|

Paper 51

The Country Dances of George McFarren, 1808

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 2nd August 2021, Last Changed - 24th September 2023]

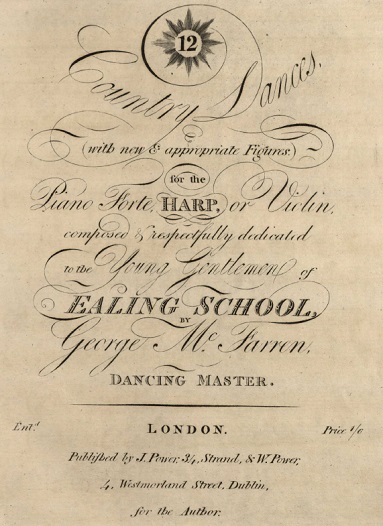

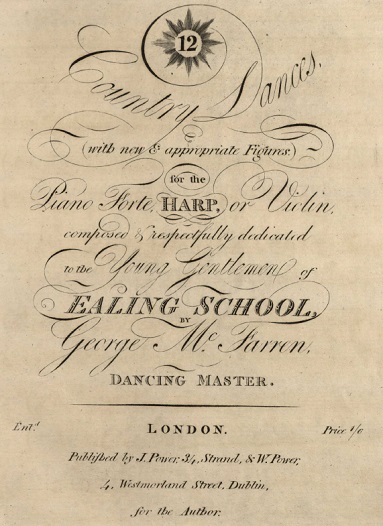

George McFarren (1788-1843) is known to history as a minor dramatist and theatrical manager, in this paper we'll consider his early career as a Dancing Master and an unusual collection of Country Dances that he issued in 1808 (see Figure 1). These dances are notable for being choreographed to a far greater extent than was common at this date, their content will be of interest to anybody who studies the country dances of the early 19th century.

Figure 1. McFarren's collection of 12 Country Dances dedicated to the Young Gentlemen of Ealing School, 1808.

The dances we'll investigate in this paper are:

The early professional life of George McFarren (1788-1843)

Not much has been written of McFarren, most of what I can find was recorded by his son Sir George A. McFarren in a memorial sketch published in 1877 in The Musical World. The son wrote of his father that:

From 1788 to 1843 his life was of almost ceaseless activity. In early childhood he showed a talent for versification, to which a far higher definition would not be misapplied; and some stanzas dated on his thirteenth birthday, evince depth of thought and power of words betokening ripest years. While a schoolboy he wrote a tragedy, which was acted by his mates, with the assistance of young Edmund Kean, then known by the name of Carey, with the sanction of the afterwards famous actor, Liston, usher at that time in Archbishop Tennyson's school - the scene of the performance.

He evidently showed sparks of talent for theatre as a youth, two subsequently famous actors were recorded to be within his circle. The account continues:

My father played on bowed instruments so well as to sustain either of the parts in a violin quartet. He had some facility on the pianoforte, on which, and on the fiddle, he was my first instructor. Would he had had an apter pupil! He composed songs of merit, and many country-dance tunes that had great popularity. One of the latter, which may now sometimes be heard on street organs - Off she goes - has been claimed as a national Irish melody; and this says more for the merit of the tune than the acumen of the editor.

We'll learn more of McFarren's Country Dances shortly. I can't pass over this charming fragment of information without commenting on the composership of Off She Goes . This tune was indeed popular, it was widely published in London from around 1804, it went on to feature in at least one Royal ball of 1813 (Morning Post, 14th May 1813). McFarren would have been around 16 years of age when the tune surfaced; he may have sold it to one of London's music shops for a small fee, receiving (as was so often the case) no credit for having done so. It's rare that the original composer of Country Dancing tunes was ever credited, such tunes were usually considered to be of little musical merit, the niceties of copyright registration were reserved for more serious musical compositions. That all stated, McFarren simply can't have been the composer of this tune unless he wrote it before the age of 11. It was published from as early as 1799 in Edinburgh in Thomas Calvert's Collection of Marches & Quick Steps, Strathspeys & Reels under the name Of Shew Goyes . It seems more likely that McFarren arranged the version that saw popular interest in London from 1804 and that his son never comprehended this subtlety. Versions of Off She Goes can be found in Cahusac's 24 for Country Dances for 1804, Thompson's 24 for 1805, Preston's 24 for 1805, William Campbell's c.1805 20th Book, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book and Button & Whitaker's c.1806 1st Number (amongst many others).

The account continues:

Music would have been his profession had he not met with a fashionable teacher of dancing - Bishop by name - who offered to make him a gentleman instead of a fiddler, and, accordingly, took him as an apprentice. Here was a disparity between name and nature, the calling and the called; and, I earnestly believe, here was a consequent loss to music. Quick in conception and sanguine in enterprise, he promptly formed the plan of a work or of an action, and eagerly pursued it. So, when eighteen, he quitted his parental home, rented a spacious room, and opened a school for dancing.

McFarren evidently met the successful dancing master Henry Bishop (d.1809) and studied under him, probably for several years as an apprentice. McFarren's country dance choreographies are quite distinct and presumably they were influenced by Bishop's own style. Bishop had published some dance collections in the late 18th Century, not much is otherwise known about him. We're informed that McFarren became a Dancing Master at age 18 which would be around the year 1806. He published his collection of 12 Country Dances (with new & appropriate Figures) for the Piano Forte, Harp or Violin, composed & respectfully dedicated to the Young Gentlemen of Ealing School in 1808 (see Figure 1, it was registered at Stationer's Hall for copyright purposes in December 1808), presumably many of his students studied at the Great Ealing School (see Figure 2). Indeed, he may himself have been employed to teach dancing at the school. We'll consider this collection of dances further shortly. If McFarren was teaching at Ealing then that would have been a prestigious appointment; it was considered to be one of the best schools in England, Louis Phillipe of France (later the King of France) even taught mathematics and geography there prior to the Bourbon restoration of 1815.

Little more is recorded of McFarren's time as a dancing master. The Dictionary of National Biography adds that Macfarren married, in August 1808, Elizabeth (b. 20 Jan. 1792), daughter of John Jackson, a bookbinder, of Glasgow, who had settled in London. . It continues: in 1816 he visited Paris, where he had lessons in dancing from the best teachers. His natural bent was, however, towards the stage, and on 28 Sept. 1818 his first publicly performed dramatic work, Ah ! what a Pity, or the Dark Knight and the Fair Lady, was given at the English Opera House . He visited Paris in 1816 presumably to receive tuition in the freshly popular Quadrille dance form, but his interest in dancing waned. He instead published at least one major stage production most years of his life thereafter. His time as a dancing master was left behind him, his true calling to the stage had begun.

Choreographed Country Dances c.1808

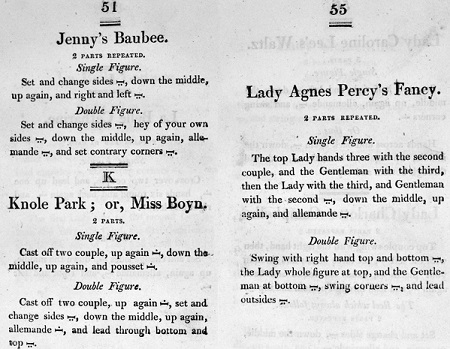

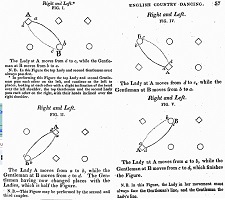

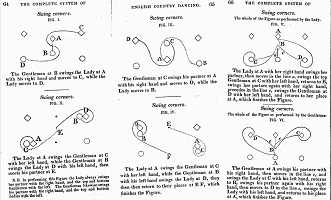

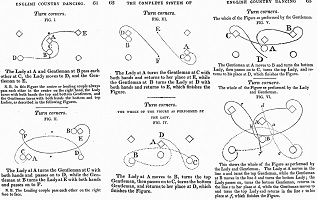

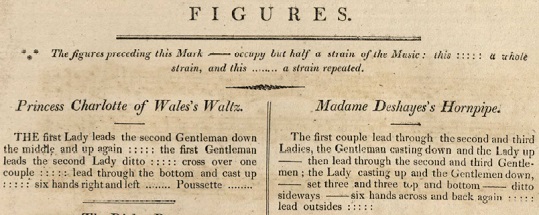

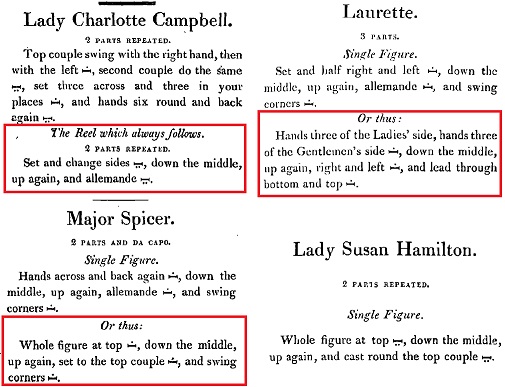

Figure 3. Example pages from Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore showing choreographed Country Dances in both single and double arrangements

We've described McFarren's Country Dances as being choreographed but what does that mean? One can point to thousands of Country Dances that were published in the early 19th Century that contain both a tune and suggested figures, one might consider all such publications to be choreographed . The problem is that the average quality of such publications was so low that it's uncertain that anybody invested effort into their combination. Many such dances don't work (or they only worked by chance). For example, a published set of dance figures may require three strains of music while four have been provided, the reader has to decide for themselves how to manage that oddity. A small minority of country dancing publications from the early 19th century are quite different; they have figures that perfectly fit the music, are internally consistent in their timing and use of terminology, are associated with a named arranger (perhaps even a Dancing Master) and rise above the uninspired dances that were typically published. McFarren's dances fit this definition. The word choreographed , in this fairly minimal context, implies that an arrangement probably had some thought applied to it and that the choreographer had a reputation to protect.

Aside: most country dance collections were issued by music publishers, often in an inexpensive format with minimal effort invested. The dance figures sometimes show evidence of having been allocated almost at random. For example, we've previously investigated the country dances published by Charles Wheatstone; we found strong circumstantial evidence that some of his dances published in 1812 had copied figure sequences previously published by Skillern & Challoner around 1806. The reuse of earlier figures seems to have been done without a basic comprehension of the source material. The transcriber could perhaps have been a junior member of staff who was simply tasked with an anything will do mandate to fill the paper. This is of course a matter of speculation.

The convention in the Assembly Rooms in the early 19th century was for the leading couple, typically the leading lady, to Call a Country Dance. This involved selecting the tune to be danced and the figures to dance to that tune; the leading couple could select any figures they liked, there was no expectation (except in a small minority of cases) that a well known combination would be selected. The experience of performing a country dance could be quite different from one evening to the next. Given this convention one might wonder why suggested dancing figures were published at all. The lack of effort that was invested in most published collections may be a product of this lack of significance to the figures, they were at most a suggestion of what could be danced. The story isn't that simple however, we must also consider who the published collections were aimed at. Most of the cheap dance collections were sold to the general public, people who were unlikely to lead off a dance at the elite Assembly Rooms. Purchasers may have used such publications in the privacy of their own homes, perhaps they would have attempted the suggested figures themselves, working combinations of tune and figure must have had a purpose.

What is certain is that a market existed for choreographed country dance arrangements, somebody wanted them. The Dancing Master Thomas Wilson published his Treasures of Terpsichore in 1809 (see Figure 3), this book contained nothing but suggested figures for popular tunes; there was no music included, whoever bought a copy did so just for the suggested figure sequences. We might therefore describe Wilson's arrangements as being choreographed. Wilson issued a second edition in 1816 and supplements for both 1810 and 1811. They first edition and supplements presumably sold well enough to justify the 1816 second edition. Wilson was a prolific advertiser, his customers were the type of people who read the daily newspapers - relatively ordinary people. Wilson was also a prolific choreographer of country dances, he published thousands of combinations of tunes and figures over around 15 years from 1809. His arrangements were reliable and consistent, they were also quite different to the typical Country Dances of the later 18th Century. An abiding question in the study of social dance history is the extent to which Wilson's choreographies were representative of the entire industry at the same date. The low quality of many dance collections (at this date) makes it difficult to provide an authoritative answer: if other collections are different to those of Wilson then that could imply that Wilson was a maverick, or it might only imply that the other collections were themselves unreliable. McFarren's choreographed dances, influenced as they presumably were by Henry Bishop, will provide fresh insight into this question of the value of Wilson's works. If McFarren's dances share a similar structure to Wilson's dances then we might consider Wilson's books to be representative of London's social dance industry in general.

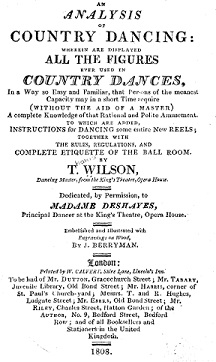

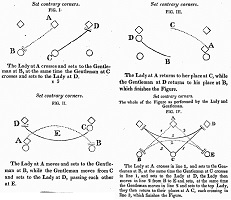

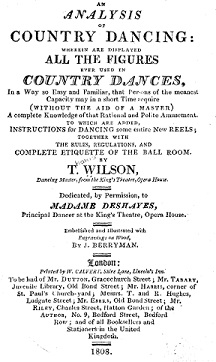

Figure 4. Thomas Wilson's 1808 first edition of An Analysis of Country Dancing

Thomas Wilson published his first book on Country Dancing in 1808, it was his An Analysis of Country Dancing (see Figure 4). This book was an encyclopedic work that aimed to document everything that there was to know about Country Dancing at that date. Analysis (as I'll sometimes refer to it) saw extensive clarifications from several new editions over the following decade, most notably in the 1811 second edition. It was subsequently extended and enhanced as The Complete System of English Country Dancing, it was published in its final form around the year 1820. Wilson documented his system for arranging dances within this series of works, he included extensive notes on how to dance the various figures. Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore is best interpreted with a copy of his 1808 Analysis of Country Dancing, or its successors, to hand. Most apparent ambiguities in Wilson's printed dance arrangements are resolved by reading Analysis. His terminology is often surprising (for example he used Right and Left and Lead Down the Middle to mean something different to what many modern readers might naively expect) but he applied his own terminology consistently. His system did evolve over time however, Wilson was still refining his ideas at our date of 1808. As we study McFarren's dances we'll be considering how consistent they are with respect to Wilson's publications, especially those published in 1808 and 1809; we'll thereby gain confidence in answering the broader question of how representative Wilson's system of Country Dancing was of the rest of the industry.

Wilson, in his publications, typically offered two sets of a figures that could be used with any given tune. He would often provide both a single arrangement of figures (where the tune is played through once) and a double arrangement (where the tune is repeated, see Figure 3). Double arrangements lend themselves to more challenging figure sequences. Wilson explained his reason for doing this in his introduction to the Treasures of Terpsichore, along with his theory of why Country Dancing had lost (by the date at which he was writing) the variety it had once possessed: For my own part, I really believe it to have originated in an attempt at simplicity, an effort to do every thing with the greatest apparent ease. But it should be remembered, that though simplicity is the greatest ornament of beauty, that simplicity without beauty is mere insignificance. ... I do not wish to be understood that I would recommend long figures for all companies; no, I consider short figures for large assemblies far more appropriate than long ones, not being so fatiguing, and giving more of the company an opportunity to call Dances. Not but any Lady, if she be so disposed, has a just right, even in a large assembly, to call a Dance to a double figure, unless previously informed to the contrary by the Master of the Ceremonies. . The more challenging dances, such as Wilson's double arrangements, were inappropriate for Regency era Assembly Rooms as they would take too long to dance through. A leading couple was expected to dance to the bottom of an entire longways set, back to the top, and down a second time. This might take 50 or more iterations of the music for a single dance! McFarren's arrangements tend not to employ Double figures (though there are some examples in the collection), despite this they remain relatively exotic.

McFarren's collection of dances were dedicated to the Young Gentlemen of Ealing School , these boys were presumably his students. It's possible, perhaps likely, that McFarren was employed by the school. Choreographed Country-Dances would have found a more immediate use at a dancing class than they had in the Assembly Rooms, they would offer a challenge that the scholars could perfect and display at the dancing master's end-of-season ball. These end-of-season events were also referred to as a dancing master's ball , they were an important part of dance tuition in the early 19th century. The public, primarily (one assumes) the parents of the pupils, would buy tickets to watch the children demonstrate their prowess; several programmes from such events held elsewhere in the country still survive. The more talented children might perform solo or duo dances, perhaps hornpipes or stage dances; other students might display a Country Dance - perhaps a more exotic Country Dance than the typical fare. I suspect that McFarren's collection of dances were intended for use in his classes, his pupil's parents were probably encouraged to purchase a copy of his publication to aid the children in their study. The same was probably true of Wilson's more exotic dances, they were likely used in his own classes more than anywhere else. Choreographed and Double arrangements of dances were primarily for private use rather than general social dancing, they probably wouldn't be danced for thirty solid minutes as might occur at an Assembly Ball.

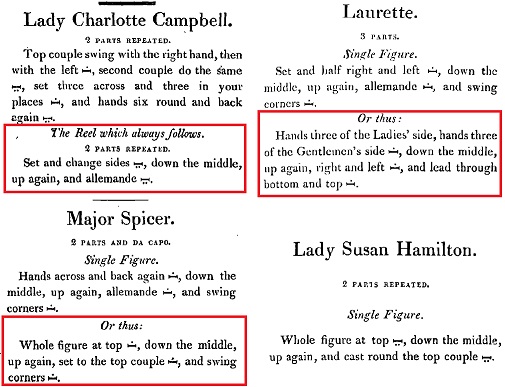

McFarren's Country Dances

McFarren is only known to have published a single collection of dances, his 1808 12 Country Dances (with new & appropriate Figures) for the Piano Forte, Harp or Violin, composed & respectfully dedicated to the Young Gentlemen of Ealing School (see Figure 1). The collection spans 6 sheets of paper, four consist of music, one of dance figures and there's also a cover. The tunes are not known, at least by me, from other sources. McFarren probably did compose the tunes himself just as he claimed on the cover. The tunes are adequate for dancing, each is presented with both a treble and bass line and is arranged for the piano or violin. His music is reasonable but of no greater merit than the many other dance tunes that circulated in London at a similar date. I've no evidence of any of these tunes being danced socially outside of McFarren's own academy, they weren't widely known.

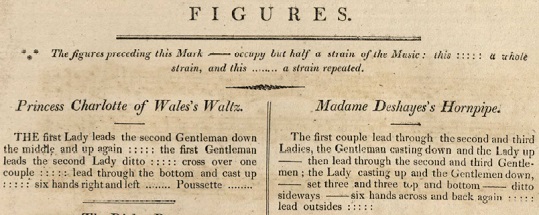

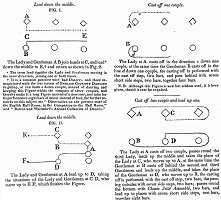

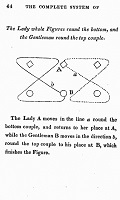

Figure 5. The top of McFarren's page of dance figures

The associated dancing figures are more interesting. McFarren employed an uncommon convention for indicating which figures to dance to each strain of music; he explained: The figures preceding this Mark ----- occupy but half a strain of the Music; this ::::: a whole strain, and this ..... a strain repeated (see Figure 5). Strain markers were nothing new of course, an equivalent system of dotted-bars as used by Thomas Wilson can be seen above in Figure 3. The important observation concerning McFarren's system is that he used it both consistently and correctly; he (like Wilson) evidently knew exactly what he was doing. The same can't always be said of other publications. I've studied dance collections before where the strain markers, if present, are scattered somewhat randomly as though the author had no comprehension of how to use them. For example, we've studied the dances of William Campbell in a previous paper; Campbell's collections are spoiled by his inconsistent use of strain markers. McFarren's system was simple, easy to print and easily explained to the reader. McFarren's dances are more reliably arranged than anything issued by Campbell.

The figures themselves are a mixture of both the interesting and the banal. A rich variety of figures can be detected across the collection. The collection may have been arranged so as to demonstrate as full a repertoire as possible. It would be possible to teach most of what a pupil would need to know of Country Dancing using this collection alone. It seems probable that this is what McFarren intended. We'll discover that most (but not all) of McFarren's figures were also described by Thomas Wilson in his 1808 Analysis of Country Dancing and its successors, we'll comment on the specifics as we review the individual dances.

McFarren studied under dancing master Henry Bishop. I only know of a single collection of Country Dances published by Bishop, they were his Six Minuets and Twelve Country Dances for the Year 1788. Bishop's collection were issued some 20 years before McFarren's, the prevailing trends in country dancing were different at these dates such that a direct comparison between the two collections is unhelpful. Bishop's dances do employ correct and consistent strain markers and the complicated figures are explained, this is consistent with what we'll see in McFarren's collection; but there's no obvious stylistic link to McFarren's collection. We can infer that Bishop was a reliable choreographer and that he trained McFarren well, we can't be certain that Bishop would have approved of McFarren's arrangements.

Signature Elements of Wilson's System of Country Dancing

A goal of this paper is to compare McFarren's dances to Wilson's system of country dancing. We should first review some of the distinguishing characteristics of Wilson's system, especially those elements that can be detected from a published choreography; this is what we will be looking for in McFarren's dances. Wilson's system is notable for being different to that of the later 18th century, an outstanding question for scholars is the extent to which Wilson's system was representative of early 19th century London in general. Wilson may not have been the appointed spokesperson for his generation but was he generally reliable in his pronouncements? Wilson published more on the subject of country dancing than any writer had ever achieved before his time (and quite possibly since), but did he document the mainstream of country dancing at his date?

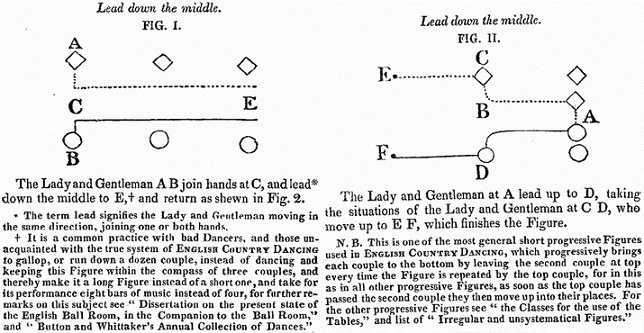

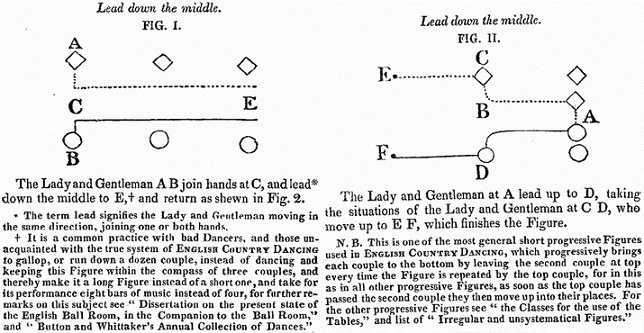

Figure 6. Wilson's short Lead down the middle figure

The signature element in Wilson's system of country dancing is his leading figure (see Figure 6). In Wilson's system the lead down the middle is a short-figure, it employed half the music of a typical 18th century dance. Wilson's leading figure involves going down the distance of two couples, returning one place and dropping into second position, there's no casting involved. Wilson would follow a lead with another short figure such as a two-hand turn. This leading figure is important as it's relatively easy to spot a short-lead followed by another short-figure within a published dance, especially when the choreographer uses unambiguous and reliable strain markers. If we find that combination then the dance might be considered to be Wilsonian in form. If we instead find a long-measure lead with either an implicit or explicit cast then it's a non-Wilsonian arrangement.

Other important figures include the Whole Pousette , in Wilson's system this is a progressive figure (though he only became consistent in this respect a little later into his career, he sometimes featured a non-progressive Pousette in his c.1809 works). His Right and Left is also relatively recognisable, it was consistently a short figure, not the long measure figure that might otherwise be expected. These can also be markers of Wilsonian style country dancing.

Then there's the general vocabulary of dancing; terminology, word combinations, the range of non-trivial figures used. If the figures are broadly consistent with Wilson's system then a dance might be described as being Wilsonian in style even in the absence of a clear marker figure.

There are many other Wilsonian figures but they can be difficult to detect. If, for example, a choreography calls for lead outsides then it's impossible to know whether a Wilsonian or a non-Wilsonian figure was intended, there's insufficient context to say. Occasionally a published notation will explain an otherwise vague figure in sufficient detail to disambiguate what was intended. For example, McFarren's The What d'ye call it? employs a short figure named allemande dos a dos ; there are many different figures that have been described as an allemande , the dos a dos suffix removes the ambiguity, this is probably a Wilsonian allemande figure.

When I reconstruct a dance I use the presence of signature Wilsonian figures to inform the modern arrangement; if a dance (or collection of dances) is broadly Wilsonian in other respects then I'm inclined to use Wilsonian figures throughout. My experience has been that Wilsonian style can be seen in the better quality dance publications of the early 19th century, especially those issued by other dancing masters... but what will we find in McFarren's dances?

What follows are arrangements of each of McFarren's country dances with an investigation of each figure used therein. The music and figures have been transcribed from the source document. Where possible we've included images and explanations from Wilson's various books to describe how the figures are to be danced. In each case there is a link to our animation of the dance, you might like to watch the animation to help understand the reconstructed arrangement.

Princess Charlotte of Wales's Waltz

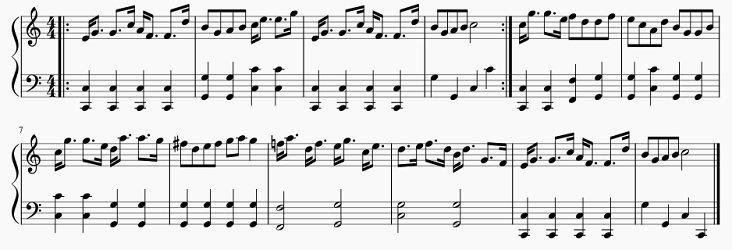

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The first tune in the collection is named Princess Charlotte of Wales's Waltz. The dedicatee was the 12 year old Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796-1817), she was the daughter of Prince George and the second in line to the British throne. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The first Lady leads the second Gentleman down the middle and up again ::::: the first Gentleman leads the second Lady ditto ::::: cross over one couple ::::: lead through the bottom and cast up ::::: six hands right and left ..... Pousette .....

This dance is a triple minor as three couples are required in each minor-set. It's the longest dance in the collection at 64 bars per iteration, it's also the only Waltz in the collection.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-16 |

|

The first Lady leads the second Gentleman down the middle and up again, the first Gentleman leads the second Lady ditto

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This leading figure is uncommon, most leading figures involve the top couple leading down together whereas this figure involves taking a member of the second couple down the set. Wilson did describe this figure in his various books on Country Dancing, but it's not a figure that he often employed in his own arrangements. One area of uncertainty is the manner of the leading - I tend to think that a Wilsonian lead involves galloping down the set (take two hands with your partner and slip sideways relatively quickly down the middle of the set), it's a subject we've discussed in more detail in a previous paper.

Galloping to a waltz rhythm (as in this dance) can be uncomfortable, it's unclear whether Wilson, McFarren or anyone else would intend for that to happen. Dancers might like to experiment with whatever style of leading is comfortable for them. What is clear is that this figure should end with everyone in the same position in which they started the figure, there is no casting involved. |

B 1-8 |

|

cross over one couple

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The top couple cross and cast below the second couple (who move up). What's uncertain is whether they should also half two-hand turn back to their own sides; the subsequent figures work better if they do so I suggest adding a half turn. Alternative arrangements are possible however.

|

B 1-8 |

|

lead through the bottom and cast up

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The top couple (who are now in middle place) join hands and lead through the bottom couple and cast back into progressed positions. If the half two-hand turn was omitted in the previous figure then the first couple can use this figure as an opportunity to return back to their own side of the set.

|

CC 1-16 |

|

six hands right and left

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This figure is almost certainly that described by Wilson under the title Hands six round , everybody joins hands within the minor-set and rotates once around and then back again. McFarren's meaning isn't entirely obvious however, it's possible that he intended a six hands across figure; his instruction of right and left (which implies a direction of movement) perhaps makes more sense with this second interpretation, whereas taking the circle around to the right and back to the left is contrary to the usual conventions. Wilson's Hands six round figure explicitly circles to the left and then back to the right. Either interpretation is possible. Six hands across is a highly unusual figure and therefore, I think, less likely to be what McFarren intended.

|

DD 1-16 |

|

Pousette

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This final figure of this dance is the pousette , it goes once around such that the dancers end the figure in the same position from which they started. We've described the pousette in more detail in another paper. One area of confusion with this figure is that Wilson regularly described it as a Half Pousette , for Wilson a Whole Pousette was a progressive figure that went round one-and-a-half times. McFarren, as with most earlier arrangers of dances, evidently considered a Pousette to be non-progressive. Wilson too would occasionally use the term Pousette for a non-progressive figure starting from progressed places, see for example his 1809 single arrangement of Knole Park in figure 3.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. With the exception of a few terminological variations we've seen that this particular dance is quite consistent with how Thomas Wilson described the figures for Country Dancing. It's not entirely consistent with how Wilson documented figures from around 1811 onwards, it is reasonably consistent with his works of 1808 and 1809.

The Dicky Box

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The second tune in the collection is named The Dicky Box. The title refers to the seat at the back of a carriage typically used by the owner's servant. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Hands three on the Ladies' side, the second Lady passes under the first couple's arms ::::: Ditto on the Gentlemen's side, the second Gentleman passes under ditto ::::: lead down the middle, up again ::::: right and left :::::

This dance is a duple minor as only two couples are required in each minor-set. Each iteration of the dance involves 16 bars of music in 9/8 measure.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-8 |

|

Hands three on the Ladies' side, the second Lady passes under the first couple's arms; Ditto on the Gentlemen's side, the second Gentleman passes under ditto

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This dance, much like the preceding example, starts with an uncommon figure that was described by Thomas Wilson but that is rarely found within his own arrangements. Wilson didn't specify which direction the hands three figure should take but convention suggests that it is to the left (both times).

Country Dances were usually arranged for the pleasure of the leading couple, it's therefore unusual that the leading couple

in this figure are instructed to simply make an arch while the second lady or man passes under. The leading couple might perhaps have retained each other's hands while turning away from each other after the second lady (or man) has passed under, this results in a more complicated (and perhaps enjoyable) second half of the figure. In this manner the first lady almost follows the second lady through the pass under section of the figure, then the first man follows the second man in the next section. Neither McFarren nor Wilson hint that this variation is to be danced but it makes the figure more interesting for the first couple and is something that dancers might like to employ.

|

B 1-4 |

|

lead down the middle, up again

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

Wilsonian leading figures are half-figures, they involve half the amount of music of a typical 18th century leading figure and also omit the subsequent cast . McFarren's leading figure, at least in this dance, appears to be arranged in the same way. I therefore suggest that the first couple use a galloping side-ways lead returning to second place as the second couple move up. We've discussed the Wilsonian leading figure in more detail in a previous paper

|

B 1-4 |

|

right and left

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

A Wilsonian Right and Left figure involved interleaved corners crossing and crossing home, it's not the square hey figure that many dancers would expect today. Wilson's figure was a half-figure; much like his down the middle figure it would use half the music that the equivalent figure of the later 18th century would require. McFarren's figure employs the same half-measure of music that Wilson favoured, it therefore seems likely that McFarren intended the same Right and Left figure to be danced as Wilson. We've discussed Wilson's Right and Left figure in greater detail in a previous paper.

The top lady changes places with the second man in the first bar of the music; then the top man changes places with the second lady; then the first corners swap back, then the second corners cross back. The second corners should begin moving shortly after the first corners such that all four dancers are in motion together.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance seems to be arranged consistently with Wilsonian principles, both the terminology and the internal timing of the figures are as Wilson prescribed for his own dances. The initial figure is known from Wilson's books though not one that he regularly employed himself, other than that it might easily be one of Wilson's own dances.

The Lady's Choice

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The third tune in the collection is named The Lady's Choice. The title might refer to the convention used at the Assembly Rooms whereby the top Lady would choose the tune and figures to be danced. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The two Ladies lead through the two Gentlemen, who pass into the Ladies' places ::::: then the Gentlemen lead through and the Ladies pass into their places ::::: lead down two couple and cast up one ::::: hands four round at top

This dance is a triple minor in that three couples are required in each minor-set, the bottom most couple will have no activity however. Each iteration of the dance involves 16 bars of music in common time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-8 |

|

The two Ladies lead through the two Gentlemen, who pass into the Ladies' places; then the Gentlemen lead through and the Ladies pass into their places

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This figure appears to be a minor variation of the figure that Wilson named The Three Ladies and the three Gentlemen set and lead through ; Wilson's figure involves three couples rather than McFarren's two and Wilson's involves explicit setting as part of the figure. The setting is important to the timing of the figure, without setting there could be too much music for McFarren's figure to work, I therefore suspect that the setting is implicit and that McFarren intended it to be there (as we saw with the half-two-hand-turn in Princess Charlotte of Wales's Waltz). An argument could be made for using the Wilsonian Set and Change Sides figure here, it's possible that this is what McFarren had in mind and it is found far more frequently in Wilson's own arrangements, but the similarity in name with The Three Ladies and the three Gentlemen set and lead through makes this less likely.

I suggest that the top two couples set, then the two ladies pass between the two men as all four swap sides; then repeat, only this time the two men return passing between the two ladies.

|

B 1-4 |

|

lead down two couple and cast up one

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This figure appears to be a minor variation of the figure that Wilson named Lead down and cast up ; Wilson's figure involves casting back to the top whereas McFarren's figure only involves casting up one place, otherwise it will be very similar. I would forego the galloping style of leading for this dance in favour of a forward movement and a simple cast to the middle as the second couple move up.

|

B 1-4 |

|

hands four round at top

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The top two couple join hands and circle once around.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is arranged somewhat consistently with Wilsonian principles; the initial figure appears to be a variation of a figure that was documented by Wilson, the leading figure is also uncommon. Neither of these figures is fundamentally at odds with Wilson's general system for Country Dancing, though it would be unusual if found in a Wilsonian collection.

Ealing School

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The fourth tune in the collection is named Ealing School. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The first and third couples meet and pass under each others arms, while the second couple set back to back ----- the first and third meet again, and pass to their own places, the first couple casting off one couple ----- the Gentleman right hands across at bottom and left at top, while the Lady right hands across at top and left at bottom :::::

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 16 bars of music in common time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

The first and third couples meet and pass under each others arms, while the second couple set back to back; the first and third meet again, and pass to their own places, the first couple casting off one couple

This is the first figure we've seen for which we lack a description from Wilson. It's an unusual figure in which the top and bottom couples within a minor set interact while the middle couple do something else. This concept isn't entirely unknown amongst Wilson's works, his The First and Third Couple Meet in the Center, Foot, and Return to their Places is conceptually somewhat similar. McFarren's figure is notable for having the middle couple set while the top and bottom couples are active; most country dances at this date were arranged for the pleasure of the first couple, it's unusual to find non-essential activity assigned for any other couple.

I suggest that the first and third couples advance to meet each other and the first couple pass under the arms of the third couple in order to swap places; meanwhile the second couple face away from each other and set facing outwards from the dance. Then first and third couples advance again, the third couple pass under the arms of the first couple and the first couple then cast into second place while the second couple move up.

|

B 1-8 |

|

the Gentleman right hands across at bottom and left at top, while the Lady right hands across at top and left at bottom

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The leading couple who are now in progressed places separate, the man dances a hands-three figure at the bottom with the third couple while the lady does the same at the top with the second couple; then the man dances a hands-three at the top with the second couple while the lady does the same at the bottom with the third couple.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance features a figure that isn't known from the Wilsonian repertoire but it is broadly consistent with Wilsonian principles for how a Country Dance should be arranged.

Mrs Aylmer of Perth's Reel

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The fifth tune in the collection is named Mrs Aylmer of Perth's Reel. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Swing hands and cast off one couple ::::: ditto and cast off another couple ::::: lead up to the top, cast off and allemande ..... set cross corners ..... hey on your own sides .....

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 32 bars of music in common time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-8 |

|

Swing hands and cast off one couple, ditto and cast off another couple

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The leading couple right hand turn once around and then cast off as the second couple move up; they then right hand turn a second time and cast off below the third couple (who do not need to move up, though they can do so if they wish).

|

B1 1-4 |

|

lead up to the top, cast off

Wilson did not document this figure exactly, though it is similar to his Lead Through the Top Couple except that our figure starts below the third couple rather than from the second couple's position.

The leading couple have four bars in which to lead up the set and cast into middle position.

|

B2 1-4 |

|

allemande

This figure known as the allemande is a little complicated, not least because it evolved in meaning over time. Thomas Wilson explained what he meant by the term allemande , his meaning was equivalent to a dos a dos figure; ordinarily I would interpret most allemande figures in a Wilsonian style at our 1808 date, except that I note that McFarren featured a figure named allemande dos a dos in his The What d'ye call it? (see below), a term that seems to match that used by Wilson. I therefore suspect that the allemande in this dance is something else, presumably the interlocking arms figure of the later 18th century.

We've written another paper of the Allemande figure, you might like to follow the link to read more.

|

AA 1-8 |

|

set cross corners

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram) under the name Set Contrary Corners. Wilson introduced a new repertoire of fancy figures in the 1811 second edition of his Analysis of Country Dancing, it included a figure that Wilson named Cross Corners. An argument could be made for using that figure in this dance, it seems improbable that this is what McFarren had in mind however, it's more likely that the regular Set Contrary Corners was intended.

The leading couple (who begin the figure from progressed positions) move to their right corner and set; they then turn away and move to their left corner passing their partner by right shoulders on the way; they then set to their left corner and return back to middle positions.

|

B 1-8 |

|

hey on your own sides

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The leading couple (who begin the figure from progressed positions) and the third couple turn to face the topmost couple, the top couple turn to face the leading couple. The men weave between each other, the ladies do the same thing on their side of the set. Dancers might like to dance a mirror-hey where the weaving pattern turns in at each end and bulges outwards in the middle. It's a difficult figure to explain, it might be easier to visualise by watching the animation.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance has been arranged in broadly Wilsonian terms though a non-Wilsonian allemande figure has been suggested.

Princess or No Princess

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The sixth tune in the collection is named Princess or No Princess. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The title appears to reference a stage production by Dibdin named The Forest of Hermanstadt, or Princess or No Princess that was performed at Drury Lane in October 1808. The music may have been derived from or influenced by the stage production.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The first, second and third couples advance to opposite places, the Ladies passing under the Gentlemens' arms ----- ditto return to their places, the Gentlemen passing under ----- lead down two couple, double promenade up the middle, and cast off :::::

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 16 bars of music in 6/8 measure.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

The first, second and third couples advance to opposite places, the Ladies passing under the Gentlemens' arms, ditto return to their places, the Gentlemen passing under

This figure wasn't precisely described by Wilson though it's very similar to his All the Ladies and Gentlemen Lead Through figure. McFarren's figure has the Gentlemen making arches for the ladies to pass under, presumably the first lady passing through the arch made by the first and second men; whereas Wilson makes no mention of arches and has the first lady pass above the first man.

|

B 1-8 |

|

lead down two couple, double promenade up the middle, and cast off

This is another figure in McFarren's collection for which it's difficult to find a Wilsonian precedent. The leading is explicitly finished with a cast , something rarely seen in Wilson's dances and the lead up is a double promenade . It's not entirely clear what McFarren intended to be understood by a double promenade .

The instruction to lead down two couple is highly Wilsonian, except that Wilson expected the leading couple to go down for the distance of two couples and then return one space back up.

I suggest that the leading couple lead down two spaces while the second and third couples both progress up a space (in half the music). Then the third couple promenade up the middle followed by the leading couple, they cast behind the second couple (who are now at the top) and return back to third place; the leading couple cast behind the second couple to the middle.

Alternative arrangements are of course possible, readers might like to come up with their own arrangement of this figure.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is the least Wilsonian of the collection so far; it includes several figures unknown from Wilson's works.

Madame Deshayes's Hornpipe

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The seventh tune in the collection is named Madame Deshayes's Hornpipe. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The dedicatee was a principal dancer at the King's Theatre Italian Opera House (see also Figure 4, Wilson dedicated a book to her). The title implies that this tune was used by Madame Deshayes for a popular stage Hornpipe dance (perhaps similar to Mrs Wybrow's Hornpipe that we investigated in a previous paper). Whether or not she had actually performed to the tune is unknown.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The first couple lead through the second and third Ladies, the Gentleman casting down and the Lady up ----- then lead through the second and third Gentlemen; the Lady casting up and the Gentlemen down, ----- set three and three top and bottom ----- ditto sideways ----- six hands across and back again ::::: lead outsides

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 32 bars of music in 2/4 measure.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

The first couple lead through the second and third Ladies, the Gentleman casting down and the Lady up; then lead through the second and third Gentlemen, the Lady casting up and the Gentlemen down

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This figure is sometimes used as a substitute for a lead outsides figure (which also appears within this choreography). Wilson did describe this figure but he did so within the repertoire of new figures that he introduced in 1811, he named it The Lady Passes Round the Second Couple, and the Gentleman Round the Bottom. Wilson perhaps considered himself to be the inventor of this figure, if so then he was mistaken.

The first couple pass between the second and third lady, cast around them back into the centre, then lead between the second and third men and cast around them. The second couple should lead up whenever it is convenient to do so, the figure should end with everyone in two lines of three across the set. An argument could be made for returning the dancers to progressed positions at the end of this figure and moving back into lines at the start of the next figure; Wilson's figure leaves the dancers in lines of three and the following figure makes sense starting from that position so I suggest ending in lines across the set.

|

B 1-8 |

|

set three and three top and bottom; ditto sideways

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

Wilson envisaged this figure starting from progressed positions; in this particular dance it starts with the dancers already in lines across (unless the previous figure is extended to send the leading couple home of course).

The two lines of three set in around three bars of music then the leading couple move to the sides; the two lines of three at the sides then set to each other.

|

A 1-8 |

|

six hands across and back again

This figure has an unusual name which might imply something exotic. The more common figure is named Hands Six Round (where the six dancers join hands and circle once around), whereas this figure seems to be Hands Across figure but for six dancers rather than four. It's unclear whether McFarren intended a more common figure to be danced or not; given the precision with which he arranged most of his dances I'm inclined to take him literally. This figure is not therefore known from Wilson.

All six dancers should put their right hand in to the centre and dance a hands across figure, then return with their left hands in the centre.

|

B 1-8 |

|

lead outsides

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The figure that Wilson described as Lead Outsides is quite difficult to interpret, his descriptions of the figure are less clear than might be hoped for. It's not at all certain that McFarren would have shared Wilson's understanding of the figure. We have discussed the Lead Outsides figure before in relation to the dances published by the Cahusac family here.

I interpret the figure as involving the leading couple galloping out through the men's side of the set and setting to each other; then galloping out through the ladies side of the set and returning to the centre, then two-hand turning back home. It's an asymmetric figure, something that Wilson himself disapproved of. Whether McFarren would have intended the same figure to be danced as Wilson used under this name is uncertain, it's certainly possible though far from certain.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is somewhat Wilsonian in character, at least as we've interpreted it, but it's not entirely consistent with Wilson's system of country dancing. The six hands across figure in particular isn't hinted at within Wilson's works.

The What d'ye call it?

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The eigth tune in the collection is named The What d'ye call it. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The title of this tune appears to be a joke; one can imagine a Master of Ceremonies asking the leading couple "What tune?" and being returned as answer "What d'ye call it?", hilarity would be intended. It's perhaps a joke best suited to school boys.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Change sides ::::: back again ::::: lead down the middle, up again and cast off ::::: allemande dos a dos :::::

This dance is a duple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 16 bars of music in 9/8 measure. The original score does not show repeat markers around the strains, I've taken the liberty of adding them in; without repeats the tune would be played twice through from start to end. As the first figure involves two repeated parts it makes more sense to repeat the A strain for that figure and the B for the final figures.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-8 |

|

Change sides, back again

A figure named Set and Change Sides was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The Wilsonian Change Sides figure includes an explicit setting movement, something not mentioned by McFarren. Setting makes sense in this figure, there might be too little movement to fill the time otherwise; it remains possible of course that McFarren had some other figure in mind. The most likely alternative involves the ladies and gentlemen passing each other into opposite places, a figure McFarren described within The Lady's Choice (above) as The two Ladies lead through the two Gentlemen, who pass into the Ladies' places; then the Gentlemen lead through and the Ladies pass into their places . It therefore seems likely that McFarren did intend the Wilsonian figure to be used in this dance.

The top two couples turn to face their neighbours, the men facing each other and the ladies facing each other; all Set for two bars, then the ladies join hands and gallop across into the men's places in two bars while the men slip sideways into the ladies places, the ladies passing between the men. The figure is then repeated. Wilson's description of the figure has the ladies pass between then men in both halves of the figure, an alternative arrangement would be to have the men passing between the ladies on the return movement.

|

B 1-4 |

|

lead down the middle, up again and cast off

A figure named Lead Down the Middle was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here, a figure named Cast Off One Couple was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

Wilson very rarely featured the compound figure of lead down the middle, up again and cast off in his dances of the early 19th century, where he did he used it in a form that is liable to surprise most modern dancers. In Wilson's system a leading figure was often a sideways galloping movement and a cast was similarly a sideways movement (something perhaps similar to a chasse croise figure from French Country Dancing). It's possible that McFarren intended this style of leading to be used, but perhaps more likely that an 18th century style of forward facing leading figure was intended. It's notable that McFarren has choreographed this long lead-with-cast in the dance but arranged it to a half strain of music, this places a dependency on the music being played relatively slowly.

I suggest that the first couple join inside hands and dance down the set, turn to face back up the set, lead back to the top and separate to go around the second couple (who progress upwards into the first couple's original places) and end progressed in the second couple's places.

|

B 1-4 |

|

allemande dos a dos

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

McFarren has given this figure an unusual compound name. He previously used allemande without the dos a dos suffix in Mrs Aylmer of Perth's Reel above, it's likely that something different was intended in this dance. Wilson, in his various books, described the country dancing Allemande figure as being a dos-a-dos figure, one in which dancers move round each other's situation back to back with no hint of the complex intertwining of arms found in older allemande figures. It therefore seems likely that McFarren explicitly intended this style of allemande be danced. We've written more on the Allemande figure in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is highly Wilsonian in style, except that the leading figure is one almost never found in a Wilsonian dance. One could nonetheless interpret that leading figure following Wilson's suggestions, I've elected not to do so on the basis that I don't think Wilson's casting figure was widely known in the early 19th century... I could of course be mistaken. McFarren's Allemande figure seems to explicitly use the figure that Wilson taught under that name, it's good evidence that Wilson's allemande was widely known in 1808.

Follow her close

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The ninth tune in the collection is named Follow Her Close. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. It's not clear to me what the title refers to; one might have predicted that a chasing figure would be included in this dance but that is not the case.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

The first Lady goes between the second and third Gentlemen, while the first Gentleman goes between the second and third Ladies, and set back to back ----- turn and set face to face --- half figure at the bottom ----- ditto at top ----- Pousette :::::

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 24 bars of music in 6/8 measure.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

The first Lady goes between the second and third Gentlemen, while the first Gentleman goes between the second and third Ladies, and set back to back; turn and set face to face

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

McFarren gave this figure a different name to Wilson but it's evidently the same figure. Wilson's description of the figure makes it clear that all six dancers in the minor set should set back to back at the same time, something that isn't evident from McFarren's text alone. Wilson's figure leaves the leading couple improper at the end of the figure (something that is also implied in McFarren's text), this makes the rest of the dance awkward as as there's no obvious opportunity for the leading couple to swap sides, I therefore suggest that the leading couple return to their proper sides at the end of this figure.

I suggest that in the first two bars of music the second couple move up to the top positions and face outwards, the first couple cross down into the second couple's places, and the third couple turn away from each other leaving lines of three facing out of the set. In the next two bars all six set, and in the following two bars all six turn to face back inwards. In the final two bars the second and third couples set while the leading couple does a half two-hand turn back to progressed places.

|

B 1-8 |

|

half figure at the bottom, ditto at top

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

Wilson described several ways to dance a Half Figure that varied only in the starting position and the direction of movement; curiously he seems not to have described this specific variant though it was within his repertoire. The first half figure involves the leading couple crossing down through the third couple and returning to their partner's starting position; then the second half figure sees them crossing up through the second couple and returning the their progressed positions.

|

A 1-8 |

|

Pousette

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This is the same figure that we saw in Princess Charlotte of Wales's Waltz above, the same comments apply here. Wilson went on to use the phrase Half Pousette to describe a single rotation of a pousette figure and Whole Pousette to describe a one-and-a-half rotation of a pousette figure. His early arrangements were less consistent however, Wilson's c.1809 country dance arrangements sometimes featured a Pousette of the same form used by McFarren here. That is, a single-rotation non-progressive pousette, something he would later refer to as a Half Pousette .

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is generally Wilsonian in form despite the inclusion of several minor anomalies compared to Wilson's encyclopedic works.

Ben the Sailor

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The tenth tune in the collection is named Ben the Sailor. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The name Ben the Sailor refers to a recurring character of the Georgian stage that originated in William Congreve's 1695 Love for Love, McFarren's tune is appropriately a hornpipe.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Promenade three couple ::::: cast off one couple and half figure at bottom ::::: the three Ladies hands round, while each Gentleman takes hold of the Lady's hand who stands next him ----- back again ----- the Lady hey at top and the Gentleman at bottom :::::

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 32 bars of music in common time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

Promenade three couple

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The Promenade is a fairly well documented figure, we've written about it in a previous paper. Three couples take promenade hold with their partners and then the leading couple cast off to the left, lead down and cast back up to their original places, followed by the second and third couples. Wilson mentioned in his text that at earlier dates it was common to dance the promenade figure with hands crossed behind the dancers' backs, whereas by his date the hands were generally crossed in front of the dancers.

|

A 1-8 |

|

cast off one couple and half figure at bottom

The Cast figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here, the Half Figure was described here (see also the diagram).

Wilson described how to dance both the cast and half figure figures, neither was described in the form I'd expect McFarren to have intended. We've discussed Wilson's Cast Off One Couple in The What d'ye call it (above) but we've seen McFarren use the word cast multiple times in dances where Wilson's figure would be inconvenient. I expect McFarren intended the more common interpretation of cast whereby the leading man three-quarter turns over his left shoulder and the leading lady does the same over her right shoulder, they move down into the second couple's position who in turn lead up to the positions previously occupied by the top couple.

We've discussed Wilson's half figure in Follow her close (above). Wilson seems not to have documented this figure starting from the middle position, it is however the same figure he documented at the top of the set simply transposed down one position. This half-figure has the unusual effect of leaving the leading couple improper (on the wrong side of the set) at the end of the figure. A case could be made for introducing a half two-hand turn to return the leading couple to their proper sides at this moment (the cast and half figure can easily be performed in 6 bars of music leaving 2 for a half turn). The leading couple will have to return to their proper sides at some point within the dance and this will be a little awkward wherever it occurs, but as the next figure requires the leading couple to arrive improper the return cannot occur just yet.

|

B 1-8 |

|

the three Ladies hands round, while each Gentleman takes hold of the Lady's hand who stands next him; back again

This figure is a little more exotic than most, it's not to be found amongst the figures documented by Wilson. The figure commences with the first couple improper in progressed positions. The phrase hands three usually implies three people forming a circle all holding each other's hands, that cannot be the case in this figure as each Gentleman is to take the hand of a lady, she must have one free with which to do so. I therefore suspect that this is a hands across variant; the three ladies put their right hand into the centre and the three men turn to face clockwise, each lady collects the nearest man and takes him around the circle with her. They then return with left hands in the middle and everyone ends the figure back where they started.

It would be possible to use this figure to return the first couple back to the proper side of the set prior to the next figure, it is a little awkward to do so however. I suggest that the leading couple remain improper.

|

B 1-8 |

|

the Lady hey at top and the Gentleman at bottom

Wilson described a similar figure named The Lady whole Figures round the bottom, and the Gentleman round the top couple here (see also the diagram). It's not a precise match as in our dance the leading couple start improper, thus the Lady is in the position that Wilson marked for the Gentleman, Wilson's figure only has the leading couple moving rather than all six dancers.

Wilson did describe several variants of the Hey or Reel figure but seems not to have covered this specific variant. A Hey is similar to a Whole Figure from the point of view of the leading couple, except that the other dancers are expected to simultaneously dance a figure of eight. It's a little complicated to explain the track, I would suggest watching the animation if in doubt.

To further complicate matters we have to get the leading couple back to the proper side of the set by the end of this figure, I therefore suggest that they change places as this figure ends.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is somewhat Wilsonian in form despite the use of an exotic figure not known from Wilson's publications.

Countess Craven's Waltz

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The eleventh tune in the collection is named Countess Craven's Waltz. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. Countess Craven (c.1785-1860) was born Louisa Brunton, she was an actress who had the good fortune to marry William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven in late 1807. The Sun newspaper for the 8th December 1807 wrote: It is with much pleasure we state, that this Lady is on the eve of presenting her hand to the Earl of Craven. Her conduct in private life has been so amiable in all respects, that we have no doubt she will support the character which she is going to assume with uniform propriety, and with virtues that will adorn her future rank. .

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Lead down one couple ::::: the Lady three hands round at top, and the Gentleman at bottom ::::: swing corners ..... lead through the bottom and cast up ::::: right hands across at top :::::

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 48 bars of music in triple time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

A 1-8 |

|

Lead down one couple

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

McFarren's figures call for a short leading figure with no cast, this would presumably be the Wilsonian lead. The leading couple dance down the set as far as the second couple, then return back to middle position as the second couple move up. This could be performed as a sideways gallop, but given the waltz rhythm of the tune it might be more convenient for the dancers to face in the direction of movement.

|

A 1-8 |

|

the Lady three hands round at top, and the Gentleman at bottom

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This is another Wilsonian figure. The leading couple begin the figure in progressed positions, the lady joins hands and circles around with the second couple (who are at the top) while the man joins hands with the third couple and circles around with them.

|

BB 1-16 |

|

swing corners

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

There are several ways that a swing corners figure could be danced, Wilson was consistent in requiring a specific figure. Wilson's figure involves the leading couple (who start the figure in progressed places) joining right hands to swing into each other's places (4 bars), then giving left hands to the person on their right corner and swing all the way around (4 bars); then giving right hands once again to their partner and swinging back to their original positions (4 bars), and left hands to their second corner to swing all the way around (4 bars). The figure ends with everyone in the same position they were in at the start of the figure.

|

C 1-8 |

|

lead through the bottom and cast up

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The leading couple begin this figure in progressed places, they lead down through the third couple and cast back to the middle positions. Wilson rarely used the word cast in this context but McFarren has repeatedly done so.

|

C 1-8 |

|

right hands across at top

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

Wilson's diagram shows this figure being danced at the bottom of the set but it's much the same at the top of the set. The four dancers join right hands with the person opposite, all four dance once around the circle back to the place from which they started the figure. Wilson commented that the first lady and the second man should always have their hands uppermost.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is highly Wilsonian in form, it might almost be one of his own dances.

Sawney the Scot

This is a transcription of McFarren's music for the dance.

|

The twelfth and final tune in the collection is named Sawney the Scot. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance here. The name Sawney was used throughout the 18th and 19th centuries to personify Scotsmen in a similar fashion to how John Bull might refer to an Englishman. The tune includes the dotted Scotch Snap Strathspey rhythm typical of Scottish themed music at this date.

The figures, as printed by McFarren, are:

Whole figure at top ..... lead down the middle and up again ::::: set to the top couple ::::: the Lady goes round the third couple and casts up, then crosses over and goes round the second couple into her place, the Gentleman following ..... turn corners .....

This dance is a triple minor , each iteration of the dance involves 32 bars of music in common time.

|

| Musical Strain | Diagram | Figures |

AA 1-8 |

|

Whole figure at top

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

The whole figure involves the leading couple crossing down through the second couple, casting up around them into their partner's original position, then crossing down through the second couple a second time, and casting up around them back into their own original positions.

|

B 1-8 |

|

lead down the middle and up again, set to the top couple

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This short leading figure is similar to that seen in The Dicky Box (above). Once again it involves a Wilsonian style of leading with no cast. The and up again suffix could be seen as an argument for returning the lead dancers back to the top of the set at the end of the figure, the subsequent figures require the lead couple to have progressed however. Wilson's description of the figure is clear; the dancers end the leading in progressed positions (after 4 bars) and then set to the top couple (for 4 bars).

|

AA 1-8 |

|

the Lady goes round the third couple and casts up, then crosses over and goes round the second couple into her place, the Gentleman following

This figure involves a chase , the gentleman following the lady as she winds around the set. Wilson described several chasing figures across his works but not this example.

The leading couple begin this figure in progressed places. I suggest that the leading lady casts down behind the third lady and crosses behind the third man, then cast up around the third man and across back into her starting position; she then casts up behind the second lady (who is at the top) across behind the second man (also at the top) casts down behind that man and cross back into her starting position again. Her partner follows her throughout this figure.

|

B 1-8 |

|

turn corners

This figure was described by Thomas Wilson in detail here (see also the diagram).

This figure is similar to a swing corners figure (as seen in Countess Craven's Waltz above). The leading couple pass each other with right shoulders then two-hand-turn the person at their right corner, pass each other again with right shoulders and two-hand-turn the person at their left corner. Once again there are several ways this figure could be danced, Wilson consistently promoted this particular arrangement.

|

The dance then continues from this progressed position. This dance is generally Wilsonian in form though it contains an exotic figure not known from Wilson's works.

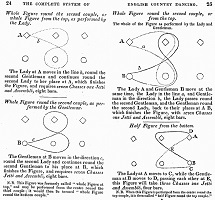

Comparing McFarren's Dances to Wilson's System of Country Dancing

We've now investigated McFarren's choreographed country dances from 1808. We can return to the question of how they compare to Thomas Wilson's system of country dancing at a similar date. We can immediately note that most of the dances are somewhat Wilsonian in form, both the terminology used and the figures employed are generally consistent with Wilsonian practice, so too are the relative timings of the figures. There are sufficient differences to confirm that McFarren was no pupil of Wilson however.

Figure 7. Example dances from Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore which share clear similarities with McFarren's dances

Of the forty-three figures encountered in the dances above (which may include a few duplicates) thirty-five were sufficiently similar to Wilsonian figures that we've associated a Wilsonian diagram with the figure. Of the remaining eight figures only five are unimagined in Wilson's texts, they are amongst the most complex of the figures within the collection. They are:

The first and third couples meet and pass under each others arms, while the second couple set back to back; the first and third meet again, and pass to their own places, the first couple casting off one couple (from Ealing School)lead down two couple, double promenade up the middle, and cast off (from Princess or No Princess)six hands across and back again (from Madame Deshayes's Hornpipe)the three Ladies hands round, while each Gentleman takes hold of the Lady's hand who stands next him; back again (from Ben the Sailor)the Lady goes round the third couple and casts up, then crosses over and goes round the second couple into her place, the Gentleman following (from Sawney the Scot)

These figures can't be dismissed as being entirely incompatible with Wilson's system of country dancing, they're simply obscure enough for him not to have commented on them. Wilson introduced an entirely new vocabulary of advanced country dancing figures in the 1811 edition of his An Analysis of Country Dancing, this later collection included figures of a similar complexity to the uncommon figures from McFarren's collection.

If we consider the key marker figures in Wilson's collection then they too offer a mixed picture. The most important of these figures is the progressive lead figure; McFarren arranged seven such figures, only one is non-Wilsonian in form (that being the long lead down the middle, up again and cast off figure in The What d'ye call it?), the remaining six are:

lead down the middle, up again (from The Dicky Box, a highly Wilsonian short figure)

lead down two couple and cast up one (from The Lady's Choice, a minor variation on a short Wilsonian figure)

lead up to the top, cast off (from Mrs Aylmer of Perth's Reel, a short figure beginning from an irregular starting position that logically follows from where the preceding Wilsonian figure ended)

lead down two couple, double promenade up the middle, and cast off (from Princess or No Princess, an exotic figure rarely seen elsewhere)

lead down one couple (from Countess Craven's Waltz, a highly Wilsonian short figure)

lead down the middle and up again, set to the top couple (from Sawney the Scot, a highly Wilsonian compound figure combining a short lead with a short suffix)

Most of the leading figures are Wilsonian in form. They are not restricted to only those leading figures that Wilson taught however, the inclusion of a long 18th century style of lead-and-cast demonstrates that McFarren was willing to mix both older and newer styles of country dancing within his collection. The long lead in The What d'ye call it? is a little peculiar in that it's arranged to a half measure of music, this could hint at an error in McFarren's printed notation, or more likely an expectation that the associated music would be played relatively slowly to provide sufficient time for the dancers to move the required distance. Wilson would occasionally arrange a long-lead-with-cast figure himself of course, especially in his early collections (see for example Lady Susan Hamilton in the bottom right of Figure 7), they would disappear from his arrangements over the next few years.