|

Paper 59

Dancing on Grass

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 17th September 2022]

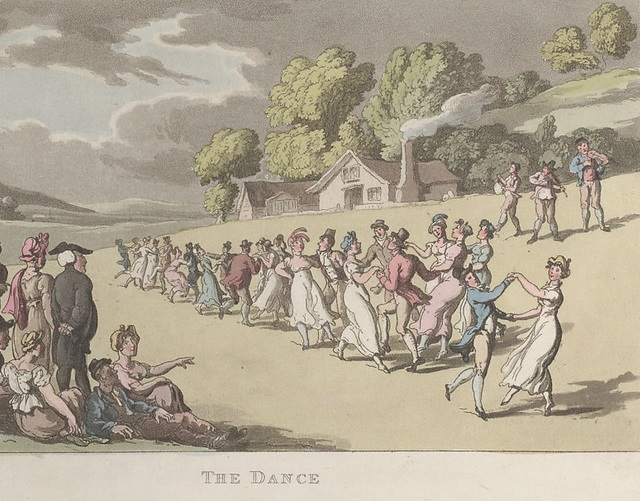

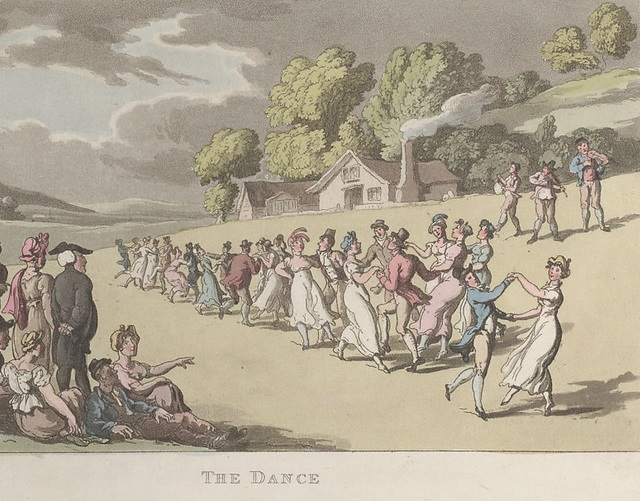

Someone asked me a little while ago about dancing on grass. Did people two hundred years ago dance outdoors on the grass? A number of historical images exist of people dancing country dances in a rural context (see, for example, Figure 1), the question was whether or not that was something that actually happened. I didn't have much of an answer at that time as most of the material I work with focusses on genteel dancing in the assembly and ball rooms. In this paper we'll attempt to discover what we can about outdoor dancing from the historical sources. We'll consider who was dancing outdoors, what they were dancing, and in what contexts they might do so.

Dancing in The Vicar of Wakefield

Figure 1. Rowlandson's 1817 illustration The Dance in The Vicar of Wakefield. Image courtesy of The MET.

Figure 1 is one of the twenty-four images created by Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) to illustrate the 1817 edition of Goldsmith's novel The Vicar of Wakefield. It clearly shows a longways set of couples dancing a Country Dance on grass, that picture was one of the inspirations for writing this paper. The novel itself was written by Oliver Goldsmith (1728-1774) between the years 1761 and 1762 and was first published in 1766, the plot of the book is set at an uncertain date presumably in the mid 18th Century. The passage that is represented in the image involves an episode where the Vicar, his family and a friend dine in a field. Shortly thereafter the local squire happens by with some friends and dancing is proposed, local villagers are attracted by the sounds of music and the dancing is (based on the image) enjoyed by all. Part of the passage reads (from Chapter 9):

The gentlemen returned with my neighbour Flamborough's rosy daughters, flaunting with red top-knots, but an unlucky circumstance was not adverted to; though the Miss Flamboroughs were reckoned the very best dancers in the parish, and understood the jig and the round-about to perfection; yet they were totally unacquainted with country dances. This at first discomposed us: however, after a little shoving and dragging, they at last went merrily on. Our music consisted of two fiddles, with a pipe and tabor. The moon shone bright, Mr Thornhill and my eldest daughter led up the ball, to the great delight of the spectators; for the neighbours hearing what was going forward, came flocking about us. My girl moved with so much grace and vivacity, that my wife could not avoid discovering the pride of her heart, by assuring me, that though the little chit did it so cleverly, all the steps were stolen from herself. The ladies of the town strove hard to be equally easy, but without success. They swam, sprawled, languished, and frisked; but all would not do: the gazers indeed owned that it was fine; but neighbour Flamborough observed, that Miss Livy's feet seemed as pat to the music as its echo. After the dance had continued about an hour, the two ladies, who were apprehensive of catching cold, moved to break up the ball.

There is much to comment upon in this brief passage, we'll discuss the additional details in the image shortly as they're also quite interesting. The text makes clear that the company were in a public outdoors location, a dance wasn't planned but came about by the addition of several additional parties in at least three distinct waves (the squire and his party, the Flamboroughs after invitation from the squire, then the rest of the neighbours). And yet, the dancing involved three musicians: two violinists and one with a pipe and tabor; this suggests that some degree of planning had been involved, or at least that the musicians had been sourced at the same time as the Miss Flamboroughs were invited to join in. Next we learn that the Miss Flamboroughs were reckoned the very best dancers in the parish and yet were totally unacquainted with country dances . The implication here is that the Country Dancing was a genteel occupation known to the Squire, the Vicar, and their entourages, but perhaps not to the inhabitants of this humble parish (except for the musicians, presumably local, who seem to have coped without comment). Or perhaps we should understand that the gentry were dancing Country Dances in a slightly different style or format to that of the villagers, a little shoving and dragging being all that was needed to get the dance started. I don't entirely know what to make of all that. Goldsmith implied that Country Dances were not part of the parish repertoire at the date at which the novel was set, the ladies could jig and dance the round-about to perfection (and no, I don't know what the round-about was, unless perhaps a general circle dance) but they were not proficient Country Dancers. The vicar's daughter was of course the star performer, the ladies of the town couldn't be compared to her. The dancing continued for about an hour before the party broke up.

Goldsmith's narrative is fiction so we shouldn't read too much into it. He wanted his readers to understand that his characters were coming down in the world, their genteel manners and priorities were not those of their new neighbours. Dancing was just one aspect of that, especially outdoor dancing. Genteel dancing required a prepared and solid surface; dancing on grass was something usually associated with the villages, townspeople would have Assembly Rooms or Long Rooms to dance at, perhaps even a Ball Room. Rowlandson's image, albeit fifty or so years after the book was first published, offers an idealised glimpse into what might have been normal for village dances when the story was set.

An aside discussing Rowlandson's image in Figure 1 The dance depicted in Figure 1 is deceptively fascinating. We've already mentioned that it is an inherently anachronistic image, created in 1817 to visualise a fictional dance that was written about in a book published in 1766. It represents a longways country dance and, at first glance, appears to involve a chaotic mass of unsynchronised dancers. It's a little more technical than that at closer inspection however.

Twelve couples are depicted in the dance at a moment when they're all dancing. If we assume that the top-most couple of the set are in the foreground, then that top-most couple is currently stood neutral (they're temporarily uninvolved in the dance). The three couples below them are dancing a hands six figure, the next couple are neutral, the next three are dancing hands six , the next couple are neutral and the final three are dancing hands six . It's an image of what we would refer to today as a triple minor , but with a neutral couple allocated between each minor set . We tend not to allocate neutral couples between minor sets in modern recreations of historical country dancing, it was something that the dance writers of the early 19th century wrote about however. Thomas Wilson was particularly vocal on the importance of allocating neutral couples between minor sets. This image offers some evidence that the convention was reasonably well known in the 1810s. Triple minor dances tend to be quite technical as the second and third couples in each minor set keep swapping positions as they progress up the dance; taking a turn stood-out as a neutral couple would allow a brief moment for dancers to reorientate themselves before being absorbed back into the dance. We might also notice that the neutral couple at the top of the set are actively dancing with each other, they're not stood to attention and waiting to be drawn back into the dance, they're clearly having fun together.

If we look at the rings of six dancers who are performing the hands six figures, we can see that at least two of them consist of two gentlemen dancing with four ladies, this indicates that some of our dancing couples were of the same gender. This isn't unexpected but it is interesting to see it depicted in an image. My impression is that Rowlandson had taken his own experience of country dancing of the early 19th century and used it to inform this picture of a fictional dance set fifty years earlier. He may have accidentally offered a unique insight into the dancing conventions of his own day in so doing. Whether or not this style of country dancing was also experienced back in the 1760s is uncertain; the written sources of the 1760s (of which there aren't many) don't refer to neutral couples being allocated between minor sets so I suspect it probably wasn't the norm back then.

Having considered a fictional account of outdoor dancing, lets turn our attention to some genuinely historical outdoor dancing. I've accumulated references to a number of such events, they've been grouped together into categories that we can study in turn below. The first of which is...

The Fête Champêtre

A Fête Champêtre was an elite form of entertainment designed to mimic the excesses of the French court at Versailles. The event would take place in a formal pleasure garden, a location in which might be found grottos, follies, grand landscaping, statues, mazes, water features, bandstands and so forth. Guests could promenade around the park discovering new scenes of wonder around each corner. Bands could be hidden so as to provide localised musical entertainment, a grand orchestra might provide ambient music across much of the park. Feasting would inevitably be part of the entertainment, perhaps in marquee tents erected for the purpose, so too dancing. A romanticised and serene rustic paradise was likely to be envisaged.

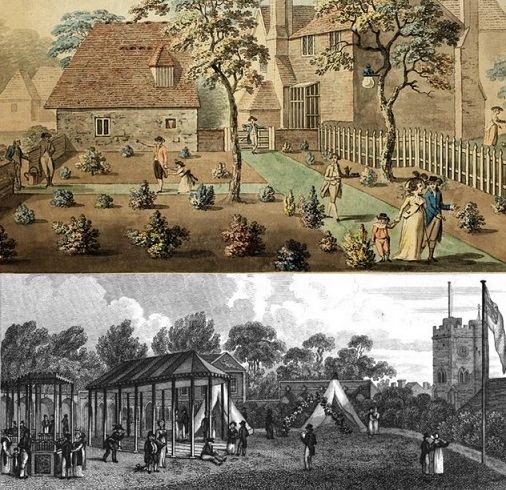

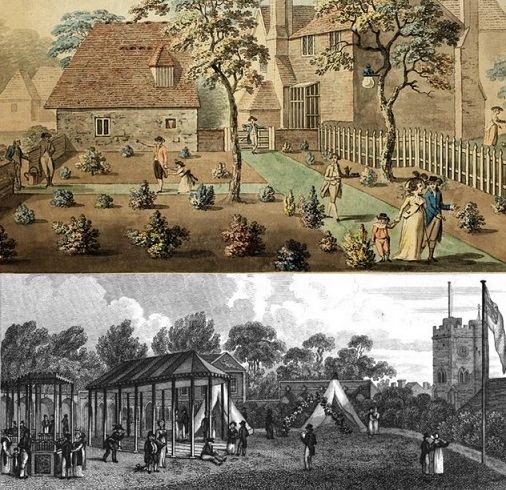

Figure 2. Artists impression of the Ball-room in the temporary Pavilion erected for Lord Stanley's Fête Champêtre, 1774 (above). Upper image dates from 1780, courtesy of the British Museum. Watercolour image of a Fête Champêtre, early 19th century (below). Lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Lord Stanley (1752-1824) hosted a Fête Champêtre in 1774 to celebrate his upcoming marriage to Lady Elizabeth Hamilton (1753-1797) at his home of The Oaks. The Morning Chronicle newspaper (11th of June 1774) wrote that it: was one of the most novel, elegant, and splendid festivals ever produced in this country ... it was beyond description grand and agreeable; its name was truly characteristic, as every fanciful rustic sport and game was introduced; there were groupes of Shepherds and Shepherdesses variously attired, who skipped about, kicking at the tambourines which were pendent from the trees, and an infinite number of persons habited as peasants who attended swings and other amusements, and occasionally formed parties quarices(?) to dance quadrilles. The day closed with dancing; the night opened with a display of a suite of grand rooms erected on the occasion ... . This event was evidently impressive. We're informed that the rustics (professional entertainers dressed as peasants) sometimes formed into groups to dance quadrilles, sadly the word preceding quadrille is difficult to read. These quadrille dances would probably be four person cotillion-like dances, not the Quadrille dances that would subsequently become popular a few decades later, we've written of them elsewhere. The Monthly Magazine in 1821 wrote more fulsomely of this same event, though they incorrectly recorded the date to have been in 1775; they described a formal masque entertainment on the lawn at 8pm, an orchestra having been hidden behind the orangery and professional performers entertained the guests. In the evening, and back indoors, the company danced minuets and cotillions, later country dances. There were Druidic ceremonies, cupids distributing flowers, singers, a dance by Sylvans ... and so forth. This event, more than any other, initiated the trend for hosting Fête Champêtres in Britain, it seems not to have featured much outdoor dancing however. Figure 2 shows an artist's impression, from 1780, of what the temporary pavilion erected for this event may have looked like.

Outdoor social dancing was attempted at some later events of a similar nature. It was reported of a Fête Champêtre hosted by Mr Walsh Porter in 1805 (Daily Advertiser, 6th of July 1805) that: Dancing on the Lawn commenced at nine o'clock, and in spite of the dampness of the evening, many a fair one tripped it lightly on the fantastic toe, till half past ten, when all returned to the house . Lord Clarendon hosted a Fête Champêtre at Clarendon Park in 1808 (The Star, 1st of September 1808) at which The amusements commenced with dancing on the green; the Duke of York's band playing. . The attendees at that event were a mixture of invited guests and the local populace who were allowed to watch. There was a challenge however: A temporary stop was put to the gaiety and harmony of the scene, by a cry of take care of your pockets. But fortunately, for the country Gentlemen and Farmers, Rivett, of Bow-street, and one of his coadjutors, made their appearance at the instant: then the heroes of the light fingered tribe, thought they could not do better than immediately decamp; which they did without ceremony. Order and personal security being restored, the dancing recommenced. . It was reported of an Irish Fête Champêtre hosted by Mrs Grady in 1822 (Saunders's News-Letter, 4th of June 1822) that A military band attended, and dancing on the grass continued till a late hour . In all three of these early 19th century examples social dancing for the privileged guests took place on grass. That surface was variously described as being a Lawn , Green or simply Grass , it may have been a well cared for and level lawn rather than a rough grassed surface. Dancing on grass, at least in this context, evoked the polished naive simplicity of an elite rural Arcadian gathering. It added to the spirit of the event, even if the dancers might have to avoid the more graceful stepping that was associated with the chalked floors of a ballroom.

Aside: on a vaguely related note, the historical origins of the term Country Dance may be linked to older events of this type. The authentic roots of country dancing are lost in antiquity, thus speculation is required. Country dances have existed in a published form from as early as 1651 but the format is known to be somewhat older than that. They are indisputably of British (probably English) origin. The oldest references to country dancing involve a genteel context and the oldest dances appear choreographed (created by a dancing master). My good friend and dance historian Barbara Segal has suggested that the first country dances may have been choreographed for professional dancers to perform, while dressed as rustics, at elite entertainments of a similar nature to the Fête Champêtre. These performance dances may have become so popular that the nobility and gentry chose to dance them for their own entertainment rather than merely watching, taking the name Country Dance in reference to the dances being associated with a fictional countryside context. Once Country Dances were published by Playford in the mid 17th century they circulated more widely, eventually reaching the villages themselves. This theory could explain why Goldsmith's fictional village dancers in The Vicar of Wakefield (as discussed above) had to be taught how to dance Country Dances, the elite form of dancing not having reached the vicar's village by the unknown date at which the story is set.

The Breakfast or Dejeunê

Hosting a breakfast was another variety of elite entertainment, only with much less effort and expense involved than at a Fête Champêtre. It was essentially an outdoor meal with light entertainment provided. It may be held in a public space or in a private garden, many people would be invited and both music and dancing were likely to be involved. The word breakfast didn't necessarily imply an early morning activity however, it was more an indication of a daylight and probably outdoors event, weather permitting.

Figure 3. A View from the Cascade Terrace at Chiswick House Gardens (above). Upper image © English Heritage Photo Library, via Old House Photo Gallery. Dancers in the garden of a country house, 1799 (below), lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

As an example, consider the following gathering held by the Duchess of Devonshire (1752-1806) in 1802 (The Sun, 28th of June 1802) at Chiswick House Gardens (see Figure 3): The Dutchess of Devonshire's breakfast at Chiswick, on Saturday last, was one of the most delightful entertainments of the kind ever given. The garden was not injured by any fantastic decorations, but left to its own natural beauty. Tents were placed in the most commodious situations, and the company were gratified with every thing a liberal Hospitality could provide. Though nominally a Breakfast, the repast consisted of a splendid collation, calculated to anticipate every want. The Company began to assemble about three o'clock, and visitors incessantly poured in from that hour till five. Musicians were stationed in various places, and the effect was animating in the highest degree. Many of the company danced upon the lawn, and the whole scene was truly Arcadian. The Prince of Wales did not arrive till near eight o'clock. The company consisted of the first persons of Fashion and Foreign Noblesse. More Beauty and Elegance were never observable upon a similar occasion, and the company separated highly delighted with the elegant and hospitable entertainment which the fineness of the weather enabled them so happily to enjoy. . The dancing at this event seems to have been informal.

A similar entertainment was held by the Duchess of Marlborough (1743-1811) in 1804. The Morning Post newspaper for the 23rd of June 1804 wrote: Duchess of Marlborough's public breakfast took place at Sion Hill yesterday. The company began to arrive about two o'clock. Between that hour and four, the public road was covered with carriages of every description. About half after four the breakfast took place on the lawn and in the house. On the lawn were erected five elegant marquees; and in the house, all the lower apartments were appropriated to the entertainment, which was, in every respect, suitably elegant. ... About half after six dancing commenced on the lawn, when about a dozen couple stood up to the lively tune of Sir David Hunter Blair . Soon after eight o'clock carriages were ordered, and the company retired. The Duchess of Marlborough, and the beautiful Lady Amelia Spencer, her daughter, superintended the whole of the amusements. The company exceeded three hundred fashionables . On this occasion we know that the dancing was conducted on a lawn and that a popular country dancing tune was used, we've written of Sir David Hunter Blair elsewhere if you'd like to read more about it. We're told that about 12 couples danced, which is a small proportion of the 300 or so fashionables who were present, it's about what we'd expect if the dancing had been held indoors at a society ball. It's likely that the same type of people would have been dancing as at a ball, primarily those who were considered to be marriageable.

Several similar events were described in 1808. Mrs Robertson Thornton (Morning Chronicle, 1st of July 1808) hosted a grand Dejeunê at her house near Clapham , it was reported that A band of music played for a considerable length of time, during which the younger branches of the company danced upon the turf . The Countess of Dartmouth (The Sun, 22nd of June 1808) hosted a breakfast at Blackheath at which Dancing commenced on the lawn, where 100 couple led off the second dance, The Labyrinth. . The tune named is one that we have studied before. Having 100 couples dancing would be unusual, most ball rooms would struggle to accommodate that number. Countess Spencer hosted another such event at Wimbledon (Morning Herald, 4th of July 1808) at which Bands of music were stationed in different openings of the lawn, where Country Dances and Scotch Reels commenced about three o'clock, and continued till near seven, when the Company began to retire . Such events might often involve informal dancing on grass, several of these events explicitly involved the dancing of Country Dances, one even mentioned the dancing of Reels.

A story was reported in the Ipswich Journal newspaper in 1795 (19th of September 1795) involving a royal review of the troops at Weymouth, after which the King and his party rode to the North Gloucester camp, where they were joined by the Queen, Princesses, and attendants, and partook of a late breakfast at 12 o'clock, provided for the purpose. Every elegance was prepared, and every attention paid to the royal visitors. After breakfast the ladies danced on the green, till 3, when the royal family returned to Weymouth . The Morning Herald newspaper reported of a similar event held by Hon. Colonel Wyndham for the local nobility in 1819 (21st of July 1819), after a meal dancing commenced on the lawn, to the music of the admirable bands belonging to the 9th, 12th and 19th, the lance brigade .

The Public Breakfast

Our next event is essentially the same as the elite Breakfast , except that it was usually a commercial activity that anyone could pay to attend: a Public Breakfast . These events would be held at an outdoors venue such as a pleasure garden and anyone who could afford the ticket was welcome to be present. The company might be less exclusive that at a private event but the entertainments could be equally impressive.

Figure 4. A View of Dandelion Gardens, Margate, mid 18th Century (above), and the covered dance floor at the Thanet Ranelagh Gardens c.1820 (below). Upper image courtesy of The RISD Museum.

One such venue was the Dandelion Gardens near the fashionable spa town of Margate (see Figure 4). The Margate Guide of 1785 wrote of the gardens that There is a public Breakfast here every Wednesday during the Season; the Band of Music attends, and Cotillons and Country Dances are danced on the Green till two o'Clock . In this instance the green may have been a bowling green. The Kentish Weekly Post newspaper for the 24th of July 1798 added The gardens at Dandelion were most respectably attended on Wednesday last, and forty couple, under the new and very proper regulations of a Master of the Ceremonies, were dancing on the green at one time . The Kentish Weekly Post in 1801 (28th of July 1801) shared that Dandelion Gardens, near Margate, were on Wednesday attended by a numerous and splendid company; not less than 20 couple enjoyed the delightful exercise of dancing on the green carpet which Nature and Art have jointly spread in that singularly pleasant part of the island; a marque in the gardens afforded ice-creams, jellies and every other refreshment in season . These later references aren't specifically to breakfasts but were held on Wednesdays, the day that the public breakfast is understood to have been held. The Morning Post newspaper in 1809 (30th of September) wrote of an unfortunate experience at Dandelion, many people had arrived for an advertised public breakfast there which the organisers had postponed due to bad weather; their hopes of an exhilarating dance on the green were disappointed and many of the people were drenched later in the day: Sorry are we to add, that those thin muslin beauties exhibited, on their return, the most distressed appearance imaginable . An 1818 reference to what was probably the same venue (Morning Post, 28th of September 1818) mentioned of a location near Margate that The gardens are open every day for public breakfasts, and dancing on the lawn. They have been well attended this season . The Dandelion gardens also hosted cricket matches and races, it was evidently a popular venue. A new and competing venue of Thanet Ranelagh Gardens was mentioned in the 1820 Picture of Margate, it boasted a platform for dancing fifty-five feet in length and eighteen feet in breadth, with a neat canopy over it. On the public days (Wednesdays) there is an excellent concert of vocal and instrumental music, and afterwards a ball and public breakfast. . This new venue offered a covered outdoor dance floor (see Figure 4), I can't say how popular it was but it may have been an attractive option. Dandelion evidently offered an elite style of dancing over several decades, albeit on the green; there was a Master of the Ceremonies allocated and both Country Dances and Cotillions are claimed to have been danced there in the open air, weather permitting.

Dandelion wasn't the only such venue to host dancing on the grass, or potentially under canvas. The Courier newspaper in 1806 (20th of August) recorded that A very elegant public breakfast was given on Monday last at Salt Hill, near Windsor. On the lawn were erected several marquees. The company exceeded 200 fashionables, principally consisting of the neighbouring Nobility and Gentry. Dancing commenced about three o'clock, when about twelve couple stood up to the lively tune of I'll go no more to yon Town. The breakfast commenced at four o'clock, and about half past five the party broke up . The named tune of I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon Town is one that we've studied before, it was the Prince of Wales's favourite dancing tune. It's unclear whether the dancing at this event was performed on grass or not.

Events of this nature might perhaps be associated with a race meeting. A Miss Stokes hosted an event that might have been described as a Breakfast for the Newgate Races in 1808 (Gloucester Journal, 1st of August 1808): Soon after dinner, the gentlemen were summoned to attend the ladies at the Villa, when dancing commenced on the Lawn, to the charming music of a Pandean band, stationed in the Conservatory. Three military bands, placed in various parts of the pleasure grounds, played martial music. Ices, and a profusion of the choicest fruits, were served to the company, who departed at a Late hour, charmed with the urbanity of their lovely hostess .

Fetes and other similar events

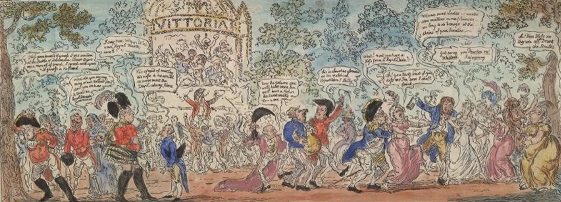

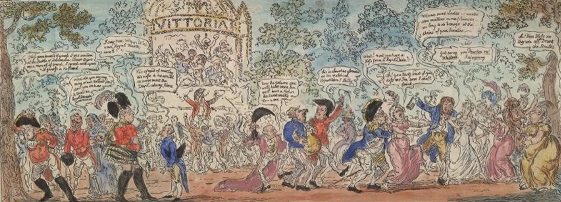

A medley of events described as fetes or similar also involved outdoor dancing. Figure 5 depicts a Fete held at Vauxhall Gardens in London which appears to show dancing on the bare earth.

Figure 5. Vauxhall Fete celebrating victory at the 1813 Battle of Vitoria. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Morning Post newspaper in 1806 (8th of October 1808) reported on the dancing that was expected to have been experienced at Mr Hannam's fete, if not for the rain; it: was to have consisted of a great variety of amusements, such as pigeon shooting, a pony race, a public breakfast, and dancing on the lawn; and in the evening, a dinner, ball, and supper, in the house. Owing to the extreme inclemency of the weather during the day, the rain descending in one continual torrent, all the first-mentioned amusements were abandoned. . Once again the rain interrupted the plans. Whereas an event near Southampton that same year was reported on in the British Press newspaper for the 12th of August: Yesterday, a grand rural fete took place at Netley Abbey. The band of the 13th, from Winchester, and the 14th from Portsmouth, were engaged at the venerable ruins, where upwards of 300 of the most fashionable partook of a cold collation, on pic nics . Forty couple danced on the turf till a late hour, and broke up with extreme regret. The parties went, in general, by water, and returned in carriages. .

An elegant fete in the gipsey style was held in Epping forest in 1819 (Morning Advertiser, 2nd of September 1819) at which: The party, about 40 in number, assembled at the foot of Hog Hill, and partook of a cold collation, during which a band of music, previously stationed on the spot, played a variety of airs. After the repast, dancing commenced on the turf, with the Voulez vous Danse under the trees, decorated with garlands. Quadrilles succeeded the country dances, and the company did not separate until late in the evening. . We've investigated the named tune of Voulez Vous Danser Mademoiselle? in a previous paper. This 1819 event is curious for not only being in the gipsey style , whatever that meant, but also for featuring Quadrille dances in the open air in addition to the Country Dances.

Albinia, Countess of Buckinghamshire (d.1816) hosted a Venetian Fete in 1812 (The Pilot, 13th of July 1812), it was reported that: About five o'clock the country dances commenced on the lawn; upwards of twenty couple led off. . This particular event was very popular and well attended by the nobility, two of the Royal dukes and also the Bourbon dukes in exile were present, though probably not involved in the dancing. An event described as a fair was held by Princess Elizabeth in 1808 (Daily Advertiser, 12th of August 1808) for the Nobility and Gentry of Windsor at which The Bands of the Royal House Guards (Blues), and Staffordshire Militia, played the whole time, and the Young Ladies and Gentlemen had a dance on the lawn .

Another event described as a Marine Fete was held in Edinburgh in 1804 (Caledonian Mercury, 14th of July 1804): A entertainment of a novel nature, a kind of Marine Fete, took place on Monday evening, on the beach between Caroline Park and Granton. A number of tents were erected, and every refreshment that the season could afford provided. The company consisted of a select number of ladies and gentlemen, the latter chiefly military. Two bands of music attended, and dancing on the green was kept up with great spirit till a late hour. The fete concluded with some brilliant fire-works .

Noblesse Oblige and dancing of the people

The nobility and gentry may have primarily danced in high quality ballrooms, assembly rooms and similar, but the labouring poor were often expected to dance on grass. There are many records of events held by the land owners for their rural neighbours, or for their own domestic servants, where the dancing was held on grass. The idea of Noblesse Oblige, or the obligations of nobility, remained a traditional concept. For example James Farquharson came of age in 1805 inheriting property worth £30000 per year (The Chronicle, 19th of October 1805), amongst the many entertainments at his celebrations the labouring people, and the poor of each parish, sat down to a sumptuous entertainment of roast beef and plumb-pudding, when the Dorsetshire ale soon set them all in motion; and being provided with good fiddles, they kept up the festive dance on the lawn, until a late hour . Mr Ralph Allen Daniell in 1809 (Royal Cornish Gazette, 28th of October 1809) entertained a select party of friends at his seat af Trelissick, in Feock, while a fat bullock, three sheep, and several barrels of strong beer; fed and rejoiced the spirits of the labouring poor of the neighbourhood and their families; of whom the younger part, at intervals, danced upon the lawn; while the aged rekindled their loyalty and gratitude by liberal potations, loyal songs, and generous toasts to the long life of the King and their beneficent patron . A report in the Morning Post newspaper in 1811 (27th of May) offered: It having been known for several days past that Mr David Dundas was to resign the office of Commander-in-Chief, and that the Duke of York was to be appointed in his room, the Duchess gave an entertainment to her domestics and neighbours at Oatlands. They danced on the lawn, on the spot set apart for that purpose, near the grotto. After the dance, they were regaled with a supper . Back in 1797 the Norfolk Chronicle (6th of May 1797) reported of a Mayday celebration that Yesterday, Mrs Montague, according to annual custom, entertained the Sooty Tribe with plenty of roast beef, plumb pudding, and strong beer, and, after dinner, ordered them a shilling each. The Duchess of York stopped some time in her curricle opposite the house, to see the dance upon the lawn. The concourse of spectators was immense .

If a land owner was celebrating then it was considered appropriate to provide entertainment for the neighbouring poor, often by way of a dance on the lawn of their property.

Figure 6. Rural Happiness at Cavernac, 1821, a circle dance is depicted. Image courtesy of the The MET.

Prince William, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1776-1834) married his cousin Princess Mary (1776-1857) in 1816. The Oxford University and City Herald for the 10th of August 1816 reported that they hosted an entertainment for the whole of the inhabitants of the country in the vicinity of Bagshot . It continued: The cloth was laid for 1000 persons on the lawn near the mansion. An excellent dinner covered the temporary table, built for the occasion, consisting of roast beef and excellent plum pudding, and fine old ale. After the assemblage had taken their seats, the Royal Couple, arm in arm, walked around the table to view the enjoyment of their neighbours; who, with due respect were rising from their seats to pay their grateful homage of respect, but the Royal pair condescendingly insisted on their not disturbing themselves, as they wished to see them all comfortable and happy. The healths of the amiable pair were then drunk with enthusiasm, and fervent wishes expressed that long life and happiness might attend them. Several bands of music attended; and after dinner the lads and lasses turned out, and danced merrily on the lawn. The assemblage consisted of young and old of various degrees; one among the latter was a lady, 93 years of age, who came in a chaise some distance to pay her respects to the Duke and Duchess. She appeared highly gratified at having the honour of speaking to them; and their Royal Highnesses were marked in their attention to her. The entertainment was kept up till a late hour. .

Patriotic events were sometimes held too. The Earl of Coventry hosted an event in 1814 to celebrate the Birthday of the Prince Regent for the gratification of the neighbouring villagers assembled on this joyful occasion, to the number of a thousand persons. ... The evening finished with dancing on the lawn, and the [Earl's] family, with that condescending attention to their guests which ever marks their munificence and hospitality, most cordially joined the amusements . At Newark in 1809 an event was held marking the local population's attachment to the Sovereign (Morning Post, 1st of November 1809): Five hundred tickets of admission were given out; five hogsheads of ale completed this old English repast. His Majesty's health was drank with three times three, and the two bands of music which attended struck up God Save the King which was sung by the whole people present; old and young danced upon the green, in divided sets, until sunset, when they all retired peacefully to their respective homes . The Morning Herald in 1821 (30th of July 1821) reported of an event at Aston Clinton held by Viscount Lake to celebrate the Royal Coronation: An excellent dinner was given, at the Bell Inn, to upwards on 60 yeomanry, with some gentlemen who were happy to join in the loyal feelings of the day, and attended by an excellent band of music until the evening, when it was claimed by an equally numerous party of ladies, who were assembled to tea and dancing. The public houses of the village were opened to the tradesmen and their families. The following day was given up to rural sports; and, in the evening, upwards of 300 of the young people, and the old who were made young, kept up dancing on the lawn, at the Noble Viscount's, until a late hour .

School children might occasionally be invited to dance on grass too. The Ipswich Journal newspaper for the 11th of August 1798 reported on an event to celebrate the Birthday of Princess Amelia (1783-1810) at Windsor. It reported that On the lawn in front of Frogmore-house, the children belonging to her Majesty's school were assembled to dance; the spot, which formed a square, being enclosed with a railing covered with artificial flowers, the arches at each entrance being decorated in the same manner, had a pleasing effect. The children having staid about an hour, were dismissed, being previously regaled with roast beef and plumb pudding. . The Windsor and Eton Express in 1815 (10th of September 1815) wrote about the Queens visit to Virginia Water: A most delightful entertainment and characteristic condescension of Royalty was conferred on the young ladies of Miss Bird's boarding school . The school girls stumbled upon a royal party who happened to be in the park; her Majesty, with the greatest affability and condescension, for which the royal family is so transcendent, sent for the young ladies to approach the royal party, and, tendering a profusion of refreshments, kindly noticed each of the young ladies in conversation, greatly enhancing the pleasure by retaining the young and beautiful group some hours, during which the royal band played several tunes, and the ladies, to the number of fifteen couple, danced on the shaded lawn, displaying their accomplished and graceful figures, with uncovered heads, to the apparent great pleasure and marked approbation of her Majesty, the Princesses, and the other distinguished personages. Such a scene of courtesy, so unexpected by them and by their amiable guests, can only be remembered with exulting pleasure and grateful sensations, for such great and unexampled munificence from the illustrious royal party .

Public Gatherings

Impromptu dancing could be associated with any kind of informal gathering. J.B. Wildman held a gathering to celebrate being returned to parliament in 1818, the Kentish Weekly Post (17th of July 1818) wrote that After dinner, dancing commenced on the lawn of the bowling green . The Examiner newspaper in 1819 (2nd of August 1819) wrote of a meeting of the Taunton Reformers at which Several sensible addresses were made; many excellent toasts were given; the songs were pleasant and patriotic; the dancing on the turf was lively; and the day was spent altogether in a rational and agreeable manner . Way back in 1736 the Newcastle Courant newspaper (24th of April 1736) wrote of the celebrations following the passing of a bill in parliament related to the wearing of printed goods made of linen: the Night concluded with Dancing on the Green, by near 100 Women belonging to the Cotton-Printing, dress'd in printed Cottons, with Bonfires, and loud Huzza's. .

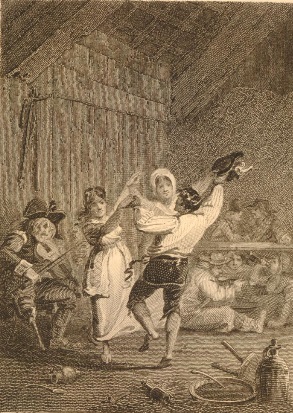

Figure 7. A rustic dance at an inn, date unknown. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

In 1776 the Hampshire Chronicle newspaper (29th of April 1776) reported that a large group of people assembled near Harnham from the surrounding villages expecting to see a military review. The expected Dragoons never materialised but booths were nonetheless set up to sell gingerbread and gin, instead of being displeased at the disappointment, it produced a contrary effect, for numbers of them formed into companies, and concluded the day with dancing on the Turf . Another story of military movements was shared in 1802 in the Lancaster Gazette (3rd of July 1802), a regiment was marching to Edinburgh and camped in the parish of Candy on the way; a local landowner entertained the officers with a cold collation, and the privates with ale and whiskey, on the lawn, where they danced reels with the country lasses; and an old woman, Maggie Hunnam, aged 90, was so elated with the sight, that she joined the dance with spirit . The officers on this occasion were entertained indoors and the rest of the soldiers were offered dances on the grass outside. General Wilder hosted a fete after a military review in 1814 (Morning Chronicle, 17th of August 1814), after dinner the parties broke up, and commenced dancing on the lawn, which was afterwards renewed with great spirit under the canvas, and kept up till past twelve. What added to the splendour of the scene was, the three fine bands of the Germans . Military reviews and their temporary encampments may have been an opportunity for a party across the country.

The Salisbury and Winchester Journal 1823 (23rd of June 1823) reported on an event held by the Waterloo Society in Ludgershall: After attending divine service, and hearing a most impressive sermon by the Rev. J. Webster, the members partook of an excellent dinner, served up by Mr Lansley, of the Crown Inn. After dinner the health of the Duke of Wellington, and his brave officers and men, were drank with three times three; the evening concluded with dancing on the lawn .

Village fetes

Local celebrations often involved dancing on grass, unfortunately they rarely got recorded in the press (with one important exception that we'll return to shortly). Some do occasionally get referenced however; for example it's recorded of the village of Dowsby in 1789 (Stamford Mercury, 8th of May 1789) that the whole parish turned out for a meal and There was a dance upon the green, wherein the people promiscuously joined . The same year it was recorded of the village of Swadlingcoat (Derby Mercury, 9th of April 1789) that an event was held to celebrate the Kings return to good health; After dinner many of the ladies and gentlemen formed a dance on the green turf, several upwards of eighty years old forgot their age, and danced with that alacrity which the happiness of the occasion inspired. On a similarly modest scale it was reported in 1802 (Morning Post, 24th of September 1802) that In consequence of the very abundant and plentiful crops, a Harvest Home was celebrated last week at Broomhall Farm, near Dorking, Surrey, the residence of Capt. Kent. The sports commenced at three o'clock in the afternoon, when ten beautiful young girls, about the age of twenty, started to run half a mile for a shift, after which another race took place by the above young girls for a cap. A third race also by five men sewed up in sacks. Dancing on the green and in the different barns adjoining to the farm continued till the hour of supper, at which fifty persons sat down. They afterwards danced till three o'clock the next morning .

Figure 8. Dancing around a Maypole, c.1741. Image courtesy of the V&A.

The Chester Chronicle newspaper for the 11th of June 1813 recorded another celebration, that of the Whitsuntide festival. It wrote: This annual holiday to the sons and daughters of labor, was this year celebrated with extraordinary festivities. The May Poles were decorated with more than usual taste, and the shreds and patches, which ornamented the garlands, seemed to shine, and flutter in the wind, with unequalled brilliancy. The devotees at the shrine of Bacchus were as numerous as they were devout; and the scrapers of catgut reaped no inconsiderable harvest in tuning their cremonas to the graceful movements of the rustic dance! On this auspicious day, other sports, of a more refined, although not less interesting nature, were not forgotten. The general joy was occasionally heightened by a most delightful dog-fight, and the aquatic amusement of duck-swimming ; and all those little delectable minutiae, which contribute to raise expectation and anxiety, were called in to wind up public gratification to the highest possible pitch. And though last not least, the ancient and honorable corporation of Juan, paraded the streets with the accustomed formalities; and if we may judge of the contents of his worship the mayor's cranium, by the size of his wig and the number of his tails, we should entertain a very high opinion of his sagacity . Although dancing on grass isn't specifically mentioned, dancing around a maypole was almost certain undertaken on grass (see Figure 8).

Such events of the people are fascinating to study today but were rarely commented upon in the newspapers 200 years ago. One important exception exists however, it pertains to the nationwide peace celebrations of 1814. We've written of the major London events of 1814 in a previous paper: the nation was celebrating the General Peace, the centenary of the Hanoverian dynasty and (perhaps) the expected nuptials of Princess Charlotte. It would transpire that the celebrations of peace were observed a little too soon (Napoleon returning from his exile to Elba in 1815), but in 1814 the celebrations were genuine. Villages across the nation held patriotic parties, dancing was often a part of that. For example, the village of Bramsfield (Ipswich Journal, 6th of August 1814) saw a merry dance on the lawn, in which all mingled, and which was kept up with the utmost order as well as spirit . At the Woolpit festival (Suffolk Chronicle, 30th of July 1814) dancing commenced on the lawn before the house, until the evening dews warned the company to retire to tea. The dancing was then resumed within doors, and kept up with spirit for the remainder of the day . At Leawood (Exeter Flying Post, 28th of July 1814) the village girls began the merry dance on the lawn, which continued a considerable time . At Oldcomb (The Star, 8th of July 1814) The evening's entertainment terminated with a rural dance on the lawn behind the parsonage ; at Froam (Bath Chronicle, 7th of July 1814) about forty couples danced on the lawn ; at Ditchingham (Norfolk Chronicle, 2nd of July 1814) the Lads and Lasses of the village struck up several country dances on the verdant lawn ; at Litcham (Norfolk Chronicle, 2nd of July 1814) A dance commenced early in the evening on the green, in which age and youth, rich and poor, eagerly joined, and harmony and happiness beamed in every face ; at Morton (Stamford Mercury, 15th of July 1814) the youthful part of the inhabitants commenced dancing on a green adjoining the river Trent and at East and West Wellow (Hampshire Chronicle, 18th of July 1814) the evening concluded with a dance on the Green .

Several of the village celebrations in 1814 triggered lengthy reports in local newspapers, we'll close out this paper with a more complete description of the celebrations at Kirby Underwood from the Stamford Mercury newspaper for the 22nd of July 1814:

Figure 9. Tom Jones dancing in a barn, 1811. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

The loyal inhabitants of this village have not been backwards in testifying their joy and gratitude on the happy return of peace. After a very liberal subscription had been raised (at the head of which stood the Rev. J. Goutch, Rector), Friday the 8th of July was set apart for the commencement of the festival. A barn belonging to Mr Hotchkin, 60 yards in length, stone-built and tiled, was cleaned and white-washed, and afterwards most tastefully and beautifully decorated with laurel and other evergreens, the sign of labor crowned, and with roses, ranunculuses, and almost all other sorts of choice flowers and shrubs, so as to have the appearance at proper intervals of four large Saxon arches - A pillar's shade High over-arched

The ends of the barn were very thickly interwoven with branches of our native oak, and looked like a living gallery of trees. The sides and space over both door-ways were very nicely ornamented with wreaths and festoons of flowers, and with new flags with the mottos Peace and Plenty, Peace and the Union, &c. Some large candlesticks, made for the occasion and covered with moss, were suspended from the roof, and when lighted had a peculiarly pleasing effect on the leaves and flowers - No wanton breezes toss'd the dancing leaves.

A stage was erected at one end for the band of music which had been ordered, and at the other end were placed three large barrels of prime ale, with casks of liquors, and sugar and lemons in abundance for making punch. Tables were prepared and cloth laid for the inhabitants; and at half past 2 o'clock a most plentiful and excellent hot dinner was served up, agreeably to the true old English taste - roast and boiled beef and plum puddings in abundance. The Rev J. Barwis presided, and the inhabitants of all ages sat down together (for there was no distinction of persons on this happy occasion), and after grace had been said all was equal and gladdened festivity, the band struck up God Save the King, and the barn looked like a royal cottage. The cloth being removed and thanks returned, good ale and punch went round in bumpers; and after the best of Kings, the village resounded with hearty cheers in honor of the Prince Regent, whose wise and firm policy with respect to the Peninsula, and in his choice of Ministers, laid the foundation for these splendid victories, that have not only immortalised the name of Wellington, but have so mainly contributed to the happy deliverance of Europe:- the Noble duke of Wellington, who had received the thanks of Parliament twelve different times (six more than the great Duke of Marlborough), Alexander, the King of Prussia, Old Blucher, Platoff, Miss Platoff, and Lord Castlereagh, the great pacificator of Europe . After these toasts had been drank, a procession took place round the village, with colors flying, bells ringing, and bands of music playing the White Cockade .

It was customary with the ancients to crown themselves with oak-leaves and flowers during their convivial entertainments; and this was done in full measure at Kirkby. An effigy of the fallen tyrant on his way to Hell-bay, and a person representing the famous old Blucher smoking his pipe accompanied the procession; and after having paraded the village, they returned to the gay barn, when the merry dance began. Several well-dressed females attended from other villages, and joined the motley group and rustic dance, both in the barn and on the green. The tables were furnished with punch and good ale, and pipes and tobacco. Some excellent songs were sung, accompanied by the violoncello; hilarity shone in every face; Johnny Bull, Mrs Bull, and their son Jackey, were all highly delighted together. A succession of loyal and local toasts continued to be given from the chair, and all expressed their approbation by loud cheering, the bass drum rolling and swelling the loud huzza!

The tea paraphernalia was brought into the barn, and plum cake and tea provided for all who chose to partake. Kissing all round began, and first with the worthy chairman and Mrs Hotchkin; whilst Mr H. good humouredly looked on, and loudly expressed his hope that much good would come of the Parson's salute! It may well be said, that Comus held his court here. Dancing commenced again with spirit and regularity, and all was pleasure and amity, with good order and decorum.

The memory of that illustrious character, the polestar of the State, was not forgot: a tribute was paid to his spotless and well-earned fame: his counsels saved the country, and if it had not pleased the Almighty to have spared that ever-to-be-lamented statesman's life till now, his wishes would have been complete. And if his spirit be allow'd to know / The mortal struggles of this world below, / Pitt will for England feel a guardian's care, / And all her sorrows, all her triumphs share; / For ere to death his parting sigh was given, / The Patriot cried, Oh, save my country, Heaven !

Love for the country, and the wish for its prosperity, are passions which never become extinct in generous hearts. The memory of our great naval hero was drank, with many other renowned characters. The merry dance was continued till bright Phoebus visited the barn. Morpheus also paid his visit, and some were found sleeping amongst the leaves and branches of oak. The wood's a house, the leaves a bed, and (Passing all belief) in strange array / A lovely damsel issu'd to the day.

Hilarity was raised to its highest pitch, and the greatest harmony and conviviality prevailed.

Plenty of the good things being left, the band of music paraded the village on Saturday, when the inhabitants assembled at the barn again, where the rustic dance and festive scene were re-commenced, and the amusements were kept up with spirit, until the sombre shades of night stopped the motions of the jocund train, when all parted, perfectly happy. The bread that was left was on Sunday morning distributed to the poorer families of the village. Mr Hotchkin officiated as Receiver-General and Paymaster on this happy occasion; he was the promoter and ample provider, and the utmost praise and thanks are due to him and his family, for their meritorious exertions in rendering every assistance, and in waiting upon all. Perhaps never were two days kept up in a village with more loyalty and festivity, and long will the celebration of the glorious peace of 1814 be remembered at Kirkby Underwood. All were unanimous, except the holder of the tithe-farm: he turned up his nose at the idea of rejoicing for peace, and would not contribute his company, nor any thing else, to such a meeting. The writer of this desires to inform him, there is a companion for him in Dunsby Fen. We know there are some who would give a torch to the sorrows of the country, and a rushlight to her triumphs:- but the spell is broken, Peace is concluded, with a Bourbon instead of Buonaparte! There be those who cannot rejoice at this event; it were too much to expect it! Suppose they take a trip to the Isle of Elba, to see their old favourite. They will find no rejoicings there: all will be as gloomy and miserable as they could wish.

The festivities at Kirkby Underwood were likely no different to anywhere else in the country. We gain an unusual insight into how a common village might hold a celebration, though the details of their dancing remain obscure.

Conclusion

Across this paper we've found countless casual and anecdotal references to dancing of the late 18th and early 19th centuries taking place on grass. This so called rustic dancing was primarily associated with the villages and the poor, but we've also seen elite and noble dancers performing on what were presumably manicured lawns. We've seen references to Country Dancing, Reels, Cotillions and Quadrilles being performed on grass; the grass in question potentially being well cared for bowling greens. We've also seen references to dancing in barns and on covered wooden podiums. We've also read how inclement weather could spoil a planned outdoor event. It's sufficient evidence to be confident in stating that yes, people two hundred or more years ago really did dance on grass when the occasion merited it. They may not have danced with the same repertoire of steps as would be used in the ball room, this is largely a matter of speculation however. If you have further information to share on this topic do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Figure 1. Rowlandson's 1817 illustration The Dance in The Vicar of Wakefield. Image courtesy of The MET.

Figure 1. Rowlandson's 1817 illustration The Dance in The Vicar of Wakefield. Image courtesy of The MET.

Figure 2. Artists impression of the Ball-room in the temporary Pavilion erected for Lord Stanley's Fête Champêtre, 1774 (above). Upper image dates from 1780, courtesy of the British Museum. Watercolour image of a Fête Champêtre, early 19th century (below). Lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 2. Artists impression of the Ball-room in the temporary Pavilion erected for Lord Stanley's Fête Champêtre, 1774 (above). Upper image dates from 1780, courtesy of the British Museum. Watercolour image of a Fête Champêtre, early 19th century (below). Lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. A View from the Cascade Terrace at Chiswick House Gardens (above). Upper image © English Heritage Photo Library, via Old House Photo Gallery. Dancers in the garden of a country house, 1799 (below), lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 3. A View from the Cascade Terrace at Chiswick House Gardens (above). Upper image © English Heritage Photo Library, via Old House Photo Gallery. Dancers in the garden of a country house, 1799 (below), lower image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 4. A View of Dandelion Gardens, Margate, mid 18th Century (above), and the covered dance floor at the Thanet Ranelagh Gardens c.1820 (below). Upper image courtesy of The RISD Museum.

Figure 4. A View of Dandelion Gardens, Margate, mid 18th Century (above), and the covered dance floor at the Thanet Ranelagh Gardens c.1820 (below). Upper image courtesy of The RISD Museum.

Figure 5. Vauxhall Fete celebrating victory at the 1813 Battle of Vitoria. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5. Vauxhall Fete celebrating victory at the 1813 Battle of Vitoria. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.