6. The Mother Goose tune from Ware's score to the pantomime (upper) and Mother Goose from Kelly's New Country Dances For the Year 1808 (lower).

The

The term

Dibdin's

At least four country dancing tunes named Mother Goose were published in London in 1807 and 1808, two of which were directly derived from Ware's score. The most popular of these tunes is readily identifiable, both because it was the most widely published, and also because Ware identified the tune in his subsequently published score with the legend The precise publishing sequence for the tune can't be known, examples issued in London include: Goulding & Co's c.1807 10th Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 4th Number, Clementi & Co's c.1808 5th Book, James Platts's c.1808 7th Number and Kelly's New Country Dances For the Year 1808. It would go on to be named as a popular tune in Thomas Wilson 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and in Edward Payne's 1814 Companion to the Ballroom. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Thomas Wilson's 1809 version. For further references to the tune, see also: Mother Goose (2) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

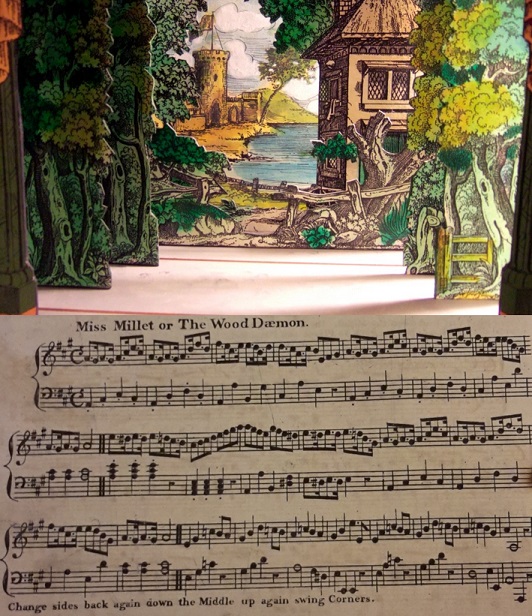

The Wood Daemon / Miss Millet... after which followed the new dance, called The Wood Daemon; in which Lady Sarah Spencer and Lady Charlotte Nelson joined.(Lady Scott's Ball and Supper) Our next tune, The Wood Daemon, was once again adapted from the stage. The origins of the tune are from Michael Kelly's score for the 1807 production The Wood Daemon, Or, The Clock Has Struck. This was a gothic melodrama created by Matthew Gregory Lewis (1775-1818), it would subsequently be renamed in 1811 as One O'Clock, Or, The Knight and Wood Daemon. It was first presented on the 1st of April 1807 at Drury Lane.  Figure 7. A toy theatre scene depicting a set from The Wood Daemon (upper), Miss Millet or The Wood Daemon from Dale's c. 1810 17th Number (lower). Upper image courtesy of Clive Hicks-Jenkins' Artlog.

Figure 7. A toy theatre scene depicting a set from The Wood Daemon (upper), Miss Millet or The Wood Daemon from Dale's c. 1810 17th Number (lower). Upper image courtesy of Clive Hicks-Jenkins' Artlog.

The Morning Post newspaper for the following day wrote:

The composer of the music was Matthew Kelly (c.1764-1826). Several songs from the production were advertised to be available for purchase from Kelly's Opera Saloon some weeks later in May (Morning Herald, 18th May 1807). The Morning Herald newspaper for the 2nd of April 1807 wrote of the score that

It's at this point however that that we encounter a bit of a mystery. A popular tune derived from the Wood Daemon was evidently in circulation but I've yet to find a copy to study. It seems not to have been widely known, at least not under the name we would expect and at our 1807 date. The play would subsequently be revived in 1811 under a slightly different name, and at around that date (possibly a little earlier) a tune named The Wood Daemon did in fact circulate, only it did so under two different names. The first name was The (possibly) first publication of the tune that I can find is located in one of the later editions of Charles Wheatstone's first Selection of Elegant & Fashionable Country Dances, Reels, Waltz's &c.. This work is particularly difficult to date as Wheatstone seems to have reissued it under the same cover multiple times; I've studied two different copies, I suspect that there may have also been a third. I've previously speculated that the two copies that I've studied dated to the year 1808 (or later) and that a different work had first been published under the same name back in 1806. Of the two copies that I've studied, the copy which contains our tune is clearly the later, what's unclear is the original date of publication; it could have been 1808 but it could have been 1810... or later still. You can read more of my attempts to make sense of all this in a previous paper. To further confuse matters, the name of our tune in this work is given as Miss Millet. In other words, the alternative title of Miss Millet could have been the first name under which the best known Wood Daemon tune was issued. That said, Wheatstone may have been obliged to reissue his work following his loss of a copyright dispute in 1812, it's possible that the edition of his work that included Miss Millet may have been issued at this later date, and so the name Miss Millet may in fact have been somewhat later. It's all rather confusing! And it remains a matter of speculation that the tune that was danced at our ball of 1807 is the same as that which became popular around the year 1811. It's not possible to reconstruct a precise sequence of publication for the country dancing tune in London, examples include: Dale's c. 1810 17th Number (as Miss Millet or The Wood Daemon, see Figure 7), Monzani's c.1810 20th Number (as Mrs or Miss Millet), Walker's c.1812 30th Number (as Miss Millet or The Wood Daemon) and in Dublin in W. Power's A Collection of Fashionable Dances for the Year 1812 (as The Wood Daemon, or Miss Millet). The picture that emerges remains uncertain; the stage production was released in 1807 and a tune became sufficiently popular to be danced at our 1807 ball (without being widely published); Wilson referenced the tune as remaining popular in 1809 and several publishers may have issued it around 1810. Wheatstone may have been one of the first to do so, or one of the last to do so; the alternative name for the tune remains unexplained. The tune remained sufficiently popular to have been named in Edward Payne's 1814 Companion to the Ballroom however. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Dale's c.1810 version (see Figure 7).

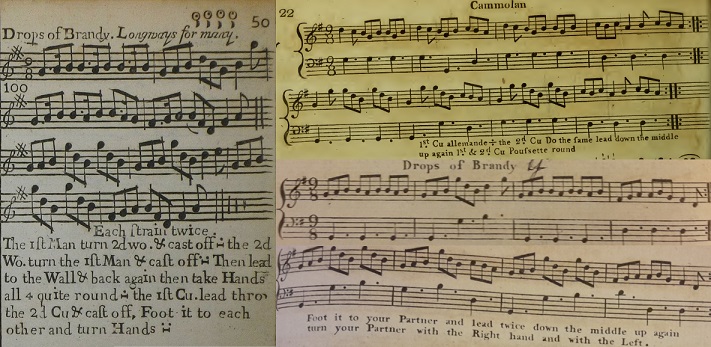

Drops of Brandy / New Drops of Brandy / Cammolan... the company came down to supper, and at three returned to the ball-room, when dancing recommenced, with Drops of Brandy(Lady Hume's Ball and Supper)  Figure 8. Drops of Brandy from Wright's c.1740 Compleat Collection of Celebrated Country Dances (left); Cammolan from William Campbell's 1795 10th Book of New and Favorite Country Dances & Strathspey Reels (right, upper); and Drops of Brandy from William Campbell's c.1796 11th Book of New and Favorite Country Dances & Strathspey Reels (right, lower).

Figure 8. Drops of Brandy from Wright's c.1740 Compleat Collection of Celebrated Country Dances (left); Cammolan from William Campbell's 1795 10th Book of New and Favorite Country Dances & Strathspey Reels (right, upper); and Drops of Brandy from William Campbell's c.1796 11th Book of New and Favorite Country Dances & Strathspey Reels (right, lower).

Our next tune is something a little different. It's a tune with a publication history spanning from the 1740s through to the date of our 1807 ball, and beyond. This alone would make it unusual, very few country dancing tunes remained in fashion over such a timescale. The vast bulk of the tunes that we've studied in previous research papers were of recent publication at the date that they were danced, they're rarely more than a decade old. Whereas Drops of Brandy was a veteran tune, something that the dancer's grandparents could have danced to back in their own youth! Not only that, but several minor variations of the tune circulated under different names thereby adding another layer of confusion. The first publication of the tune that I can find is in the first volume of Wright's c.1740 Compleat Collection of Celebrated Country Dances under the name Drops of Brandy (see Figure 8, Left). It also appeared in the first volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances shortly thereafter, still under the same name. It would then resurface a few years later in the c.1765 second volume of Thompson's Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, still under the same name. These early versions of the tune were essentially the same. These initial publications of the tune were all issued in London, some later publications would go on to emphasise an Irish origin for the tune. It may indeed have been of Irish origin. The tune is written in 9/8 time signature, this rhythm was widely referred to as an Irish rhythm, whether the tune itself genuinely derives from Ireland is (as far as I know) unknown.

The next publishing boom for the tune occurred in the 1790s and 1800s. It would appear in two different c.1795 works: in Longman & Broderip's c.1795 Fifth Selection of the most admired Dances, Reels, Minuets & Cotillons (still as

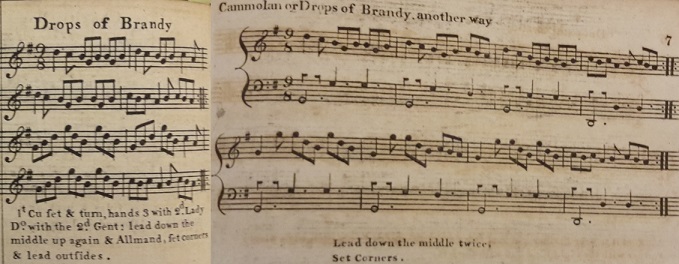

To complicate matters further still, another version of  Figure 9. Drops of Brandy from Bland & Weller's Annual Collection of Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1797 (left); and Cammolan or Drops of Brandy, another way from Dale's c.1800 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c. (right).

Figure 9. Drops of Brandy from Bland & Weller's Annual Collection of Twenty Four Country Dances for the Year 1797 (left); and Cammolan or Drops of Brandy, another way from Dale's c.1800 Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c. (right).

Next we come to an interesting publication of uncertain date issued by Joseph Dale somewhere around the year 1800. It's named Dale's Selection of the most favorite Country Dances, Reels, &c.. This publication included both Drops of Brandy (in the arrangement that was used by both Longman and Campbell) and also a danced named Cammolan or Drops of Brandy, another Way (as had previously been arranged by Campbell, See Figure 9, Right). Finding both tunes co-located in the same work hints that the public continued to understand them as separate tunes. Their similarity was sufficiently close that Dale renamed the second tune to emphasise that this was no mere accident, the Cammolan tune was just the Drops of Brandy tune arranged

Back in London it would appear in many more publications. Preston included the In addition to a rich publishing history the tune was also danced at a good number of society balls in the 1800s. Examples include The Countess of Leicester's Ball of 1800 (Caledonian Mercury, 27th of March 1800), a ball held by the Duke of Clarence in 1806 (Saunders's News-Letter, 8th of February 1806) and The Lady Mayoress's Ball also in 1806 (Morning Advertiser, 9th of April 1806). It was danced at several events of 1807 in addition to Lady Hume's Ball and Supper; examples include a ball to celebrate the opening of the South London Water Works (The Star, 17th of June 1807) and the annual meeting of the Northern Shooting Club in Aberdeen (Morning Post, 16th of October 1807). It was also danced in 1809 at a ball held by John Mattet, Esq near Wimborne (The Star, 31st of January 1809).

The title of the tune was sufficiently humorous to be used as a punchline in a number of jokes. The Chester Chronicle for the 25th of April 1800 wrote:

Our tune was popular across the late 1790s and 1800s, it may have fallen from favour thereafter. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's 1795 version of For further references to the tune, see also: Drops of Brandy (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

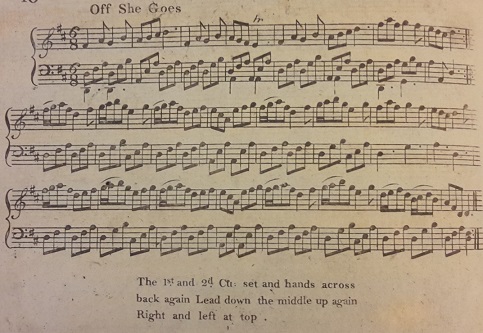

Off She GoesThe Ball, we believe, was opened ... with the lively air of Off she goes!.(Brighton Pavilion Ball) Our next tune danced in 1807 is named Off She Goes. It's a tune that was popular across the first decade of the 19th century. The first publication of the tune (that I can identify) was issued in Edinburgh in Thomas Calvert's c.1799 A Collection of Marches & Quick Steps, Strathspeys & Reels, it was printed under the name Of Shew Goyes. Thereafter the tune became popular in London, it would be published by a myriad of London based music shops between about 1804 and 1809.  Figure 9. Off She Goes from Campbell's c.1805 20th Book.

Figure 9. Off She Goes from Campbell's c.1805 20th Book.

The tune's precise sequence of publication in London can't be known but examples include: Dale's c.1804 4th Number, Campbell's c.1805 20th Book, Hodsoll's collection of 12 Most Fashionable Country Dances for the Year 1805, Preston's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1805, Goulding's c.1805 7th Number, Thompson's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1805, Walker's c.1806 10th Number, Hamman's c.1806 1st Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1806 1st Number, Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favourite Country Dances, James Platts's c.1807 1st Number, John Paine's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1807 and Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1808 1st Book. The tune was also mentioned in both Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and in Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball Room, it also appeared in Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. It was evidently popular.

Back around 1804 there was an unusual publication of a tune named The tune was certainly popular at society balls. It was danced at a ball held by the Earl of Dorchester in 1803 (Salisbury and Winchester Journal, 19th of September 1803), at Ramsgate in 1804 (Morning Post, 31st of July 1804), at a ball held at Romney Races in 1805 (Morning Post, 31st of August 1805), at a ball held by James Farquharson in 1805 (London Courier, 17th of October 1805), a ball held by The Duke of Clarence in 1806 (The Sun, 3rd of February 1806), the Lady Mayoress's Ball in 1806 (Morning Advertiser, 9th of April 1806), and of course at our Brighton Ball of 1807. It would also be danced at a ball held by the Prince Regent in 1813 (Morning Post, 14th of May 1813) and a second event held by the Prince also in 1813 (Morning Post, 27th of August 1813). Perhaps it was a favourite tune of the Prince. The tune is much better known today as a nursery rhyme under the name Humpty Dumpty. It's unclear at what date the tune became associated with the rhyme, it might very well have been a Regency era combination. We've previously encountered Off She Goes in another paper when investigating the improbable claim that George McFarren composed the tune. You might like to follow the link to read more. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Campbell's c.1805 version, of Preston's 1805 version and of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version. For further references to the tune, see also: Off She Goes (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

ConclusionWe've encountered a variety of tunes being danced to across this collection of 1807 Balls. We've encountered tunes derived from stage productions such as Mother Goose and The Wood Daemon, tunes that have lived on into the modern era as Nursery Rhymes (Off She Goes) and old favourite tunes brought back into fashion (Drops of Brandy). Each tune has its own unique story. If you wanted to host an event themed around the year 1807 then any of these tunes would be very suitable to use. We'll leave the investigation there however, if you have any further information to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2024

All Rights Reserved