English Regency Dances, Costumes, Balls, Etiquette, Lessons and Music

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

| Return to Index |

|

Paper 40 Three Whitehall Balls of 1803Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 13th December 2019, Last Changed - 21st March 2022]Britain's nobility often owned palatial town houses in the city of London. In this paper we'll investigate three private balls held at two such homes in the Whitehall district of London in 1803. Two were hosted by the Honourable Mrs Robinson (in what was later known as Malmesbury House, a building subsequently demolished in the late 1930s) and one by the Duchess of Gordon (at Fife House, a building demolished in the 1860s). All three balls were described in London's newspapers in sufficient detail that we can recover a partial list of the dances. We'll see that several tunes were sufficiently popular in 1803 to have featured at more than one of these events.  Figure 1. Fife House seen from the River Thames, 1831 (top left); Constable's 1817 Opening of Waterloo Bridge seen from the garden of Fife House (bottom left); location of (1) Fife House and (2) Malmesbury House on the Horwood Map of 1792-9 (top right); and Malmesbury House in the 1920s (bottom right).

Figure 1. Fife House seen from the River Thames, 1831 (top left); Constable's 1817 Opening of Waterloo Bridge seen from the garden of Fife House (bottom left); location of (1) Fife House and (2) Malmesbury House on the Horwood Map of 1792-9 (top right); and Malmesbury House in the 1920s (bottom right).

The tunes and dances that we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

The Whitehall Balls

Whitehall is the district of London that had once been occupied by the magnificent and ancient Palace of Whitehall. The Tudor palace had burned to the ground in 1698 following an unfortunate laundry related Two of our 1803 balls were hosted by Catherine Robinson (1749-1834) at her prestigious address of No 8 Whitehall Gardens; she was the widow of the Honourable Frederick Robinson (1746-1792) and aunt to the future prime minister F.J. Robinson (1782-1859) (he would be briefly appointed to premiership in 1827). Her property was subsequently owned by her nephew the Earl of Malmesbury, after whom it was renamed. The property would continue to be known as Malmesbury House until it was demolished in the 1930s. Mrs Robinson didn't have an aristocratic title of her own but she was both rich and influential; she was an aunt to the Earls of Malmesbury, Morley, De Grey and Ripon.

Our third ball was hosted by Jane Gordon, Duchess of Gordon (1749-1812) at Fife House, the London home of James Duff, Earl of Fife (1729-1809). The two houses (the term

The Hon. Mrs Robinson's Ball, Thursday 24th March 1803 (First Ball)The following text describing our first ball is quoted from the Morning Post newspaper for the 26th March 1803, the dance references have been emphasised:  Figure 2. Dancers in a private home practising on carpet, 1817. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.

Figure 2. Dancers in a private home practising on carpet, 1817. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Library.

The above Lady, so well known in the circles of thehaut ton, invited on Thursday evening a small party of distinguished fashionables to alittle dance. The very elegant family mansion in Privy Gardens needed but few additional ornaments to render it worthy of its noble visitors, and those few were displayed in the Ball-room, which was elegantly adorned with brilliant lustres, candelabras, &c.. The dancing took place on the carpet (a system of economy introduced this season by the Countess of Malmsbury, who has given several balls upon the same plan). The party was a very early one; the greater proportion of the Ladies arrived at nine o'clock, an hour, nearly, before the Gentlemen. A short time having passed in conversation the spirited Lady Catherine Harris proposed to Miss Carnegie, that since the gentlemen were absent, it would not be amiss if they were to open the Ball: this was immediately assented to, and the music struck up Lady Anne Stuart, by desire, we believe, of Lady Mary Bentinck. After the lapse of a quarter of an hour, the regular dances commenced, when the following couples appeared:

Several anecdotal observations immediately emerge. It's notable, for example, that the dancing at this private Ball was conducted on carpet; our correspondent from 1803 was clearly surprised by this detail, hence it was recorded for posterity. The normal protocol for a ball was to remove any carpets, clean the floor, and then chalk or watercolour the wooden surface with artistic imagery. This was a time consuming and expensive undertaking, carpets were often nailed down and significant effort would be required to move them. We're informed that the Countess of Malmesbury (Mrs Robinson's sister-in-law) had recently pioneered a

We're also informed that the Gentlemen at this Ball were Our correspondent named several of the couples who danced together, in many cases these people can be identified. The named dancers are listed below with additional biographic details in parentheses:

Several observations might be made about the dancers. The host's nephew appears to have led off the first of the dances, it was a common convention for a relative of the host to do this. Most of the dancers were unmarried and the men tended to be a little older than the ladies. Several foreign dignitaries can be found amongst the dancers, they were members of the various ambassadorial delegations in London at the time.  Figure 3. Fashionable costumes of June 1803, including a diamond or pearl bandeau and feathers; courtesy of candicehern.com

Figure 3. Fashionable costumes of June 1803, including a diamond or pearl bandeau and feathers; courtesy of candicehern.com

The Hon. Mrs Robinson's Ball, Monday 18th April 1803 (Second Ball)The following text describing the second ball is taken from the Morning Post newspaper for the 20th April 1803, the dance references have again been emphasised: On Monday evening the above Lady gave a Ball and Supper, at her house in Privy Gardens, to about one hundred of the first-rate fashionables. The Ball-room was, as usual, illuminated in a very splendid manner, with chandeliers, &c.. As early as half after nine o'clock the ball was opened with Sir Charles Douglas, by Mr Sloane and Lady Maria Harris There are fewer anecdotes to comment upon in this text but one detail does stand out: the ball concluded at 3.30am. Most society balls were either conducted throughout the night, or would end around midnight thereby allowing the guests to attend a second event. If the ball ended at 3.30am then the guests would presumably have gone home at a relatively early hour.

Another interesting detail is that two of the tunes that we know were danced at the first Ball were reused at this event. The attendees at this ball consisted of around 100 The named dancers who took part in the first dance of this Ball were:

It appears that of the one hundred fashionables attending the ball fewer than twenty danced the first dance. This was a fairly common phenomenon; dancing at private balls, at least as reported in the newspapers, rarely involved more than 20 couples even though the total attendance might be in excess of 200 people.

The Duchess of Gordon's Ball, Monday 27th June 1803 (Third Ball)The following text describes our third ball, it is quoted from the Morning Post newspaper for the 29th June 1803, the dance references have once again been emphasised:  Figure 4. Savoyards of Fashion, 1799. Courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 4. Savoyards of Fashion, 1799. Courtesy of the British Museum.

One of the most splendid entertainments of the kind took place at Fife House, in Privy Gardens, on Monday evening. All the apartments were fitted up with all possible taste and splendour; those on the ground floor were appropriated for dancing, &c.. The grand eating-room, which fronts the river, was the ball-room, and the adjoining apartments were set apart for promenading. The grand hall, or principal entrance, was appropriated for serving out tea, and the dining-room for cards. Eleven tables were there set out, and whist was the favourite game. In every room, in the cells of every window, the hall, and around the outside of the house, were placed all kinds of flowering shrubs, of peculiar beauty and size, brought from the gardens of the Earl of Galloway's seat. Every apartment (about eight in number) was illuminated by chandeliers, and a vast number of chrystal lamps, the effect of which added much to the brilliancy of the scene; and in a marquee, placed in the garden, the band of Savoyards, from Vauxhall, were stationed during the early part of the night.

This ball featured a Hornpipe solo dance (as entertainment) and several country dances, a figure dance was almost inserted but it proved too much for the company. We're informed that the gentlemen in particular suffered exhaustion from the heat of the dancing, it was alleged to have been the The music for at least part of the evening was supplied by the Savoyard Band from Vauxhall Gardens, they were a popular French themed band. Other such bands of a similar nature at around the same date included the Maltese Band, the Pandean Band and the Silver Miners; the Savoyards were sufficiently popular to be referenced in the 1799 print seen in Figure 4; it satirises the leaders of fashion (tentatively identified by the British Museum to include the Duchess of Buckinghamshire and Lady Charlotte Campbell) by likening them to the Savoyard minstrels. The named dancers who took part in the first dance were:

Sixteen couples are identified as having danced at the Gordon ball, we're informed that as many as thirty couples were dancing in total. Dancing requires space, Fife House must have been large. The Robinson Balls, by way of comparison and as far as the evidence allows us to assume, involved perhaps 12 or fewer couples dancing. The named dancers at the Robinson and Gordon balls were different; the two hosts presumably moved in different social circles and had different pools of friends to invite; the exception to this observation being Lady Mary Bentinck who was present at both a Robinson ball and also at the Gordon ball. One dancer is of particular interest - Lady Madelina Sinclair. Madelina was a daughter of the Duchess of Gordon; her first husband had died in 1795 leaving her a widow; she was 31 years old at the date of our ball and led-off the dancing, she was reported to be We'll now consider each of the named tunes and dances from across our three Balls in turn.

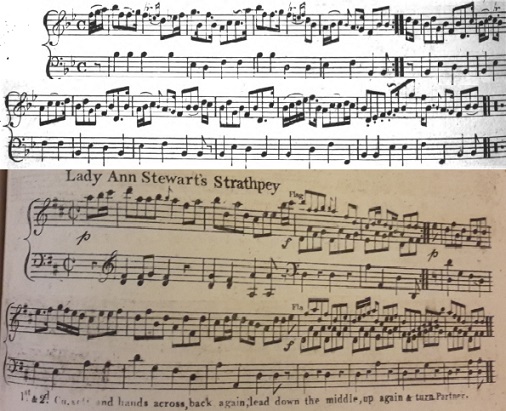

Figure 5. Lady Ann Stewart's Favorite Strathspey, from Nathaniel Gow's 1802 publication of the same name (top), and Lady Ann Stewart's Strathspey from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 5. Lady Ann Stewart's Favorite Strathspey, from Nathaniel Gow's 1802 publication of the same name (top), and Lady Ann Stewart's Strathspey from Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.64. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Lady Ann Stewart's Favorite Strathspeythe music struck up Lady Anne Stuart, by desire, we believe, of Lady Mary Bentinck(First Ball) The second dance, Lady Ann Stuart...(Second Ball) Numerous tunes had been published over the years with names that might perhaps be identified as our tune, luckily only one has any credibility as being the legitimate and popular tune (it has an impeccably relevant provenance as we'll see shortly). The tune from our Balls was composed by Nathaniel Gow and was first published in Edinburgh in 1802 in a minor work named Lady Ann Stewart's Favorite Strathspey (see Figure 5), this collection was advertised as having been published in mid 1802 (Caledonian Mercury, 10th June 1802). Gow republished the same tune many years later in his 1818 Part First of the Beauties of Niel Gow. Identifying Gow's dedicatee isn't quite as simple; she was probably Lady Anne Stewart (c.1742-1821), the widow (and cousin) of Sir John Stewart (c.1740-1797) 5th Baronet of Castlemilk, the identification is uncertain however as other viable candidates exist.

The tune seems not to have been widely published in London. It can be found in Charles Wheatstone's c.1804 2nd Number and also in Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book (first variant) (see Figure 5), I've not found it elsewhere. My archives are incomplete of course, further London publications may yet emerge, it's unusual for such a fashionable tune to be so under represented within the London publications (we'll go on to see further examples of this oddity amongst the subsequent dances). The prevalence of similarly named tunes may perhaps have confused the London publishers, it's possible that they weren't sure which tune was being danced at our society balls; for example, another tune named Lady Mary Stuart was also being danced socially in 1803, some publishers may have wrongly assumed that they were the same tune. Lady Mary Stuart was more frequently published in London than was Lady Ann Stewart, the two tunes are quite different but the public may have been unaware of this confusion.

Our tune was known in London in 1802 even if it was yet to be published there. It was danced at Marchioness Headfort's Ball (Morning Post, 26th May 1802) where In addition to featuring at our two Robinson balls of 1803 the tune was also danced at Lady Saltoun's Ball (Morning Post, 24th March 1803) and at Lady Mildmay's Ball (Morning Post, 22nd April 1803). It was danced at The Ladies Townshend and Miss Fulekers Ball in 1804 (Morning Post, 7th May 1804) and at a Ramsgate ball of 1805 (Morning Post, 18th September 1805). I've not located any further social references to the tune thereafter, it was clearly a favourite but perhaps for just a few years. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Charles Wheatstone's c.1804 variant, and also of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 variant (see Figure 5). For futher references to the tune, see also: Lady Ann Stewart's Strathspey at The Traditional Tune Archive

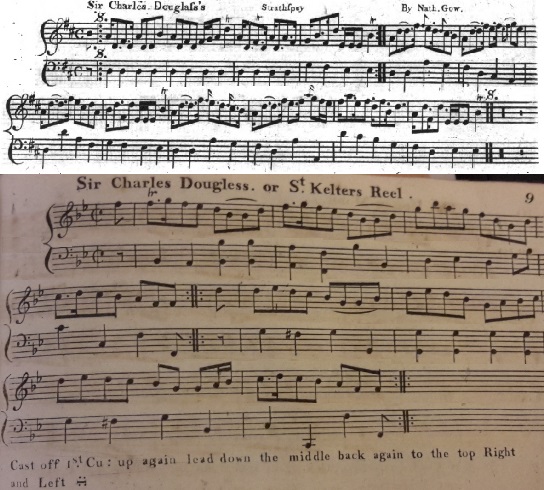

Sir Charles Douglass's Strathspey Figure 6. Sir Charles Douglass's Strathspey, from Niel Gow's 1800 A Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. (top), and Sir Charles Dougless, or St Kelters Reel from Charles Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favourite Country Dances (bottom).

Figure 6. Sir Charles Douglass's Strathspey, from Niel Gow's 1800 A Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. (top), and Sir Charles Dougless, or St Kelters Reel from Charles Wheatstone's 1806 Sixteen Favourite Country Dances (bottom).

at two, the ball recommenced with Sir Charles Douglas(First Ball) the ball was opened with Sir Charles Douglas, by Mr Sloane and Lady Maria Harris(Second Ball) soon after eleven, about one hundred having arrived, the ball was opened, with Sir Charles Douglas, and Jenny's Bawbie, as a medley, by Sir John Shelley, and Lady Madelina Sinclair(Third Ball) This tune is the only example that is known to have been danced at all three of our 1803 balls, it was clearly a favourite. It's also an anomaly, it's a rare example of a tune that was almost unpublished in London despite being widely danced. It was composed, once again, by Nathaniel Gow and was first published in Edinburgh in Niel Gow's 1800 A Fourth Collection of Strathspey Reels &c. (see Figure 6). The dedicatee was almost certainly Sir Charles Douglas, 6th Marquess of Queensberry (1777-1837); that stated, I note that several modern commentators identify the dedicatee as the long dead (but better known to posterity) Sir Charles Douglas, 1st Baronet of Carr (1727-1789). It's not possible to prove the identity of the dedicatee but tunes were generally named for a living patron (someone who might at least be expected to purchase a copy of the collection!); our Sir Charles went on to marry Lady Caroline Scott, a daughter of the Duke of Buccleuch, later in 1803.

The earliest printed reference that I can find to the tune is from an advertisement issued by the Gows in Edinburgh for their 4th Collection of Strathspey Reels (Caledonian Mercury, 2nd August 1800); the advert concluded by mentioning that Yet despite the popularity of the tune it seems not to have been published in London. We theorised that there may have been confusion amongst the London publishers over the Lady Anne Stuart tune above, we can be certain that there was confusion over the Sir Charles Douglas tune. Charles Wheatstone published the bizarrely named Sir Charles Dougless, or St Kelters Reel in his 1806 Sixteen Favourite Country Dances (see Figure 6); the tune printed was actually the unrelated St Kilda's Reel, a tune that is well known from other collections of a similar date. Another 1803 Ball held by the Ladies Townhend (Morning Post, 1st April 1803) featured both the Sir Charles Douglas and the St Kilda's Reel tunes; one can almost imagine an attendee selling a tune from that ball to Wheatstone, commenting that they couldn't remember the title; perhaps Wheatstone hedged his bets and named it Sir Charles Dougless, or St Kelters Reel to cover both possibilities! This confusingly named tune is the best evidence I can find of an attempt to publish the tune in London. There was another tune variously named as either Lady Mary Douglas or Miss Mary Douglass (or similar naming variants) that was widely published in London from around 1803, it's possible that the London publishers thought that the two tunes were the same. This alternate tune remained sufficiently popular for Thomas Wilson to publish a copy in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. But as popular as that tune may have been, it's unlikely to have been danced at our society balls of 1803; the elite tune must surely have been the tune promoted by the Gow band and derived from the Gow publication, it was briefly popular with the aristocracy and gentry even if the London publisher's had failed to publish it. It's curious that this same pattern exists for both the Lady Ann Stewart tune above and also the Sir Charles Douglass tune; in both cases a similarly named tune was more popular with the London music sellers at the same date, but in both scenarios the Gow tune is almost certainly what was being danced at the balls of the aristocracy. I'm not aware of any historical publications of this tune with suggested dancing figures attached; if you'd like to dance to the tune then you might like to arrange your own dancing figures, or perhaps use the figures that Wheatstone published for his tune (see Figure 6). For futher references to the tune, see also: Sir Charles Douglas's Strathspey at The Traditional Tune Archive

Sir David Hunter Blair's ReelThe second dance, Lady Ann Stuart, was succeeded by Sir David Hunter Blair(Second Ball) The tune named Sir David Hunter Blair must have been one of the most popular dancing tunes of the early 19th century; whether measured by social references or by publication frequency, both metrics suggest that it was generally known. It was widely referenced between about 1801 and 1804 and remained in regular use for over a decade thereafter, it was already an established favourite by the date of our ball in 1803.  Figure 7. Sir David Hunter Blair from William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys (top), from Nathaniel Gow's 1800 Captain Fletcher's Favorite (middle), and from William Campbell's c.1801 16th Book (bottom).

Figure 7. Sir David Hunter Blair from William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys (top), from Nathaniel Gow's 1800 Captain Fletcher's Favorite (middle), and from William Campbell's c.1801 16th Book (bottom).

The origins of the tune are a bit of a mystery. The initial publication of the tune (as far as I can discern) was in Edinburgh in Nathaniel Gow's 1800 Captain Fletcher's Favorite (see Figure 7, middle), Gow explicitly noted that the tune was of

The dedicatee, Sir David Hunter Blair (1778-1857) is readily identified, he became the 3rd Baronet of Dunskey on the death of his father in 1800; he was a young man of around 22 years when Gow first issued the tune. It's possible that he composed the tune himself but this seems unlikely, if he did then it's odd that he didn't go on to compose other popular tunes over the subsequent decades. It's improbably that Nathaniel Gow would have denied a Hunter Blair claim to the tune if it had been known, I therefore suspect that D.H.B. was not the original composer of the tune. Sir David Hunter Blair purchased the Blairquhan Castle estate in 1798 and went on to build the magnificent Regency castle there around 1820, it's possible that the Blairquhan purchase was the trigger for the dedication of the tune to him. If the tune genuinely was of The tune was sometimes published under the name Sir David Hunter Blair, sometimes as Sir David Hunter Blair's Reel, occasionally as Sir David Hunt of Blair or Sir David Hunter Blair's Fancy. Early publications include Bland & Weller's 24 Country Dances for 1802 (along with the equivalent 1802 collections issued by both the Preston and Thompson music shops), Goulding's. c.1802 1st Number, Dale's c.1802 1st Number and Davie's c.1802 4th Number. It can be found in Robert Mackintosh's Fourth Book of New Strathspey Reels published in London c.1803. It can also be found in both the Astor collection of 24 Country Dances for 1803 and in the Fentum collection of 24 for 1803; in Andrews's c.1804 5th Number and Walker's c.1804 6th Number, in Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and also in Button & Purday's c.1806 1st Number. It can be found referenced in Thomas Wilson's 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore, in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room, and also in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. It was also published in Abraham Mackintosh of Newcastle's c.1805 A Collection of Strathspeys, Reels, Jigs &c. and in Archibald Duff of Aberdeen's 1812 Part First of A Choice Selection of Minuets, Favorite Airs, Hornpipes, Waltzs &c.. It was widely available.

The tune was also widely danced. An 1800 advert (Caledonian Mercury, 2nd August 1800) issued by Nathaniel Gow indicated that this tune was among The first publication of the tune could have been in London, but the general popularity of the tune seems not to have been established until the Gows published and promoted the tune in Edinburgh. It was championed by the Gow bands, firstly in Scotland around 1800, then in London from around 1801. It was clearly a favourite tune in London. We've animated a suggested arrangement of William Campbell's c.1801 edition (see Figure 7), and of Button & Purday's c.1806 edition. For futher references to the tune, see also: Sir David Hunter Blair's Reel at The Traditional Tune Archive

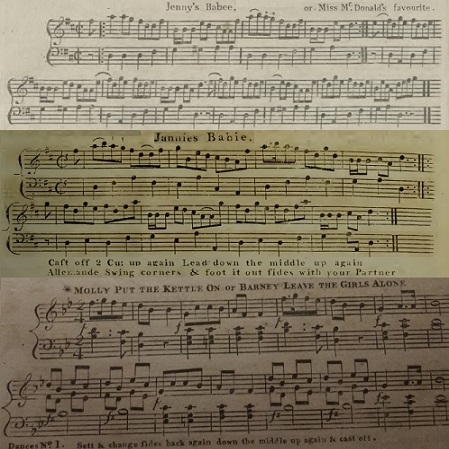

Jenny's Babee / Molly Put the Kettle Onthe ball was opened, with Sir Charles Douglas, and Jenny's Bawbie, as a medley, by Sir John Shelley, and Lady Madelina Sinclair(Third Ball) This tune was used in a medley arrangement along with the Sir Charles Stewart tune, medley arrangements were not uncommon at this date. The tune of Jenny's Babee was well known, it was widely published from the mid 1790s both in Scotland and in England and it remains well known today, albeit as a nursery rhyme. It was danced as the first dance of the evening at our third ball, led off by Lady Madeline Sinclair (1772-1847) the daughter of the hostess, the Duchess of Gordon; Madeline had been married to Sir Robert Sinclair 7th Baronet of Stevenson and Murkley, he had died in 1795 leaving her a widow (she would subsequently remarry in 1805). Her partner for our dance was Sir John Shelley (1771-1852).  Figure 8. Jenny's Babee from Archibald Duff's c.1794 A Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (top), Jannies Babie from William Campbell's c.1794 9th Book (middle), and Molly Put the Kettle On, or Barney Leave the Girls Alone from Button & Purday's c.1806 1st Number (bottom). Bottom Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 8. Jenny's Babee from Archibald Duff's c.1794 A Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (top), Jannies Babie from William Campbell's c.1794 9th Book (middle), and Molly Put the Kettle On, or Barney Leave the Girls Alone from Button & Purday's c.1806 1st Number (bottom). Bottom Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The earliest publications of the tune that I can identify were all issued c.1794, twice in Scotland and once (perhaps twice) in London; the Scottish publications were in Archibald Duff's c.1794 A Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (see Figure 8, top) and in the c.1794 4th volume of John McFadyen's A Selection of Scotch, English, Irish and Foreign Airs (the first three volumes of which were issued by James Aird). Both works published the tune under the name Jenny's Babee, although Duff added the suffix

The tune has been issued under various names including Jenny's Babee, Jannies Bawbee, Jennie's Babie and Jenney's Baubee. It is better known today under the names Molly Put the Kettle On and Polly Put the Kettle On, names which emerged (based on newspaper references) from around the year 1800; it was also popular as the tune for a comic song named Barney Leave the Girls Alone that appeared on the London stage from around 1802. References to the tune date back at least as far back as 1776 (when it was named in James Dickson and Charles Elliot's Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, etc. Volume 2), it was presumably a popular tune even before it appeared in print. A It went on to be published in Edinburgh in Robert Mackintosh's c.1795 3rd Book of Sixty Eight New Reels and Strathspeys; 1799 saw the tune published in Edinburgh in Niel Gow's Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances, in Dublin in Hime's Collection of Favorite Country Dances for the present Year 1799 and in London in Kaunte's c.1799 Collection of the most favorite Dances, Reels, Waltzes, &c. It was at some point around this same date that Nathaniel Gow included the tune in his March of Col. Graham of Balgowan's Perthshire Volunteers published in Edinburgh c.1800, also as a song; the tune had been published in a rondo arrangement since at least as early as 1796 (Caledonian Mercury, 18th April 1796). It was published many more times in London over the next few years, examples include: the Milhouse collection of 24 Country Dances for 1801, Goulding's c.1802 2nd Number, Davie's c.1802 4th Number, Dale's c.1802 2nd Number, Walker's c.1804 7th Number, Andrew's c.1804 4th Number, Cahusac's 24 Country Dances for 1804, William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and in Button & Purday's c.1806 1st Number (see Figure 8. bottom). It remained sufficiently popular for Thomas Wilson to reference the tune in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and to publish the tune in his 1816 Companion to the Ball Room, it was also listed in Edward Payne's 1814 A New Companion to the Ball Room. It was danced at several society balls in London from around 1803; examples include Her Majesty's Ball (Lancaster Gazette, 28th May 1803), Mrs Thompson's Ball (Morning Post, 25th June 1803), Mrs Duff's Ball (London Chronicle, 24th July 1804) and the Ball at the Castle in Brighton (Kentish Weekly Post, 16th August 1805). The tune was certainly well known, it was probably at the peak of its popularity in 1803. We've animated a suggested arrangement of Button & Purday's c.1806 edition (see Figure 8, bottom), of William Campbell's 1794 version (see Figure 8, middle), and of Maurice Hime's 1799 version. For futher references to the tune, see also: Jenny's Bawbee at The Traditional Tune Archive

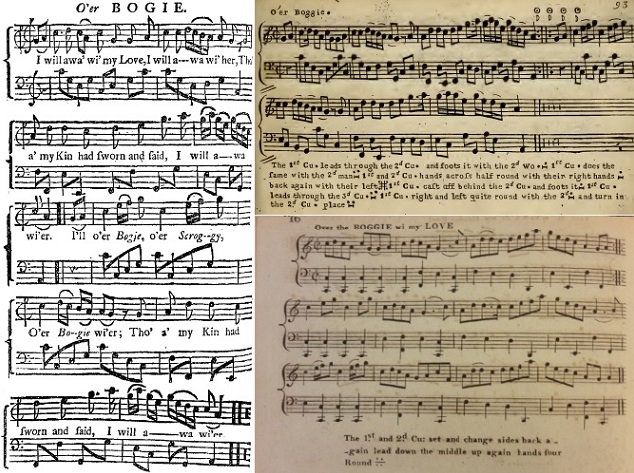

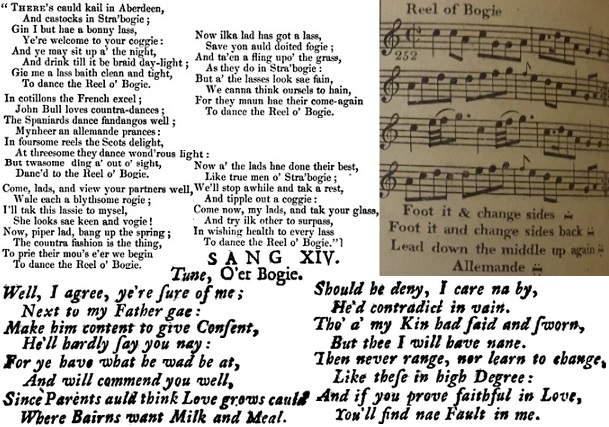

O'er Bogie wi' my Love / O'er Bogie / Reel of Bogiebefore four o'clock the ball was recommenced by the Marquis of Huntley and Lady Sarah Fane; the latter called for the old favourite dance, O'er Bogie wi' my love. It was kept up with proper spirit.(Third Ball)  Figure 9. O'er Bogie from the 1731 5th Volume of John Watt's The Musical Miscellany (left), O'er Boggie from John Walsh's 1733 first volume of his Caledonian Country Dances (top, image is of the 1736 3rd edition), and Over the Boggie wi my Love from William Campbell's c.1804 19th Book (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9. O'er Bogie from the 1731 5th Volume of John Watt's The Musical Miscellany (left), O'er Boggie from John Walsh's 1733 first volume of his Caledonian Country Dances (top, image is of the 1736 3rd edition), and Over the Boggie wi my Love from William Campbell's c.1804 19th Book (bottom). Bottom image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.96. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

O'er Bogie is an old tune, it was widely published in the 1720s and 1730s but it is thought to be older still. One of the earliest publications of the tune in London can be found in the 1731 5th Volume of John Watt's The Musical Miscellany under the name

Publications of the tune arranged as a Country Dance can be found in most decades thereafter; the narrator of our ball described it as The tune was called for by Lady Sarah Fane (1785-1867), she would go on to become the celebrated Countess of Jersey after marrying the Earl of Jersey in 1804. Fane was herself the progeny of an eloped marriage, her parents (Sarah Child (1764-1793) and John Fane (1759-1841) 10th Earl of Westmorland) were wedded without permission at Gretna Green in 1782. Her immensely wealthy maternal grandfather, slighted in his choice of son-in-law, wrote a complicated Will that ensured that his riches would not be inherited by her older brother (the inheritor of the Westmorland title); this resulted in Fane becoming one of the richest women in Britain while still a youth. It's possible, perhaps even likely, that she was aware of the song and had adopted the tune as a personal favourite in memory of her mother. In later years she would become associated with the introduction of both the Waltz and Quadrille dances to London, she would also be active as a patroness of the immensely significant Almack's Assembly Rooms; she would famously waltz with the Tsar of Russia during his visit to London of 1814. Her partner at our Ball was George Gordon (1770-1836), the eldest son of our hostess the Duchess of Gordon... perhaps the Duchess hoped that her son and the 18 year old heiress might become attached to each other. George was the Marquess of Huntly, the River Bogie in Aberdeenshire happens to flow through the town of Huntly and might have provided a suitable excuse for the Duchess to engineer this particular partnership. The couple had already danced together for the first dance of the evening, partnering for this additional dance might have elicited a degree of gossip amongst the attendees! The Gordon connection to the tune runs still deeper. Alexander Gordon (1743-1827), 4th Duke of Gordon (the husband of our hostess) authored alternative lyrics (in a comic style) to the old song of Cauld Kail in Aberdeen c.1787, his refrain to which referred to the Reel of Bogie (see Figure 10); for example, his second verse is packed with dance references and reads: These lyrics were collected by Robert Burns and published in James Johnson's 1788 second volume of The Scots Musical Museum, they clearly indicate the significance of the tune to the Gordon family. An older version of the lyrics also referred to the Reel of Bogie, this variant dated back to at least 1776 at which date they appeared in James Dickson and Charles Elliot's Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, etc. Volume 2. Other variants of Cauld Kail are somewhat older still; references, for example, to both the Kail and Bogie tunes coexist within Allan Ramsay's 1725 play The Gentle Shepherd: A Scots Pastoral-Comedy. Ramsey's song to the tune of O'er Bogie is particularly interesting as he'd comically altered the lyrics to emphasise the desirability of parental consent to marriage (see the bottom of Figure 10 and compare them to the left of Figure 9).In Cotillons the French excel;

Figure 10. The Duke of Gordon's c.1787 lyrics to Cauld Kail in Aberdeen (top, left), the Reel of Bogie from the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1794 (top, right), and Allan Ramsay's song from his 1725 play The Gentle Shepherd: A Scots Pastoral-Comedy (bottom).

Figure 10. The Duke of Gordon's c.1787 lyrics to Cauld Kail in Aberdeen (top, left), the Reel of Bogie from the Preston collection of 24 Country Dances for 1794 (top, right), and Allan Ramsay's song from his 1725 play The Gentle Shepherd: A Scots Pastoral-Comedy (bottom).

Reel of Bogiein their 24 Country Dances for 1794 (see Figure 10). One of the more interesting publications can be found in Edinburgh in Niel Gow's 1802 Part Second of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Tunes, Strathspeys, Jigs and Dances under the name O'er Bogie wi' my Love, this was the first dance publication (as far as I can determine) to use this longer version of the title. It's possible that the Gow publication, together with promotion of the tune by the Gow bands, brought the tune to the attention of the London fashionables; it's perhaps significant that the tune became known by the longer name thereafter. The tune featured at our Ball of 1803, it then went on to appear in collections issued by numerous London music sellers; examples include William Campbell in his c.1804 19th Book (see Figure 9, bottom), Andrews in his c.1805 9th Number, Dale's c.1806 8th Number, Walker's c.1806 10th Number, Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 1st Book, William Napier's c.1806 Selection of Dances & Strathspeys and James Platts in his 1810 20th Number. It was printed in Archibald Duff of Aberdeen's 1812 Part First of A Choice Selection of Minuets, Favourite Airs, Hornpipes, Waltzs &c., was mentioned in Edward Payne's 1814 New Companion to the Ball Room and was included in Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room. It had remained somewhat popular over around a century of dance publishing history, though never more so than in the years immediately following 1803. The earliest reference I have to the tune being enjoyed for social dancing involves our Ball of 1803, it would also be danced a week or so later at The Duchess of Devonshire's Ball where it was once again selected by Lady Sarah Fane (Morning Post, 9th July 1803). It went on to be danced at: The Duchess of Bolton's Ball (Morning Post, 20th March 1805), Lady Carrington's Second Ball (Morning Post, 8th April 1805), Lady Ferrers Townshend's Ball (Morning Post, 4th May 1805), Mrs DuPre's Grand Ball (Morning Post, 7th June 1805), Mrs Browne's Ball (Morning Post, 22nd June 1805), The Duchess of Gordon's Ball (Morning post, 8th March 1806) and at Mr Brewer's Ball (Kentish Chronicle, 5th January 1808). We've animated suggested arrangements of the Preston version of 1794 (see Figure 10), William Campbell's c.1804 version (see Figure 9), Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1806 version and of James Platts's 1810 edition. For futher references to the tune, see also: O'er Bogie at The Traditional Tune Archive

French Figure DanceA French figure dance was afterwards called for by the Duchess of Gordon; but the dancers were unable to attack it, being quite overcome by the heat and fatigue.(Third Ball) The third ball should have closed with a French Figure Dance, unfortunately the dancers were sufficiently exhausted by 7am that they were unwilling to take it on, despite the urging of their hostess. A figure dance is a choreographed dance, the performers needed to have rehearsed the figures in advance; perhaps a small group of the Duchess's friends had memorised a suitable routine but some of their number proved unable to perform. Figure dances are distinct from the Country Dances that would make up most of the programme for the ball, with country dancing the figures might be selected or adopted in-situ with little preparation required.

Figure 11. The York Minuet, 1791. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

Figure 11. The York Minuet, 1791. Courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

French Figure Danceis one we've considered in a previous paper, you might like to read more there; it might refer to a couple dance such as a Minuet (see Figure 11) or even a French Country Dance (possibly a Cotillion or a variant thereof). The Marchioness of Abercorn hosted a ball in 1805 in which the first dance was a French figure-dance for two persons, performed in the same style as the Scots Strathspeys. It was much admired, and the dancers were applauded exceedingly, particularly by the Duchess of Gordon, who was present(The Morning Post, 25th February 1805), it's probable that a similar dance would have been attempted at our Ball. The Waltz was being danced at society balls from around the turn of the nineteenth century, it's plausible that it could have been described somewhat generically as a French Figure Danceand might even have been what the Duchess had planned. The precise nature of what the Duchess had in mind is not clear and it wasn't actually danced; whatever she intended would have been a little unusual, something other than the common style of Country Dances and Reels from the preceding few years.

Portuguese Figure Dance... and concluded at three with a Portuguese figure dance, which produced much mirth, from the whimsicality of the different postures, it was necessary for the dancers to assume, in order to keep the figure correct.(First Ball) The concept of a French Figure Dance may be a little vague, unfortunately the concept of a Portuguese Figure Dance is even more so; this is the only occurrence of the phrase that I'm aware of across many decades of British dance history, the dance implied may have been unique to this event.

As with any other figure dance we can assume that this dance was choreographed, beyond that little is obvious. Around forty guests were present for the ball, it was a relatively select company of friends in which the stricter rules of propriety might perhaps be suspended, it may have been a little sillier (or more The concept of a Spanish Figure Dance was also current at this date and referred to such dances as the Fandango, Bolero, or similar. Dances involving the use of castanets would become fashionable around the year 1804, it's possible that a Portuguese Figure Dance might have involved the use of Iberian instruments, this gathering may have been ahead of the rest of the nation in doing so. Or perhaps it was a precursor to the shawl dance which would amuse the nation in 1805. All we can do is guess about the nature of the dance. The description, brief as it is, seems as much a game as a dance - maybe the dancers were required to adopt a characteristic of some kind as the dance progressed. It clearly induced much merriment and laughter amongst the company, it was something other than the typical dances of the period.

Reels, Strathspeys, Medleys and Country DancesAt two the ball re-commenced, and concluded with Reels and Strathspeys, at half after three, when the company departed.(Second Ball) Medleys, reels and country dances, continued, without intermission, for upwards of three hours(Third Ball)

The phrases

For example, the words  Figure 12. A detail from La belle assemblée, or, Sketches of characteristic dancing, 1817.

Figure 12. A detail from La belle assemblée, or, Sketches of characteristic dancing, 1817. Image courtesy of the Lewis Walpole Collection.

Similarly imprecise descriptions of Scottish themed dancing can be found from other historical balls of a similar date. For example, The Countess of Leicester's Ball (The Times, 30th April 1800) featured

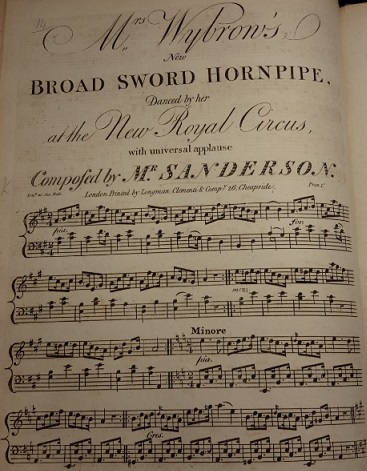

Figure 13. Mrs Wybrow's New Broad Sword Hornpipe, by James Sanderson, 1799. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.229.(14.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 13. Mrs Wybrow's New Broad Sword Hornpipe, by James Sanderson, 1799. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.229.(14.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Mrs Wybrow's HornpipeBefore the company entered into the spirit of the ball, they were entertained by the Hon. Mr Stanhope, a boy of nine years old (son of Lord Harrington), who danced Mrs Wybrow's hornpipe in very fine style, to the music of the Savoyards.(Third Ball) The last dance to be mentioned across our three balls was actually performed before the third ball began; it was a performance by the nine year old Augustus Stanhope (1794-1831) of a choreographed Hornpipe dance. He was the youngest son of Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl of Harrington; he was presumably invited to demonstrate a routine that his dancing master had taught him, his audience would no doubt have been complimentary in their praise. Mrs Wybrow was a popular stage performer, an actress and dancer. The composer James Sanderson registered a publication for copyright purposes at Stationer's Hall on the 11th September 1799 titled Mrs Wybrow's new broad sword Hornpipe. Danced by her at the new Royal Circus, with universal applause (see Figure 13). It was evidently this dance that the young Mr Stanhope performed, a copy of the score is available through Google Books. I don't have much insight into the nature of the solo dance performance, but dancing masters continued to teach the Broad Sword Hornpipe for some years beyond this date; Thomas Wilson, for example, offered to teach it at a cost of 5 pounds and 5 shillings in an advertisement of 1808. There were many signature hornpipes that were danced on stage at around this date; for example, a Mr Wilson (probably Thomas Wilson himself) was noted for his Rifle Hornpipe dance in 1805 (Public Ledger, 5th October 1805); by 1808 Wilson also taught the Ground Hornpipe, Tambarine Hornpipe and Corsair Hornpipe dances. A few early 19th century solo hornpipe choreographies do survive in the wonderful c.1826 T.B. Manuscript (the personal collection of an unknown but probably Scottish dancing master), including Milanie's Hornpipe and Foullon's Hornpipe; we've speculated on the authorship of that collection elsewhere.

There are hints that the broadsword hornpipe may have been a comic dance, perhaps performed in faux-armour; it was named in reference to (and was probably also derived from) the

Mrs Wybrow wasn't the most celebrated performer of the Broad Sword Hornpipe (the Misses Adams and Miss Gayton were more prominent in the London advertisements), but it was her signature dance. She was still performing it in 1804 when it was reported of Sanderson's benefit night at the Royal Circus that The stage hornpipe tunes were often quite popular with the public, they would sometimes be adapted for Country Dancing. For example, the Goulding collection of 24 Country Dances for 1800 includes a tune named The Broad Sword Hornpipe, as does the equivalent Preston collection for 1801. Thomas Wilson even published Mrs Wybrow's Hornpipe under the name Circus Hornpipe in his 1816 Companion to the Ballroom with three different suggested country dancing arrangements (an observation to which I'm indebted to the Traditional Tune Archive).

This wasn't the only ball at which a favoured child was invited to demonstrate a choreographed stage dance, it may indeed have been a common occurrence but we rarely find this level of detail. A second description of the same ball was printed in the British Press newspaper for the 29th of June 1803, they described what must have been the same performance in a different way: For futher references to the tune, see also: Mrs. Wybrow's New Broad Sword Hornpipe at The Traditional Tune Archive

ConclusionWe've studied three private balls in this paper. They were held in neighbouring properties within 3 months of each other in 1803. The guests were notable socialites, the dancers were (mostly) unmarried yet eligible members of the nation's more prominent families. The dances were a mixture of Country Dances (danced to Scottish tunes) and choreographed figure dances; we're informed of at least one stage dance being performed by a favoured child. One notable detail was that some of the dancing was conducted on carpet; modern re-enactors who are lucky enough to dance at prestigious venues might be asked to dance on carpet, the convention wasn't entirely unheard of 200 years ago. It was however sufficiently unusual to have been comment-worthy on an occasion when it happened. A second uncommon detail involved the ladies at one of the balls starting the dancing before the gentlemen had even arrived.Some of the tunes at our balls were sufficiently fashionable to have been used at more than one of the events. Tunes of Scottish origin had been popular in London for the previous few decades, this was increasingly the case in the early 19th Century. The balls of the London nobility often featured them, together with the dancing of Reels and Strathspeys. The Duchess of Gordon is recognised as having promoted Scottish themed culture in London at around our date, it's therefore interesting to read a more detailed account of the type of event that she would personally host. In addition to the Scottish themed dancing she had requested a French Figure Dance, she also permitted a stage Hornpipe to be danced by the young son of one of her guests. She may have been known for promoting Scottish culture but she was sufficiently cosmopolitan to support whatever was fashionable.

It particularly amuses me to know that Jenny's Bawbie, a tune better known as a modern nursery-rhyme, was danced at the Duchesses' ball. Some modern authorities may dismiss We'll leave this investigation there, if you have any additional information to share do Contact Us, we'd love to know more.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2024

All Rights Reserved