|

Paper 49

Spanish Country Dancing

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 15th March 2021, Last Changed - 12th November 2021]

Spanish Country Dancing was a phenomenon that arrived in England during the 1810s. These dances achieved a reasonable degree of popularity in Britain by the 1820s. This paper will investigate what is known about this innovation in social dancing and consider the extent to which the dance form was experienced in the English ballroom of the 1810s and early 1820s. We'll review the major surviving texts on the subject, attempt to reconstruct the form of the dance and consider the effect that the dance had on the broader social dancing industry.

Figure 1. Detail from Davidson's 1856 Pop Goes the Weasel, The Spanish, & Forty Other Country Dances. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library. The form of this dance is similar to that of a Spanish Country Dance of our period, though not exactly the same.

The Danses Espagnole or Spanish Country Dances

The term Spanish Country Dance is one that emerged in Britain no later than the year 1816, it referred to a variation of the English Country Dance that was understood to be of Spanish origin; the earliest and most prominent exponent of the form was the London based dancing master Edward Payne (1792-1819). We've written of Payne's Spanish Country Dances in another paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. Several other prominent dancing masters in London went on to teach the Spanish Country Dance thereafter, the concept lived on in Britain into the later 19th century (see, for example, Figure 1).

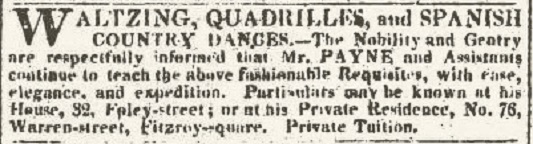

The date at which these dances entered Payne's repertoire is uncertain. Their absence from his 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room (and associated advertisements) suggests that they were not a core part of his tuition in 1814, they probably came to prominence either in late 1815 or in early 1816. He explicitly referred to them as being within his repertoire in an advert of mid 1816 (Morning Post, 27th May 1816, see Figure 2) but seems not to have published any example dances prior to 1817. I know of no clear evidence for any other British dancing masters teaching these dances before Payne; they may of course have done so, but the dance form seems not to have been widely known in London at any earlier date.

We'll investigate the form of the Spanish Country Dance more fully in due course, a brief summary will suffice for now: the main characteristics of the dance are that the first couple in a longways set would start the dance improper (the man on the ladies' side of the set and the lady on the men's side), the figures were issued in Spanish and the dancing involved waltz inspired rhythms and turns. Some sources (such as Wheatstone's 1820 collection of Spanish Dances) emphasise that Spanish Country Dances fuse Quadrille dancing figures into the form of the English Country Dance. The dance would be recognisable as a variation of the regular English Country Dance, yet it was sufficiently unusual to be considered as something distinct and new. Figure 1 depicts an evolution of the Spanish Country Dance from later in the 19th century.

The concept of Spanish dancing wasn't new in London at this date, several waves of Spanish influenced stage dances has impressed Londoners over the preceding decades. Music sellers such as James Platts made and sold Spanish Tambourines and Castanets (with suitable music) for the London dance market in the late 1790s and early 1800s, we've written more of Platts elsewhere; we've also discussed the performance of the Spanish Boleros at an 1809 Ball, the Guaracha stage dance of 1812 and the Zapateado and Cachucha stage dances of 1814 (all of which were considered to be Spanish dances) in previous papers; the Fandango was another Spanish stage dance known in London. Several dancing masters offered tuition in Spanish Steps and Spanish Dances throughout the 1810s; Mrs Burghall, for example, advertised that she taught the present fashionable style of WALTZING and SPANISH DANCING as practised on the Continent and in this Country in early 1816 (Morning Post, 17th February 1816). The extent to which the public of 1816 would distinguish between the new Spanish Country Dances and the more general Spanish Dances isn't clear, many of the surviving references are indistinct. We've previously studied a Ball of 1813 which might have included Payne's Spanish Country Dancing, it's entirely possible that Payne himself was teaching the dances as early as 1813.

Figure 2. Payne's first reference to Spanish Country Dances , Morning Post 27th May 1816. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive ( www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk).

The Spanish Country Dances are understood to have been influenced by the Waltz. The Waltz couple dance had been growing in popularity in Britain since around the year 1800, we've written of the Waltz elsewhere. Waltz tunes were used for English Country Dancing from at least as early as 1790 (James Platts once again being an early proponent of the form). Dancing masters such as Thomas Wilson (1774-1854) promoted the Waltz Country Dance as a unique dance form from around the year 1815, an early example of his dances can be found in his Le Sylphe collection for 1815. The Spanish Country Dance may have been Payne's response to Wilson's new dance (or vice versa). Wilson actively promoted himself as the inventor of the Waltz Country Dance; Payne did almost the same thing for the Spanish Country Dance, at least by implication. It's unlikely that either can genuinely claim to have invented their respective dance forms, but they may have promoted them at an earlier date than their London rivals. 1816 was a year for new beginnings in Britain, several new dances were sweeping the nation in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. The Waltz had finally gained traction in the ballrooms of the gentry and the Quadrille (a new dance that was also promoted by Payne) was rising to prominence; 1816 was the perfect date for new dances to interest the general public.

The extent to which the Spanish Country Dance was genuinely of Spanish origin is uncertain. The dance as promoted in London was understood through an English lens, it was no more Spanish than a Reel was Scottish or a Quadrille was French; national identifiers referred more to the style of the dancing than to the geographic origin of the dance, the place of publication, or even the nationality of the creator. The Spanish Country Dance as understood in London of 1816 might have been an entirely English invention. Indeed, another dancing master named G.M.S. Chivers invented Swedish Country Dances later in the 1810s, these dances held no connection to Sweden, he selected the name Swedish simply because he could. My non-expert impression is that the Spanish Country Dance probably was of genuine Spanish derivation, it may perhaps have been danced by the allied troops during the Peninsula War of 1807-1814 and thereby brought back home, but this is not an established fact. One could imagine a fusion of British and Iberian dancing styles being brought together in the Spanish Country Dance, then exported elsewhere as an anglicised reinterpretation of the contradanza. The potential Spanish origins of the dance are a matter for speculation however, this paper will focus on what was being danced in Britain, it may or may not be relevant to what was being danced in Spain (and elsewhere around the world) at a similar date.

Most of what's known of London's Spanish Country Dancing of the 1810s is derived from Payne's own publications on the subject; Thomas Wilson is also understood to have published a text on the Spanish Country Dance (now believed lost) in 1817, G.M.S. Chivers too would publish his own guide in 1819. We'll go on to review the available information from these works below, together with the rare example choreographies found in other publications of a similar date.

Edward Payne's Dances Espagnol and Danses Espagnoles Publications of 1817

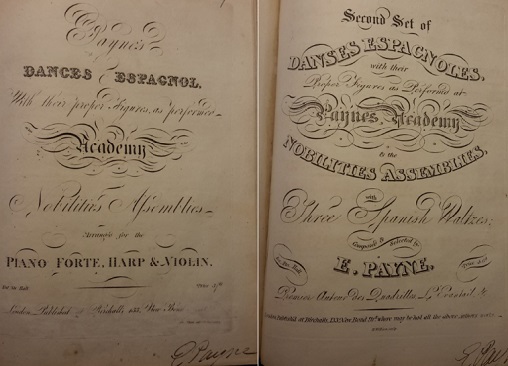

Figure 3. Payne's 1817 Dances Espagnol (left) and Second Set of Danses Espagnoles (right). Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(9.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Edward Payne published two collections of his Spanish Country Dances either in 1817 or perhaps in very early 1818 (see Figure 3). We can estimate the publication date to 1817 as he advertised a third collection (now, as far as I can determine, lost) in early 1818 (Morning Post, 5th February 1818) and the content of the first two collections refer to the existence of his 1817 Quadrille Fan. These collections both begin with the same shared preface (see Figure 4); one might expect the preface to describe the form of the dance but it is rather an essay on his own accomplishments. The text of the prologue is reproduced in full below.

The prologue is then followed, in the first collection, by six unnamed tunes (half in a 2/4 time signature and half in 6/8) and some suggested figures for each tune. The figures are given in a mixture of Spanish and English with no explanation of the Spanish terminology. For example, the second set of figures is given as: Cadena, Allemanda entera, Paseo, Pilota and Waltz . The reader was evidently required to already be familiar with this Spanish terminology before proceeding. A footnote explains that the waltz figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over . All of the figure sequences end with this same waltz instruction and all share the same footnote. The music in each case is arranged into three repeated strains of 8 bars seemingly with a final repetition of the first two: AABBCCAB. The arrangement of figures to music is not at all obvious; Payne's later publications indicate that the second set of figures would require 40 bars of music plus however much is taken for waltzing, some other arrangement of the music might therefore be required; this might suggest an AABBCC arrangement with the waltzing included, and AABBC without.

The second collection shares a similar form to that of the first; the prologue is followed by six unnamed tunes (five of which are in 2/4 time signature and one in 6/8), followed by four unnamed Waltze Espagnol tunes without dance figures. The figures for the Spanish Country Dances are given in both Single and Double arrangements (the same style adopted by Thomas Wilson for his Country Dance publications of the 1810s), the double arrangement requires the music to be played twice through. The double arrangements duplicate the figure sequences from the first publication, the single arrangements were new however. The choreographies once again end with an optional instruction to Waltz . The requirement to Waltz to a 2/4 time signature tune is unusual, this seems to have been an important aspect of Payne's Spanish Country Dances; it's more normal to waltz to a triple time musical arrangement - Payne would go on to explain in his 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing that the waltz step had to be danced in four movements, and that it is impossible to convey by writing exact rules to keep precise time to the Music, the Ear is the only guide that can be depended on .

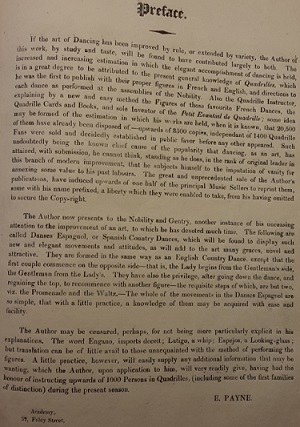

What follows is the shared prologue from these two publications (see Figure 4); we've annotated the text with additional commentary (delimited by square brackets) where necessary to explain some of the more obscure references. The content relevant to Spanish Country Dancing begins in the second paragraph:

Figure 4. Payne's 1817 Preface to his Dances Espagnol. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.726.m.(9.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

If the art of Dancing has been improved by rule, or extended by variety, the Author of this work, by study and taste, will be found to have contributed largely to both. The increased and increasing estimation in which the elegant accomplishment of dancing is held, is in a great degree to be attributed to the present knowledge of Quadrilles, which he was the first to publish with their proper figures in French and English, and directions to each dance as performed at the assemblies of the Nobility.

[Payne claimed to have been the first London publisher to issue Quadrille collections, we've discussed the rise to prominence of the Quadrille in 1816 here.]

Also the Quadrille Instructor, explaining by a new and easy method the Figures of those favourite French Dances

[a work Payne published in 1816]

, the Quadrille Cards and Books

[thumbnail publications with the list of figures for specific quadrille dances printed on them, something a dancer could discreetly check in-situ at a ball]

, and sole inventor of the Petit Evantail de Quadrille

[Payne's 1817 Quadrille Fan]

; some idea may be formed of the estimation in which his works are held, when it is known, that 20,500 of them have already been disposed of - upwards of 3,500 copies, independent of 1400 Quadrille Fans were sold and decidedly established in public favor before any other appeared. Such undoubtedly being the known chief cause of the popularity that dancing, as an art, has attained, with submission, he cannot think, standing as he does, in the rank of original leader in this branch of modern improvement, that he subjects himself to the imputation of vanity for annexing some value to his past labours. The great and unprecedented sale of the Author's publications, have induced upwards of one half of the principal Music Sellers to reprint them, some with his name prefixed, a liberty which they were enabled to take, from his having omitted to secure the Copy-right.

The Author now presents to the Nobility and Gentry, another instance of his unceasing attention to the improvement of an art, to which he has devoted much time. The following are called Danses Espagnol, or Spanish Country Dances, which will be found to display such new and elegant movements and attitudes, as will add to the art many graces, novel and attractive. They are formed in the same way as an English Country Dance, except that the first couple commence on the opposite side - that is, the Lady begins from the Gentleman's side, the Gentleman from the Lady's. They have also the privilege, after going down the dance, and regaining the top, to recommence with another figure - the requisite steps of which, are but two, viz. the Promenade and the Waltz, - The whole of the movements in the Danses Espagnol are so simple, that with a little practice, a knowledge of them may be acquired with ease and facility.

The Author may be censured, perhaps, for not being more particularly explicit in his explanations. The word 'Engano', imports deceit; 'Latigo', a whip; 'Espejos', a Looking-glass; but translation can be of little avail to those unacquainted with the method of performing the figures. A little practice, however, will easily supply any additional information that may be wanting, which the Author, upon application to him, will readily give, having had the honour of instructing upwards of 1000 Persons in Quadrilles, (including some of the first families of distinction) during the present season.

This prologue is fascinating but it does little to explain the dance to the reader, those deficiencies would be addressed in a suffix to Payne's next major work.

Edward Payne's 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing

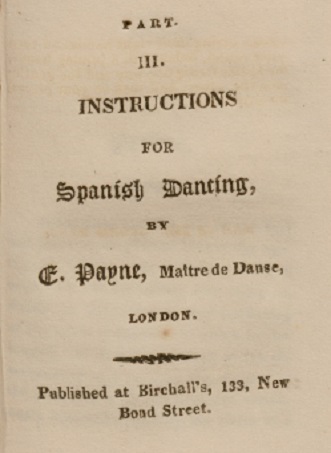

Figure 5. Payne's 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing.

Payne's Quadrille dances were proving ever more popular, his publishing priorities were appropriately focussed on them in both 1817 and 1818. He published his Quadrille Dancer in March 1818 (Morning Post, 11th March 1818), this was arguably the single best publication to be issued in London explaining the newly fashionable Quadrille dance; he didn't forget the Spanish Country Dance however, the book included a final section of Instructions for Spanish Dancing (see Figure 5). These 1818 instructions are the single most detailed source of information we have to describe how London's Spanish Country Dances were actually to be danced. The entire work is transcribed below.

The instructions begin with a preface which is followed by a brief explanation of the construction of a Spanish Dance, the Steps used, how to dance the Promenade Step, how to dance the Waltz Step and how to use the arms when waltzing. This is all followed by a detailed description of the individual figures with twelve example choreographies (duplicating those from his two 1817 collections). It ends with a translation of the Spanish terminology. What follows is a transcription of the textual part of the work, omitting only the description of the figures which are reproduced in a slightly different form further below.

Part III. Instructions for Spanish Dancing, by E. Payne, Maitre de Danse, London. Published at Birchall's, 133 New Bond Street

It has been said by one of the best and most accomplished Men of the age that he held it to be a primary duty in every Man, to contribute something towards the improvement and perfection of the art or profession to which he belonged. If there is any merit in the observance of this maxim, the Author of the following work has long and assiduously laboured to justify his claim to a share. He has already Published a first and second set of Danses Espagnoles or Spanish Country Dances, both of which, by a rapid and extensive sale, received the most unequivocal proofs of public approbation. This flattering consideration combined with the numerous and urgent entreaties of many Ladies and Gentlemen calling for additional and diversified examples of these favorite Dances, have induced him to present the Public with the following, these Dances have now become so popular, and their characteristic distinctions are so fully explained in the Authors former set, that any further remarks here on these Topics, might be deemed superfluous.

To the first and second set of Danses Espagnoles, it has been objected that the Author has been too sparing of the translation, the truth is, it is no easy matter to supply a translation from the Spanish which shall preserve with fidelity the Spirit and idiom of that Language. But the Author having in composing the following work, availed himself of a Nobleman alike distinguished for rank and talent; this defect, will now, he hopes be found tolerably supplied. In such Figures as the Mona, Engano, Pilota, Barilete, Arcos, Latigo, Espejos, Favorita, and Allemanda Sostenida, the translation being of no avail to those unacquainted with the Spanish Danses, the method of performing them are fully explained.

If any further explanation should however still be required, the Author upon application, will readily afford it. Indeed he can truly affirm, that neither time nor pains have been spared to render the following worthy of the extensive patronage, with which his former works have been honour'd.

E. Payne, Salle de Danse, 32 Foley Street.

A Spanish Dance is formed precisely in the same manner as an English Country Dance, except the 1st couple, which commence on the opposite sides, that is the lady begins from the gentlemans side, and the gentleman from the ladies, this rule must be observed by all the couples, when they commence from the top, when they have gained the bottom, they return to their own sides, the couple that called the dance have also the privilege, after going down and regaining the top, to recommence with an other figure.

Two steps are only required in the Danses Espagnoles, the promenade and the waltz, those ladies and gentlemen who are possessed with an Ear for Music, and have acquired waltzing, will find no difficulty in applying their steps to these dances, which are in general in 2-4 and 6-8 time, and require the promenade step to be counted into two, and the waltz into four movements; Waltz tunes being composed in 3/4 and 3/8 time, require the steps to be counted and divided into three and six movements, indeed I am of an opinion, that it is impossible to convey by writing exact rules to keep precise time to the Music, the Ear is the only guide that can be depended on.

This step commences from the 1st or 3rd pos. with the *left foot before, you make a step forward with the left foot into the 4th pos. then bring the right up to the left, into the 1st pos. afterwards with the knees perfectly straight, rise on your toes and quickly let both heels fall to the floor, repeat the same with the right foot, then again with the left, and as often as the figure of the dance may require.

This step occupies One bar in 3/4 time, suppose the bar contain three crotchets, the step forward answers to the first note, bringing the foot behind to the second, and the rise and fall answers to the third crotchet, in 2/4 or 6/8 time, the step is performed in the same manner, the alteration that occurs must be regulated by the Ear.

* The lady always commences with the right foot before.

To perform this step place your left foot into the 2nd pos. turning the foot a little inwards, which will incline your left shoulder round, then place the right foot behind into the 5th pos. and turn on your toes half round, finishing with the right foot before in the 3rd pos. at the same time let the two heels fall to the floor, then on your toes advance, the right foot well turned outwards to the 4th pos. afterwards step round with the left to the 2nd pos. on your toes, then bring the right foot to the left into the 1st pos. at the same time let both heels fall to the floor, the same again repeated as often as the figure of the dance may require. This step occupies Two bars.

To perform this step together, at the time the gentleman places his left foot into the 2nd pos. the lady advances her right into the 4th pos. as the gentleman places his right foot behind and turns half round, the lady steps round with the left and brings her right foor into the 1st pos. the gentleman now advances his right foot into the 4th pos. while the lady steps with her left into the 2nd pos. the gentleman then steps round with his left foot into the 2nd pos. and brings the right up to the 1st pos. as the lady places her right foot behind in the 5th pos. and turns on the toes half round, which completes the step.

In waltzing there are a variety of attitudes of the Arms, the most fashionable is the open position, formed as thus, the gentleman places his right hand to the ladys' waist, and takes her right with his left, each arm forming a curve, raised the height of the ladys' shoulder, the ladys' left hand rests on the gentlemans right shoulder, the same reversed.

Arcos ... Arch

Barilete ... A sort of ligature

Cadena ... Chain

Engano ... Deceit

Esperjos ... Looking-Glass

Entera Allemanda ... Whole Allemande

Favorita ... Favorite

Frentis ... Front

Latigo ... Whip

Mona ... A knot that binds the Hair

Media Cadena ... Half Chain

Paseo ... Walk

Pilota ... Pilot

Rueda ... Wheel

Sostenida Allemanda ... To Support

Tornillo ... Turn

Trionfa Paseo ... Walk in Triumph

Payne then went on to explain how each of the figures are danced, these additional instructions are transcribed below. It will be seen that this text addressed many of the limitations of Payne's initial two collections of Danses Espagnole, as modern enthusiasts we have sufficient information to attempt a reconstruction of the dance form.

Other writers on the Spanish Country Dance

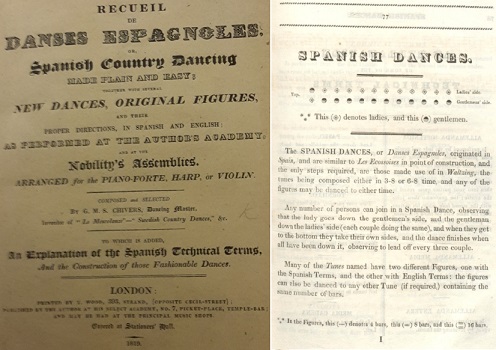

Figure 6. Chivers' 1819 Recueil de Danses Espagnoles (left) and Spanish Dances from his 1822 Modern Dancing Master (right).

Payne wasn't the only British dancing master to write of the Spanish Country Dance. Several others did so too, just never in so much detail as Payne.

Thomas Wilson, for example, published a brief work on the subject in 1817 (I know of no surviving copies) and G.M.S. Chivers did so in 1819 in his Recueil de Danses Espagnoles (see Figure 6, left). Chivers' book borrowed heavily from that of Payne, Chivers must surely have owned a copy of Payne's book and worked from that. Payne died in early 1819, this may have empowered Chivers to reuse Payne's text with impunity. A few minor differences do emerge, most notably that Chivers thought the most suitable music was that arranged in either 3/8 or 6/8 time signature (i.e. a waltz rhythm) rather than the 2/4 and 6/8 time signatures favoured by Payne; he also emphasised that When the first couple have gone down three, the second couple begin, and so they continue leading off every three couple. . Beyond these notes little variation can be found.

Chivers went on to include much of the same information once again in his 1821 The Dancers' Guide and in his 1822 The Modern Dancing Master, though in a more abridged format; he added that the Danses Espagnoles, originated in Spain for these publications (see Figure 6, right).

The Lowe brothers in Scotland then included much of this same information in their Ball-Conductor and Assembly Guide, the first edition of which was published in 1822. I've studied the 1831 third edition of this work as rewritten by Joseph Lowe in 1830; the information on Spanish Country Dancing for the third edition appears to be derived from what Chivers had previously published in his Modern Dancing Master, which in turn was loosely derived from Payne's Instructor. Their dance figures are in some cases quite different to those of Chivers and Payne, they appear to have corrected and improved upon their Chiverian source material in several places (and introduced errors in others). We'll review their descriptions of the figures alongside those of Payne and Chivers shortly.

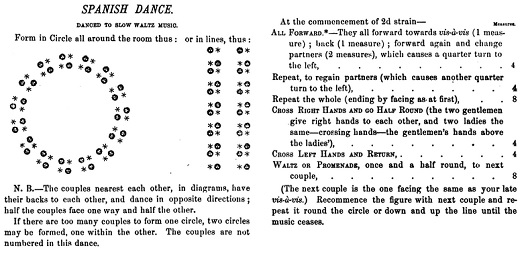

The Guaracha / The Spanish Dance / The Spanish Waltz

The best known Spanish Country Dance today, and also in the 1810s, is a dance variously known as The Spanish Dance, The Spanish Waltz or in many of the older sources The Guaracha . The modern dance begins with the first couple(s) in a longways set (or circular set) standing improper; two couples typically set in and out then pass their ladies one place round, repeating four times to return back to places; then star right and left, then waltz turn their partner to progress following the track of a pousette (see also Figure 9). A variation of these figures date back to at least the 1810s.

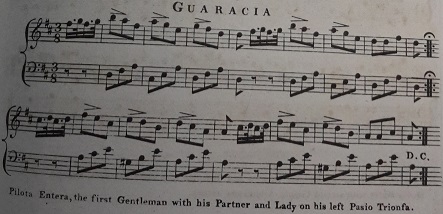

Figure 7. Guaracia from Hime & Son's c.1820 Spanish Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.1480.l.(37.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

We've discussed the 1811 Guaracha stage dance (most famously performed by Miss Smith to the accompaniment of her castanets) in a previous paper. Her tune was widely published as a Country Dance in both 1811 and 1812; examples of publication include Goulding's c.1811 22nd Number, Dale's c.1811 18th Number, Hodsoll's c.1811 15th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1811 6th Book, Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 15th Number, Walker's c.1812 30th Number, Button & Whitaker's 1812 18th Number and Wheatstone's collection of 24 for 1812. Bland & Weller also issued the tune under the name The Spanish Waltz in their collection of 24 for 1813. Some of these publications offered dancing figures for the tune, those that did suggested fairly ordinary English Country Dance arrangements, there's nothing to suggest the unique dance that would subsequently become associated with the tune at this early date.

Something changed however, for some reason this particular tune came to be associated with the figures of a Spanish Country Dance. The combination may have emerged in London and may have had no significance beyond the tune being popular and being associated (in the mind of Londoners) with Spain. Thomas Wilson in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room printed the Guaracha tune under the name Guaracha Dance or Carthaginian Fandango without any figures, he included it in the section that was dedicated to Minuets and Gavots, he thereby implied that the tune had some special purpose. Wilson is also understood to have printed a short publication (now lost) on this dance. Payne, in his 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing, described a Spanish Country Dancing figure named Pilota which involved four people joining hands, advancing, retiring and then changing places with their parter, repeated four times over (which must surely be the origin of the modern figure); he added that This is the only Spanish Figure generally known, it is performed various ways, and by many termed the Guracha, being often danced to a Spanish Tune of that name. . This particular tune and figure combination was evidently becoming popular. Hime & Son of Liverpool published a version of the tune named Guaracia in their c.1820 Spanish Dances (see Figure 7), they offered an arrangement of the figures somewhat consistent with those implied by Payne (Pilota, Pasio Trionfa ). Chivers in his 1821 The Dancers' Guide described The Guaracha as a Spanish Country Dance in a similar form once again: Set all four and change places with partners - set and change places at the sides - set and change places with partners - set and change places at the sides - pousette at top to places (four parts or thirty-two bars). This figure is performed various ways, and is generally danced to the Guaracha Waltz, or as a Medley Dance. . It's perhaps worth noting that Chivers defined the word Waltze to mean the same thing as Pousette within the context of a Spanish Country Dance, his figures are therefore very similar to the best known modern variant.

The 1831 third edition of the Lowe Brothers' Ball Conductor and Assembly Guide (printed in Edinburgh) included another recognisable variation of the dance instructions but associated them with a tune named The Saraband; they gave the figures as Pilota, Rueda fixado e tornilla, Valza . Mons Boulogne's Glaswegian 1827 The Ball-Room or the Juvenile Pupil's Assistant printed The Guaracha under the title of Spanish Dance with a minor variation of the modern figures but arranged as a Quadrille. This combination of the Guaracha tune with a defined set of Spanish Country Dancing figures had evidently become meaningful in Britain at some point in the later 1810s.

Many later variations of the dance are known, some dropped the Guaracha title and instead presented this popular arrangement simply as The Spanish Dance (see, for example, Figure 9). The Library of Dance website tracks numerous variants of this dance across the later 19th century, you might like to read their text to learn more; additional information is available from the Contrafusion website.

We've animated a suggested arrangement of Hime's c.1820 version of the dance (see Figure 7) here.

The Figures of the Spanish Country Dance

The following table contains a parallel explanation of the figures of the Spanish Country Dance combined from several different source works. Any references to Payne refer to his 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing; the references to Chivers are to his 1819 Recueil de Danses Espagnoles and Lowe indicates the 1831 third edition of their Ball-Conductor and Assembly Guide (though the content is likely to have been similar in their 1822 first edition of that work). Many of the figures are described in all three documents. The figures are listed here in alphabetical order, they appear in a different sequence in the various source works, they're resequenced here for ease of reference.

Some of the figures have similar descriptions across the source works. Others are described quite differently. Chivers was a relatively close copyist of Payne, whereas the Lowe text (at least as updated by Joseph Lowe c.1830) can be very different to the earlier works. Chivers added three figures that were not mentioned by Payne: these are two half figures (Media Engano and Allemanda Media) and the third was the Waltze. All three of these figures are implied in Payne's text, they're not entirely new to Chivers. The later Lowe text did add some genuinely new figures not known from the earlier works. The explanations below are quoted directly from the source works, any Notes included are our observations on those descriptions.

| Figure | Explanation |

|---|

| Allemanda |

| Lowe, 1831: (allemande,) the same figure as promenade, only the hands joined behind backs. |

|

| Allemanda Entera |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman and lady join their left hands behind, and their right hands before and allemand quite round, the same again repeated reversing the Arms, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: (or the whole Allemand,) is performed the same [as the Allemanda Media], and repeated again by reversing the hands (8 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: or enteramente, (allemande wholly); swing corners, or turn each of those at the corners by the allemande. |

| Notes: the Lowe text appears to have swapped this figure with the Allemanda Sostenida |

|

| Allemanda Media |

| Chivers, 1819: (or the Half Allemand,) is performed by the lady and gentleman joining right hands in front and their left behind, and turn quite round, (4 bars.) |

|

| Allemanda Sostenida |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman and lady join or link arms and turn quite round, the gentleman joins with the 3rd lady, while his partner joins with the 2nd gentleman, the 1st couple then turn quite round, in the centre again, the gentleman joins with the 2nd lady and his partner with the 3rd gentleman, Sixteen bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: (or the Support Allemand,) is performed by the lady and gentleman joining arms, and turning quite round, the gentleman then joins arms with the third lady, while his partner joins with the second gentleman, then turn your partner quite round, again in the centre, the gentleman then joins with the second lady, while his partner does the same with the third gentleman, to places (16 bars.) This must be performed from the centre. |

| Lowe, 1831: (the support allemande); the Gentleman puts his hand behind the Lady's back, while she rests her arm on his. |

| Notes: the Lowe text appears to have treated this figure an alias of the Sostenida embrace. |

|

| Arcos |

| Payne, 1818: The 2nd and 3rd couples hold up hands, forming an arch, while the 1st couple pass under, Four bars. |

| Chivers, 1819 (or, The Arch): is performed by the second and third couples holding their hands up, forming an arch, and the first couple passes under, and cast up one couple. (4 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (arches), formed by one or more couples holding up their hands joined, while others pass under them. |

|

| Barilete |

| Payne, 1818: The 1st gentleman casts off outside to the 3rd couple, then up again, his partner beginning to move down as the gentleman moves up, so as to meet and make an

obeisance to each other between the 2nd and 3rd couples, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is performed thus: the first Gentleman casts off behind to the third couple, and as he moves up, his partner moves down, and meet each other between the second and third couple, making their obeisance. (8 bars.) |

| Notes: see also the Figura Barrilete figure |

|

| Barrilete |

| Lowe, 1831: (a sea phrase, signifying a particular ligature made round the mast,) the waltz step twice. |

|

| Cadena |

| Payne, 1818: The four exchange situations, in passing the gentlemen give their right hands to their partners and the left to the other ladies, the same back again, Eight bars. |

Chivers, 1819: This is performed the same as in Right and Left, observing to give right and left hands in passing. (8 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (a chain), right and left. |

| Notes: see also the Media Cadena figure |

|

| Colmo |

| Lowe, 1831: (the top); a colmo, at the top. |

|

| Copula |

| Lowe, 1831: (couple); primera copula, first couple. |

|

| Engano |

| Payne, 1818: The 1st couple sets to the 2nd and turns the 3rd then sets to the 3rd and turns the 2nd. Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is that the first couple sets to the second, and turns the third, then sets to the third and turns the second. (16 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (deceit); set to one person, and turn another; or first couple set to the second, and turn the third; then set to the third, and turn the second. |

| Notes: see also the Media Engano figure |

|

| Espejos |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman joins his right hand with the lady on his right, and wheels round to the top, the lady at the same time joins her left hand with the gentleman on her left, wheels round and meets her partner, the same back again, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: The gentleman joins right hands with the lady at his right, they swing and exchange places, at the same time his partner joins left hands with the gentleman at her left, they swing and exchange places, the same repeated, back again to places. (8 bars.) This must be performed from the centre, with the top couple. |

| Lowe, 1831: (looking-glasses), the Gentleman joins hands across, with the Lady on his right, and, holding them well up, she turns round to the left, which brings the arms into the form of a mirror to each, when they turn fully round; at the same time, the Lady does the same with the Gentleman on her left. This must be performed from the centre, or after the first couple have done a figure that takes them below the second. |

|

| Favorita |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman gives his right hand to his partner and the left to the lady on his left, holding them up, while the 1st lady passes under, in the same manner the 1st lady holds up her hands with her partner, while the 2nd lady passed under, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is to advance and retire. (4 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (favourite), the Gentleman gives his partner his right hand, and the second lady his left; then the first Lady passes under his arms, and the Gentleman follows her; after which the second Lady does the same. |

|

| Figura Barrilete |

| Lowe, 1831: the Gentleman goes down two couples behind back, with the waltz step, making an obeisance to his partner after he passes the first, and also after he passes the second; when he returns, his partner commences at the top, and finishes between the third couple, while he finishes between the second. |

| Notes: see also the Barilete figure |

|

| Frentis |

| Payne, 1818: The lady and gentleman or the two ladies and the two gentlemen advance and retire, twice over occupies four bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is to lead down the middle, and back again, (8 bars.) This figure may be performed either by leading with one hand, or by Waltzing; the latter is more generally done. |

| Lowe, 1831: or frenesi, (phrenzy), advance and retire. |

|

| Hondo |

| Lowe, 1831: (the bottom); a hondo, at the bottom. |

|

| Latigo |

| Payne, 1818: The two gentlemen take their partners by the left hand, with their right, and pass them round behind, then half right and left, the two gentlemen pass the ladies round as before, and finish the right and left in their places, Sixteen bars. |

| Chivers, 1819 is performed by the two gentlemen joining right hands with their partners' left, and pass them round behind, and half right and left; the same is again repeated, and half right and left to places. (16 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (the lash of a whip), two Gentlemen give their Ladies their right hands; the Ladies pass round them (in the manner a lash goes round any thing struck); then all four do half right and left; the same back to places. |

|

| Media Cadena |

| Payne, 1818: The four exchange situations, in passing the gentlemen give their right hands to their partners, and the left to the other ladies. Four bars. |

Chivers, 1819: This is the same as the Half Right and Left . (4 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: half right and left. |

| Notes: see also the Cadena figure. |

|

| Media Engano |

| Chivers, 1819: is, that the first couple sets to the second, and turns the third. (8 bars.) |

| Notes: see also the Engano figure. |

|

| Molino |

| Lowe, 1831: (a mill,) cross hands, and back again. |

|

| Monas |

| Lowe, 1831: (monkies,) four form a serpentine line, as in La Poule, and set, looking at each other below the arms. |

| Notes: see also the Mono figure. |

|

| Mono |

| Payne, 1818: To perform this figure, the four join hands, the two gentlemen with their right hands, turn the ladies in the centre, so as to face each other and face their partners, forming a line, when the figure commences from the top and the left hands, when from the bottom, the gentlemen then turn the ladies back again to their places, this occupies Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: (or Serpentine Line), is performed by the two gentlemen turning the ladies in the centre, forming a line; then the gentlemen turn their partners to places. (8 bars.) |

| Notes: see also the Monas figure. |

|

| Paseo |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman takes the lady by one hand and leads her down the middle, the same back again, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is to lead down the middle, and back again, (8 bars.) This figure may be performed either by leading with one hand, or by Waltzing; the latter is more generally done. |

| Lowe, 1831: (a walk or walking-place), down the middle and up-again. |

|

| Paseo sostenida |

| Lowe, 1831: the couple joined, as in sostenida; go down the middle, and up again. |

|

| Paseo Trionfa / Paseo en trionfa |

| Payne, 1818: The gentleman and his partner and an other lady leads down the middle, the same back again, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is performed by three leading down the middle, and back again, in triumph. (8 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: is performed by three leading down the middle, and back again in triumph. |

|

| Pilota / Pilotas |

| Payne, 1818: The four join hands, advance, retire, and the gentlemen change places with their partners, advance, retire again and change places with the ladies on the sides, advance, retire again and change places with your partners, advance, retire and change places with the ladies on the sides, the four finishing in their original places, Sixteen bars. This is the only Spanish Figure generally known, it is performed various ways, and by many termed the Guracha, being often danced to a Spanish Tune of that name. |

| Chivers, 1819: is performed by all four setting, and change places with partners; then set and change places at the sides; then you meet your partners, set and change places with them, set and change places at the sides. (16 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (pilots,) four set and change places, on the sides of the dance; set again, and change places with partners; again, and change on the sides; and again, and change with partners, which brings all four to original places. |

|

| Retorno |

| Lowe, 1831: return to places. |

|

| Rueda |

| Payne, 1818: The four join hands and wheel round, Eight bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is hands four round and back again. (8 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (a wheel), hands four round, and back again. |

|

| Rueda barrilete |

| Lowe, 1831: the four move round in a circle, doing the waltz step singly. |

|

| Rueda fixado |

| Lowe, 1831: (a fixed wheel,) set with hands joined in a circle. |

|

| Sostenida |

| Lowe, 1831: (to sustain or support,) the Gentleman puts his hand behind the Lady's back, while she rests her arm on his. |

|

| Tornillo / Tornilla |

| Payne, 1818: Turn your partner or the other lady, Four bars. |

| Chivers, 1819: is to turn your partner, with both hands (4 bars.) |

| Lowe, 1831: (a little turn), turn your partners with both hands. |

|

| Triunfa |

| Lowe, 1831: (triumph,) the Lady crosses her arms in front, giving her right to the Gentleman on her left side, and her left to the Gentleman on her right; the Gentlemen join their other hands over her head, making a triumphal arch. |

|

| Waltze / Valse |

| Chivers, 1819: means for the first and second couples to pousette. |

| Lowe, 1831: or Valza, (waltz), the same as pousette, performed by one couple waltzing round the others. |

|

Many of the figures are recognisable either as standard English Country Dancing figures or as Quadrille dancing figures; the Spanish Country Dance can be seen as a combination of the two dance styles.

The extent to which these figures match the repertoire of the Spanish Contradanza is uncertain (at least to me) but one of the figures is especially curious: the Paseo Trionfa figure is very clearly related to the figure known in English as leading in triumph. This figure entered the repertoire of English Country Dancing either in 1792 or early 1793, we've written about it in a previous paper. If that figure is of English origin, and if the Spanish figures are of genuine Spanish derivation then the Triumph figure must have transitioned from England to Spain relatively recently. Conversely the English figure could have arrived from Spain (or elsewhere) in 1792. Either way, if there is a legitimate Spanish origin for the Spanish Country Dance as known in London then there must have been an active cross-pollination of ideas over the preceding 20 or so years. This lends credence to the idea that the British troops in Spain may have influenced the evolution of the Spanish Country Dance, perhaps taking the Triumph figure to Portugal and Spain with them.

Furthermore, if it can be shown that the Spanish Country Dance is of genuine Spanish derivation (rather than a c.1816 invention of Payne's) then that has implications for the origin of the Waltz Country Dance. The Waltz Country Dance is a dance form that Thomas Wilson claimed to have personally invented in 1815, that claim is disputable but he was certainly prominent in promoting the dance in London. Given the significance of Waltz steps and rhythms to the Spanish Country Dance it seems reasonable to suspect a Spanish influence to Wilson's work. Perhaps, for example, Wilson's swing corners a-la waltz figure should be understood as an allemanda sostenida figure, and his pousette a-la waltz figure as a Waltze figure. It's easier to believe that the Waltz Country Dance evolved in Spain over perhaps a couple of decades than that a single dancing master in London invented it within a single season.

Example Choreographies

Several British publications were issued containing example choreographies for Spanish Country Dances, we'll review those I've encountered here. Payne published six examples in his 1817 first set of Dances Espagnol and six more in his 1817 Second Set of Danses Espagnoles. Nathaniel Gow published one example in Edinburgh in his c.1817 #1 New Set of Quadrilles, Waltzes & Spanish Country Dances, it was published in English without reference to Spanish terminology. All twelve of Payne's choreographies were then repeated in Payne's 1818 Instructions for Spanish Dancing. Chivers published several further examples in his 1819 Recueil de Danses Espagnoles, he offered several written in English and several more in Spanish. At least two further collections were published c.1820, one by Wheatstone & Co. and the other in Liverpool by Hime & Son. The figures in the Wheatstone collection are closely related to those published by Payne, they either duplicate Payne's sequences or offer minor variations on a Payne choreography; the Hime choreographies are different and may be of a slightly later date, perhaps having been influenced by the Lowe publication. Chivers published his Dancers' Guide in 1821 and his Modern Dancing Master in 1822, much of the content for these works derived from his earlier publications, some new choreographies for Spanish Country Dancing can be found therein.

The table below documents the choreographies that I've encountered that were published in Britain using Spanish terminology between about 1817 and 1822. Those that are only available in English translation are not listed.

| Music | Dance |

|---|

Payne's 1817 Dances Espagnol |

| Danse Espagnol 1, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | The two first Couple Paseo, Media Cadena at bottom, then up again and the same at top, Monas, Engano, Rueda with the bottom Couple and *Waltz with the top.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

| Danse Espagnol 2, 6/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Cadena, Allemanda entera, Paseo, Pilota and *Waltz.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

| Danse Espagnol 3, 6/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains | Figure Barrilete behind the second and third Couples, the Gentleman Tornillo at top and the Lady at bottom and pass under Arcos made by the second and third Couples, Frentes and Tornillo with your partner, the same repeated, the two first Couple Paseo, Media Cadena at bottom, then up again and the same at top, and *Waltz.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

| Danse Espagnol 4, 2/4 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains, 1 16 bar strain, with D.C. | Latigo, Media Cadena, the same repeated, Paseo, Rueda with the third Couple, Espejos, with the second Couple and *Waltz.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

| Danse Espagnol 5, 6/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Favorita, Allemanda Sostenida, Paseo Trionfa, Monas, and *Waltz.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

| Danse Espagnol 6, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | The first and second Couples Frentes and Tornillo with their partners, Media Cadena, the same repeated, Pilota, Paseo, and *Waltz.

* This Figure may be omitted by playing the last part only once over.

|

Payne's 1817 Second Set of Danses Espagnoles |

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 1, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 1. Single Figure: Paseo, the first and second couple frentis and tornillo with their partners media cadena the same repeated.

|

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 2, 6/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 2. Single Figure: Monas, Paseo, and rueda with the bottom couple. |

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 3, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 3. Single Figure: Favorita, paseo trionfa, frentis and tornillo with your partner, the same repeated. |

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 4, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 4. Single Figure: The two first couples paseo, media cadena at bottom, then up again the same at top, and Engano. |

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 5, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 5. Single Figure: Latigo media cadena, the same repeated, allemanda entera with your partner and, the same repeated. |

| 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 6, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains, with D.C. | Double Figure: see Danse Espagnol 6. Single Figure: Paseo and espejos double. |

Chivers' 1819 Recueil de Danses Espagnoles |

| The Fancy / Mr Chiver's Fancy, 6/8 signature, 1 8 bar strain, 1 16 bar strain | Mono, Paseo, Waltze (3 parts, 24 bars).

|

| The Favourite / Mrs Chivers Favorite Waltz, 3/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains, 1 16 bar strain | Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Paseo, Waltz, Pilota (6 parts, 48 bars).

|

| The Insurgents, 6/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains | Pilota, Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Media Engano, Waltze (6 parts, 48 bars).

|

| St Quinton, 3/8 signature, 1 repeated 8 bar strain and 1 unrepeated 8 bar strain [the tune can be found in Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master] | Rueda, Paseo, Espejos (3 parts, 24 bars).

|

| Figaro, 6/8 signature, 3 8 bar strains and D.C. [the tune can be found in Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master] | Favorita, Paseo Trionfa, Mono, Waltze, Frentis, Tornillo (5 parts, 40 bars).

|

| The Regent, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains [the tune can be found in Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master] | See Danse Espagnol 2 (6 parts, 48 bars).

|

| The Nymph, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains [the tune can be found in Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master] | Cadena, Media Engano, Frentis, Tornillo (3 parts, 24 bars).

|

| Capt Swinton's Favorite Waltz, 3/8 signature, 2 8 bar strains with D.C. | Latigo, Waltz.

|

| The Little Waltz, 3/8 signature, 2 8 bar strains | Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Passeo, Waltz.

|

| The Patriot's Waltz, 3/8 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains | Cadena, Paseo, Allemanda Entera, Espejos, Pilota.

|

| The Little Nymph, 6/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains and 1 unrepeated 8 bar strain | Cadena, Media Engano, Allemanda Sostenida, Frentis, Tornillo.

|

| The Delight, 2/4 signature, 3 8 bar strains with D.C. | Favorita, Paseo Trionfa, Waltze, Allemanda Sostenida.

|

Wheatstone's 1820 No 1 of Spanish Dances |

| El Duca de San Carlos, 2/4 signature, 3 8 bar strains with D.C. | Paseo, Media cadena at bottom, Paseo, Media cadena at top, and Engano.

|

| L'Escurial, 2/4 signature, 3 8 bar strains with D.C. | See Danse Espagnol 4.

|

| El Maestro de Ceremonias, 6/8 signature, 3 8 bar strains with D.C. | See Danse Espagnol 2.

|

| Las Abas de Vittoria, 2/4 signature, 3 8 bar strains with D.C. | Barilete, Tornillo, Arcos.

|

| La Danca de Sevilla, 2/4 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains and 1 unrepeated 8 bar strain with D.C. | See 2nd Set Danse Espagnol 1 (single figure).

|

Hime & Son's c.1820 Spanish Dances or Danses Espagnoles |

| Armonia, 2/4 signature, 1 repeated 8 bar strain and 4 unprepeated 8 bars strains | Figura Barrilete, Arcos, Cadena, Media Espejos.

|

| Edmondo, 3/4 signature, 1 8 bar strain, 1 16 bar strain and 1 more 8 bar strain | The first and second Couples Frentes, and Tornillo with their Partners, Espejos Entera, Media Waltz with second Couple, Allemanda Entera.

|

| Carlota, 2/4 signature, 4 8 bar strains | Cast off one Couple and Frentes, Allemanda Entera, Favorita.

|

| Ironico, 3/4 signature, 2 12 bar strains | First and second Couple Frentes with Bolero Step, and Paseo one Couple, Allemanda Sostenida.

|

| Favorito, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains and D.C. | The two first Couple Passio, Media Cadena at bottom, then up again and the same at top. Monas, Engano, Rueda with the bottom Couple and Waltz with the top.

|

| Guaracia, 3/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains and D.C. | Pilota Entera, the first Gentleman with his Partner and Lady on his left Pasio Trionfa.

|

Chivers' 1821 Dancers' Guide [omitting those duplicated from his 1819 Recueil] |

| Mrs Chivers Favorite Waltz, 3/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains, 1 16 bar strain [see also Chivers' 1819 Mrs Chivers Favorite Waltz] | Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Paseo, Waltz (4 parts, 32 bars).

|

| St Quinton, 3/8 signature, 1 repeated 8 bar strain and 1 unrepeated 8 bar strain [see also Chivers' 1819 St Quinton] | Frentis, Tornillo, Media Engano, Cadena.

|

Chivers' 1822 Modern Dancing Master [omitting those duplicated from his 1819 Recueil] |

| Ferdinand VII, 2/4 signature, 3 8 bar strains [the figures can also be found in Chivers' 1819 Recueil in English] | Cadena, Paseo, Waltze.

|

| St Quinton, 3/8 signature, 1 repeated 8 bar strain and 1 unrepeated 8 bar strain [see also Chivers' 1819 St Quinton and 1821 St Quinton] | Pilota, Media Cadena, Tornillo.

|

| Capt Swinton's Favorite Waltz, 3/8 signature, 2 8 bar strains with D.C. [see also Chivers' 1819 Capt Swinton's Favorite Waltz] | Pilota, Waltz.

|

| The Cypress Wreath, or The Nymph, 6/8 signature, 2 8 bar strains with D.C. | Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Waltze.

|

| Bernadotte, or The Troubadour, 6/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains | Cadena, Media Engano, Paseo, Waltze.

|

| Isabella, or The Sun Flower, 6/8 signature, 2 repeated 8 bar strains | Favorita, Paseo Trinofa, Frentis, Tornillo, Waltze.

|

| The Young Prince, or Figaro, 6/8 signature, 3 8 bar strain with D.C. [see also Chivers' 1819 Figaro] | Cadena, Favorita, Paseo Trionfa, Rueda, Frentis, Tornillo.

|

| Don Carlos, 6/8 signature, 3 8 bar strains | Rueda, Latigo, Media Cadena, Waltze.

|

| The Regent, 2/4 signature, 3 repeated 8 bar strains [see also Chivers' 1819 The Regent] | Pilota, Latigo, Media Cadena, Latigo, Media Cadena, Paseo, Waltze.

|

It's unknown how widely any of these choreographies were danced; with the exception of the Guaracha it's likely that many of them weren't known outside of their creator's academy. The collections issued by Wheatstone and Hime (both of whom were music sellers) are interesting, they offer some assurance of a market existing for the dances c.1820, though perhaps only a small market. As best as I can tell these dances were considered to be novelties when first published, they experienced nothing like the meteoric success of the Quadrille.

Spanish Contradanza around the World

Figure 8. La Dança de Sevilla, an example Spanish Country Dance from Wheatstone's 1820 No 1 of Spanish Dances.

So far we've investigated the concept of Spanish Country Dancing as experienced in London and as taught by such English dancing masters as Edward Payne and George Chivers. We'll now consider the extent to which this dance style related to the dance experience of the Spanish speaking world. In so doing I must emphasise that I know little to nothing of genuine Spanish dancing at around our date, we'll instead consider the descriptions of such dancing in British sources of the appropriate date range.

It seems very probable to me that the Spanish Country Dance as experienced in London genuinely was inspired by the dancing of Spain; the terminology was offered in Spanish and the stylistic movements of the dance are consistent with what little I know of Spanish dance. For example, John Carr wrote in his 1811 Descriptive Travels in the Southern and Eastern Parts of Spain and the Balearic Isles, in the year 1809 that I had an opportunity of witnessing the decisive superiority of the Spanish over the English country dances. The former is slow, and combines the character of the waltz with the figure of the latter. . Carr's description of Spanish Country Dances is consistent with that of Payne and Chivers, albeit lacking in detail. Carr was writing of a ball held in Cadiz by the British naval commander on board his ship in 1809, the Spaniards evidently danced with a characteristic style. A passing reference to Spanish Country Dancing prior to the 1812 Battle of Salamanca can be found in the 1829 United Service Magazine; it recorded of a Military Ball thrown by the British officers at Rueda that It was extremely pleasant, with waltzing and all the fascinating mazes of the Spanish country-dance in perfection. Many of the Duke's staff attended. . Although brief this passage does emphasise that the British officers were encountering a distinctive style of Spanish Country Dancing in Spain.

Another description of Spanish dancing by Captain Basil Hall can be found in his 1824 Extracts from a Journal written on the coasts of Chili, Peru, and Mexico, in the years 1820, 1821, 1822; he wrote in a passage dated 19th March 1821 of the dancing in Chili: ... it is quite impossible to describe the Spanish country dance, which bears no resemblance to anything in England. It consists of a great variety of complicated figures, affording infinite opportunities for the display of grace, and for showing elegance of figure to the greatest advantage. It is danced to waltz tunes, played in rather slow time; and, instead of one or two couples dancing at once, the whole of the set, from end to end, is in motion. No dance can be more beautiful to look at, or more bewitching to be engaged in . Hall was writing a decade or more after Carr, and from a different continent, but once again the description of the Spanish dancing is highly consistent with that of Payne and Chivers. It's perhaps notable that Hall described the Chilean longways dancing as involving everyone moving simultaneously; modern enthusiasts may expect the same to be true of English Country Dancing, 200 years ago most dancers in an English longways set had to wait until the top couple reached them before they were absorbed into the dance.

A slightly different description of Spanish dancing was offered by Charles Stuart Cochrane in his 1825 Journal of a residence and travels in Colombia during the years 1823 and 1824; Cochrane wrote of a Ball hosted by the Vice President of Colombia in Bogota: By some the Spanish country-dance is considered as well adapted to a warm climate; but I think it inferior to quadrilles, both in grace and comfort. In the former, elegance can only be shown in the twisting and twining of the arms and body; and then at a large party you are so crowded, that grace in this particular cannot be observed; you are likewise constantly in masses together, and never for a moment allowed to stand still, which causes for greater heat to be felt than in the graceful movements of a quadrille, where you are allowed more space, and time for rest and conversation. Spanish country-dances and waltzes were the order of the night ... When you are engaged to dance, on the music commencing, you go and take your place in the dance, and when the whole line of men is formed, the young ladies rise and go to them. This prevents any one going unfairly above another, as no man will allow any intruder to come above him, since he acts for the lady; and no one is allowed to sit down until the dance is finished: this is quite proper, but very fatiguing, as sometimes a country-dance will last an hour. . Cochrane implied, just as we saw from Hall, that all of the dancers would be in motion all of the time. A single dance might last upwards of an hour, just as it might in Britain at this date, but as everyone was permanently in motion it wasn't just the leading couple who were liable to be exhausted by the end.

None of these descriptions of Spanish country dancing hints that the leading couples would begin dancing improper, that could perhaps have been Payne's own invention; but the stylistic characteristics of the London dance do appear consistent with those of the Spanish speaking world. Indeed, the English commentaries of Payne and Chivers may have done more to record the genuine figures of the Spanish contradanza and cuadrilla than did the Spanish speaking dancing masters themselves!

Legacy of the Spanish Country Dance

We've seen that the Spanish Country Dance became known in Britain from around the year 1816, it was initially promoted by Edward Payne then subsequently by G.M.S. Chivers and others. 1816 was an interesting year in the British Ball Room, the Waltz was increasingly danced, the Quadrille was experiencing a dramatic increase in popularity and the traditional English Country Dance was experiencing a sharp decline.

Those dancing masters in London who relied on advertisements in order to reach potential clients reacted accordingly. They promoted new dance formats often of their own invention, Payne's Spanish Country Dance and Wilson's Waltz Country Dance seem to have triggered an arms race of sorts! The following few years would see the invention of the Ecossoises (1817), Swedish Country Dances (1818), Circular Country Dances (1818), Quadrille Country Dances (1819), The Mescolanze (1819), Mescolanze Quadrilles c.1819, L'Unions (1821), Chivonian Circles (c.1822), Circassian Circles (c.1822)... and so forth. None of these dance formats were immediately successful, at least in London, but they were often picked up and taught by provincial dancing masters who (perhaps mistakenly) thought they were successful dances from London, and so over the decades they would indeed become more generally known. Many of these formats survive today despite failing to invade the ballrooms of the nobility when first published.

The Spanish Country Dance had a little more success, at least initially, than most of these other dance novelties. We've seen that at least two music publishers sold collections of Spanish Country Dances c.1820, evidence also exists that they were danced at Almack's Assembly Rooms (the most prestigious dancing venue in London). The anonymous author of the 1823 The Etiquette of the Ball-Room by A Gentleman briefly mentioned that Espagnoles, or Spanish Dances, and Polonaises, have been introduced at Almack's, and are very interesting, pleasing, and easy elegeant Dances, chiefly confined to a Waltz system; which places them far above common Contre Dances, and may be learned in a very short time . There are occasional references to Spanish Country Dances being experienced in Britain throughout the 1820s, for example the Brighton Gazette for the 17th January 1828 reported of a ball at Tunbridge Wells at which Quadrilles, waltzing, Spanish country dances, and polonaises, were the order of the evening . But over time the Spanish Country Dance seems to have devolved from a distinct class of dance in Britain to being little more than just the Guaracha dance that we described above (see also Figure 9).

It seems increasingly probable that the dance trends of Spain influenced the development of the Waltz Country Dance in Britain; if so then that's a far more significant legacy - the fusion of waltz rhythms with country dancing figures remains a popular element of the country dancing experience today, both in Britain and around the world.

We'll leave this investigation there; if you have anything further to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Figure 1. Detail from Davidson's 1856 Pop Goes the Weasel, The Spanish, & Forty Other Country Dances. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library. The form of this dance is similar to that of a Spanish Country Dance of our period, though not exactly the same.

Figure 1. Detail from Davidson's 1856 Pop Goes the Weasel, The Spanish, & Forty Other Country Dances. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library. The form of this dance is similar to that of a Spanish Country Dance of our period, though not exactly the same.

Figure 8. La Dança de Sevilla, an example Spanish Country Dance from Wheatstone's 1820 No 1 of Spanish Dances.

Figure 8. La Dança de Sevilla, an example Spanish Country Dance from Wheatstone's 1820 No 1 of Spanish Dances.

Figure 9. Spanish Dance from William De Garmo's The Dance of Society, New York, 1875.

Figure 9. Spanish Dance from William De Garmo's The Dance of Society, New York, 1875.