English Regency Dances, Costumes, Balls, Etiquette, Lessons and Music

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

| Return to Index |

|

Paper 50 A Selection of Balls from 1810Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 13th May 2021, Last Changed - 8th March 2022]We've investigated numerous historical balls in our previous research papers, this paper will continue that theme by reviewing a medley of balls hosted by the British elite in the year 1810; in each case we have a brief description of the dances that were enjoyed at the events, we'll investigate the dances and tunes that are named. Over the course of this paper we'll review eight different balls held in London and elsewhere. We've previously studied a pair of balls hosted by the socialite Mrs Beaumont in 1810, they were her balls of April 1810 and of May 1810. We'll see that some of the tunes danced at the Beaumont balls were also danced elsewhere that year; several of the other tunes we'll encounter in this paper have also been the subject of our previous research papers. The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

Figure 1. A View of Cliefden House from Maidenhead Bridge, c.1776 [pictured prior to the fire of 1795].

Figure 1. A View of Cliefden House from Maidenhead Bridge, c.1776 [pictured prior to the fire of 1795].

The Earl of Orkney's Ball, at Clifden HouseThe Morning Post newspaper for the 15th of January 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): Cliveden Hall in Buckinghamshire (see Figure 1) was the family seat of the Countesses of Orkney, it is situated perhaps 30 miles from central London (and 4 miles from Maidenhead). It had suffered significant damage from a fire in 1795; the Hereford Journal for the 27th May 1795 reported that a servantThe ball and supper given last week by Lord and Lady Orkney, at their seat near Maidenhead, were of the first description. The company exceeded 150 persons of rank and fashion. The preparations were truly magnificent in every respect. In consequence of the central part of the mansion (which was destroyed some years since by fire) not having been rebuilt, it became necessary to attach two noble wings of the building to each other; this was effected by means of a long triumphal arch or covered way, composed of frame-work, having entwined in it laurel and other evergreens, intersected by branches of furze-blossoms. This passage was illuminated by radiant arches of variegated lamps. The long line of perspective, was terminated by the British star, which appeared with a brilliancy unrivalled by any other ornament of a similar kind. All the apartments were superb; and as the furniture was classically elegant and modern, the chef d'ouvre was admirable. The company began arriving at ten o'clock, the dancing soon afterwards commenced withThe Fairy Dance,by Lord Orkney and the Hon. Miss Crawford Bruce. The Hon. Mr Macdonald followed, with Miss Scot Murray; two sets were formed of twenty couple in each. The second dance wasMorgiana;the latter was the favourite throughout the night. The spirit of the scene continuing throughout unabated, at half-past one in the morning the accomplished Peer ordered the supper to be delayed for another hour; it was nearly three o'clock before the dancers retired. In a very noble saloon the supper was set out; more taste and profusion were never seen displayed with a better effect; the ornaments in confectionery were beautiful. E'er the hour of four the dancing was renewed with Scots medlies and German waltzes. At six o'clock, the company being then almost quite exhausted with fatigue, the Earl and Countess entertained their guests with an Irish gig; which was performed with inimitable perfection, as to charm those who were competent judges of its merit, and convulse with laughter, others. The same dance was exhibited at the Duchess of Gordon's ball, in Piccadilly, about ten years since. The parties were Mr Quin and Lady Kier. All the neighbouring Gentry were at Clifden House, including Sir Joseph Mawbey, the Scott Murrays, Crawfurd Bruces, Smiths, and Thompsons. incautiously went to bed, leaving her candle burning by the bed-side, which caught the curtains, and the whole room was in a flame in a few minutes, and in a short time got to such a head as to defy all human prevention. The house being on such an elevated situation, the blaze, which was exceedingly tremendous and awful, was seen for many miles round.. We're informed that the hall was patched up for our ball of 1810, a fabulous arch of foliage and lamps was used to connect the two wings with a patriotic centre-piece in the form of a British Star. The guests were impressed.

The 4th Countess of Orkney was Mary FitzMaurice (1755-1831), her husband (the Earl) had died in 1793 and as the Orkney title was hers (suo jure) it's not entirely clear who the host of our ball actually was. I imagine it was hosted by her son John FitzMaurice, Viscount Kirkwall (1778-1820); if so, the referenced

The programme for the evening evidently involved a number of popular dances which we'll investigate further below. One interesting detail is that for the first country dance

Figure 2. Portman Square in London, pictured c.1810.

Figure 2. Portman Square in London, pictured c.1810.

Dowager Countess of Clonmell's Ball and SupperThe Morning Post newspaper for the 19th of March 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): The dowager countess of Clonmell in 1810 was Lady Margaret Scott (c.1763-1829), her husband had been John Scott, 1st Earl of Clonmell (1739-1798). She was a member of the Irish peerage who lived in London (at Portman Square, see Figure 2). She evidently chose the date of her ball to coincide with St Patrick's Day and had selected an appropriate tune to be danced in the early hours of the morning. We're not given many details of her ball beyond the typical pleasantries that might be used to describe any ball at this date. We have previously studied another ball held in London in 1801 by members of the Irish peerage, with a distinctly Irish theme, you might like to follow the link to read more of this type of event.On Friday night the Countess Dowager of Clonmell gave a grand Ball and Supper at her elegant mansion in Portman-square, which, in point of taste, elegance, and splendour, excelled any entertainment given this Season. The two beautiful front drawing-rooms were lighted up in the most tasteful and superb style, with brilliant chandeliers, lustres, Grecian lamps, and vases; the floors were elegantly chalked in emblematic designs by an eminent artist. At eleven o'clock dancing commenced, and at two o'clock an elegant supper, consisting of all the delicacies of the season, was served up on a superb service of plate. The dining-rooms were admirably well arranged and lighted up. Two hundred covers were laid. After supper, it then being St. Patrick's day, the merry dance was resumed, and led off by Lady Charlotte Scott and the Marquis of Downshire, to the favourite and much-admired tune ofPatrick's day in the Morning. Among the company were... The first dance after supper was led off by Lady Charlotte Scott (1787-1846), she was the countess' daughter; her partner for the dance was Arthur Hill, 3rd Marquess of Downshire (1788-1845). Hill was a highly eligible young bachelor, he was a prominent dancer at many of the balls we'll be studying of 1810. He went on to marry a daughter of the 5th Earl of Plymouth in 1811.

The Duchess of Dorset's Ball Figure 3. Grosvenor Square in London, pictured c.1810.

Figure 3. Grosvenor Square in London, pictured c.1810.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 23rd of March 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): The Duchess of Dorset (1767-1825) was the hostess for this ball the guests at which included the Prince of Wales and two of his brothers. Her husband the 3rd Duke of Dorset had died in 1799, their children included the 17 year old Lady Mary Sackville (1792-1864) who led off the first dance and the 16 year old George Sackville, 4th Duke of Dorset (1793-1815) who followed her. The ball was held as a formal introduction of Mary to polite society. The fantastic ornamental pastry on the head table was constructed in her honour, the Prince's personal confectioner had been employed in its construction. Mary would go on to marry Other Windsor, the 6th Earl of Plymouth in 1811. We're informed that the guests were so numerous that the carriages were often three-deep for as much as a quarter of a mile from Dorset House.Dorset House, in Grosvenor-place, was opened on Wednesday evening, for the first time. This mansion is of the most elegant description, and we shall take an early opportunity of describing its beauties. The dancing once again involved a variety of different styles, we'll investigate the dancing further below. One of the guests at the event was the Persian Ambassador, we'll hear more of him shortly.

The Duchess Dowager of Newcastle's Ball Figure 4. Berkeley Square in London, pictured c.1810.

Figure 4. Berkeley Square in London, pictured c.1810.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 4th of April 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): The Duchess Dowager of Newcastle in 1810 was Lady Anna Maria Craufurd (1760-1834), her first husband had been the 3rd Duke of Newcastle (1752-1795) but by the date of our ball she was remarried to General Sir Charles Gregan Craufurd (1763-1821). The ball acted as an introduction to society for her daughter Lady Charlotte Pelham-Clinton (c.1792-1811), Charlotte was a member of the party who danced a Reel in order to close the event. The Prince of Wales was present, as was one of his brothers, so too the Persian Ambassador (who was quite the celebrity this season).On Monday evening, at her Grace's residence in Charles street, Berkeley-square, far excelled every similar entertainment yet produced this season, if we except the very superb fete given lately by the Duchess of Dorset. The preparations at Newcastle House displayed the most refined taste, insomuch that the Prince of Wales was charmed by the uniform elegance which reigned throughout the whole. Ere eleven o'clock Berkeley-square was filled with elegant equipages; half an hour after 400 persons had gained admittance into the house. About the latter period the dancing commenced with a new reel, calledLady Madelina Sinclair. The Marquis of Downshire led off with Lady Charlotte Pelham Clinton, a most interesting and beautiful young Lady, having the advantages of being tall, and singularly elegant in her proportions. Lady Clinton is the daughter of the Duchess of Newcastle; it was her first introduction to the fashionable world, and on that account the ball was given. Among the couples who danced were the following:-

Lord Sydney's Ball and Supper Figure 5. Grosvenor Square in London, pictured c.1750.

Figure 5. Grosvenor Square in London, pictured c.1750.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 4th of May 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): This ball was hosted by John Townshend, 2nd Viscount Sydney (1764-1831), his first wife had died in 1795 and he remarried in 1802. His daughter from the first marriage was the Hon. Sophia Mary Townshend (c.1792-1852), she led off our ball with the 19 year old William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington (1790-1858) (he would inherit the title of 6th Duke of Devonshire in 1811); the ball may have acted as an introduction to society for Miss Townshend. We're informed that the first dance was so popular that it continued for around 90 minutes with 30 couples dancing!On Wednesday evening his Lordship gave a magnificent ball and supper, at his superb mansion in Grosvenor-square. The house was illuminated with wax candles only, placed in chrystal lamps. The ball was opened by the Marquis of Hartington, and the Hon. Miss Townshend, to the new tune of Morgiana in Ireland. Thirty couple went down the dance; it was so great a favourite that it lasted one hour and a half. Among the dancers were the following:- One unexpected couple reported to have danced consisted of the eligible Marquiss of Downshire and Lady Margaret Scott. Margaret Scott was presumably the Dowager Countess of Clonmell (hostess of one of our earlier balls). If that is correct then her presence in this dance is curious, it's more likely that her daughter Lady Charlotte Scott was the dancer and that our correspondent made a small mistake.

Figure 6. Kensington Palace in London, pictured c.1820.

Figure 6. Kensington Palace in London, pictured c.1820.

The Princess of Wales's Grand BallThe Morning Post newspaper for the 7th of May 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): On Friday evening her Royal Highness gave a Ball and Supper, at her apartments in Kensington Palace. The company invited were select; the principal drawing-room was fitted up for dancing; it was brilliantly illuminated by a single Grecian chandelier of the richest cut paste drops ever seen. The amusements commenced with the reel of Tulloch-goram, by the Duchess of Manchester, Hon. Mr St Leger, and the Hon. Capt. Warrender. Country dances ensued; Lord Hume was led off by Lord Ashbrooke and the Duchess of Manchester; followed by This ball was hosted by Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), the estranged wife of the Prince of Wales, at Kensington Palace (see Figure 6). We're not told much about the ball but the Duchess of Manchester (1774-1828) was evidently one of the more honoured of guests; the Duchess was similarly estranged from her husband (the 5th Duke) who had left the country in 1808 when appointed to the role of Governor of Jamaica. Perhaps the two ladies felt they had something in common.

The Countess of Shaftesbury's Ball Figure 7. Portland Place in London, pictured c.1815.

Figure 7. Portland Place in London, pictured c.1815.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 19th of May 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): Given on Thursday evening, at the magnificent mansion in Portland-place, is another proof of the great request in which such fetes are held this season. The capacious apartments, and there are four or five on each floor, were decorated with flowers and other fragrant shrubs; every room was illuminated by wax candles only. The Ball was opened at eleven withThe Persian Dance,by the Marquis of Hartington and Lady Barbara Ashley Cowper. About twenty couple followed, among whom were the following:- This ball was hosted by Barbara Ashley-Cooper the Countess of Shaftesbury, she married the 5th Earl of Shaftesbury in 1786. Their daughter was the 18 year old Lady Barbara Ashley-Cooper (1788-1844), the ball may have been held as her formal introduction to society; she led off the first dance with (once again) the 19 year old William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington (1790-1858). We'll investigating the dancing further below.

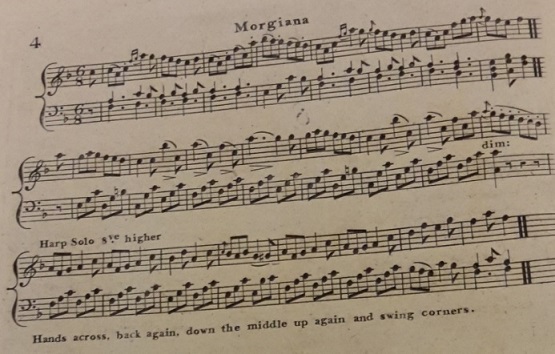

The Barfield Ball at Broadstairs Figure 8. A View of Broadstairs, pictured c.1828.

Figure 8. A View of Broadstairs, pictured c.1828.

The Morning Post newspaper for the 18th of September 1810 wrote (with dance references highlighted in bold): The Ball, last night, at Mr Barfield's small though elegant little Room, was crowded to excess, and was opened by the Hon. Miss Maynard, and Miss Henniker, to the delightful tune of...The Opera Hat, and followed by about 30 couple. It's not entirely clear who Mr Barfield the proprietor of this ball was but he evidently lived at Broadstairs on the Isle of Thanet in eastern Kent (see Figure 8). He may have been the owner of the local Assembly Rooms, his venue is described elsewhere as Barfield's Library. It's possible that this event was a public ball at which tickets could be purchased by anyone who wished to attend, or it may have been a private invitational event. The guests consisted of all the notables on the small island, notably Lord Henniker (1752-1821) and his family. Mr Barfield hosted a large company at his rooms with 30 couples dancing together. Many of the guests evidently went on to attended Lord Henniker's supper after this event ended.

One unusual observation involving this ball was that the opening dance was apparently led off by two ladies, this was contrary to the typical conventions followed at most of the nation's Assembly Rooms. Each Assembly Room would publish its own bylaws to govern such matters, an example issued by Edward Payne in 1814 directed: A mysterious foreigner and his partner impressed the locals in the Persian Dance. They are reported to have danced with the elegance of the leading stage performers of the London Opera House.

The Fairy Dance

... the dancing soon afterwards commenced with The Fairy Dance, by Lord Orkney and the Hon. Miss Crawford Bruce. The Hon. Mr Macdonald followed, with Miss Scot Murray; two sets were formed of twenty couple in each.(Earl of Orkney's Ball) We've studied the Fairy Dance (and investigated its disputed composition credit) in a previous research paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. It was a popular tune that had been introduced to society back in 1807, it was well known and widely danced at our date of 1810. We're informed that two sets of 20 couples danced to it at Lord Orkney's ball of 1810, they must have enjoyed it.

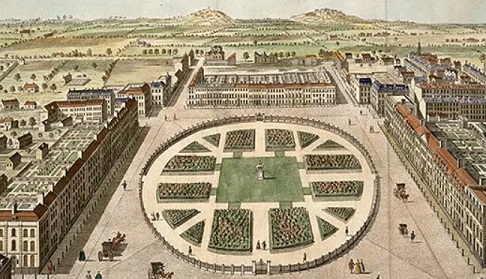

Morgiana (and Morgiana in Ireland) Figure 9. Morgiana from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 8th Number.

Figure 9. Morgiana from Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 8th Number.

The second dance was Morgiana; the latter was the favourite throughout the night.(Earl of Orkney's Ball) The ball was opened by the Marquis of Hartington, and the Hon. Miss Townshend, to the new tune of Morgiana in Ireland. Thirty couple went down the dance; it was so great a favourite that it lasted one hour and a half.(Lord Sydney's Ball and Supper) Morgiana is the name of a tune that became popular in London c.1808, it went on to inspire a family of related country dancing tunes including the c.1810 Morgiana in Ireland. We've studied Morgiana in Ireland before (together with the Morgiana tune that inspired it), you might like to follow this link to read more. We didn't investigate the publishing history of the initial Morgiana tune on that previous occasion so will do so now.

A precise chronology of publication for Morgiana can't be established but examples include: Campbell's c.1808 1st Number, Clementi & Co's c.1809 6th Number, Cahusac's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1809, Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 8th Number (see Figure 9), James Platts's c.1809 9th Number, Goulding's c.1809 14th Number, Button & Whitaker's c.1809 11th Number, Andrew's c.1809 19th Number, Monzani's c.1809 10th Number, Ball's c.1809 1st Number and Dale's c.1809 13th Number. It was also published in Bland & Weller's collection of 24 for 1810, Preston's 24 for 1810, Fentum's 24 for 1810 and in Davie's c.1810 20th Number (under the name We've animated a suggested arrangement of Skillern & Challoner's c.1809 version (see Figure 9) and of Button & Whitaker's c.1809 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Morgiana in England at The Traditional Tune Archive.

Scots Medlies, Reels and Strathspeys

E'er the hour of four the dancing was renewed with Scots medlies...(The Earl of Orkney's Ball) ... the third a Medley... The dancing recommenced at three o'clock, with reels and strathspeys(The Duchess of Dorset's Ball) A favourite reel, in which Hon. Captain Macdonald, Lady Pelham Clinton, Sir Robert Sinclair, and a Lady (unknown) joined, was given in the true Highland fling; the latter closed the night's amusements at six o'clock yesterday morning.(The Duchess Dowager of Newcastle's Ball) ... the evening's amusements concluded with reels and Strathspeys about seven in the morning.(Lord Sydney's Ball and Supper) Reels and strathspeys concluded the whole at eight o'clock.(The Countess of Shaftesbury's Ball)

Scottish themed dances were an important part of many London balls at this date, they were especially likely to feature towards the end of an event. We've investigated the confusion around the use of the terms The precise details of what was danced at our Balls is unknown, these dances were probably less formal than the preceding Country Dances and probably danced with greater vigour.

German Waltzes and Waltz Medleys

E'er the hour of four the dancing was renewed with Scots medlies and German waltzes.(The Earl of Orkney's Ball) The second dance was a Waltz Medley.(The Countess of Shaftesbury's Ball)

The couple waltz had been growing in popularity in Britain since the 1790s, especially so since the turn of the 19th century, we've investigated the phenomenon in a previous paper. A

Irish (and Scottish) Jigs Figure 10. A selection of Jigs. A Jig on Board, 1818 (top left); The Last Jig, 1818 (top right); Meg of Wapping, date unknown,

Figure 10. A selection of Jigs. A Jig on Board, 1818 (top left); The Last Jig, 1818 (top right); Meg of Wapping, date unknown, She'd shine at the Play & she'd Jig at the Ball(bottom left); A Tipperary Jig, 1818 (bottom middle); Hibernia in a Jig, 1801 (bottom right).

the Earl and Countess entertained their guests with an Irish gig; which was performed with inimitable perfection, as to charm those who were competent judges of its merit, and convulse with laughter, others. The same dance was exhibited at the Duchess of Gordon's ball, in Piccadilly, about ten years since. The parties were Mr Quin and Lady Kier.(The Earl of Orkney's Ball)

The Jig is a challenging dance to write about. It was widely referenced in the early 19th century both in the names of tunes and in vague references to dancing, rarely with any specificity. The dancing masters advertised tuition in the jig but they didn't write much on the subject, hence little is definitively known. The jig is therefore something of a mystery. Some modern authorities have attempted to reconstruct what dancers of the early 19th century would have understood by the word

One immediate observation is that the word

The 1766 edition of Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language defined the

The story doesn't end there however. Some dancing masters did teach a performance jig in the early 19th century. The most prominent among whom was Alexander Wills; he entered into partnership with Mr Second in 1801, they jointly advertised (The Courier, 5th December 1801) that: But how was a jig typically danced? Several caricature images of jig dancing do survive (see Figure 10), they are curiously consistent in the movements depicted. They generally depict either a solo or duo dance; the male partner will be shown with an arm in the air and the other hand at his hip, the female partner will have both hands at her hips or waist. Both partners will be shown performing complex step patterns with their feet. The dancers are evidently engaged in a performance. A trained dancer might have a fancy repertoire of steps to draw from but anyone could have a go at dancing a jig.

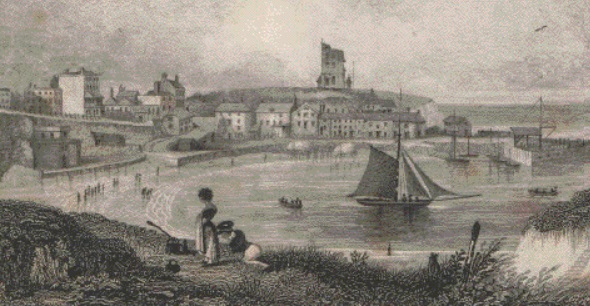

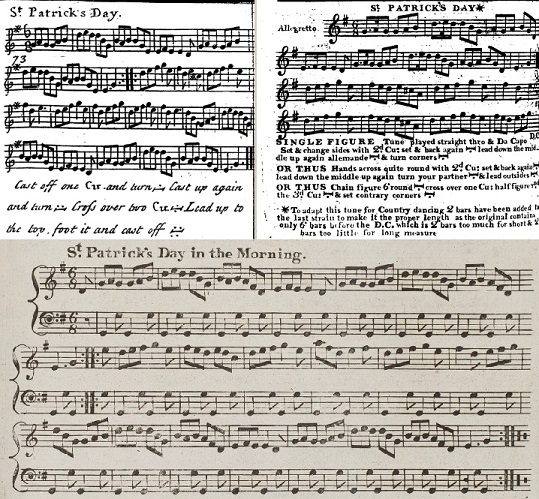

Patrick's Day in the Morning

After supper, it then being St. Patrick's day, the merry dance was resumed, and led off by Lady Charlotte Scott and the Marquis of Downshire, to the favourite and much-admired tune of Patrick's day in the Morning(Dowager Countess of Clonmell's Ball and Supper)  Figure 11. St Patrick's Day from Johnson's c.1740 A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (top left), from Wilson's 1816 A Companion to the Ballroom (top right), and from Dale's c.1809 15th Number (bottom).

Figure 11. St Patrick's Day from Johnson's c.1740 A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (top left), from Wilson's 1816 A Companion to the Ballroom (top right), and from Dale's c.1809 15th Number (bottom).

This tune had already been in circulation for at least seven decades at the date of our ball, it was supposedly of Irish origin although its roots are uncertain. The earliest publication of the tune that I can find was issued in London, it's the c.1740 first volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances (see Figure 11). It would also appear in the c.1756 first volume of Rutherford's Compleat Collection of 200 of the most celebrated Country Dances (it's the first dance in that collection). It would then be printed in the c.1759 12th volume of James Oswald's Caledonian Pocket Companion, once again in London. The tune reached further levels of popularity after being used by Thomas Arne in his 1762 opera Love in a Village to accompany a song named A plague of these Wenches; Arne identified the tune as being an

The first publication of the tune under the longer name of St Patrick's Day in the Morning may have been from Glasgow in James Aird's 1782 first volume of his A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs. It would then appear under the same name in Niel Gow's 1806 Part Third of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys & Dances where it was explicitly identified as being

Whatever the origins of the tune actually were, by our date of 1810 it was considered to be Irish. It was eminently suitable for an Irish themed ball held in London by a member of the Irish peerage. The tune had previously featured in a Dublin ball of 1802 (True Briton, 25th of Febuary 1802) and again in 1808, the Dublin Evening Post for the 26th of July 1808 reported of that ball that

One complication with the tune is that most of the published variants involve an irregular second strain. Most country dancing tunes are phrased in either 4, 8 or 16-bar strains; the Walker variant of our tune has an 8-Bar A strain followed by a 14-Bar B strain, both Dale (see Figure 11) and Button & Whitaker arranged it the same way. James Platts arranged it as an 8-bar A strain followed by a 6-bar B strain with an 8-bar C strain and Wheatstone & Voigt arranged it as an 8-bar A strain followed by a 10-bar B strain. Thomas Wilson in his 1816 Companion to the Ballroom arranged it in two 8-bar strains and added a footnote:

We've animated an arrangement of the first of Thomas Wilson's figure sequences for St Patrick's Day from his 1816 A Companion to the Ballroom (see Figure 11), we've done so using his

Montreal

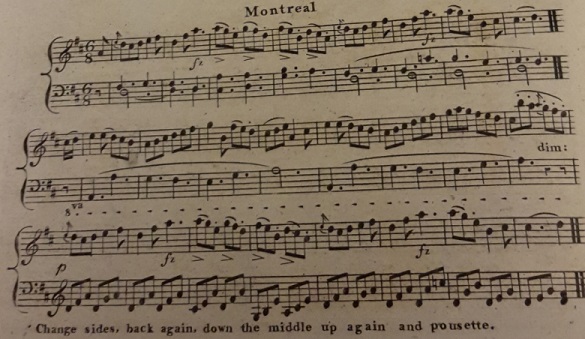

The second dance was Montreuil...(The Duchess of Dorset's Ball)  Figure 12. Montreal from Skillern & Challoner's 1809 8th Number

Figure 12. Montreal from Skillern & Challoner's 1809 8th Number

The Montreal tune was widely published in London in both 1809 and 1810, it can be found within at least a dozen dance collections published at around this date. The name of the tune remains a mystery however, it's not clear why it was named 1809 saw the erection of Nelson's Column in Montreal in dedication to the British Admiral Horatio Nelson, it's possible that the tune's name references this monument, though this seems unlikely (whereas Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square wasn't constructed until the 1840s). A Danish ship named the Montreal had been captured by HMS Brilliant in December 1807, the prize money for which was distributed in January 1809 (The Star, 18th January 1809), it's possible that this success was what the tune was named in reference to, though once again this seems improbable. Perhaps the unknown composer was from Montreal? All we can do is speculate. Regardless of the origins of the tune it was clearly a hit in 1809. The precise chronology of publication can't be known but examples include: Halliday & Co's Collection of Dances for 1809, Wheatstone & Voigt's 1809 4th Book, Skillern & Challoner's 1809 8th Number (see Figure 12), Goulding & Co's c.1809 15th Number, Dale's c.1809 15th Number, Davie's c.1809 23rd Number, Wheatstone's 24 for 1810, Fentum's 24 for 1810, Bland & Weller's 24 for 1810, Andrew's c.1810 23rd Number and Monzani's c.1810 11th Number. It can also be found in Goulding's 24 for 1811, Walker's 1812 29th Number and is referenced in both Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and in Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ballroom. Yet for all this publication history the tune is rarely mentioned in the newspapers, our event in 1810 is the only Ball for which I can positively identify that the tune was danced. This tune is an example of something that was popular back in 1810 but that was largely forgotten thereafter. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Skillern & Challoner's 1809 version (see Figure 12).

French Figure Dances

... French figure dances concluded the night's entertainment.(The Duchess of Dorset's Ball) We've studied the concept of French Figure Dances in previous papers. They were choreographed dances of a generally French origin, often arranged in a square formation; the term was sufficiently vague that it could refer to a Minuet, a Cotillion or even to a couple Waltz. You might like to follow the link to read an investigation of the term in relation to a society ball of 1803, or this second link that explores the general concept of figure dances. We can't know exactly what was danced at the Duchess' ball. As the last dance of the end of the evening it may have been something special, perhaps a Cotillion dance or maybe even an early Quadrille. Those involved in the dancing (whatever form the dance took) would have prepared their display-dance in advance, this performance would have been carefully prepared by the hostess and her friends, the other guests should have been suitably impressed.

Lady Madelina Sinclair

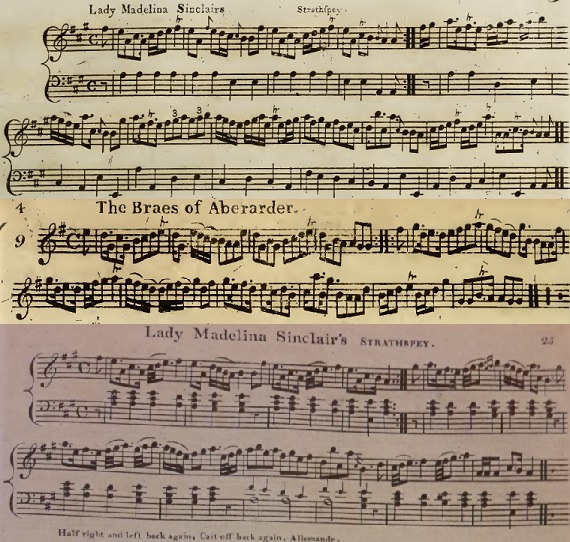

... the dancing commenced with a new reel, called Lady Madelina Sinclair.(The Duchess Dowager of Newcastle's Ball)  Figure 13. Lady Madelina Sinclairs Strathspey from Niel Gow's 1792 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (above), and The Braes of Aberarder from the 1794 4th volume of James Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (middle), and Lady Madelina Sinclair's Strathspey from Davie's 1803 8th Number (below).

Figure 13. Lady Madelina Sinclairs Strathspey from Niel Gow's 1792 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (above), and The Braes of Aberarder from the 1794 4th volume of James Aird's Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (middle), and Lady Madelina Sinclair's Strathspey from Davie's 1803 8th Number (below).

Lady Madelina Sinclair (1772-1847) was the second daughter of the 4th Duke of Gordon. Her sisters were numbered amongst the most elite of society hosts, her mother Jane Gordon (c.1748-1812) had been one of the most influential social dancers of her generation. Madelina married Sir Robert Sinclair (1763-1795) in 1789; after he died she went on to marry Charles Palmer (1769-1843) in 1805. By the date of our ball her name was Lady Madelina Palmer; meanwhile three of her sisters had become the Duchesses of Richmond, Manchester and Bedford. Madelina would have either been known to, or at least known of by, most of the guests at the Duchess of Newcastle's ball. She may even have been present at the ball in person.

We're informed that the tune was

Several tunes dedicated to Madelina Sinclair were in circulation in 1810, by far the most popular was named

Lady Madelina Sinclair's Strathspey may have been a successful tune but was it danced at our ball? We noted above that the tune was described as being

The tune is known to have been danced at one further ball of 1810 in addition to that of the Dowager Duchess of Newcastle. It was also, according to the Morning Post newspaper, danced at Hon. Mrs Knox's Ball (Morning Post, 30th April 1810): We've animated a suggested arrangement of J. Davies 1808 version and of Preston's 1795 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Madelina Sinclair (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

The Persian Dance

The second was The Persian Dance, composed in compliment to his Excellency Mirza Abul Hassan, which was likewise a great favourite.(Lord Sydney's Ball and Supper) The Ball was opened at eleven with The Persian Dance, by the Marquis of Hartington and Lady Barbara Ashley Cowper. About twenty couple followed...(The Countess of Shaftesbury's Ball) ... in the Persian Dance, this elegant foreigner, and his no less amiable partner, displayed all the graces...(The Barfield Ball at Broadstairs) The Persian Dance was composed by John Parry and was named in reference to the Persian ambassador to London, he was a regular attendee of society balls in 1810 (he is named among the guests of two of the balls above). It was an immensely popular tune for the season; we've written about it elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more.

Reel of Tulloch Gorum

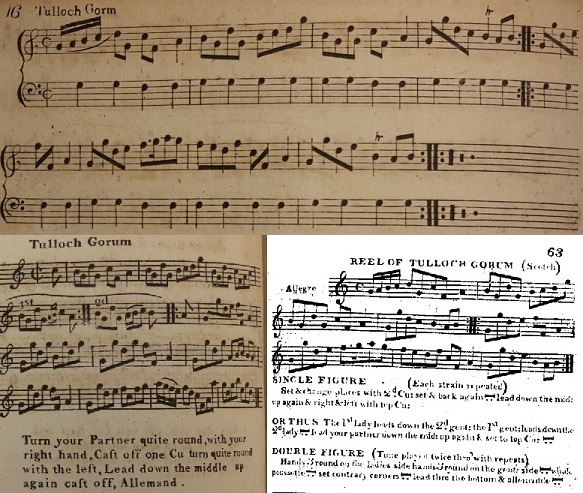

The amusements commenced with the reel of Tulloch-goram, by the Duchess of Manchester, Hon. Mr St Leger, and the Hon. Capt. Warrender.(The Princess of Wales's Grand Ball)  Figure 14. Tulloch Gorm from the c.1757 second volume of Robert Bremner's Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top), Tulloch Gorum from Thomas Skillern's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1791 (bottom left) and the Reel of Tulloch Gorum from Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ballroom (bottom right).

Figure 14. Tulloch Gorm from the c.1757 second volume of Robert Bremner's Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top), Tulloch Gorum from Thomas Skillern's collection of 24 Country Dances for 1791 (bottom left) and the Reel of Tulloch Gorum from Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ballroom (bottom right).

The

The tune named

The tune named the

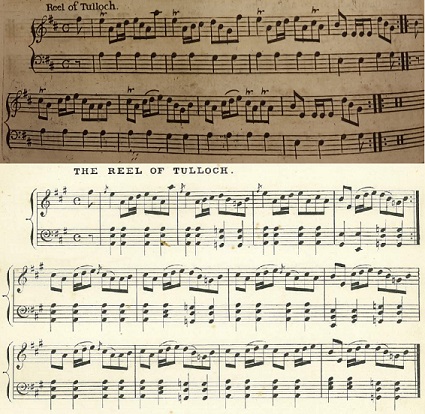

So which tune was danced at our ball? We're informed that the  Figure 15. Reel of Tulloch from the c.1761 eleventh volume of Robert Bremner's Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top) and The Reel of Tulloch from Joseph Lowe's 1862 2nd Book of The Royal Collection of Reels, Strathspeys & Jigs (bottom).

Figure 15. Reel of Tulloch from the c.1761 eleventh volume of Robert Bremner's Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (top) and The Reel of Tulloch from Joseph Lowe's 1862 2nd Book of The Royal Collection of Reels, Strathspeys & Jigs (bottom).

As a further consideration, the Scots Magazine for the 1st of January 1809 published a biography of Neil Gow that commented:

If we consider references from later in the 19th century then the identity of the tune becomes less certain. Our second tune, the Reel of Tulloch, would go on to become associated with a specific dance that would live on into the modern RSCDS dance repertoire. This dance was evidently a favourite of Queen Victoria, she mentioned it in her diaries from at least as early as 1843. The dancing master Joseph Lowe (1796-1866) described playing a Reel of Tulloch for Queen Victoria and her children several times in the 1850s; for example, a diary entry for 1856 recalls that

What can we say of the dance at our ball? It was probably a Reel of Three and was probably danced to the tune of Tulloch Gorum (but played as a reel rather than a strathspey). It may have had a choreographed sequence of steps and figures but may have involved an improvised routine. It was probably danced with vigour (or, as described above in 1804, with

The three dancers from our ball were named as We've animated suggested country dance arrangements of Tulloch Gorum from the Skillern collection of 24 for 1791 (which was duplicated in their collection for 1796, see Figure 14) and of Thomas Wilson's 1816 Double Figure. We've also animated a suggested country dance arrangement of Longman & Broderip's c.1781 version of The Reel of Tulloch. For futher references to the tune, see also: Reel of Tulloch (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

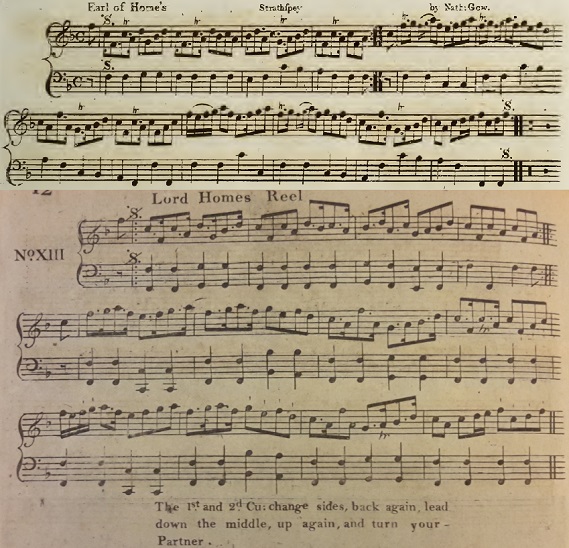

Lord Home's Reel Figure 16. Earl of Home's Strathspey from Neil Gow's 1792 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (top) and Lord Homes Reel from Campbell's c.1805 20th Book.

Figure 16. Earl of Home's Strathspey from Neil Gow's 1792 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels (top) and Lord Homes Reel from Campbell's c.1805 20th Book.

Lord Hume was led off by Lord Ashbrooke and the Duchess of Manchester(The Princess of Wales's Grand Ball) This tune was widely published in London in both the 1790s and 1800s, it was variously known as Lord Home's Reel, Lord Hume's Reel, the Earl of Home's Strathspey and other similar variants. The dedicatee was Alexander Home, 10th Earl of Home (1769-1841), he sat in the House of Lords at the date of our ball, it's possible that he was a guest at the Princess of Wales' ball. He had married a daughter of the Duke of Buccleuch in 1798.

The tune was first published in Edinburgh in Neil Gow's 1792 Third Collection of Strathspey Reels, it was issued under the name

The tune had been popular with the Royal family. The Kentish Gazette newspaper (for the 10th August 1798) reported on a royal ball at which The dance at our 1810 ball was led off (once again) by the Duchess of Manchester, her partner this time was Lord Ashbook. Ashbook has featured in our research before; his first wife was Deborah Ashbook (c.1780-1810), she died in March 1810 leaving him a widower, he evidently took to dancing shortly thereafter. Lady Ashbook had composed several popular country dancing tunes including Ferne Hill (a tune better known as The Tank), you might like to follow the link to read more. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Budd's 1794 version, of Hime's 1799 version and of Campbell's c.1805 version (see Figure 16). For futher references to the tune, see also: Earl of Home at The Traditional Tune Archive.

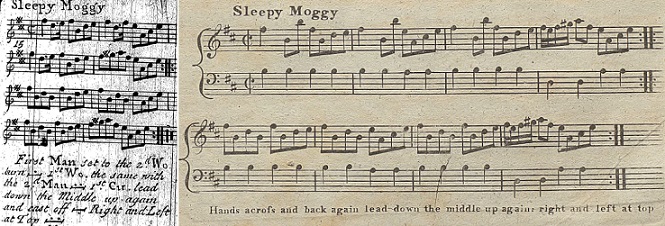

Sleepy Moggy / Sleepy Maggy

Sleepy Moggy was the second dance; it was given with admirable spirit by the Duchess of Manchester, Lady Cowper, &c.(The Princess of Wales's Grand Ball)

This tune is readily identifiable as it had been widely published in both London and Edinburgh since the 1750s. The London publications invariably named the tune  Figure 17. Sleepy Moggy from Johnson's c.1751 6th volume of A Choice Collection of 200 favourite Country Dances (left) and from William Campbell's c.1802 17th Book (right).

Figure 17. Sleepy Moggy from Johnson's c.1751 6th volume of A Choice Collection of 200 favourite Country Dances (left) and from William Campbell's c.1802 17th Book (right).

The first publication of the tune that I can find was in London in the c.1751 6th volume of Johnson's A Choice Collection of 200 favourite Country Dances (as In addition to having been danced at the Princess of Wales's Grand Ball in 1810 it is also known to have been danced at one other early 19th century event, the Aberdeen Journal for the 30th of June 1800 reported that it was the second dance at a recent Duchess of Gordon's Ball.

We don't know who led off this dance at our event in 1810 but once again the Duchess of Manchester is named as having danced it with We've animated a suggested arrangement of William Campbell's c.1802 version (see Figure 17) and of James Platts's 1810 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Sleepy Maggie (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive.

The Opera Hat / The Russian Dance

... was opened by the Hon. Miss Maynard, and Miss Henniker, to the delightful tune of The Opera Hat, and followed by about 30 couple.(The Barfield Ball at Broadstairs)

This tune was a popular favourite in both 1809 and 1810, it was widely published in London under the names

Conclusion

We've seen a diverse collection of tunes being danced at our balls of 1810. They include several tunes or dances of Irish derivation, also Scottish and English dances; a French figure dance and Waltzes were also enjoyed. 1810 was a year at which the Country Dance continued to dominate the ballrooms of the aristocracy but other dance forms were increasingly of interest. We've read of a moderately diverse collection of events: balls held at large town-houses, at Royal Palaces and at popular spa towns. Many of the events were We'll leave the investigation here however. If you'd like to recreate a ball of 1810 then the tunes and dances we've investigated in this paper would be very suitable to be used. Perhaps you could create a video of your ball to share with the world? If you have any further information to share, perhaps involving these or any other dances, then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2024

All Rights Reserved