|

Paper 35

Programme for a Royal Ball, 1813

Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor

[Published - 17th April 2019, Last Changed - 6th June 2023]

The Prince Regent hosted a Grand Ball to celebrate his mother's birthday in early 1813, it elicited some excitement with the public and the list of dances that were enjoyed still survives. Similar balls were held in celebration of the Queen's Birthday each year, they were held on the magnificent scale one might expect of the Royal family. This particular Ball was hosted at Carlton House (the Prince's residence in London) on the evening of Friday 5th February 1813. In this paper we'll investigate the dancing and discover what we can of the Ball itself.

The tunes we'll be investigating further in this paper are:

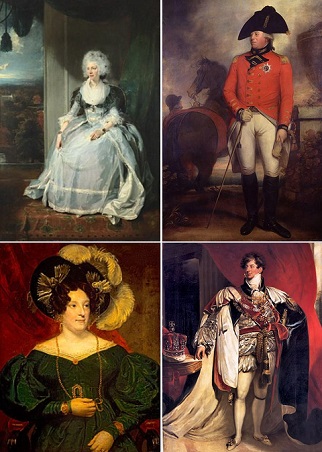

The Royal Family in early 1813

In order to understand the context of the Ball we should take a few moments to understand why the nation's interest was especially invested in this event. That in turn requires a little insight into the structure of the Royal Family. The reigning monarch was King George III (1738-1820), he was the infamously mad King George (see Figure 2). He was married to Queen Charlotte (1744-1818). Their eldest son was Prince George, the Prince of Wales (1762-1830) who acceded to the Regency in 1811 when his father was no longer considered fit to rule; he would later become King George IV. Prince George was married to Princess Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), they had just one child together, Princess Charlotte of Wales (1796-1817) (see figure 1). Charlotte was, at this time, King George III's only legitimate grand-child and second in line to the throne; numerous illegitimate grand children were rumoured to exist, but it was on the 17 year-old Charlotte's young shoulders that the future of the monarchy was expected to rest.

The Regent and his wife suffered a troubled marriage, they lived apart and barely spoke. Princess Caroline's access to Princess Charlotte was significantly restricted, the young princess led a sheltered life. Caroline sent a formal letter to the Prince Regent dated 14th January 1813 begging the Regent to allow her access to her daughter, she had very personal reasons for wanting that, but she made her case for the good of the state: the Princess must be trained to become the Queen the nation expected her to become. The letter was subsequently leaked to the press (for example in the Northampton Mercury for 13th February 1813); Caroline argued that her daughter must be allowed to enter society as it may so happen, by a chance which I trust is very remote, that she should be called upon to exercise the powers of the Crown, with an experience of the world more confined than that of the most private individual .

The British public thought that Charlotte would be formally presented to the Queen and Court, and that this Ball would be conducted in honour of their future Queen. Things did not work out that way; the Princess was not presented at Court that day, nor did she go on to become the nation's monarch... she died in 1817 and the nation mourned. The King himself died in 1820, and so the Prince Regent became King George IV; he in turn died in 1830, and his younger brother became King William IV (1765-1837). It was William and George's niece Princess Victoria (1819-1901) (daughter of their Brother Edward) who would go on to become the Queen that the nation had hoped some day to have in Princess Charlotte.

But returning back to January 1813, the existence of the infamous letter was not yet publicly known. It was reported that it was transmitted on the 14th ult. to Lord Liverpool and Lord Eldon, sealed, by Lady Charlotte Campbell, as Lady in waiting for the month, expressing her Royal Highness's pleasure that it should be presented to the Prince Regent; and there was an open copy for their perusal. On the 15th the Earl of Liverpool presented his compliments to Lady Charlotte Campbell, and returned the letter unopened, as we have stated. On the 16th, it was returned by Lady Charlotte, intimating, that as it contained matter of importance to the State, she relied on their laying it before his Royal Highness. It was again returned unopened, with the Earl of Liverpool's compliments to Lady Charlotte, saying, that the Prince saw no reason to depart from his determination . The epistolic saga evidently continued for several further days. The nation weren't to know of these tabloid details until a few days after the Ball, but they were genuinely excited; the crowds were especially heavy. The Windsor and Eton Express for 7th February 1813 wrote of the Ball that it had excited so much interest, that crowds of spectators continued opposite Carlton-House nearly the whole night. .

The Norfolk Chronicle (13th February 1813) wrote of the ball that A question of etiquette had been previously agitated, whether the Princesses, the King's daughters, or the Princess Charlotte of Wales, should have the precedence in opening the ball; it was determined in favour of the Lady Aunts . It went on to describe what the young Princess wore that evening: The Princess Charlotte of Wales was attired as follows:- A splendid dress of white lace, richly embroidered in lama silver; body of silver tissue; sleeves of patent net, elegantly embroidered in diamond points, with beautiful armlets to correspond. Head-dress, plume of white ostrich feathers, supported by a most beautiful diadem; neckless of rubies and diamonds. . It continued: The introduction of this Princess to public life, with other circumstances, has raised a greater interest than ever in the minds of people on the unhappy differences subsisting between her Royal Parents. . Princess Charlotte may have remained oblivious to all this excitement; even the vexed question of who she should wed had yet to become a concern - that problem would be a drama for later in the year.

The Prince Regent's Ball and Supper (Friday 5th February 1813)

Figure 3. Rooms of Carlton House. Entrance Hall (above), Conservatory (middle), Gold Room (below), Grand Staircase (right). Images from Pyne's 1819 The History of the Royal Residences.

What follows is the description of the Ball as printed in the Windsor and Eton Express for 7th February 1813, the dance references have been emphasised. Figure 3 contains images of the rooms at Carlton House that are mentioned in the text.

This entertainment, in honour of the Queen's Birthday, took place on Friday evening. It had excited so much interest, that crowds of spectators continued opposite Carlton-House nearly the whole night. Every arrangement was made for facilitating the access of the distinguished visitors to the superb mansion, by stationing the Guards and Police Officers in every direction near it. The Court-yard was illuminated. The Band stationed therein, continued playing till all the company arrived. Those who had the honour of supping at his Royal Highness's table, passed straight through the hall at their entrance; the other visitors turned to the right. The number at the Prince's table did not exceed sixty, including the Royal Dukes. The company promenaded through the suite of State-rooms and partook of tea, coffee, and other refreshments.

About a quarter before eleven, the Royal Family, consisting of the Queen, Prince Regent, Princess Charlotte, Princesses Elizabeth and Mary, Duke and Duchess of York, the Dukes of Clarence, Kent, Cumberland, and Cambridge, and the Princess Sophia of Gloucester, entered the rooms. Arrangements were then made for dancing; a Band of the first-rate musicians, under the direction of Mr Oliver, appeared in a recess. The Ball was opened by the Duke of Cumberland and Princess Mary, to the tune of Gang no more to yon Town. The second dance was, Miss Johnston, which was led off by the Duke of Clarence and the Princess Charlotte. The third dance was The Prince Regent, led off by the Duc de Berri and Princess Charlotte. The fourth dance was Draycott-House, which was led off by the Duke of Clarence and Princess Mary. At the conclusion of this dance the Band struck up the Fairy Dance. It being now one o'clock, the dancing was suspended, and preparations were made for the company's adjourning to sup in the Conservatory and splendid range of rooms adjoining. The Royal Family, and a select party, descended from the Gold Room by a private staircase, to the Conservatory. The rest of the visitors went down the grand staircase. The Prince's table was laid for 65. The Queen and Prince Regent sat at the head; the Princess of Conde sat next to her Majesty; the Princess Charlotte sat at the right of the Duke of York; the Lord Chancellor sat at the bottom of the table; the Dukes of Bedford, Norfolk, Leinster, Rutland, and Manchester, most of the Cabinet Ministers, the Groom of the Stole, the Officers of State belonging to the Queen and the Prince Regent, some Foreigners of distinction, and a few of the principal Nobility, completed the original number. After super, the Prince proposed the health of his Royal Father, on which a Band, appropriately stationed, struck up God save the King ; which was followed by a Russian march, in compliment to the Russian Ambassador.

After supper, dancing was resumed with the greatest spirit; the first dance was led off by the Duke of Clarence and the Princess Charlotte, to the tune of Because he is a bonnie Lad, which was followed by Fight about the Fire-side, after which The Lads of Ayr, and concluded with The Birks of Aberdeen.

The Norfolk Chronicle printed almost the same text, but added that Her majesty and Princess Charlotte of Wales, and the other Princesses, did not withdraw till near five o'clock, and the rest of the company not till six . Similar text was printed in The Times (8th February 1813), but with the added detail that Colonel Braddyll was selected for the honour of presenting tea to the Princess Charlotte .

The Morning Post for 8th February 1813 described the ball as the grandest fete which has ever been witnessed since the days of Henry VIII . It described the richest draperies of blue velvet, enriched with massive fringes of real gold, half a yard deep. Five chandeliers of matchless beauty and perfection illuminated the apartment ... The floor was chalked with appropriate devices in the best possible style. In the recess of the principal windows, a temporary orchestra was erected to contain fourteen choice musicians, selected and ably led by the celebrated Gow. ... The female head-dress was the same through-out, namely a-la-greque, with a plume of ostrich feathers, introduced solely in compliment to the Regent's crest. The greater proportion of the Gentlemen were dressed a la militaire . It reported that The Princess Charlotte went down only two dances, when her Highness complained of fatigue. The Princess Mary went through no less than nine dances, with her accustomed spirit. . It mentioned the special interest the Queen took in the Russian ambassador's wife (this was the celebrated Countess Lieven), and listed details of the costumes that many of the ladies wore.

A more fulsome account of the Ball, and particularly of the more political speeches made by the Prince at supper, can be found in Volume 13 of The Literary Panorama, a copy of which is available on the web courtesy of Google Books.

The dancing evidently consisted of Country Dances; there's a hint that a Polonaise March may have also been introduced, but the reference is a little too vague to be certain. We have no insight into the figures that would have been danced to those tunes, the convention was for the couple that led-off the dance to select the tune and figures to be danced, the tunes themselves are known and mostly of Scottish origin (so too was the leader of one of the orchestras, though which of the Gow brothers conducted the music isn't clear). A single Country Dance could easily last for 20 minutes, perhaps much longer, so a relatively small number of tunes would be sufficient for a Ball; the leading couple would usually dance from the top of the set down to the bottom, back to the top, and down a second time - it's no wonder that the Princess was fatigued after leading two such dances! The second and subsequent couples would have a slightly easier time, they were only expected to progress to the bottom and then back to one position above where they started; they'd get some rest while stood-out . Scottish themed dancing was popular with the Prince; he'd appointed the Scottish dancing master George Jenkins to teach Princess Charlotte from the tender age of 5 back in 1801, she probably knew most of the tunes.

Let's consider each of those named tunes in turn.

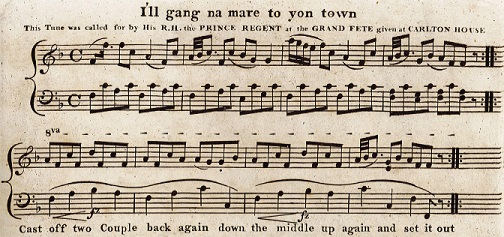

I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon Town

The Ball was opened by the Duke of Cumberland and Princess Mary, to the tune of Gang no more to yon Town.

This tune was a particular favourite of the Prince of Wales, the Morning Post even reported that The Prince Regent called the first dance; it was the celebrated Scots tune of I'll go no more to yon town. The Duke of Clarence and the Princess Mary led off, followed by the Duke of Cumberland and the Princess Charlotte of Wales (the accounts differ over who led off this dance). It was unusual for one person to call (i.e. select) a dance and for someone else to lead off, but the Prince wasn't dancing that evening; he did however select the very first tune of the evening. Indeed, this tune was often the first to be danced at any Ball. It was one of the most popular and best documented tunes for fashionable dancing of the early 19th Century; it was understood to be the Prince's favourite, and so it was widely danced in the elite circles that were likely to receive Royal patronage. The newspaper descriptions of Society balls referenced it regularly from around the turn of the century straight through to the 1820s, it was even played continuously for 2 and a half hours at one fashionable event. It was arguably the single most popular such tune of the period... and yet it's largely forgotten today. We've animated arrangements of Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 edition (see Figure 5), and of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1810 edition.

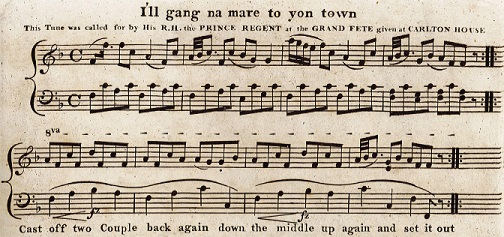

Figure 5. I'll gang na mare to yon town, from Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 15th Number. Image courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), EFDSS.

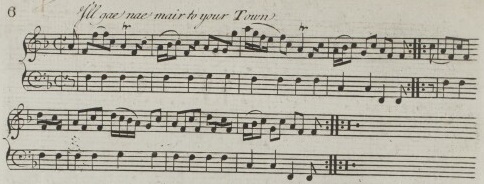

The first known edition to be printed was that of Robert Bremner in his c.1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (see Figure 6); it went on to be published in various Scottish collections in the later 18th Century. Examples include: John Bowie's c.1789 Collection of Strathspey Reels & Country Dances, Robert Petrie's 1796 A Second Collection of Strathspey Reels &c (under the name I'll go no more to yon town, or Mr Small's favorite Reel); and Niel Gow's 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances.

Early London publications of the tune (after that of Bremner, who printed his collection in both Edinburgh and London) can be found in a c.1789 collection of scarce and favorite Scots Tunes issued by the Thompson's under the name The Caledonian Muse; it was also published in Longman & Broderip's collection of 200 Country Dances at around the same date under the name We'll gang no more to yonder. I've identified versions issued by a further 15 London music publishers issued between about 1798 and 1813, it's likely that most of the vendors had copies to sell; not all of those editions have dancing figures attached, but of those that do every suggested choreography was different. One of the first to market after the Thompson's may have been the Dale edition in their c.1804 3rd Number, but the first with a suggested choreography may have been that of William Campbell in his 1806 21st Book. Thereafter versions were issued at irregular intervals by the various publishers, with a late burst of enthusiasm for the tune c.1813 with five late comers issuing it at around that same date. My archives are of course incomplete, I suspect that a good many more editions issued by London publishers are yet to emerge. Most vendors issued the tune under the same name, though a few variant spellings are encountered; one of the more interesting titles is that of Wheatstone & Voigt's c.1810 Book 5 where it's named I'll Go No More To Yon Town, or The Princes Favorite. Numerous different tunes were assigned the name The Prince's Favorite, but this tune has a legitimate claim to the appellation. Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 15th Number also had an unusual note attached, they recorded that This Tune was called for by His R.H. the Prince Regent at the Grand Fete given at Carlton House (see Figure 5) in reference to the Grand Ball held in 1811 that marked the formal commencement of the Regency, it was one of only two dances to be enjoyed that evening.

A further unusual name for the tune can be found in Thomas Wilson's 1816 A Companion to the Ball Room; Wilson named it The Lass in Yon Town and added a explicit footnote to record that This is frequently called I'll gang na mair to yon Town, but this is the proper name . It's unclear from where Wilson sourced his information, but he appears to have been mistaken; the popular name of the tune was also the oldest known name.

Figure 6. I'll gae nae mair to your Town, from Robert Bremner's 1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances. Image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

References to this tune being enjoyed in polite society are manifold, this is despite the newspaper reports infrequently naming the tunes that were danced; where tunes are named we might only learn the first of the evening. There are tunes that must surely have been popular (based on a frequency analysis of publication) that might not get mentioned at all, or perhaps only once over a decade of relevance. This tune is completely different, a couple dozen or more Balls can be shown to have featured it. One might imagine that the Prince would get bored of hearing the same music everywhere he went!

Our first such reference is from 1801, The Courier (18th April 1801) reported on Lady Saltoun's Ball: At three o'clock the dances recommenced with Sir David Hunter Blair, and Go no more to yon Town, a Medley ; this 1801 date may have been before the Prince became associated with the tune, but the association existed by 1804 when the Chester Chronicle (3rd August 1804) reported on the Duchess of St Alban's Ball: At half past three the Prince rose from supper, and joined the festive throng in the ball-room, when the ball was opened with his Royal Highness's favourite tune We'll gang na more to yon town . The Duchess of Bolton's Ball the following year (Morning Post, 20th March 1805) featured I'll go no more to yon Town, which was afterwards danced as a medley with O'er the Bogie wi my Love (only using the tune once in an evening presumably wasn't sufficient); a little later Lady Townsend's Ball would open with the tune (Morning Post, 4th May 1805), as would Viscountess Duncannon's Ball (Morning Post, 15th July 1805). An elegant public breakfast in 1806 involved 12 couples standing to dance to the tune (The Courier, 20th August 1806), and Captain Fitz-Clarence's Ball in 1809 involved 25 couples dancing to the tune (Morning Post, 29th December 1809).

A very unusual anecdote was shared regarding a fete-champetre in honour of the Duke of York's Birthday in 1809, the Morning Post (18th August 1809) reported: The Prince of Wales called the first dance for the Duchess of York, I'll go no more to your town. Her Royal Highness went down the dance with Lord Delvin, and in a style of great animation. The Duke of Clarence followed, with one of the Duchess's favourite attendants; and Sir Culling Smith with another. The dancing became general among the servants and peasantry, soon after ten o'clock. It was impossible for the Prince to contain his gravity long, the scene became so irresistibly comic, from the circumstance of the gentry dancing one figure, and the country people another, that the peals of laughter were long, loud and reiterated. . Royalty and peasantry dancing together, seemingly in good natured competition! A similar event was held the following year (Morning Post, 18th August 1810) in which once again the Prince called for the festivities to start with the same dance; this time the music was led by Mr Gow, just as with our 1813 Ball.

Several Balls of 1811 were recorded to have used the tune, the most unusual reference being that of Lady Tylney Long's Fete (Morning Post, 12th July 1811): The Prince Regent's favourite tune, I'll gang no more to yon town, was correctly and spiritedly played by Mr Gow's band. Miss Tylney Long led off the dance with Mr Crawfurd ... The dance was so highly approved of, that the musicians continued playing it for no less a time than two hours and a half; only one succeeded it, the Persian Dance . . Almost the entire event was taken up with just that one tune! Further references can be found throughout the 1810s and early 1820s, including for Balls at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, but the point has been made; it genuinely was the Prince's favourite tune, it's no surprise that he called for it to open his Ball in early 1813.

For futher references to the tune, see also: I'll Gang Nae Mair to Yon Town at The Traditional Tune Archive

Miss Johnston of Huttonhall's Reel

The second dance was, Miss Johnston, which was led off by the Duke of Clarence and the Princess Charlotte.

The second dance may have been to the tune of Miss Johnston, but identifying that tune requires a little detective work; dozens of tunes had been published that might credibly be identified, mostly in Scotland. There were a group named for Miss Johnston of Hillton (who may in fact have been the same person as our Miss Johnston), several for Miss Louisa Johnston, several for Miss Mary Ann Johnston, Lady Jemina Johnston, and Miss Mary Johnston; several more were named as Miss Johnston's March, Waltz, Reel, Fancy or Strathspey.

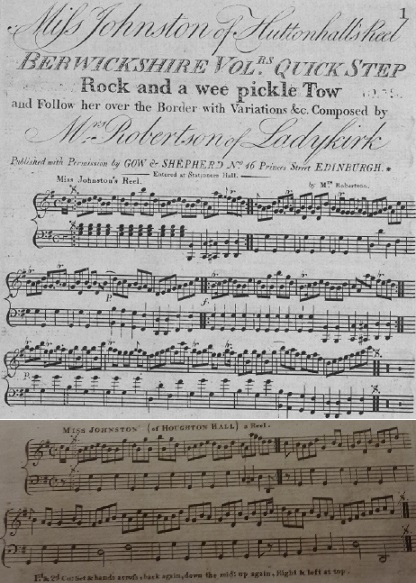

To resolve the uncertainty we can look to the London publications. A dozen or more of London's music sellers issued versions of the same tune between about 1805 and 1808, the name of which was some variant of Miss Johnston of Houghton Hall's Reel. Some named it for Miss Johnston , others for Miss Johnson , and some even for Miss Johnstone ; some made her a resident of Houghton Hall , others of Houton Hall ; some included or omitted the suffix of Reel , some named her as Mrs rather than Miss . But each variant was essentially the same tune, a melody seemingly not to be found amongst the old Scottish dance collections; it instead derives from a c.1802 Edinburgh publication issued by Gow & Shepherd named Miss Johnston of Huttonhall's Reel, the composition of which was credited to Mrs Robertson of Ladykirk (see Figure 7). The Johnstons of Huttonhall (or Hutton Castle) can be identified; they were in decline at the start of the 19th Century, their family titles were dormant and their name was in the process of fading.

We've animated an arrangement of the double figures set by Thomas Wilson in his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore (to the 1807 music offered by George Walker), and the c.1807 arrangement by Button & Whitaker.

It was a Scottish tune, but seemingly one of recent composition. The Gow in Gow & Shepherd was Nathaniel Gow, he represented the Gow family interests in Edinburgh; his brother John Gow did the equivalent in London. This small publication was to be had of John Gow, No 31 Carnaby Street, Golden Square, London . It was clearly within the repertoire of the Gow band; most London references to Gow were probably to John, but both of the brothers were celebrated Violinists and Orchestra leaders; one of them would lead part of the music at our 1813 Ball. They presumably promoted the tune, and experienced the good fortune of having it become popular in London c.1805, after which it was published by many of the other London vendors.

London publications of the tune include Dale's c.1805 8th Number, Goulding's c.1806 8th Number, Skillern & Challoner's c.1806 2nd Number, Campbell's 1806 21st Book, Button & Whitaker's c.1807 6th Number (see Figure 7), Walker's 1807 13th Number and James Platts's c.1808 4th Number. Nathaniel Gow reprinted the tune in Edinburgh in his 1809 A 5th Collection of Strathspeys, Reels &c.

References to the tune being enjoyed in polite society include the Perthshire Hunt Ball for 1809 at which John Bowie (the band leader) used it for the first dance (Perthshire Courier, 9th October 1809), The Duchess of Gordon's Ball (Morning Post, 8th March 1806), Sir Windsor and Miss Hunloke's Ball (Morning Post, 24th March 1806), Mr M.P. Andrew's Grand Ball (Morning Post, 2nd May 1806), The Mansion House Ball (Morning Post, 1st April 1807) and Mrs Boehm's Ball which opened with Miss Johnstone, of Hutton-hall (Morning Post, 23rd May 1807). It may also have been used at The Princess of Wales's Ball and Supper in 1809 at which that admirable dance called Lady Lucy Johnstone was enjoyed (a tune I can't identify if it's not our tune). The single most prestigious appearence of the tune was as one of only two dances at the 1811 Carlton House Ball that celebrated the commencement of The Regency, it was clearly a favourite tune.

The composer was Mrs Robertson of Ladykirk, the Robertsons must have been friends of the Gows, several Gow family tunes reference them; examples include Mr Robertson of Ladykirk's Strathspey, Mrs Robertson of Ladykirk's Favorite, Ladykirk House and Rattling Roaring Willie, or Mr Robertson of Ladykirk's Delight. What must Mrs Robertson have thought had she known that the Royal family were dancing to her tune in London?

For futher references to the tune, see also: Miss Johnston (1) at The Traditional Tune Archive

The Prince Regent

The third dance was The Prince Regent, led off by the Duc de Berri and Princess Charlotte.

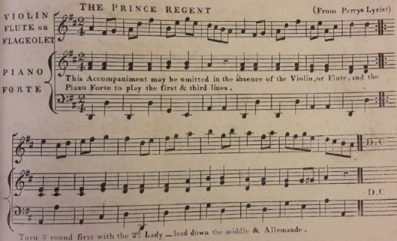

The Prince of Wales was appointed Prince Regent in 1811, dozens of tunes were named in reference to this event, the tunes were effectively dedicated to the Prince, though probably without his knowledge. All of London's music publishers would have had tunes of this name in their catalogues. I've been unable to conclusively demonstrate which of those tunes was used at our Ball, at least one of the tunes was clearly accepted by the Prince and was danced in his honour in 1813.

Another Ball at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton in 1817 featured a tune of the same name (Oxford University and City Herald, 11th January 1817), if it was the same tune then it must have remained in circulation for several years. Several further Balls featured a Regent's Medley which could have included our tune (but probably didn't).

Three strong candidates for the tune emerge, each of which was published in London more than once somewhere around 1812 or 1813.

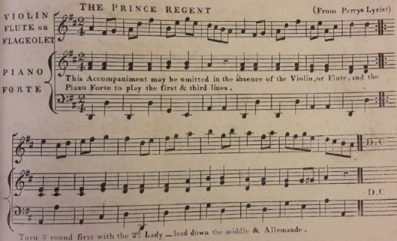

Figure 8. One of our candidate The Prince Regent tunes by John Parry, from the c.1813 Goulding & Co's Collection of New & Favorite Country Dances, Reels & Waltzes. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.a.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

-

The first of the tunes to consider was composed by John Parry and was available from the Goulding and Davie stores (and perhaps elsewhere) from perhaps 1812. Parry was a successful composer of Country Dancing tunes, he composed several of the

hit tunes of 1809 and 1810, we've discussed his The Persian Dance in a previous paper. It's entirely plausible that his tune would have been introduced to a Royal audience, and would go on to be danced socially before being widely published. We've animated an arrangement of the version that Parry printed through Goulding & Co c.1813 (see Figure 8).

-

A second tune was issued by both Skillern & Challoner and Button & Whitaker (and probably others) around 1812. Both publishers had a reputation for high quality publications, ordinarily I'd have expected them to issue the most correct version of a tune. We've animated an arrangement of the Skillern & Challoner version from their c.1812 17th Number.

-

A third candidate was issued by Charles Wheatstone from around 1813 in several publications. He added a subtitle:

danced at his fete . Wheatstone intended his readers to know that he had a tune that the Prince Regent himself had made use of. I'm not entirely convinced that Wheatstone would have secured the most prestigious tune of this name for himself, especially at this slightly later date, but it's certainly possible. We've animated an arrangement of the Wheatstone & Voigt version from their c.1813 8th Book.

A case could be made for any of these tunes having been used. Some of them sound more Scottish than others, but none of them may in fact have been so.

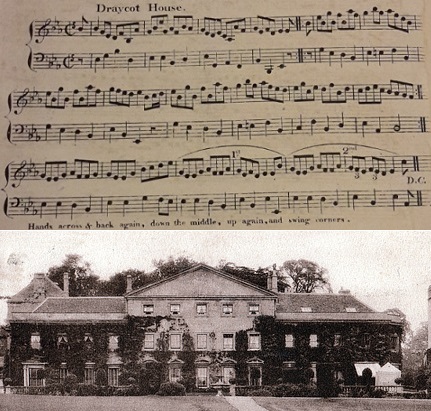

Draycot House

The fourth dance was Draycott-House, which was led off by the Duke of Clarence and Princess Mary.

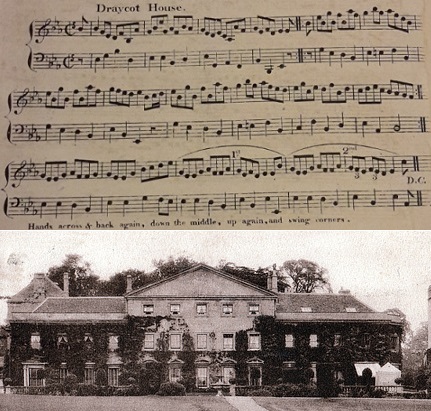

Draycot House in Wiltshire (see Figure 9) was the home of the Tylney Long family; The Times newspaper for 5th October 1810 reported that A magnificent dinner was given on Wednesday at Draycot-house, by Lady Tilney Long, in honour of her daughter's coming of age. ... It is computed that upwards of 5000 persons were present. The festivities will continue the whole of the week . The tune may have been named in tribute of (and perhaps also composed for) this magnificent party.

Figure 9. Draycot House from William Dale's c.1812 19th Number (above), and an early 20th century view of the (now demolished) Draycot House (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Less than two years later the young and fabulously wealthy heiress Catherine Tylney-Long (1789-1825) married William Wellesley-Pole (1788-1857) (nephew of the future Duke of Wellington) in March 1812, it was one of the most significant weddings of the year. Our Draycot House tune was circulating from around 1811 so it was probably named in reference to the party, it may have become popular in reference to the wedding. Catherine was reputed to be both the richest woman in England and also the richest commoner in England, later commentators would describe her as The Wiltshire Heiress . It's possible that the couple were in attendance at our Ball.

A few references to the tune at society events are known from 1812 forwards; it was reported of Lady Caroline Barham's Ball (Morning Post, 22nd June 1812) that a Draycott House medley was danced; and of Lady Sarah de Crespigny's Masked Ball (Morning Post 15th January 1814) that at eleven dancing commenced to the tune of Draycot-house . Versions of the tune were issued by William Campbell in his c.1811 26th Book, William Dale in his c.1812 19th Number (see Figure 9), Halliday & Co in their c.1812 10th Number, James Platts in his c.1812 33rd Number and Christopher Gerock in his 24 Country Dances for the year 1813; some publishers issued a tune named Draycot Lodge that may have been the same, examples include Button & Whitaker in their 1813 23rd Number. Most of the published editions of the tune were identical, including the associated dancing figures; it's likely that the publishers copied it from each other, if the tune was widely known then I'd expect more variety to appear amongst the publications.

Draycot House seems not to have been an especially popular tune, it was probably danced in tribute to the recently married couple but it would soon go on to be forgotten. We've animated an arrangement of William Dale's c.1812 version of the dance, and also of James Platts's c.1812 version.

Largo's Fairy Dance

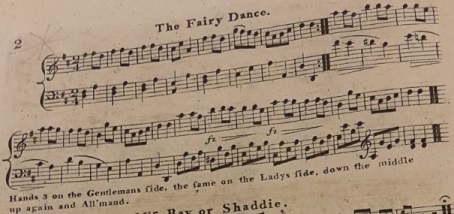

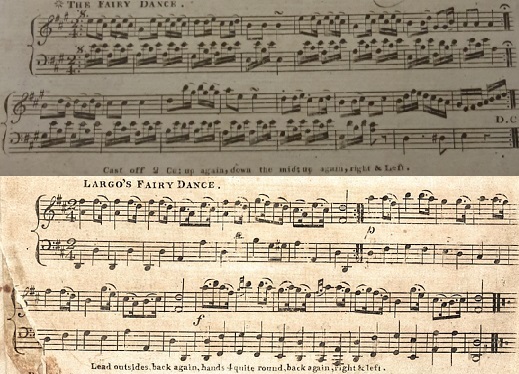

At the conclusion of this dance the Band struck up the Fairy Dance.

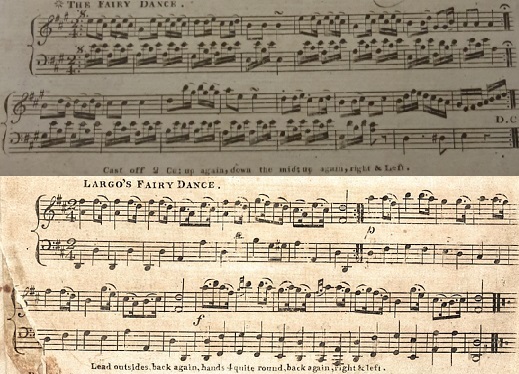

The first half of the Ball ended with the Fairy Dance, it's not clear whether they danced to the tune, but it was a very popular dancing tune at the time, it seems likely that they did. The Fairy Dance was widely published from around 1808, and widely referenced as having featured at the balls of the Nobility.

The story of this tune is a little more complicated however, the tune is easily identified but the composer is not - there were two opposing parties who both claimed it as their own. The right to ownership might have been valuable... at least the rights to such tunes were starting to become valuable, I've no evidence that Country Dance publishers actually sued each other over copyright violations quite as early as 1807, though they certainly might do so by 1813. There were hints that an action might be pursued, with declarations of intent issued in the press.

We know the tune was used socially; the initial such reference involves The Countess of Powis's Ball (Morning Post, 19th June 1807) where The dances recommenced at three, with The Largos; or Fairy Dance. It was not until six o'clock that the whole concluded with reels. Mr Gow, and Mr Nathaniel Gow, from Edinburgh, were present; the music, which was under their direction, was sprightly and good . This Ball featured both Gow brothers and our tune. A few weeks later it was reported of Mrs and the Miss Thompson's Ball (Morning Post, 11th July 1807) that The Largos Fairy Dance, composed by Mr Nathaniel Gow, of Edinburgh, continued a favourite throughout the evening . Nathaniel evidently identified himself as the composer at this early date. Further references include Mrs Boehm's Ball (Morning Post, 8th April 1808), Mrs Knox's Ball (Morning Post, 19th May 1808), Mrs Thomas Smith's Ball (Morning Chronicle, 25th June 1808), The third High Wycombe Assembly (The Globe, 15th November 1808), The Lord Mayor's Ball (Morning Chronicle, 16th January 1809), Mrs Beaumont's Grand Ball and Supper (The Globe, 17th April 1809), and so forth. A further five such balls are known to have featured the tune in 1810, but references are much less frequent thereafter, it may have been falling from fashion by 1813. Many of these Balls are known to have had the Gow band present, probably the London branch of that band under John Gow.

It might appear certain that Nathaniel Gow was the composer of the tune, he certainly received recognition for having done so. The rival claim was made on behalf of James Sanderson; Sanderson was a prolific composer for the London stage, over 150 productions were said to have been his work. His stage tunes, if sufficiently catchy, could transition into use for Country Dancing (often without attribution). He was responsible for an 1806 pantomime named Guy of Warwick that was performed at the Royal Amphitheatre, Westminster Bridge; the overture included The Fairy Dance, as reviewed in The Monthly Magazine for June 1806. The overture was published through Button & Purday, shortly thereafter they would issue a rondo arrangement of The Fairy Dance, now Performing with universal applause in the Pantomime of Guy of Warwick. Their major attack on the Gow claim was launched the following year, they issued a statement printed in The Star for 3rd July 1807 that read as follows:

The Fairy Dance - Messrs Button and Purday, No 75, St Paul's Church yard, respectfully inform the public that the above popular Air, which has been danced by all the late Fashionable Parties, is published either as a Rondo or Country Dance, by them only. They also take this opportunity of informing the trade, that having paid Mr Sanderson, the composer of this Air, a considerable sum for the Copy-right of it, they are determined to defend their property to the utmost; and therefore, should the two individuals who have announced their intention of issuing piratical Copies of it, persist in such publication, an action will be immediately commenced against each of them.

The two individuals that were threatened were presumably the Gow brothers, Nathaniel and John. We've animated an arrangement of the Sanderson tune as published by Button & Purday in 1807.

Figure 11. The Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's 1807 7th Number (above), and Largo's Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

The truth of the matter may involve a case of mistaken identity. Button & Purday (later Button & Whitaker) owned the rights to a tune called The Fairy Dance composed by Sanderson, they published a country dancing arrangement of it in their 1807 7th Number (see Figure 11, top) and it clearly achieved some degree of success. The Gows had independently named a different tune by the same name and promoted it at society Balls; Button & Purday issued their cease-and-desist notification in the mistaken belief that their tune was being appropriated by the Gows. But their next publication, the c.1808 8th Number included a tune they called Largo's Fairy Dance (see Figure 11, bottom), it was somewhat different to their first tune and carried no such copyright declaration. This second tune was widely published in London in 1808 under the simpler name of The Fairy Dance, it is this tune that was claimed by the Gows. I've identified copies of this second tune issued by around a dozen London publishers c.1808 (including Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 5th Number, see Figure 10), but only one other copy of the first tune (published by Michael Kelly in a collection of New Dances for 1808). Nathaniel Gow would go on to publish this second version of the tune twice in Edinburgh in 1809, claiming in one publication to have originally composed it for the Fife Hunt Ball of 1802. We might speculate that the Gows had a strongly worded conversation with Button & Purday after receiving notification of the threatened action, and the situation was thereby resolved; perhaps the prefix of Largo (a parish of Fife) had been applied to the Gow tune in an attempt to avoid ambiguity. If so, it failed; the simpler name of The Fairy Dance was almost universally used for the Gow tune. The term Largo is especially confusing as it usually implies a slow passage of music, it's a term that can be found at the very start of the main overture of Button & Purday's publication of Sanderson's score. Button & Co may have interpreted Largo as clear evidence of their tune being used.

So perhaps the mystery is solved, two tunes were issued under essentially the same name; our tune of 1813 was the version promoted by the Gow family, it was widely printed in London c.1808 and then in Edinburgh c.1809, it was said to have been composed in 1802. That stated, I remain in some doubt over the dispute; the Largo equals Fife back-story feels a little contrived, and would Nathaniel Gow really have allowed a commercially successful tune that he'd composed in 1802 go unpublished under his own name until 1809 (especially while it was actively published and danced to in London from 1807)? The Gows clearly wanted their critics to accept their chosen narrative, but doubts linger. Could Largo's Fairy Dance have been introduced in the days immediately following the Button & Purday complaint, with an invented origin story added later, in order to confuse the historical record and to provide a plausible defence? If so, it worked; the new tune appropriated the existing name and the Sanderson tune was largely forgotten.

We've animated an arrangement of the Gow tune as published by Skillern & Challoner c.1807 (see Figure 10) and of the c.1808 Button & Whitaker version.

The legal posturing of Button & Purday was a foreshadowing of what was to come. London's country dance publishing industry became mired in legal disputes in the 1810s, various publishers sought to protect their tunes from unauthorised reproduction, in so doing they may have hastened the end of their industry (it collapsed towards the end of the 1810s). Regardless of the confusion over its origins, we can be reasonably certain of which tune was being enjoyed at our 1813 Ball.

For futher references to the tune, see also: Fairy Dance at The Traditional Tune Archive

Polonaise Grand March

a Band, appropriately stationed, struck up "God save the King"; which was followed by a Russian march, in compliment to the Russian Ambassador.

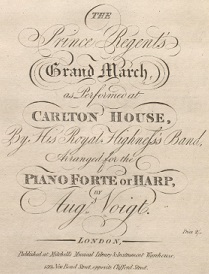

Figure 12. c.1811 The Prince Regent's Grand March by Augustus Voigt. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.443.o.(2.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

It's not clear from the source information as to whether the March was merely played, or was danced. A Polonaise or Grand March is a form of elegant movement more associated (at least in Britain) with the reign of Queen Victoria; it would be unusual to experience a March at this early date, though it's plausible when introduced in compliment to the Russian Ambassador (and perhaps more honestly, in compliment to the future star of international diplomacy, his wife the Countess Dorothea Lieven).

A Polonaise march is sometimes used to move people from one room to another; it may involve couples elegantly promenading their way through the various state rooms of a palace before reaching the Ball Room, perhaps accompanied by a band along the route. The couples may then be directed to separate and proceed around the ball room in elegant patterns while the rest of the party catch up. The word Polonaise literally implies a Polish dance, it derives from the dancing of the Russian court. The first clear evidence I have for Polonaise marching at a British ball dates from two years after our event; the British delegation to the 1814 Congress of Vienna (in Austria) in January 1815 hosted a grand ball in celebration of Queen Charlotte's Birthday (Morning Post, 13th February 1815): At ten the Emperor of Russian opened the Ball ... [by] ... polonaising from the State Room, through the extensive suite of apartments. The assembly being en grande costume , displayed one of the most animated scenes of splendour and beauty ever witnessed. Waltzes, French Country-dances, and Quadrilles succeeded to the Polonaise. In other apartments some of our most admired English national airs struck up, and were danced with unequalled spirit. . There are hints that polonaise marching was experienced at the Royal Pavilion (Brighton) in 1817 (e.g. Morning Chronicle, 20th January 1817), by 1818 several of London's dancing masters advertised tuition in La Grand Polonaise. The Polonaise March probably came to the attention of British dancers after its success at the grand balls of the Congress of Vienna.

Several tunes purporting to be Grand Marches were published in dedication to the Prince Regent c.1811, it's possible that one of them was used at our Ball. Examples include Augustus Voigt's c.1811 The Prince Regent's Grand March as Performed at Carlton House, by His Royal Highness's Band (see Figure 12), and Blewitt's c.1811 The Prince Regent's Grand March and Waltz.

A royal palace is precisely the type of venue where a Polonaise march might be used to transfer the guests back to the Ball Room from supper, our 1813 Ball might have featured an early example, perhaps even the first the country had experienced. One can almost imagine the Russian Countess applying her infamous charm to persuade the Regent to lead the guests back upstairs using a Polonaise march; she is widely credited with having promoted the Waltz dance in London at around the same date. A March offers a means by which all of the guests may participate in the dancing, regardless of experience (or even inclination), the marching couples may resort to mere walking without problem. There again, the Russian march may simply have been some rousing music to awaken the company following the (possibly 3am) speeches; marching music was often used to accompany the general promenading that might be expected at a Ball, our Russian march may have been no more than that.

Figure 13. Because he was a Bonny Lad from Goulding's c.1812 31st Number. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.dd ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

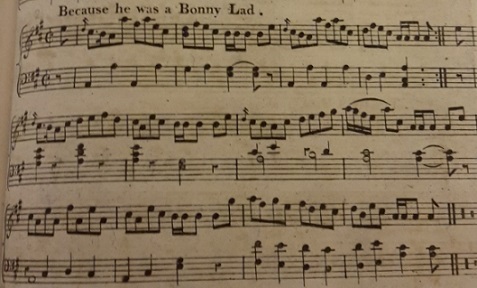

Because he was a Bonny Lad

the first dance was led off by the Duke of Clarence and the Princess Charlotte, to the tune of Because he is a bonnie Lad

This tune is readily identifiable as an old Scottish tune variously known as Because he was a bonny Lad, Because I was a bonny Lad, The Bonny Lad, etc.. It had been published many times in both Edinburgh and London across the 18th Century and into the early 19th Century. Examples of publication in London include Goulding's Collection of 24 Country Dances for 1797, Dale's c.1804 4th Number, Goulding's c.1812 31st Number (see Figure 13), and Cahusac's Collection of 24 Country Dances for 1814. The tune had featured at royal balls since at least 1795 when it was danced at an event celebrating the wedding of the Prince and Princess of Wales (The Ipswich Journal, 25th April 1795). I can't identify any other society Balls to feature this tune, but it had been known in London since the first half of the 18th Century when it appeared in the Walsh country dance collections, it reappeared a little later in both the Thompson and Rutherford collections. It was a veteran tune, it must have remained somewhat popular across several generations of dancers; it was perhaps rediscovered by fashionable society of the early 19th Century, but it wasn't a new tune.

We've animated an arrangement of the Goulding figures from 1797 using the Goulding music from c.1812 (the later music includes a bass accompaniment that was absent from the version printed 15 years earlier, see Figure 13); and also an arrangement of Dale's c.1804 version.

For futher references to the tune, see also: Because He was a Bonny Lad at The Traditional Tune Archive

Fight about the Fireside

which was followed by Fight about the Fire-side

This was another tune that was widely published under a variety of slightly different names, alternative variants include Fight about the Fire Side and Fight about the Fire. The earliest version I'm aware of was published in London in the Bride collection of 24 Country Dances for the Year 1767; it then went on to be published in Edinburgh by Robert Mackintosh in his c.1796 3d Book of Sixty Eight New Reels and Strathspeys; it was also published by Niel Gow in his 1799 Part First of the Complete Repository of Original Scots Slow Strathspeys and Dances. It would be followed by a burst of interest in London around the start of the 19th Century, Nathaniel Gow went on to publish a version himself in 1822. Figure 14 shows a c.1805 version of the tune published by Abraham Mackintosh of Newcastle. Early London publications include William Campbell's 1801 16th Book, and Robert Mackintosh's c.1803 A Fourth Book of new Strathspey Reels.

Examples of the tune being danced socially include the Countess of Leicester's Ball of 1800 (Caledonian Mercury, 27th March 1800), The Duchess of Chandos's Ball of 1802 (Morning Post, 26th April 1802), Mrs Malcolm's Ball of 1802 (Morning Post, 14th June 1802), Mrs and the Miss Thompson's Ball of 1807 (Morning Post, 11th July 1807), Lady Saltoun's Ball of 1809 (Morning Post, 1st July 1809), the Perthshire Hunt Ball of 1809 (Perthshire Courier, 9th October 1809), and Mrs Crawford Bruce's Ball of 1810 (Morning Post, 22nd January 1810). Occasional passing references to the tune can be found in print thereafter.

It seems that the tune remained popular for over a decade. We've animated arrangements of the version in Thomas Budd's 1801 31st Book and Nathaniel Gow's 1822 version.

For futher references to the tune, see also: Fight About the Fireside at The Traditional Tune Archive

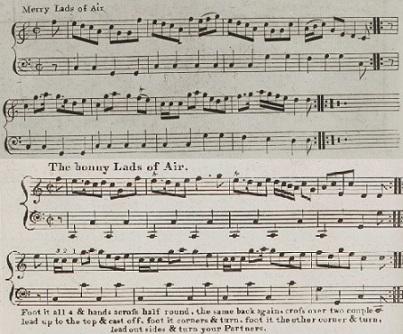

Figure 15. Merry Lads of Air from Robert Bremner's 1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances (above), and The bonny Lads of Air from Dale's c.1809 15th Number (below). Upper image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland, lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

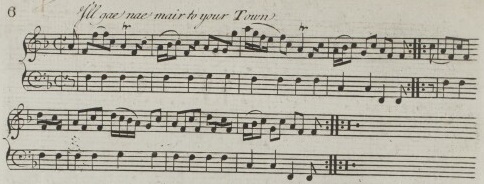

The Merry Lads of Ayr

after which The Lads of Ayr

This tune was variously known as The Lads of Ayr, The Merry Lads of Ayr and The Bonny Lads of Ayr, some editions spell Ayr as Air . It's another Scottish tune, Niel Gow credited the original composition to John Riddle, the earliest publication I can find is that of Robert Bremner c.1757 (see Figure 15). It was published many times in London over the decades, examples issued between the 1760s and 1790s can be found within the Bride, Rutherford and Longman country dance collections. There was a burst of publishing interest in the tune between about 1808 and 1810 when several London publishers issued copies; the first of that late group was probably William Campbell in his c.1808 23rd Book, it was followed by Dale's c.1809 15th Number (see Figure 15), Goulding's c.1810 19th Number and Wheatstone's c.1810 5th Book.

The late publishing bubble coincided with several references to the tune being enjoyed at society balls. It was reported of Mrs Boehm's Ball (Morning Post, 8th April 1808) that the second dance was Bonny Lads of Ayr ; 15 couples danced to the tune at Lady Campbell's Ball (Morning Post, 15th June 1810), it was also danced at Lady Mary Lindsey Crawford's Ball (Morning Post, 11th June 1810) and was the first dance at Mrs and the Misses Thompson's Ball (Morning Post, 14th July 1810). Presumably the tune was still current at the date of our 1813 ball. We've animated an arrangement from Wheatstone's c.1810 5th Book and of Dale's c.1809 version (see Figure 15).

For futher references to the tune, see also: Merry Lads of Ayr (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

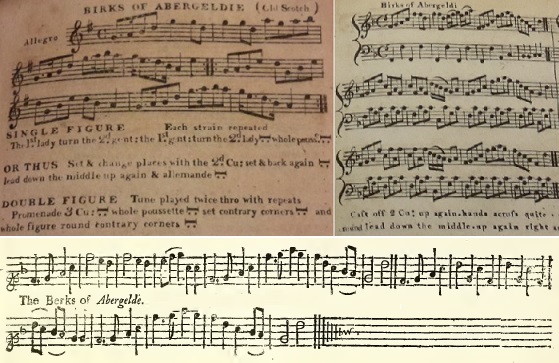

The Birks of Abergeldie

and concluded with The Birks of Aberdeen

There's a mild mystery involved with this tune as The Birks of Aberdeen is not a name that's known from the published collections. Luckily the Morning Chronicle newspaper resolves the uncertainty, its report of the ball (8th February 1813) gave the name of this final tune as The Birks of Abergeldie and added the detail that her Royal Highness danced with Earl Delawar . The Birks of Abergeldie (variously spelled with Berks , Abergelde , Abergeldy and other variants) was a veteran Scottish tune; it was widely published in London by the start of the 19th Century.

Figure 16. Birks of Abergeldie from Thomas Wilson's 1816 Companion to the Ball Room (left), Birks of Abergeldi from Fentums's Sixteen New Country Dances for the Year 1796 (right), and The Berks of Abergelde from Playford's 1700 A Collection of Original Scotch-Tunes. Right image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, a.222.b.(3*.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Versions of the tune were issued in London from at least as early as 1700 in Henry Playford's A Collection of Original Scotch-Tunes (see Figure 16), numerous versions were printed towards the end of the 18th Century and the start of the 19th. The Thompson dynasty included the tune in their c.1765 second volume Compleat Collection of 200 Favourite Country Dances under the name The De'els Dead . Longman & Broderip printed a version in their c.1793 3rd Selection, John Fentum in his 16 New Country Dances for the year 1796 (see Figure 16), Bland & Weller in their collection of 24 Country Dances for 1800, the shops of Davie, Dale and Andrews all issued copies too; Thomas Wilson choreographed figures for the tune in both his 1809 Treasures of Terpsichore and 1816 Companion to the Ball Room (see Figure 16); it can also be found in the Cahusac collection of 24 Country Dances for 1814. It was also published in Scottish collections such as Aird's third volume of 1788 and Robert Petrie's collection of 1796. There was no sudden burst of publishing interest in the tune, just an ongoing mild interest over several decades. The same tune was featured at another Royal Ball later in 1813 (Morning Post, 14th May 1813) under the name Birks of Abergilvie.

The mystery of the tune having been named at our ball as The Birks of Aberdeen may be related to a further alternate title that was in use for the tune. I'm indebted to Louise Siddons for the observation that the tune was published in Dublin within John and William Neal's c.1726 Choice Collection of Country Dances under the name Aberdeen, or The Deils Dead .

We've animated an arrangement of the c.1793 Longman & Broderip version, and an arrangement of Thomas Wilson's 1816 Double Figure (see Figure 16) to the 1796 Fentum music. The Wilson arrangement is a little unusual as it includes the uncommon whole figure round contrary corners figure.

For futher references to the tune, see also: Birks of Abergeldie (The) at The Traditional Tune Archive

Conclusion

If you'd like to recreate a Royal Ball of early 1813 we have a suitable programme. Have your guests arrive in time for an 11pm start, then dance four or five Country Dances through to 1am. Break for supper and speeches, a stirring round of the National Anthem, then a grand march back to the Ball Room (to show your palatial state rooms at their finest); four more Country Dances should see the party through to 5 or 6am. By then the crowds should have mostly departed and the guests may seek their carriages in peace.

You'll want the dance floor to be chalked with suitable (probably heraldic) imagery, the ladies should sport ostrich feathers in their hair, the men should wear their military uniforms. The most prestigious band of the era should be in attendance with an orchestra of 14, and grand illuminations should be prepared. A banquet for around 60 to 65 close friends should be served, and less intimate arrangements made for the rest of the party. Guardsmen and other security professionals should be stationed nearby. Add a little tabloid and political sensationalism to ensure that your party is talked about for weeks to come.

Of course if your ambitions are a little less lofty, the tunes we've written about will be an eminently suitable ornament to any modern recreation of a Regency Ball. You can dance to the tunes using any figures you like (the published examples will tend to be suitable), just ensure that all of your guests have a great time. The tunes at the 1813 ball were mostly Scottish in theme, some were of recent composition but many were old favourites that had been known (and perhaps also forgotten) for decades. It's unusual to discover such a complete list of tunes for a single event, but it's probably representative of the repertoire that would have been experienced at any high society ball at that date (though perhaps not of an Assembly Room Ball or other types of event). Most of the guests would not have been dancing, many were there just to mingle and enjoy the entertainment, maybe as few as 12 couples would have danced some of the dances.

We'll leave this investigation here, if you have any further information to share do please Contact Us as we'd love to know more!

|

Figure 2. Queen Charlotte c.1789 (above, left); King George III c.1799 (above, right); Princess Caroline c.1820 (below, left); Prince Regent c.1816 (below, right)

Figure 2. Queen Charlotte c.1789 (above, left); King George III c.1799 (above, right); Princess Caroline c.1820 (below, left); Prince Regent c.1816 (below, right)

Figure 3. Rooms of Carlton House. Entrance Hall (above), Conservatory (middle), Gold Room (below), Grand Staircase (right). Images from Pyne's 1819 The History of the Royal Residences.

Figure 3. Rooms of Carlton House. Entrance Hall (above), Conservatory (middle), Gold Room (below), Grand Staircase (right). Images from Pyne's 1819 The History of the Royal Residences.

Figure 4. The Circular Room or a Squeeze at Carlton Palace, 1825 (the Palace was considered to be too small, it was demolished in 1826 and the nearby Buckingham Palace would become the home of the Monarch)

Figure 4. The Circular Room or a Squeeze at Carlton Palace, 1825 (the Palace was considered to be too small, it was demolished in 1826 and the nearby Buckingham Palace would become the home of the Monarch)

Figure 5. I'll gang na mare to yon town, from Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 15th Number. Image courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), EFDSS.

Figure 5. I'll gang na mare to yon town, from Skillern & Challoner's c.1812 15th Number. Image courtesy of the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library (VWML), EFDSS.

Figure 6. I'll gae nae mair to your Town, from Robert Bremner's 1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances. Image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

Figure 6. I'll gae nae mair to your Town, from Robert Bremner's 1757 A Collection of Scots Reels or Country Dances. Image courtesy of Historical Music of Scotland.

Figure 7. c.1802 Miss Johnston of Huttonhall's Reel by Mrs Robertson of Ladykirk (top), and Miss Johnston (of Houghton Hall) a Reel from Button & Whitaker's c.1807 6th Number (below). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 7. c.1802 Miss Johnston of Huttonhall's Reel by Mrs Robertson of Ladykirk (top), and Miss Johnston (of Houghton Hall) a Reel from Button & Whitaker's c.1807 6th Number (below). Lower image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 8. One of our candidate The Prince Regent tunes by John Parry, from the c.1813 Goulding & Co's Collection of New & Favorite Country Dances, Reels & Waltzes. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.a.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 8. One of our candidate The Prince Regent tunes by John Parry, from the c.1813 Goulding & Co's Collection of New & Favorite Country Dances, Reels & Waltzes. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, b.55.a.(6.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Figure 9. Draycot House from William Dale's c.1812 19th Number (above), and an early 20th century view of the (now demolished) Draycot House (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 9. Draycot House from William Dale's c.1812 19th Number (above), and an early 20th century view of the (now demolished) Draycot House (below). Top image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.q ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 10. The Fairy Dance from Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 5th Number.

Figure 10. The Fairy Dance from Skillern & Challoner's c.1807 5th Number.

Figure 11. The Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's 1807 7th Number (above), and Largo's Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Figure 11. The Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's 1807 7th Number (above), and Largo's Fairy Dance from Button & Whitaker's c.1808 8th Number (below). Upper image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, g.230.aa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.