English Regency Dances, Costumes, Balls, Etiquette, Lessons and Music

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

(Advertise your events here for free)

This site uses cookies

| Return to Index | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Paper 10 James Paine, of Almack's (1778-1855)Contributed by Paul Cooper, Research Editor [Published - 16th January 2015, Last Changed - 9th February 2023]James Paine was a band leader, Quadrille publisher, and music seller of the Regency era. He is best known as having been an orchestra leader at the most prestigious of Regency dancing venues Almack's Assembly Rooms in London, and for publishing his various Sets of Quadrilles. His First Set of Quadrilles remain known to this day. In this article we'll explore his life, and his contributions to the social dancing experience of the 1810s and 1820s.

Paine's Family

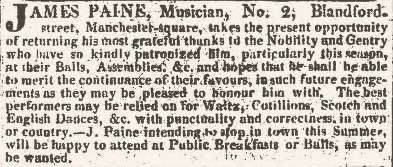

I've experienced limited success in researching Paine's early life, though some information can be recovered from the International Genealogical Index (IGI). We can estimate that he was born in 1778 based on his reported age in the 1841 and 1851 census records. His life remains vague until he was married to the 18 year old Elizabeth Riebeau in 1804; her family ran a book-binding business, presumably Paine was from a similarly successful professional family. The 1805 insurance records at the Sun Fire Office describe Paine as  Figure 1. James Paine's advert, The Morning Post 7th August, 1811.

Figure 1. James Paine's advert, The Morning Post 7th August, 1811. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) Paine's contact address during the early stages of his career was shared with the Riebeau business at 2 Blandford Street, Manchester Square (see Figure 1). This address is where George Riebeau had his variously titled stationers, book-binders, circulating library, and/or book-sellers. George was presumably either James' Father-in-law, or his Brother-in-law. James and Elizabeth named their first son George Riebeau Paine, so George was probably Paine's Father-in-law. George Riebeau is better known to history as the first employer of a young Michael Faraday. Faraday was apprenticed at 2 Blandford Street during the same period that Paine used it as his business address, it's probable that they knew each other. It was here that the aspiring Faraday was enabled to study scientific publications, while Paine would have received inquiries for his musical services.

James and Elizabeth had nine children together before she died in child-bed in November 1820. She was survived by her infant son, William. James described himself in his notification in The Morning Post (27th November, 1820) as One of their children, Charles Frederick (born 1816), experienced some form of medical complications. James made special provision for Charles in his Will, it required his remaining children to provide for his maintenance and support for the rest of his natural life. He presumably required special care, perhaps at an institution. According to the Census records, Charles was still living with his father in 1851. James Paine died in 1855. His Will is available through the National Records Office. It reveals that he was relatively wealthy by the time of his death; he owned seven properties, shares in a copper mine, and the stock of his music shop; he distributed a further £1500 amongst his children in cash. This is in stark contrast to the approximately £130 that Joseph Hart (another popular band leader of the 1820s) left to his dependants, as we saw in a previous paper.

Paine's Band Figure 2. A detail from The Cyprian's Ball at the Argyll Rooms, Cruikshank, 1825.

Figure 2. A detail from The Cyprian's Ball at the Argyll Rooms, Cruikshank, 1825.

Paine had been elected to the Royal Society of Musicians in 1809, he was evidently a successful musician by this date. The first reference I've found to Paine's band is from The Morning Post newspaper in 1811 (7th August, see Figure 1). That advert reads: It's clear that he was already an accomplished musician by 1811, he had access to both a band and engagements. I've not found any information about his band prior to 1811 but they were regularly mentioned in newspapers between the years 1811 and 1828.James Paine, Musician, No 2 Blandford-Street, Manchester-square, takes the present opportunity of returning his most grateful thanks to the Nobility and Gentry who have so kindly patronized him, particularly this season, at their Balls, Assemblies &c. and hopes that he shall be able to merit the continuance of their favours, in such future engagements as they may be pleased to honour him with. The best performers may be relied on for Waltz, Cotillions, Scotch and English Dances, &c. with punctuality and correctness, in town or country. J. Paine intending to stop in town this Summer, will be happy to attend at Public Breakfasts or Balls, as may be wanted.

The 1811 advert above didn't mention Almack's Assembly Rooms, his high-profile employer of subsequent years. He probably wasn't employed at Almack's at such an early date, though he certainly was from 1816 when he began publishing Quadrille Sets under the name On the Regent and the Queen's return from the water side, Mr. Paine of Almacks, with a most excellent and numerous band, was in readiness, and as soon as her Majesty had taken her seat in an arm chair prepared for her, dancing commenced by the junior branches of the distinguished personages present, consisting of the Ladies Stanhope, Ladies Bathurst, and others. They commenced with a quadrille; the second was a waltz, and the third a waltz.

That engagement came a few days after he had played at another royal event: Princess Elizabeth's Fete. We know that the Fete was important to Paine as he sent a correction to the editor of The Morning Post newspaper (published 8th August 1817) concerning it. Paine was distressed that they had wrongly reported that John Gow's Band was present, his letter emphasised that his band had in fact played. He signed himself James Paine, rather than

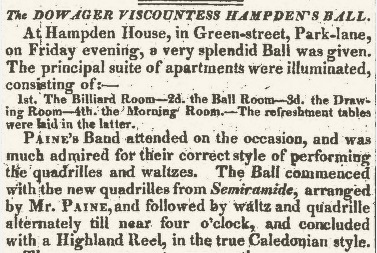

References to Paine's band emerge from as early as 1811. He led the music at an important Ball and Supper hosted by Lady Borpingdon in 1811 (The Morning Post, 9th May 1811):  Figure 3. Viscountess Hampden's Ball, The Morning Post 10th April, 1826.

Figure 3. Viscountess Hampden's Ball, The Morning Post 10th April, 1826. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The Times newspaper in 1813 (8th July 1813) reported on The Prince Regent's Gala,

The band would also travel when requested; they were commissioned to play at both Petworth House in Sussex, and Powys Castle in Wales, in 1824; also at Epsom and Maidenhead in 1826. They played at several balls in Cambridge in 1819. An 1823 account in Knight's Quaterly Magazine mentions

Two of the named musicians we know Paine sometimes worked with were John Michael Weippert and Hubert Collinet. According to the 1883 A History of the Municipal Paine and Weippert were both associated with a Ball at Reading in 1819:

References to Paine's band seem to disappear from around 1828. The penultimate occasion at which I've found them mentioned is from The Morning Post (15th July 1828) where they are said to have played at Mr. Penn's Dancing, which commenced at ten o'clock, was continued, with the interval of supper, until six this morning, with the greatest spirit, under the direction of Mr. J. Banister, as Master of Ceremonies. The floor of the Hall was chalked with appropriate devices, and the pillars and other parts tastefully decorated. The supper was provided by Mr. Clarke, of the White Hart Inn, in his best style. Paine's band attended.

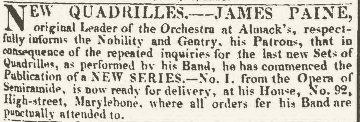

Figure 4. New Quadrilles, The Morning Post 4th May, 1826.

Figure 4. New Quadrilles, The Morning Post 4th May, 1826. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk) Almack's Assembly RoomsMuch has been written about Almack's Assembly Rooms elsewhere, I don't intend to duplicate that information here. For more social history related to Almack's, see Wikipedia, or one of the many blog posts about it. I will however review some of its influence on social dancing of the greater Regency era, and Paine's contributions. For a more general history of Almack's, see also the 1878 Old and New London: Volume 4.

I don't know the precise dates at which Paine led the orchestra at Almack's, but he published Quadrilles as

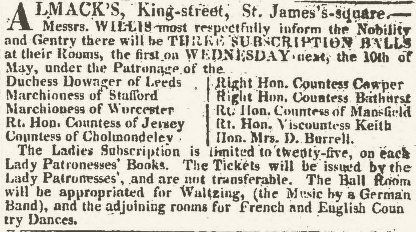

He may have had a formal position at Almack's, but he wasn't the only band leader to play there during this era. Captain Gronow reported in his 1862 Reminiscences that  Figure 5. An Almack's advert, The Morning Post, 6th May 1815.

Figure 5. An Almack's advert, The Morning Post, 6th May 1815. Image © THE BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Image reproduced with kind permission of The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

Almack's was an important venue, references to it could help to sell tune books. The covers of published dance collections began boasting that they were

The trend for crediting Almack's on the covers of dance publications accelerated during the Regency era. This was particularly true for Quadrille publications, almost all English Quadrille Sets of the 1810s and 1820s claimed to be It was not always so however, Almack's had to start somewhere. The anonymous author of the 1823 The Etiquette of the Ball-Room, and Delineation of the Art of Dancing Quadrilles, &c. by A Gentleman commented on an important element in the history of Almack's: It should be understood that Almack's, as it is called, is the Assembly from Hanover Square ... The subscribers, through dislike to Sir John Gallini, moved their Assembly, under the influence of the Countess of Salisbury, to King Street, St James', where the subscription has continued ever since in the name of "Almack's". Almack's hosted Balls for many of London's great dance masters. Examples include Gallini (The Public Advertiser, 9th March 1770), Delatre (Morning Chronicle and Daily Advertiser, 2nd March 1784), Noverre (The Public Advertiser, 2nd May, 1785) and Bishop (The World, 24th April, 1789). By the late 1820s Almack's was hosting the dance academy of the The Misses J. & S. Prince (The Morning Post, 7th December 1829), the Prince sisters were influential in popularising the Mazurka in London.  Figure 6. An Assembly Hall, perhaps Almack's. From the cover of the Brighton Almack Quadrilles, 1828. The musicians' gallery is elevated above the dance floor.

Figure 6. An Assembly Hall, perhaps Almack's. From the cover of the Brighton Almack Quadrilles, 1828. The musicians' gallery is elevated above the dance floor.

Almack's popularity meant that attendance had to be restricted. The owners found it convenient for attendees to subscribe for events through the Lady Patronesses, a cabal of noble ladies empowered to approve or reject such requests. The earliest reference to this I've found is from 1798 (True Briton, 23rd May 1798), but it may have begun much earlier. References to Lady Directresses at Almack's certainly go back further. It's possible that the institution of Patronesses was initially introduced to keep Sir John Gallini, and anyone like him, out. Whatever the origins, the exclusivity proved to be important, and competition for approval became intense. Much of fashionable society wanted to attend, but many were rejected by the patronesses. An 1815 advert in The Morning Post (19th May) clearly indicates the shortage of tickets: The list of patronesses from the above 1815 advert was: The Duchess Dowager of Leeds, Marchioness of Stafford, Marchioness of Worcester, Countess of Jersey, Countess of Cholmondeley, Countess Cowper, Countess Bathurst, Countess of Mansfield, Viscountess Keith, The Hon. Mrs. D. Burrell. The same list was published two weeks earlier (The Morning Post, 6th May 1815, see Figure 5), with the added detail that 25 tickets were available from each Patroness, giving a total of 250 tickets.

The list of patronesses could vary for each ball. One month earlier (The Morning Post, 10th April 1815) the patronesses for the preceding ball were listed as the Most Hon. Marchioness of Salisbury, the Right Hon. Countess of Cholmondeley, the Right Hon. Viscountess Castlereagh. I don't know the precise capacity of Almack's, but an 1817 report in The Morning Post (23rd June) mentions The rule that a ticket was required for entry was strictly enforced, but occasional exceptions could be made. An 1817 report in The Morning Chronicle (12th May) reveals: The rigorous rule of entry established at Almack's Rooms produced a curious incident at the last Ball. The Marquis and Marchioness of W--r, the Marchioness of T---, Lady Charlotte C---, and her daughter, had all been so imprudent as to come to the rooms without tickets; and though so intimately known to the Lady Managers and so perfectly unexceptionable, they were politely desired to withdraw, and accordingly they all submitted to the injunction; but the beautiful and interesting Miss C. was politely invited to remain as an exception to the rule, and she accordingly joined in the quadrilles with her usual elegance.

The anonymous author of the 1823 Etiquette of The Ball-Room by A Gentleman wrote against the poor state of Quadrille dancing in 1823 (he felt that British dancers were insufficiently graceful). He made an exception for the quality of dancing at Almack's: Another anonymous author published her Recollections of Almacks in 1863. She described the Almack's of the Regency era in gritty detail: Almack's had almost a venerable aspect of decay and of London dirt - a thing 'sui generis', when its lofty and lovely patronesses first swept across the floor. Their diamonds sparkled beneath the blaze of old-fashioned chandeliers: their dresses were contrasted with dusky walls and furniture. The main room was spacious nevertheless - lofty, and well adapted to the delicious sounds of Weippert's or Gow's band. It was not too large: you could see everyone, and be seen.  Figure 7. A chalked floor at Almack's, a detail from the covers of Paine's Quadrille Sets, from 1818.

Figure 7. A chalked floor at Almack's, a detail from the covers of Paine's Quadrille Sets, from 1818.Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.798 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

New dances came to England from Europe throughout the greater Regency era. Cotillions were danced at Almack's from 1770 (The Public Advertiser, 24th February), Quadrilles from around 1815, and Waltzes perhaps a little earlier. The Scottish style of Medley Dance was pioneered at Almack's in the 1780s, it was a collection of Country Dancing tunes adapted to the same set of dancing figures; it presumably relieved the tedium of the same tune being played for 20 or more minutes (The Caledonian Medley Dance, Skillern, c.1787). After a new dance debuted at Almack's it would go on to be danced elsewhere in England by the dancing elite. This is most clear in reference to the Quadrille, but might also apply to the Waltz, Gallopades and Mazurkas. The author of Recollections of Almack's ended her essay recording perhaps the last major dancing revolution:

It's likely that Paine helped to popularise the Waltz at Almack's. The Waltz was a controversial dance form during the first half of the 1810s, too intimate for respectable dancers. There are several references in the contemporary press of Waltzes being danced at Almack's in 1815; for example, an 1815 advert for Almack's in The Morning Post (6th May, see Figure 5) reports

Paine emphasised his role at Almack's by using an image of their floor on the cover of his 1818 9th Quadrille Set (see Figure 7, small text under the final image read

As leader of the Orchestra during the mid to late 1810s, Paine was well placed to trade on his position. He published Quadrille music and was uniquely able to claim that they were Paine's First SetWe've previously investigated the origins of the First Set of Quadrilles and the role of Edward Payne in publishing Payne's First Set (probably) in 1815. This time we'll investigate Paine's First Set. You can learn more about dancing them here (and see the copy I've shared here).

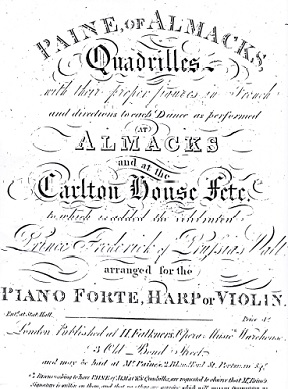

It was recorded, once again by Captain Gronow, that Lady Jersey introduced the first Quadrille Set to Almack's in 1815. It's likely that Paine would have led the orchestra on this inaugural occasion. James Paine never claimed that he was the inventor of the Quadrilles, he did however publish the accredited version  Figure 8. Paine's First Set, 1816

Figure 8. Paine's First Set, 1816Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.798 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

I have no reason to doubt that Edward Payne's First Set was published before that of James Paine's, just as Edward Payne claimed. Paine advertised his publication as The figures used in these dances are understood to have originated in France, perhaps arriving by way of Brussels. Many early British quadrilles were themed around the 1815 Battle of Waterloo, they are thought to have been danced by the British officers in Belgium and France. It's likely that this specific arrangement of Figures were danced at the Regent's Fete at Carlton House in July 1816.

G.M.S. Chivers reported in his 1824 Quadrille Preceptor that the figures of Paine's First Set were always As an aside, it's fairly easy to find British Quadrille Sets that use this terminology and have been dated prior to 1816. Such documents almost never print a date on their covers however, archivists have estimated the dates of publication. It's not uncommon, in my experience, for estimated dates to be inaccurate by as much as 10 years (sometimes more) when verified against their copyright registrations, etc.. Be wary of all uncorroborated dates, including mine! The figure sequences of the First Set originated in France. They appear in several French collections of unconfirmed date. One notable example are the Quadrilles of Louis-Julien Clarchies, many of which were published in London by Clementi & Co. in 1810 and 1811. Clarchies died in 1815, his Quadrilles almost certainly date earlier than either Paine's or Payne's First Set publications. Clarchies used the names Pantalon, etc., he may have been Edward Payne's direct source for his First Set. Paine's figure sequences became supremely popular in England (regardless of their immediate origin); this may have influenced their use in France where they evolved from being one amongst many such Quadrille arrangements to become the standard arrangement. It's perhaps noteworthy that one of the more significant of the early Quadrille dancing publications was sold through Reibau's Library (i.e. Paine's father-in-law's business) at 2 Blandford-street in 1818 (Morning Post, 1st June, 1818). This was the anonymously published Le Maitre a Danser by an unnamed French dancing master. Several editions of this work were published, including the 1820 third edition (Morning Post, 4th April, 1820). It's possible that Paine worked with this anonymous dancing master. The anonymous author of Recollections of Almacks wrote of the introduction of Quadrille dancing, and of Paine's First Set: This fascinating recollection goes into far more detail than I can reasonably quote here. But it ably demonstrates the practical difficulties of introducing a new dance form.Quadrilles had struggled into existence ere Almack's became Almack's; they were, at first, regarded as a heresy...

Despite the mysteries of their origin, James Paine was widely credited as having invented the First Set in the following decades. As early as c.1818 Joseph Hart described the First Set figures as

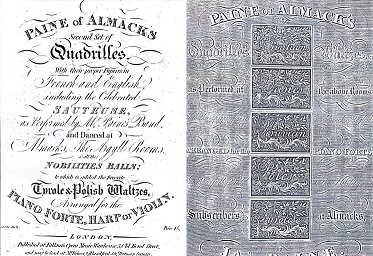

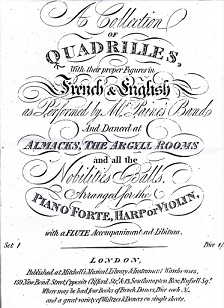

Paine's QuadrillesPaine published at least 17 numbered Sets of Quadrilles between 1816 and 1821. Many of them were advertised in newspapers, which provides a convenient and accurate mechanism for dating them. I've found advertisements and other references that date his Quadrilles as follows:  Figure 9. Paine's Second (1816) and Ninth (1818) Sets

Figure 9. Paine's Second (1816) and Ninth (1818) SetsImage © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.798 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Paine also published an additional unnumbered Quadrille Set in 1826, it was based on Rossini's opera Semiramide (see Figure 4). He intended this to be the start of a new series, a follow-up was advertised in The Harmonicon in 1827. We know that his Semiramide Quadrilles were danced as they're explicitly mentioned in the 1826 report of Viscountess Hampden's Ball (see Figure 3). Joseph Hart's 19th Set of Quadrilles, also based on Semiramide, had been published one year earlier in 1825. Rossini was proving to be popular with the Quadrille buying public of the 1820s, Hart alone published 8 Sets of Quadrilles based on Rossini's operas. Each of Paine's Quadrille Sets introduced a new collection of music, the dancing figures remained quite similar however. His first 3 Sets were each made up of 6 separate Quadrille dances, the remainder only had 5 (the same length that most other choreographers provided at around this date). Each Set was accompanied by one or more instrumental tunes, generally Waltzes, occasionally a Polonaise or Sauteuse. The figures themselves remain almost the same across each Quadrille Set, with minor variations introduced for the 4th or 5th Quadrille in each Set. Paine was a musician rather than a dancing master, this might explain why he left the figures relatively unchanged; the evidence of Paine's 1817 Quadrille Fan (of which we'll read more in a moment) suggests that the dancers at Almack's avoided variety in their Quadrille dances at that early date. Paine's reuse of the same figures in many of his Quadrilles helped to promote the First Set as the standard Quadrille dancing arrangement in London (and therefore England) into perpetuity. As with many other early Quadrilles, the figures of Paine's Quadrille Sets were often sold as miniature cards, suitable for carrying in a reticule, an example of which can be seen in Figure 11. Thomas Wilson, in his 1820/1824 epic poem The Danciad, offered a mixed review of Paine's Quadrilles. He wrote the following:  Figure 10. Quadrilles

Figure 10. Quadrilles as Performed by Mr. Paine's Band, published by Mitchell's Musical Library, c.1816 Image © BRITISH LIBRARY BOARD, h.925.c.(7.) ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OfWilson appears to have confirmed that Paine published his Quadrilles after the First Set had already become established. Elsewhere in The Danciad he explained that the First Set didn't originally include La Pastorale, it came to be added later (presumably under the influence of Paine himself).Paine's, of Almacks,sixteen sets I'm told,

G.M.S. Chivers' 1824 Quadrille Preceptor included the figures for 10 Sets of Quadrilles he described as

In 1817 Paine advertised a

Paine is also credited with publishing a work called Paine's Terpsichorean Preceptor, or, Handbook for the Ball Room, a copy of which exists in the Harvard Theatre Collection. It's said to be a miniature work, and contained the figures for a number of popular Quadrille Sets  Figure 11. An example of Paine of Almack's Quadrilles as miniature cards

Figure 11. An example of Paine of Almack's Quadrilles as miniature cards (Image from eBay) Paine published almost exclusively through Falkner's Opera Music Warehouse, at least until 1821. He suffered the same copyright problems that we previously discovered with Edward Payne, unofficial copies of his Quadrilles were printed and sold by other publishers. Some editions of his second and subsequent Quadrille Sets included a written notification as follows: This may be a reference to the Quadrilles published by Mitchell's Musical Library & Instrument Warehouses (see Figure 10) which featured the same wording that Paine complained about, and offered a different (arguably superior) arrangement of the music; it may also be a reference to the similar Quadrilles sold by Skillern & Challoner from 1816, or by Chappell & Co. probably from the start of 1817. Paine took the same remedial action as many of his contemporaries, he personally signed every official copy of his Quadrilles.Mr Paine feels it an incumbent duty he owes the Public and himself, to prevent further imposition...to caution them against a spurious Edition of Quadrilles, which has been published, the Title of them expressing to have been performed by Paine's Band, which is a gross imposition, as many of them never were performed by him; and the Accompaniments to them are very different to the original, which completely alters the Airs, and spoils the effect. Ultimately Paine was successful in promoting his Quadrille arrangements over those of Edward Payne. Payne died in 1819 leaving Paine to accept sole credit for the success of the Quadrilles that they (and others) had both popularised. The Quadrille dancing public, with the passage of time, almost completely forgot Edward Payne's role in their origins. The following table lists Paine's Quadrilles, mostly as documented at the British Library. The Library doesn't have all copies of all of Paine's Quadrilles, there are some gaps in the table.

Paine's Music Shop

At some point Paine opened a music shop at 92 High-street, Marylebone. He lived at this address for several years (see Figure 4), though he eventually bought a separate residence just down the road at 19 High-street. His shop certainly existed in 1824, though he may have opened the store earlier. Paine described himself as both a I've not found many references to his music shop, though it was mentioned in at least two different legal proceedings. The Morning Chronicle (17th December 1824) reported on the trial of a violin thief who stole from Paine's store. The guilty party was ordered to return the instrument, and Paine was granted permission to prosecute for swindling. In 1847 Paine's house was burgled, the details of the case are available online, they mention the existence of Paine's shop. This later case involved testimony from two of Paine's children, James Henry Paine and Caroline Riebau Paine.

A similarly named but (as far as I can tell) unrelated music shop was that of Paine & Hopkirk. This firm opened c.1821, and was dissolved in 1836. Frank Kidson in his 1900 British Music Publishers, Printers and Engravers speculated that James Paine may have been a partner in this business. He wasn't, it was actually a John Edward Paine who died in 1846. John Paine also published a collection of Country Dances in 1807, and a further dance collection c.1815. I've not established a connection between John and James Paine, though they may have been related. This firm has an unusual claim to fame - it provided the first postal address in 1834 for the Universal Life Assurance Society, a company that eventually became Aviva.

James Paine disappeared into obscurity by the end of the 1820s. He died in 1855 a relatively wealthy man, his name remained associated with his Quadrille dances for the rest of the 19th century. But that's where my research into Paine's life ends. As usual, there are many gaps in the story; if you can provide any further details or access to some of his published works, please do get in touch.

|

Copyright © RegencyDances.org 2010-2024

All Rights Reserved