English Regency Dances, Costumes, Balls, Etiquette, Lessons and Music

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

| Return to Index |

|

Paper 53 Exotic English Country Dances of the late 18th CenturyContributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 3rd November 2021, Last Changed - 2nd April 2022]Most of the English Country Dances published in Britain in the 18th Century followed a reasonably consistent formula, a tiny minority however were genuinely different. In this paper we'll review some of those unusual and exotic Country Dances of the late 18th Century that defied the trends. Together these dances hint at a slightly more diverse social dancing experience having existed in the past than might otherwise be thought, some dancers were evidently willing to experiment.  Figure 1. William Hogarth's c.1745 The Country Dance, part of an unfinished series about a happy marriage.

Figure 1. William Hogarth's c.1745 The Country Dance, part of an unfinished series about a happy marriage.

The dances we'll consider further in this paper are:

Typical Country Dances of the late 18th Century

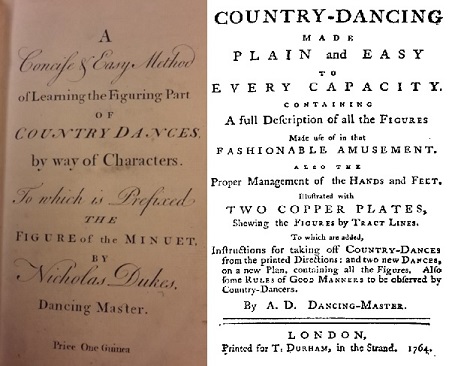

We should first consider what was conventional in the Country Dancing industry of the 18th Century, we can then go on to consider what was atypical and unusual. Most of what we know of Country Dancing prior to the the 18th Century derives from study of the Country Dance publications of John Playford (1623-c.1686). Playford, and his successors, issued some 18 editions of a book named The English Dancing Master (later simply The Dancing Master) between 1651 and around 1728. Each new edition would see new dances added and some of the older dances removed. Early editions included a greater variety of dance forms than the later editions, this included square dances, non-progressive dances and round dances. As time went by the dance form simplified into the ubiquitous The mid 18th Century also saw the publication of two important books about Country Dancing, these two works are incredibly important to the modern study of Country Dancing, they offer a fascinating wealth of detail beyond what can be gleaned from the published dances themselves. These two important books were the 1752 A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes (see Figure 2, left) and the 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by an anonymous dancing master who published under the initials A.D. (see Figure 2, right). It's unlikely that either work was influential when first published, they probably enjoyed a small and localised readership, their value to modern scholarship is tremendous however. They enable modern readers to analyse dances published in the mid 18th Century and reconstruct them using authoritative supporting information. Both works attempted to document Country Dancing of their respective dates in an encyclopedic level of detail; neither achieved that (as a modern reader significant questions remain unanswered) but if we want to reconstruct historical dances as they'd have been understood when first published then these works help enormously.

Nicholas Dukes was a dancing master based in  Figure 2. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes, 1752 (left) and Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D., 1764 (right).

Figure 2. A Concise & Easy Method of Learning the Figuring Part of Country Dances by Nicholas Dukes, 1752 (left) and Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy by A.D., 1764 (right).

Grown Gentlemen or Ladies may be taught a Minuet, or the Method of Country Dances, with the modern Method of Footing, in so private, genteel and expeditious a Manner, as to render them very soon capable of performing in the politest Assemblies. Mondays and Wednesdays being the Nights for practising of Country Dances, there's a compleat Set of Gentlemen only, which assembles for that Purpose. Nicholas Dukes wrote principally of the figures used in Country Dancing, he also advocated that anyone with pretensions to gentility first master the Minuet before learning the Country Dance. The elegance required of the Minuet would serve the dancer well within a Country Dance. He wrote very little on the form of the Country Dance however, most of his effort was invested in describing the figures.

A.D. also wrote of the figures used in Country Dancing but went further and also wrote of the form, style and etiquette of Country Dancing. The

What we read in the works of Dukes and A.D. is consistent with what can be found in the typical Country Dance collections of the period. People in general were dancing longways sets ( If we consider the early 19th century then several new variations in Country Dancing would go on to be documented, some more popular than others. Examples include the Waltz Country Dance, the Spanish Country Dance and a range of hybrid dances including Ecossoises, Swedish Country Dances and Circular Country Dances. These 19th Century innovations offer evidence that dancing masters, at that time, were willing to experiment with the general form of the Country Dance. It seems likely that this had always been true and that dancing masters of earlier decades were equally willing to experiment, we simply have more evidence to draw upon at later dates. This paper will consider some of the more peculiar Country Dances from the later 18th Century that were in fact published, thereby offering some supporting evidence in favour of the diversity theory. We will now consider some examples of convention defying dances.

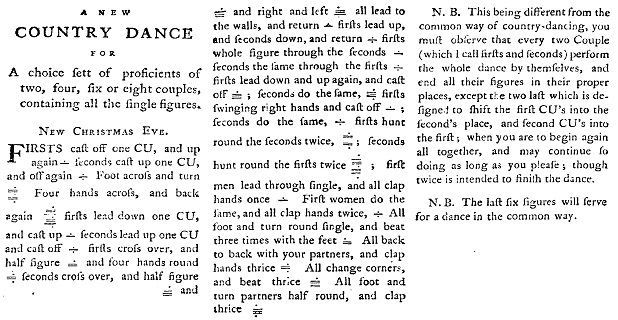

Figure 3. New Christmas Eve from A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy.

Figure 3. New Christmas Eve from A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy.

A.D.'s New Country Dances, 1764 (Complex 2 and 3 couple sets)

The first of the Country Dancing novelties that we'll study are actually found towards the back of A.D.'s 1764 Country Dancing Made Plain and Easy. Two Country Dances were published there, together with their music, which are unlike any I've seen published anywhere else. The first was named New Christmas Eve (see Figure 3) and was described as

The dances are, to say the least, challenging. They're described as being for

New Christmas Eve is a dance for two couples, or a multiple thereof. The instructions note that

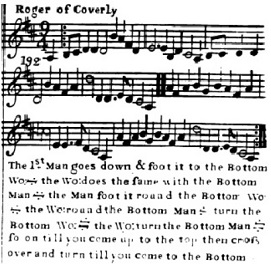

This concept extends to New Twelfth Night where  Figure 4. Roger of Coverly from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2

Figure 4. Roger of Coverly from Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2

My suspicion is that these dances were used by A.D. when teaching country dancing in person. Perhaps the figures would be announced by a prompter (in the modern sense where figures are called out mid-dance) and the scholars would perform what they heard. It seems improbable that they could be used in any other context. They're a fascinating insight into the liberties that might be taken with the form of the Country Dance by a professional dancing master, especially in the privacy of their own academy.

Roger of Coverly, c.1764+ (A stretched Country Dance)Sir Roger de Coverly is a unique dance that we've written about before. We'll not repeat most of that information here, you might like to follow the link to read more. The music for Roger dates back to the end of the 17th Century, an important innovation was published c.1764 however, that's what causes the dance to be included within our list here.

At some point during the 18th Century a unique dance came to be associated with the tune, the earliest variant of which (as far as I know) was published in Thompson's c.1764 Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances, Vol 2 (see Figure 4). The figures for this dance defied the standard conventions for a Country Dance; normal Country Dances restricted the dancing to a The dance went on to be republished many times over in several distinct variations. One early 19th Century publication advised that the strains of music should be played in a loop until the dancers have interacted with everybody in the set (that is, the musicians must watch the dancers and change what they're playing only when the dancers are ready). If that advise were followed then it would make for a unique experience.

The dance would continue to evolve over the late 18th and early 19th centuries, it would become referred to as a

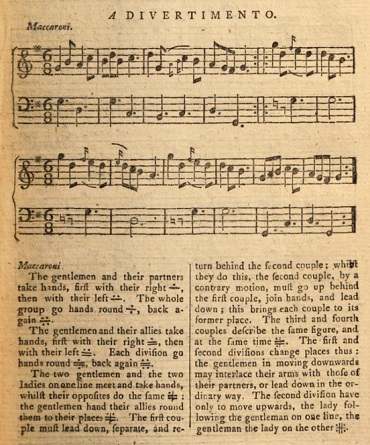

F.P.'s Divertimentos, 1772 (Becket formation Country Dances)The next dances we'll consider were published in 1772 by another anonymous dancing master, this time under the initials F.P.. It's quite possible that F.P. was in fact the Scottish dancing master Francis Peacock (1723-1807), Peacock would go on to publish an especially important book named Sketches Relative to the History and Theory, but More Especially to the Practice of Dancing in 1805. Any such identification remains speculative however.  Figure 5. Maccaroni by F.P. in The Lady's Magazine, Vol III for the Year 1772.

Figure 5. Maccaroni by F.P. in The Lady's Magazine, Vol III for the Year 1772.

F.P.'s dances of 1772 were named

F.P. explained in a letter to the editor that

Readers may have noticed that the dance described does not follow the typical pattern of a modern Becket formation Country Dance. A typical 20th century Becket would have partners stood side by side (in the position F.P. described as being that of the

F.P. acknowledged that the dance form could be confusing: I've no evidence of these Divertimento dances being enjoyed socially, or even of further examples being published. They seem rather to have been an experiment that F.P. hoped that someone somewhere might enjoy. They do however offer evidence that there were dancing masters prepared to be creative with the form of the country dance in the 1770s.

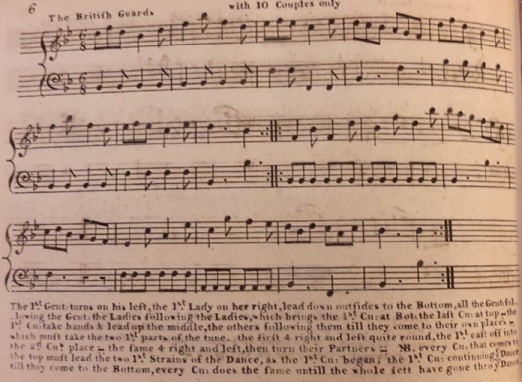

Fishar's British Guards, 1778 (A 10 couple dance)Our next dance is another oddity, this time published by James Fishar in his 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets. It's a County Dance that was arranged specifically for ten couples and was named The British Guards (see Figure 6). The publication date for the collection wasn't included on the cover of the work, it can however be dated to 1778 as Fishar advertised the collection as being new in The General Advertiser for the 5th of March 1778. That advertisement is rather interesting and so is reproduced here in full, it reads:  Figure 6. The British Guards by James Fishar from his 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.b.(4.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 6. The British Guards by James Fishar from his 1778 Twelve New Country Dances, Six New Cotillons and Twelve New Minuets. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.9.b.(4.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Now are published, Twelve new Country Dances, with Six Cotillions, calculated on purpose for those ladies and gentlemen who do not understand the steps. The music composed, and the figures adapted by James Fishar, for ten years first dancer, ballet-master, and head teacher of all the dancing at the King's Theatre, London. To which is added, Twelve new Minuets: the whole with a thorough bass for the harpsichord. Mr Fishar, being convinced that many ladies and gentlemen do not like to dance cotillions, on account of being obliged to learn the steps. Mr Fishar thought himself bound in gratitude for the many favours he has always received from the public, both in his capacity of first dancer, ballet-master, and in all his publications, to find out a method for them to dance now those kind of dances, without any steps but the common country dance steps, which nobody has attempted before; and if this meets with their approbation, he will not spare pains nor trouble to furnish them every year with a new set of them, so easy as to be understood at one view. Price two shillings and six-pence. To be had of Mr Rutherford, at his music shop in St. Martin's-lane; and all the music shops in London.

The collection of dances was issued by one of the most prominent dancers in London, Fishar claimed to have paid great care and attention to their creation and had simplified them to be of use to even the least proficient of dancers. He went so far as to claim that the Country Dances in the collection (which would include The British Guards) were

The British Guards is unusual principally because it is arranged to be danced The dance is somewhat similar to Sir Roger in that all the couples in the entire Set are involved in each iteration of the dance. This is in stark contrast to the many thousands of other Country Dances that were published and which restricted the dancing to a minor set of either two of three couples. It demonstrates once again that some dancing masters were willing to experiment with the form of the Country Dance. Fishar evidently did so in a collection he aimed at the least sophisticated of dancers.

Le Boulanger, c.1780+ (A round dance)It's debatable whether our next dance should be considered to be a variation of the English Country Dance at all, it was sufficiently different to almost any other dance that it might be considered a unique dance form in its own right. Its name is Le Boulanger, it's a dance that we've written about elsewhere, you might like to follow the link to read more. The earliest known versions of this dance were published in Paris, perhaps as early as 1740, it is an unusual French Country Dance. At least two dances named Le Boulanger were published in London c.1780, one by Thomas Budd and the other by Francis Werner. I don't have a copy of Budd's publication to refer to, Werner's dance was really quite interesting though. Werner's directions indicate that any number of couples may dance it, they were to form a circle (standing side-by-side, as in a Cotillion). The dance starts with everyone circling around and back again; this is followed by a sequence of turns in which the first man alternately turns the next lady in the circle, then his parter, all the way around the circle. Everyone then circles again, followed by the first lady alternately turning each man and her partner around the circle. Each couple repeats this sequence around the entire circle. This is another dance that would go on to be even more successful later in the century, it would go on to be a favourite dance in Regency London. As with Sir Roger de Coverly it's a dance that caused all of the dancers to interact with each other, it also ensured activity for each dancer in every iteration of the dance. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Le Boulanger here.

Before moving on I'll quickly point out that other variations on the standard Cotillion or French Country Dance formations were also being danced in Britain. Examples include Cotillion dances arranged for just two couples (which were referred to as  Figure 7. The Caledonian Medley Dance by Thomas Skillern, 1787. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.e.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 7. The Caledonian Medley Dance by Thomas Skillern, 1787. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.49.e.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

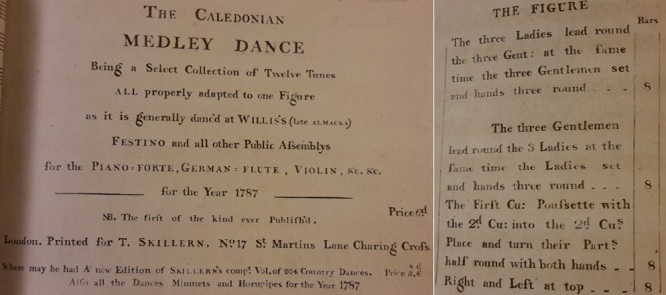

Skillern's Caledonian Medley Dance, 1787 (A medley of tunes for the same figures)

The next dance we'll consider is a simple Country Dance in an unusual musical arrangement, as published by Thomas Skillern in 1787. Skillern (d.1800) was one of London's music sellers, we've written about his nephew (also named Thomas Skillern) in another paper. He issued a unique publication named The Caledonian Medley Dance for the Year 1787 (see Figure 7) which documented our dance. He described the contents as

Skillern's implication was that he had documented the experience of dancing at the fashionable Assembly Rooms of his date. Most dance publications at this date would make a similar claim of course, Skillern's text could be considered hyperbole, it was more detailed than most however. Other publishers might claim that their works were

The next thing to note is that the collection was described as being a  Figure 8 The 1791 La Mêlange by James Platts

Figure 8 The 1791 La Mêlange by James Platts

The next thing to note is that the collection of tunes was described as being Medley dances may have been commonplace in late 18th Century London, it's difficult to know. This is the only publication I'm aware of to have attempted to document them (except for our next example below), any such convention may therefore have been isolated and of short duration. The implication that medleys were being danced at Almack's and the Festino gatherings at Hanover Square is fascinating, it hints once again that the social dancing conventions may have been more flexible than we might otherwise have imagined.

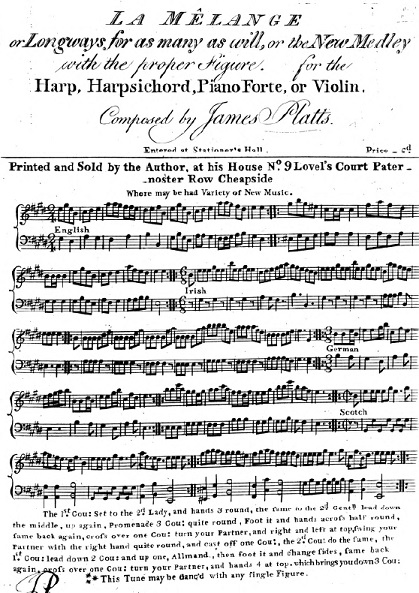

Platts's La Mêlange, 1791 (A triple progression medley)

Our next dance is a second example of a medley dance, this time arranged in a very different way to Skillern's example. It was published by James Platts as his 1791 La Mêlange single sheet publication (which was registered for copyright purposes at Stationer's Hall on the 2nd of January 1792, see Figure 8). We've written about James Platts (and this dance) in a previous paper, you might like to follow the link to read more. The work was subtitled

The Platts dance was once again arranged so that several different tunes would be played in immediate succession. Platts selected four tunes that he named as

Platts went further however. For his medley he choreographed a complicated set of figures that would extend over the entire musical sequence, each iteration of this dance would involve all four tunes in their various different time signatures. The result is somewhat reminiscent of A.D.'s New Twelfth Night above. The Platts arrangement is especially noteworthy for involving a triple progression of the leading couple, at the end of the four tunes they will be in the 4th position such that a new minor set can lead off behind them. It's very unusual to find a published Country Dance with more than a single progression arranged within it, on the rare occasions that they are encountered there's often an assumption of error; Platts leaves us in no doubt, he ended his figure sequence after a triple progression: This dance is complicated. That it was being sold as a stand-alone publication (rather than within a larger work) is fascinating, Platts must have thought there would be a market for this type of publication. It may have been an experimental work of course. Platts was operating at the leading edge of several new dance trends; for example, at this c.1790 date he was pioneering the use of Waltz rhythms in Country Dances (he published several examples before almost anyone else is known to have done so). His publications may have been popular amongst the more adventurous of London's social dancers. Once again we have found a clue that medley dances may have been danced in London towards the end of the 1780s and start of the 1790s, this time we also have clear evidence of multi-progression dances being experimented with too. We've animated a suggested arrangement of the dance in four parts: Part 1 (English), Part 2 (Irish), Part 3 (German), Part 4 (Scotch).

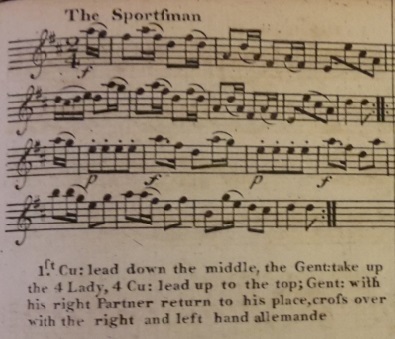

Metralcourt's The Sportsman, 1793 (A quadruple minor) Figure 9. The Sportsman by Charles Metralcourt from his 1793 Twenty Four Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(7.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9. The Sportsman by Charles Metralcourt from his 1793 Twenty Four Country Dances. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.(7.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Our next dance was published by Charles Metralcourt in his 1793 Twenty Four Country Dances, they were (according to the cover) One of the dances in the collection was a little unusual, it is named The Sportsman (see Figure 9). The rest of the collection was made up of a fairly typical set of Country Dances, The Sportsman only differs in so far as the dancing involved an unusual figure and a fourth couple. The thousands of other Country Dances published in our date range invariably involved either two or three couples in a minor set, this dance involved four. It could be argued that this dance was published with a typesetting error present and that it should have involved only three couples, it could certainly be danced with only three; but (as noted above) Metralcourt was an eminent dancing master and he dedicated his collection to the Prince of Wales, mistakes shouldn't have been made. The reference to a fourth couple appears twice within the text, if it was a misprint then the mistake occurred twice. The existence of this dance hints that the social dancers at the Bath Assembly Rooms would not have been concerned or surprised by a quadruple minor dance should it have been encountered, they would perform it just as easily as they would accept a slightly exotic dancing figure.

The exotic figure from this dance involves the leading couple dancing down the set and the man exchanging his partner for the fourth lady, he then returns to the top of the set with that new partner. The new

ConclusionLondon's Country Dance collections of the later 18th century tend to be formulaic, the dances were single progression duple or triple minors in a conventional arrangement. Dance historians often summarise this period as one of simplification. Much of the novelty to be experienced in Country Dancing was found in the seasonal cycle of new tunes becoming popular, not in the dance form itself. This paper has demonstrated that some dancers of the later 18th Century would have experienced novelty in the dance hall. Some dancing masters were willing to experiment with the format of the dance. The experience in the Assembly Rooms and Ballrooms of the nation would not have been universally the same, even though the bulk of the music publishing industry issued formulaic dance collections. That's not to suggest that there was a great degree of variety of course, the dances we've studied in this paper were exceptional, they don't disrupt the broader trends. What remains uncertain is the extent to which variety was encountered, perhaps variety tended not to be recorded?

One of the challenges when investigating an unusual historical Country Dance is the question of quality. If a Country Dance (as published) seems not to

If we were to consider the early 19th century then a greater variety of Country Dance variants would emerge, we've written about many of them before. Examples include Mr West of Derby who mentioned (Derby Mercury, 4th July 1805) his We'll leave the investigation there; if you have anything further to share then do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2024

All Rights Reserved